Banten Sultanate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sultanate of Banten

ᮊᮞᮥᮜ᮪ᮒᮔᮔ᮪ ᮘᮔ᮪ᮒᮨᮔ᮪

كسلطانن بنتن Kasultanan Banten |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1526–1813 | |||||||||||||||||

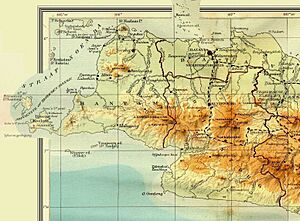

Rough extent of Banten at the death of Hasanudin, controlling both sides of Sunda Strait

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Status |

|

||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Old Banten, Serang | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||

|

• 1552–1570

|

Sultan Maulana Hasanuddin | ||||||||||||||||

|

• 1651–1683

|

Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa | ||||||||||||||||

|

• 1809–1813

|

Sultan Maulana Muhammad Shafiuddin | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

|

• Syarif Hidayatullah conquered Banten

|

1526 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Conquest of the Sunda Kingdom

|

1527 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Independence from Cirebon Sultanate

|

1552 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Fall of Jayakarta

|

1619 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Client state of VOC

|

1683 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Annexed by the French Empire

|

1808 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Annexed by the Dutch East Indies

|

1813 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia | ||||||||||||||||

The Banten Sultanate was a powerful Islamic kingdom in Southeast Asia. It was founded in the 16th century on the northwest coast of Java, in a port city called Banten. This city was also known as Bantam by Europeans.

The Sultanate was a major trading hub, especially for pepper. It was at its strongest in the late 1500s and mid-1600s. However, it later faced challenges from the Dutch. The Dutch eventually took control, and Banten became part of the Dutch East Indies in 1813.

Today, the area where the Sultanate once stood is the Indonesian province of Banten. The Great Mosque of Banten in Old Banten is still a popular place for visitors and pilgrims.

Contents

How Banten Started

Before 1526, there was a town called Banten about ten kilometers inland. It was known as Banten Girang, meaning "Upper Banten." This town was part of the Hindu Kingdom of Sunda.

A Muslim scholar named Sunan Gunungjati arrived in Banten Girang in the early 1500s. He wanted to spread Islam in the area. Gunungjati was also a leader of the Sultanate of Cirebon. In 1482, Cirebon declared its independence from the Sunda Kingdom.

The Portuguese, a European power, made an alliance with the Hindu Sunda Kingdom in 1522. When Gunungjati learned about this, he asked the Demak Sultanate for help. His son, Hasanudin, likely led the military action in 1527. They defeated the Portuguese fleet that wanted to build a fort.

Gunungjati and Hasanudin took control of Banten and another port called Kelapa. The King of Sunda could not stop them. Hasanudin was then made the leader of Banten by the Sultan of Demak. This marked the start of the new Banten Sultanate. Its capital was Old Banten, which is now part of Serang.

Banten Grows Stronger

Hasanuddin's Early Rule

Sultan Hasanuddin wanted Banten to become a rich trading center again. He focused on the spice trade, especially pepper. He traveled to southern Sumatra (today Lampung province) to secure pepper supplies. This spice was key to Banten's international trade and wealth.

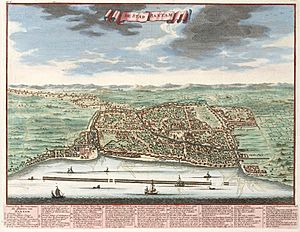

Hasanuddin decided to build a new capital city on the coast. It was located at the mouth of the Cibanten River. The city was well-planned with main streets and separate areas for the royal palace, mosque, and merchant quarters. Foreign traders lived outside the royal city.

In 1546, Hasanuddin joined a military trip with the Sultan of Demak. The Demak Sultan died during this trip. Hasanuddin used this chance to make Banten fully independent from Demak.

From the 1550s, Banten became very prosperous. Trade with Portuguese Malacca, a former rival, grew. Hasanuddin's son, Maulana Yusuf, helped manage the kingdom's development.

The city's population grew quickly. Large farming projects were started with new irrigation canals and rice fields. The capital city was also protected by strong brick walls, 8 kilometers long and 1.8 meters thick. Maulana Yusuf also oversaw the building of the Great Mosque of Banten.

During this time, Hasanuddin decided to conquer the remaining parts of the Kingdom of Sunda. Maulana Yusuf led the attack on its capital, Dayeuh Pakuan (modern Bogor). The Sunda Kingdom was already weak and offered little resistance. Banten then controlled all of Sunda west of the Citarum River.

A sacred stone, which was the throne of the Sunda Kingdom, was moved to Banten's royal square. This showed the end of the Sundanese dynasty and the rise of Banten.

When Hasanuddin died in 1570, Banten controlled all of Sunda (except Cirebon and Sumedang Larang) and southern Sumatra. It had become one of the largest trading centers in Southeast Asia.

Maulana Yusuf and a Succession Challenge

After Hasanuddin's death in 1570, his son, Maulana Yusuf, became Sultan. He was an experienced ruler, having worked alongside his father.

Yusuf chose his young son, Prince Muhammad, as his heir. However, Yusuf became ill and died in 1580. Prince Muhammad was only nine years old. This caused a problem, as Yusuf's younger brother, Pangeran Japara, wanted to become king.

The court was divided. Some supported Pangeran Japara, while others, especially the religious leader (qadi), wanted to protect the young prince's right to the throne. A conflict almost broke out, but it was avoided when the Prime Minister changed his mind and supported Prince Muhammad.

Historians believe this showed a struggle between different groups in Banten. Some wanted more economic freedom, while others wanted stronger government control. The young prince's rule meant more freedom for merchants.

Muhammad and the Palembang Campaign

Prince Muhammad became Sultan in 1580 when he was nine. During his rule, Banten continued to thrive. Merchants enjoyed freedom in trade, and pepper remained the main export. Many traders from across Asia came to Banten, bringing wealth to the kingdom.

Feeling powerful, the 25-year-old Sultan Muhammad launched a military campaign in 1596. He attacked the principality of Palembang in southern Sumatra. Palembang was not yet an Islamic state, and Muhammad wanted to expand his kingdom, just like his father and grandfather had.

However, during the siege of Palembang, a cannonball hit and killed Sultan Muhammad on his ship. With the king's sudden death, Banten's expansion plans stopped, and the troops returned home.

European Traders Arrive

A few months after Sultan Muhammad's death, European trading ships arrived in Banten. On June 27, 1596, the first Dutch fleet, led by Cornelis de Houtman, landed. This voyage was profitable for the Dutch.

In 1600, the Dutch formed the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC). Their goal was to control the spice trade. Unlike the Portuguese, who had blended into the Asian trade system, the Dutch wanted to take over the trade completely. The Portuguese and Dutch fought fiercely for influence in Banten. In 1601, the Portuguese fleet was defeated in a naval battle.

Other Europeans followed. The English set up a trading post in Banten in 1602. In 1603, the Dutch also established their first permanent trading post in Indonesia in Banten.

With a child king and no strong leader, a council governed Banten. The expulsion of the Portuguese led to the Dutch and English competing for control. This caused a civil war in Banten in 1602. Peace was restored in 1609 when Prince Ranamanggala became the new regent.

Ranamanggala tried to regain state control over trade. He imposed taxes and set prices. He also sent many merchants to Jayakarta (a port to the east), reducing their power. This strong policy did not please the Dutch and English. A few years later, they moved their trading posts to Jayakarta.

Banten's Decline

Jayakarta Becomes Dutch Batavia

In 1619, the Dutch East India Company's Governor-General, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, attacked and burned Jayakarta. He built a new fortified city called Batavia (now Jakarta) on its ruins. Batavia became the center of Dutch operations and a major rival to Banten.

Coen wanted to control all trade by creating a monopoly. He blockaded Banten's harbor for about 15 years. Banten responded by stopping all pepper exports to Batavia. However, the Dutch blockade hurt Banten's trade, as many Asian merchants, especially Chinese, could not reach the port. This caused a large amount of unsold pepper to pile up.

The crisis was severe. Prince Ranamanggala decided that the Europeans were the cause of the problems. In a desperate move, he ordered all pepper plants in the region to be destroyed. This policy was a disaster for merchants. They pressured the court, leading to Ranamanggala's resignation in 1624. The young Sultan Abulmufakhir, now 28, took over.

Abu al-Mafakhir's Reign and New Challenges

Sultan Abu al-Mufakhir Mahmud Abdulkadir's reign was marked by complex relations with Batavia and the Mataram Sultanate. In 1628, the English returned to Banten, helping its trade against the Dutch.

The Mataram Sultanate grew powerful in Java and attacked Batavia in 1628 and 1629. During this time, Banten lost some of its territories, Pajajaran and Priangan, to Mataram. Banten and Batavia, fearing Mataram, improved their relations. Mataram failed to capture Batavia and later weakened due to internal conflicts.

Between 1629 and 1631, Banten started major farming projects. They dug canals and built dams to grow rice and a new export crop: sugar. Chinese merchants in Kelapadua village established possibly the first sugar plantation in Java.

In 1635, Sultan Abu al-Mafakhir made his son, Prince Pekik, his co-ruler. A peace treaty with Batavia was signed in 1639. In 1636, Banten sent an envoy to Mecca for the first time. Two years later, the king received the respected title of "sultan" from the Grand Shareef of Mecca. This was the first time a Javanese king received this title.

The peace treaty meant Banten had to recognize Batavia and stop trading with the Moluccas. In return, Batavia lifted its blockade and promised neutrality if Mataram attacked Banten.

Sultan Abu al-Mafakhir allowed merchants to trade directly with Banten's colonies in Sumatra. This led to some rebellions in places like Bengkulu and Lampung, but Banten's forces crushed them.

The Dutch captured Malacca in 1641, scattering Portuguese merchants. Some came to Makassar, helping its trade. Banten also started trading with the Spanish in Manila for silver from South America.

The 1640s were peaceful for Banten. Small boats from Banten supplied Batavia with farm products. The English and Danish also traded in Banten, bringing Indian fabrics. Banten regained its status as an important trading center. It established diplomatic ties with many kingdoms, from Palembang to Japan.

Banten used its wealth to buy weapons and train soldiers. In 1644, Mataram proposed an alliance, but Banten refused. Banten then set its sights on Cirebon, which was a vassal of Mataram. Banten believed Cirebon belonged in its sphere of influence.

In 1650, Mataram demanded Banten submit to its rule. Banten refused, saying it only honored the Grand Shareef of Mecca. Mataram sent a fleet to invade Banten. In the Pagarage War of 1650, Banten's navy defeated the Cirebon-Mataram forces.

In 1650, Sultan Abu al-Mafakhir's son and co-ruler, Abu al-Ma'ali, died. Ma'ali's son, Prince Surya, was chosen as the next successor. In 1651, the old Sultan Abu al-Mufakhir died. Prince Surya, at 25, became the sole ruler, known as Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa.

Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa: The Last Golden Age

Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa inherited a strong and respected kingdom. He appointed his friend Kyai Mangunjaya as Prime Minister. Banten and Mataram continued their rivalry. Mataram tried to gain influence over Cirebon, but Sultan Ageng declined a marriage proposal that would have made his daughter a hostage.

The Anglo-Dutch Wars in Europe affected trade in Banten. The Dutch in Batavia again blockaded Banten, as it was a center for British trade. Banten, though not as powerful as the Dutch, resisted. It used guerrilla tactics, attacking Dutch ships and raiding farms around Batavia.

In 1656, Chinese merchants helped broker peace talks between Banten and Batavia. A treaty was signed in 1659.

Starting in 1653, Sultan Ageng began major farming reforms. He cleared thousands of acres of land near Batavia and planted coconut trees. He also started a huge irrigation project between 1663 and 1677. This involved digging 40 kilometers of canals and building dams. Over 40,000 hectares of land became rice fields, and 30,000 people were resettled. In 1678, Sultan Ageng built a new palace in Tirtayasa village. The name Tirtayasa means "water management," showing the Sultan's pride in this project. This led to his famous nickname, Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa.

By the 1660s, Banten expanded its rule to Landak in Western Borneo. Sultan Ageng also appointed a Chinese man named Kaytsu as his foreign trade minister. Kaytsu helped Banten build its own fleet of trading ships, modeled after European designs. Banten's ships began trading directly with many places, including China, Japan, India, and even London.

Banten's free trade policy attracted many nations. By 1670, Danish, French, Portuguese, and Chinese traders joined the English and Dutch in Banten. Indian traders also returned, selling their fabrics.

Banten's economy prospered, and its political influence grew. It exchanged letters with rulers from England, Denmark, France, and various Asian countries. Diplomatic missions were sent to England and Arabia. The Sultan's son even went on a pilgrimage to Mecca on Banten's own ship.

Banten also became involved in Cirebon's politics. Cirebon was a vassal of Mataram, but its relations were tense. Sultan Ageng helped free Cirebon princes who were held hostage by Mataram. He then crowned them as separate sultans, weakening Cirebon and preventing it from allying with Mataram.

However, Batavia did not want Banten to become too powerful. The Dutch allied with Mataram and fought Banten for two years. Banten lost control of Cirebon. Defeated, Sultan Ageng retreated from government, leaving his son, Sultan Haji, in charge.

Civil War: Father vs. Son

A conflict broke out between Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa and his son, Sultan Haji. Sultan Ageng wanted free trade with all European powers. But Sultan Haji wanted closer ties with the Dutch in Batavia.

Sultan Haji, upset by criticism from his father's loyal officials, demanded the removal of Prime Minister Mangunjaya. Sultan Ageng agreed to exile his friend to avoid conflict. However, Mangunjaya was murdered weeks later.

In 1682, angered by his friend's death, Sultan Ageng returned to Banten. He stormed the palace to take back power from his son. Sultan Haji retreated to a fortress he had built inside the palace. He sent a message to Batavia, asking the Dutch for help.

The Dutch were happy to see trouble in Banten. They quickly sent their fleet to rescue Sultan Haji. Sultan Haji was freed, while his father and loyal men retreated to the countryside to continue their fight. A civil war lasted for several years.

With Sultan Haji allied with the VOC, a war broke out between Batavia and Banten in the 1680s. Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa was eventually forced to surrender. He was imprisoned in Banten and later in Batavia, where he died in 1692.

In return for their help, the Dutch made Sultan Haji sign harsh agreements. All foreigners had to leave Banten, the Dutch gained a monopoly on pepper trade, and they could establish a military base in Banten. The Dutch also tore down Banten's fortifications and built Fort Speelwijk at the port entrance.

The civil war and Dutch involvement were disastrous for Banten. The VOC gained control of Bogor and the Priangan Highlands. Banten's power was greatly reduced, making it a protectorate of the VOC. It was still independent in name, but its true power was gone.

In the following years, Banten was forced to follow Batavia's orders. Its influence overseas also declined. In 1752, the Dutch took over Banten's territories in western Borneo and southern Sumatra.

The End of Banten

After Sultan Haji's reign in the late 1600s, Banten lost most of its power to the Dutch. Although the Sultanate continued through the 1700s, it was a shadow of its former glory. The nearby port city of Batavia had overshadowed it.

In 1800, the Dutch East India Company went bankrupt. Its possessions became a Dutch colony, the Dutch East Indies. In 1808, Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels ordered Sultan Aliyuddin II of Banten to move his capital and provide workers for a new port. The Sultan refused.

Daendels invaded Banten and destroyed the Surosowan palace. The Sultan and his family were arrested and exiled. On November 22, 1808, Daendels declared that the Banten Sultanate was now part of the Dutch East Indies.

Finally, in 1813, the Banten Sultanate officially ended. Thomas Stamford Raffles, a British leader, forced Sultan Muhamad Syafiuddin to give up his throne. This marked the complete end of the Banten Sultanate.

Economy of Banten

Banten's economy was mostly based on pepper. This spice was its most important product for international trade. Even in the 13th century, Chinese records mentioned that the area around the Sunda Strait, including Banten, was famous for its excellent pepper. The Muslim Banten Sultanate simply took over the pepper trade that the earlier Hindu Sunda Kingdom had established.

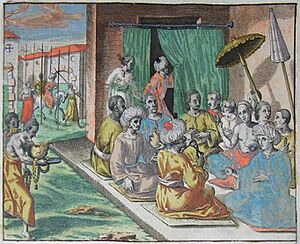

Pepper was what attracted foreign traders to Banten. Merchants from China, India, Turkey, Portugal, the Netherlands, England, and Denmark all came to Banten's harbor. They traded spices, silk, Chinese ceramics, gold, jewelry, and other Asian goods. Banten was a leader in international trade.

Danish merchants from Tranquebar also came to Banten for pepper. Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa even wrote letters to Frederick III of Denmark, offering to trade pepper for firearms and gunpowder.

Religion in Banten

The desire to spread Islam was a key reason why the Demak Sultanate captured Banten in 1527. They replaced the Hindu Sunda Kingdom with an Islamic one. Another reason was to prevent the Catholic Christian Portuguese from building a base in Java. Muslim preachers also played a big role in spreading Islam in Indonesia in the 15th century. Islam was also the main religion of Asian merchants, who created trade networks from Arabia to Indonesia.

However, the spread of Islam in Western Java was not always peaceful. Banten Girang, Kalapa, and Pajajaran were taken by military force. Sundanese prisoners were sometimes spared if they converted to Islam.

Despite this, the kings of Banten showed tolerance. They did not force the native Baduy people to convert to Islam. These former Sundanese subjects were allowed to keep their old faith and way of life. The Banten kings even had a bodyguard unit made up of these non-Muslim "highlanders." They also allowed Chinese temples and Christian churches to be built for merchants.

Banten was also a famous center for Islamic studies. Islam was a very important part of Bantenese life. Islamic ceremonies and customs were celebrated with great importance. After the Sultan, the qadi (religious judge) held a powerful position in the court. Many Islamic scholars from India and Arabia were invited to Banten to share their knowledge. Religious schools called pesantren were set up, with the Kasunyatan pesantren being one of the most respected.

One famous Islamic scholar in Banten was Sheikh Yusuf from Makassar. Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa also sent Banten's first ocean-going ship to Jeddah so his son could go on a pilgrimage to Mecca. This made Sultan Haji the first ruler in the archipelago to complete the hajj pilgrimage. These actions showed Banten's important place within the larger Islamic community.

By the 19th century, many Indonesian scholars who studied and taught in Mecca were from Banten. One example is Sheikh Nawawi al-Bantani, who became a professor and imam of the Great Mosque of Mecca. This religious prestige made Banten, along with Aceh, one of the most important Islamic kingdoms in the archipelago.

Culture of Banten

Banten was known in Europe as a prosperous country. For example, in a play by Henry Fielding, a character becomes "The Prince of Bantam," showing how people in London saw Banten as a place of great fortune.

Religious tolerance was well-developed in Banten. Even though most people were Muslim, other communities were allowed to build their places of worship. By 1673, several temples had been built near Banten's port.

Around 1676, thousands of Chinese people came to Banten seeking safety and work. This happened because of wars in Fujian and other parts of South China. These communities usually settled near the coasts and rivers. There were also many Indian and Arab communities. European groups like the British, Dutch, French, Danish, and Portuguese also built homes and warehouses near the Ci Banten River.

List of Sultans of Banten

- Syarif Hidayatullah or Sunan Gunung Jati from Sultanate of Cirebon

- Sultan Maulana Hasanuddin or Prince Sabakinking 1552 – 1570

- Sultan Maulana Yusuf or Prince Pasareyan 1570 – 1585

- Sultan Maulana Muhammad or Prince Sedangrana 1585 – 1596

- Sultan Abu al-Mafakhir Mahmud Abdulkadir or Pangeran Ratu 1596 – 1647

- Sultan Abu al-Ma'ali Ahmad 1647 – 1651

- Sultan Abu al-Fath Abdul Fattah or Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa 1651 – 1683

- Sultan Abu Nashar Abdul Qahar or Sultan Haji 1683 – 1687

- Sultan Abu Fadhl Muhammad Yahya 1687 – 1690

- Sultan Abu al-Mahasin Muhammad Zainul Abidin 1690 – 1733

- Sultan Abu al-Fathi Muhammad Syifa Zainul Arifin 1733 – 1750

- Sultan Syarifuddin Ratu Wakil, in effect Ratu Syarifah Fatimah 1750 – 1752

- Sultan Abu al-Ma'ali Muhammad Wasi Zainal Alimin or Pangeran Arya Adisantika 1752 – 1753

- Sultan Arif Zainul Asyiqin al-Qadiri 1753 – 1773

- Sultan Abu al-Mafakhir Muhammad Aliuddin 1773 – 1799

- Sultan Abu al-Fath Muhammad Muhyiddin Zainussalihin 1799 – 1801

- Sultan Abu al-Nashar Muhammad Ishaq Zainulmutaqin 1801 – 1802

- Caretaker Sultan Wakil Pangeran Natawijaya 1802 – 1803

- Sultan Abu al-Mafakhir Muhammad Aliyuddin II 1803 – 1808

- Caretaker Sultan Wakil Pangeran Suramenggala 1808 – 1809

- Sultan Muhammad ibn Muhammad Muhyiddin Zainussalihin 1809 – 1813

See also

- History of Indonesia

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- List of monarchs of Java

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |