Portuguese Malacca facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Portuguese Malacca

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1511–1641 | |||||||||

Malacca, shown within modern Malaysia

|

|||||||||

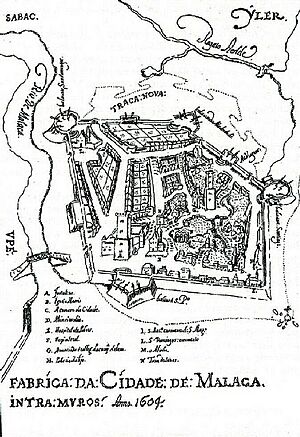

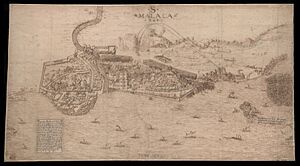

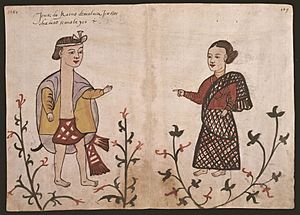

Portuguese Malacca in Lendas da India by Gaspar Correia, ca. 1550–1563.

|

|||||||||

| Status | Portuguese colony | ||||||||

| Capital | Malacca Town | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| King of Portugal | |||||||||

|

• 1511–1521

|

Manuel I | ||||||||

|

• 1640–1641

|

John IV | ||||||||

| Captains-major | |||||||||

|

• 1512–1514 (first)

|

Rui de Brito Patalim | ||||||||

|

• 1638–1641 (last)

|

Manuel de Sousa Coutinho | ||||||||

| Captains-general | |||||||||

|

• 1616–1635 (first)

|

António Pinto da Fonseca | ||||||||

|

• 1637–1641 (last)

|

Luís Martins de Sousa Chichorro | ||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Imperialism | ||||||||

|

• Captured

|

15 August 1511 | ||||||||

|

• Dutch conquest

|

14 January 1641 | ||||||||

| Currency | Portuguese real | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

Malacca was a city on the Malay Peninsula that was controlled by the Portuguese Empire for 130 years. This period lasted from 1511 to 1641. The Portuguese took Malacca from the Malacca Sultanate. They wanted to control the important trade routes in the area. Even though the Malacca Sultanate tried many times to get their city back, they failed. Eventually, the city was lost to an alliance of Dutch and local forces. This led to a period of Dutch rule in Malacca.

Contents

History of Portuguese Malacca

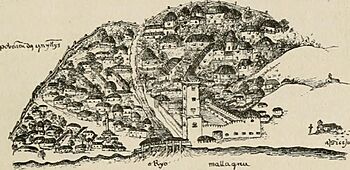

According to a historian named Emanuel Godinho de Erédia, the old city of Malacca was named after the malacca tree. These trees grew along a river called Airlele. The Airlele river started from a place called Buquet China, which is now Bukit Cina. Erédia said that the first King of Malacca, Permicuri (also known as Parameswara), founded the city in 1411.

How Malacca Was Captured

Malacca was very rich, and its wealth caught the eye of King Manuel I of Portugal. He sent a captain named Diogo Lopes de Sequeira to Malacca in 1509. Sequeira was the first European to reach Southeast Asia. His goal was to make a trade agreement with the ruler of Malacca.

At first, Sultan Mahmud Shah welcomed Sequeira. However, problems soon started. Some Muslims in the sultan's court stirred up feelings of rivalry between Islam and Christianity. Muslim traders from other countries convinced Sultan Mahmud that the Portuguese were a danger. Because of this, Sultan Mahmud attacked the four Portuguese ships in the harbor. Some Portuguese sailors were killed, and others were captured, imprisoned, and tortured. The Portuguese realized that they would have to conquer Malacca to establish themselves there, just as they had done in India.

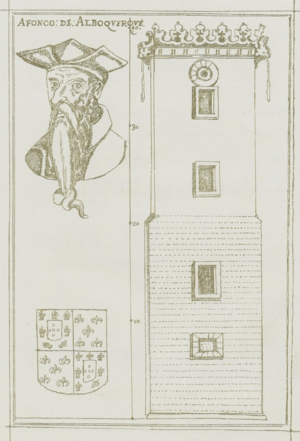

In April 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque sailed from Goa to Malacca. He had about 1,200 men and 17 or 18 ships. Albuquerque made several demands. One demand was to build a fortress near the city for safe trading. The sultan refused. After 40 days of fighting, Malacca fell to the Portuguese on August 24. Sultan Mahmud Shah fled the city. A disagreement between Sultan Mahmud and his son, Sultan Ahmad, also weakened the Malaccan side.

After defeating the Malacca Sultanate, Afonso de Albuquerque built a fort. He expected counterattacks from Sultan Mahmud. The fortress was designed and built near a hill, south of the river mouth, where a mosque used to be. Albuquerque stayed in Malacca until November 1511. He worked on strengthening its defenses against any Malay attacks.

A Portuguese Port in a Difficult Region

Portuguese Malacca faced many challenges. It was the first European Christian trading settlement in Southeast Asia. It was surrounded by many new Muslim states. These states were hostile and wanted to remove the Portuguese and take back the port town.

Sultan Mahmud tried many times to recapture Malacca. He got help from his ally, the Sultanate of Demak in Java. In 1511, they sent naval forces to help. These combined Malay and Java forces were led by Pati Unus, the Sultan of Demak, but they failed. The Portuguese fought back and forced the sultan to flee to Pahang. Later, the sultan sailed to Bintan Island and set up a new capital there.

From his new base, the sultan gathered his scattered Malay forces. He organized several attacks and blockades against the Portuguese. These frequent raids on Malacca caused great hardship for the Portuguese. In 1521, the Sultanate of Demak launched a second campaign to help the Malay sultan retake Malacca. This also failed, and the Sultan of Demak died. He was later known as Pangeran Sabrang Lor, meaning the Prince who crossed the Java Sea to the North.

The raids convinced the Portuguese that they needed to stop the exiled sultan's forces. They made several attempts to defeat the Malay forces. Finally, in 1526, the Portuguese completely destroyed Bintan. The sultan then went to Kampar in Riau, Sumatra. He died there two years later. He had two sons, Muzaffar Shah and Alauddin Riayat Shah II.

Muzaffar Shah was asked by people in the north to be their ruler. He then started the Sultanate of Perak. Mahmud's other son, Alauddin, became the new ruler. He created a new capital in the south, forming the Johor Sultanate.

The Sultan of Johor tried several times to end Portuguese rule in Malacca. In 1550, he asked Java for help. Ratu Kalinyamat, the queen of Jepara, sent 4,000 soldiers on 40 ships to help Johor take Malacca. The Jepara troops joined the Malay alliance. They gathered about 200 warships for the attack. The combined forces attacked from the north and captured most of Malacca. However, the Portuguese fought back and pushed the invaders away. The Malay alliance troops were forced back to the sea. The Jepara troops stayed on shore but left after their leaders were killed. The battle continued on the beach and in the sea. More than 2,000 Jepara soldiers were killed. A storm left two Jepara ships stuck on the shore of Malacca, where the Portuguese attacked them. Fewer than half of the Jepara soldiers managed to leave Malacca.

In 1568, Prince Husain Ali I Riayat Syah from the Sultanate of Aceh launched a naval attack to remove the Portuguese from Malacca, but it failed. In 1574, a combined attack from the Aceh Sultanate and Javanese Jepara tried again to capture Malacca. This also failed because they did not work together well.

Other ports, like Johor, started to compete with Malacca. Asian traders began to avoid Malacca, and the city's importance as a trading port declined. Instead of controlling trade, the Portuguese had actually messed up the Asian trade network. Malacca was no longer the main trading hub. Trade became spread out among many ports, which often fought with each other.

China's Reaction

Malacca had a group of Chinese merchants, likely from Fujian. They had left China against Ming laws. The sultan probably did not treat them well. Almost all of them supported the Portuguese and helped them connect with nearby countries. They had a lot to gain from the protection and connections the Portuguese offered.

The Portuguese first reached China in 1513. Jorge Álvares sailed from Malacca with five ships. He landed on an island in the Pearl River Delta and put up a stone pillar. Then, Rafael Perestrello landed in mainland China and traded profitably at Guangzhou. The protection that Albuquerque gave to the Chinese merchants living in Malacca helped the Portuguese be well received in China.

On June 17, 1517, eight ships led by Fernão Peres de Andrade reached Guangzhou. They carried an embassy from King Manuel I of Portugal. The ambassador, Tomé Pires, arrived with great ceremony and was welcomed by Chinese officials. Pires and his companions were given one of the best houses in the city. Important residents visited them often. Andrade moved his ships to the Island of Tamão. There, he got permission from the Ming authorities to open a trade post. He announced that anyone with complaints against the Portuguese should come to him. This made the Chinese think highly of the Portuguese's honesty.

Pires reached Beijing in January 1521. However, an ambassador from Sultan Mahmud asked Emperor Zhengde for help against the Portuguese. Emperor Zhengde died soon after. His successor, Jiajing, ordered that the Portuguese embassy be held hostage at Guangzhou. They would be released only if the Portuguese returned Malacca to Sultan Mahmud. Most of the embassy members had their belongings stolen and were imprisoned. Many died in captivity or were executed. Portuguese presence in China was banned. Still, many Portuguese continued to sail from Malacca to trade or smuggle goods.

Relations with China slowly got better. The Portuguese helped fight against the Wokou pirates along China's coast. By 1557, Ming China agreed to let the Portuguese settle at Macau. The Sultanate of Johor also improved relations with the Portuguese. They even fought together against the Aceh Sultanate.

Dutch Conquest and the End of Portuguese Malacca

By the early 1600s, the Dutch East India Company (called VOC in Dutch) began to challenge Portuguese power in the East. At that time, the Portuguese had made Malacca a very strong fortress, called the Fortaleza de Malaca. This fortress controlled access to the sea routes of the Strait of Malacca and the spice trade. It had even fought off an attack from Aceh in 1568.

The Dutch started with small attacks against the Portuguese. The first major attempt was the siege of Malacca in 1606. This was done by the third VOC fleet, with eleven ships, led by Admiral Cornelis Matelief de Jonge. It led to the battle of Cape Rachado. Even though the Dutch were defeated, the Portuguese fleet, led by Martim Afonso de Castro, suffered more losses. This battle brought the forces of the Sultanate of Johor into an alliance with the Dutch, and later with the Aceh Sultanate. The Dutch attacked Malacca again in 1616.

Around the same time, the Sultanate of Aceh had become a strong regional power with a powerful navy. They saw Portuguese Malacca as a threat. In 1629, Iskandar Muda of the Aceh Sultanate sent hundreds of ships to attack Malacca. However, this mission was a huge failure. Portuguese records say that all his ships were destroyed, and Aceh lost about 19,000 men.

The Dutch, with their local allies, attacked and captured Malacca from the Portuguese in January 1641. This combined effort by the Dutch, Johor, and Aceh effectively destroyed the last stronghold of Portuguese power in the area. It greatly reduced their influence in the islands. The Dutch then settled in the city, which became Dutch Malacca. However, the Dutch did not intend to make Malacca their main base. They focused on building Batavia (now Jakarta) as their headquarters in the East. The Portuguese ports in the spice-producing Maluku Islands also fell to the Dutch in the following years. After these conquests, the last Portuguese colonies in Asia were only Goa, Daman and Diu in Portuguese India, Portuguese Timor, and Macau. These remained Portuguese until the 20th century.

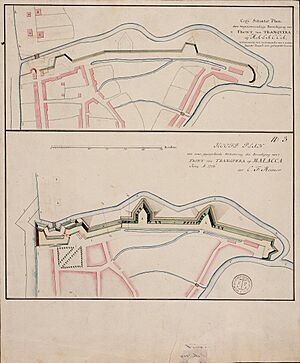

Fortress of Malacca

The first part of the fortress was a square tower called Fortaleza de Malaca. It was 10 fathoms (about 18 meters) on each side and 40 fathoms (about 73 meters) high. It was built at the bottom of the fortress hill, near the sea. A round wall of mortar and stone, with a well in the middle, was built to its east.

Over the years, more parts were built to fully fortify the fortress hill. The fortress system started at the farthest point of the cape, near the south-east of the river mouth. From there, it went towards the west of the Fortaleza. At this point, two walls were built at right angles to each other, along the shores. One wall ran north towards the river mouth for 130 fathoms (about 238 meters) to the bastion of São Pedro. The other wall ran for 75 fathoms (about 137 meters) to the east, curving inland, and ending at the gate and bastion of Santiago.

From the bastion of São Pedro, the wall turned north-east for 150 fathoms (about 274 meters). It passed the Custom House Terrace gateway and ended at the northernmost point of the fortress, the bastion of São Domingos. From the gateway of São Domingos, an earth wall ran south-east for 100 fathoms (about 183 meters). It ended at the bastion of the Madre de Deus. From here, starting at the gate of Santo António, past the bastion of the Virgins, the wall ended at the gateway of Santiago. In total, the city's enclosure was about 655 fathoms (about 1.2 kilometers) long.

Gateways of the Fortress

There were four main gates for the city:

- Porta de Santiago

- The gateway of the Custom House Terrace

- Porta de São Domingos

- Porta de Santo António

Only two of these gates were commonly used for people and traffic. These were the Gate of Santo António, which led to the Yler suburb, and the western gate at the Custom House Terrace, which gave access to Tranqueira and its market.

Legacy of the Fortress

After almost 300 years, in 1806, the British ordered the fortress to be slowly destroyed. They did not want to maintain it and were worried about other European powers taking control of it. The fort was almost completely torn down. However, Sir Stamford Raffles visited Malacca in 1810 and stopped its destruction. The only part left of this early Portuguese fortress in Southeast Asia is the Porta de Santiago, which is now known as the A Famosa.

Districts of Malacca Town During Portuguese Rule

Malacca was one of the most described cities in Southeast Asia during the 16th and 17th centuries because it was under Portuguese control. Outside the main fortified town center, there were three suburbs of Malacca. One suburb was Upe (Upih), usually called Tranqueira (which is modern-day Tengkera). It was named after the wall of the fortress. The other two suburbs were Yler (Hilir) or Tanjonpacer (Tanjung Pasir) and the suburb of Sabba.

Tranqueira District

This suburb was shaped like a rectangle. It had a northern border wall, the Strait of Malacca to the south, and the Malacca River and the fortress wall to the east. It was the main living area of the city. However, during wars, the people living there would be moved into the fortress for safety.

Tranqueira was divided into two smaller areas: São Tomé and São Estêvão. The São Tomé area was called Campon Chelim (Malay: Kampung Keling). It was said that this area was home to the Chelis from Choromandel. The other area, São Estêvão, was also called Campon China (Kampung Cina).

Erédia described the houses as being made of wood but with tile roofs. A stone bridge with guards crossed the Malacca River. This bridge provided access to the Malacca Fortress through the eastern Custom House Terrace. The city's main trading area was also in Tranqueira, near the beach at the river's mouth. It was called the Bazaar of the Jaos (Javanese). Today, this part of the city is called Tengkera.

Yler District

The Yler (Hilir) district generally covered Buquet China (Bukit Cina) and the south-eastern coastal area. The Well of Buquet China was a very important source of water for the people. Important places included the Church of the Madre De Deus and the Convent of the Capuchins of São Francisco. Other notable places included Buquetpiatto (Bukit Piatu). The edges of this suburb, which had no walls, were said to reach as far as Buquetpipi and Tanjonpacer.

Tanjonpacer (Malay: Tanjung Pasir) was later renamed Ujong Pasir. A community of people descended from Portuguese settlers still lives there in modern Malacca. However, this Yler suburb is now known as Banda Hilir. Today, new land has been created from the sea (to build the commercial area of Melaka Raya). This means Banda Hilir no longer has direct access to the sea, which it used to have.

Sabba District

The houses in this suburb were built along the riverbanks. Some of the original Muslim Malay people of Malacca lived in the swampy areas with nypeiras trees. They were known for making nypa (nipah) wine to trade. This suburb was considered the most rural. It was a transition area to the Malacca countryside. Timber and charcoal were brought through here into the city. Several Christian churches were also located outside the city along the river. These included São Lázaro, Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Our Lady of Hope. Meanwhile, Muslim Malays lived on the farmlands deeper in the countryside.

In later periods, under Dutch, British, and modern Malacca, the name Sabba was no longer used. However, its area included parts of what are now Banda Kaba, Bunga Raya, and Kampung Jawa within the modern city center of Malacca.

Portuguese Immigration to Malacca

Portuguese residents in Malacca were divided into five main groups:

- Soldados: These were soldiers, usually single men. Their job was to defend the city if it was attacked.

- Casados: These were married settlers. They were directly governed by the official Portuguese administration. This group included fidalgos (noblemen), retired soldiers, and lower-class citizens who moved there. Since there were many more men than women, these settlers often married local Asian women. This led to children of mixed heritage.

- Moradores: These were informal settlers. They were not under the direct control of the official administration. They settled in areas outside the main Portuguese view, but with Portuguese permission. They were often merchants and set up long-term communities.

- Ministrios: These were officials appointed by the Portuguese king for short stays. This included the captain-major. Other officials included the ouvidor (a judge) and vedor da fazenda (a financial manager).

- Religioso: This group included church officials. These were Catholic officials sent with the Pope's blessing to the Bishopric of Malacca. This area was under the control of the Archbishopric in Goa, which was set up in 1557. The Catholic priests were from different religious orders like the Capuchins, Augustinians, and Dominicans. Malacca was also a stop for Jesuit priests traveling to Japan and China, including Francis Xavier.

The Portuguese also sent many Órfãs do Rei to their colonies overseas. Órfãs do Rei means "Orphans of the King." These were Portuguese girl orphans sent to colonies like Africa, India, and Portuguese Malacca to marry Portuguese settlers there.

How Portuguese Malacca Was Governed

Portuguese Malacca was under the authority of Portuguese India, which was based in Goa. The governor or viceroy there oversaw its rule. Malacca itself was managed by the captain-major, whose office was inside the Fortaleza (the fortress).

In 1552, Malacca was given a special permission to become a city with its own city senate. This senate usually included fidalgos (noblemen), procuradores dos mesteres (representatives of trade guilds), and citizens who spoke for groups that were not well-represented. The city senate represented the interests of the casados (married settlers) and used it to communicate with the Portuguese King.

Another important organization in the city was the Misericordia, or the House of Mercy. This was a group dedicated to helping Christians in Malacca, no matter their background. They provided aid, medicine, and basic education. The group's leadership was called the mesa and was headed by a provedor. They also managed the money for people who left their assets to the Misericordia in their wills.

For local matters, the way Malacca was run before the Portuguese conquest mostly stayed the same. Afonso de Albuquerque first wanted the sultan to return and rule under Portuguese supervision. The positions of bendahara (chief minister), temenggung (chief of security), and shahbandar (harbor master) were kept. People from the non-Muslim communities of Malacca were appointed to these roles.

In 1571, King Sebastian tried to create three separate parts for his Asian colonies, with Malacca being one sector under its own governor. However, this plan did not happen.

According to Erédia in 1613, Malacca was managed by a governor (a captain-major), who served for three years. There was also a bishop and church leaders representing the church, city officials, royal officials for money and justice, and a local native bendahara to manage the local Muslims and foreigners under Portuguese rule.

| No. | Captain Major | From | Until | Monarch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ruy de Brito Patalim | 1512 | 1514 | Manuel I |

| 2 | Jorge de Alburquerque (1st time) | 1514 | 1516 | |

| 3 | Jorge de Brito | 1516 | 1517 | |

| 4 | Nuno Vaz Pereira | 1517 | 1518 | |

| 5 | Alfonso Lopes da Costa | 1518 | 1520 | |

| 6 | Jorge de Alburquerque (2nd time) | 1521 | 1525 | Manuel I |

| 7 | Pedro Mascarenhas | 1525 | 1526 | John III |

| 8 | Jorge Cabral | 1526 | 1528 | |

| 9 | Pero de Faria | 1528 | 1529 | |

| 10 | Garcia de Sà (1st time) | 1529 | 1533 | |

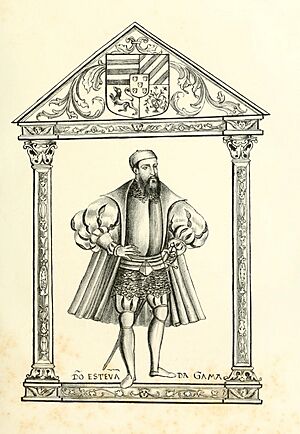

| 11 | Dom Paulo da Gama | 1533 | 1534 | |

| 12 | Dom Estêvão da Gama | 1534 | 1539 | |

| 13 | Pero de Faria | 1539 | 1542 | |

| 14 | Ruy Vaz Pereira | 1542 | 1544 | |

| 15 | Simão Botelho | 1544 | 1545 | |

| 16 | Garcia de Sà (2nd time) | 1545 | 1545 | |

| 17 | Simão de Mello | 1545 | 1548 | |

| 18 | Dom Pedro da Silva da Gama | 1548 | 1552 | |

| 19 | Licenciado Francisco Alvares | 1552 | 1552 | |

| 20 | Dom Alvaro de Ata de Gama | 1552 | 1554 | |

| 21 | Dom Antonio de Noronha | 1554 | 1556 | |

| 22 | Dom João Pereira | 1556 | 1557 | |

| 23 | João de Mendonça | 1557 | 1560 | John III |

| 24 | Francisco Deça | 1560 | 1560 | Sebastian I |

| 25 | Diogo de Meneses | 1564 | 1567 | |

| 26 | Leonis Pereira | 1567 | 1570 | |

| 27 | Francisco da Costa | 1570 | 1571 | |

| 28 | António Moniz Barreto | 1571 | 1573 | |

| 29 | Miguel de Castro | 1573 | 1573 | |

| 30 | Leonis Pereira ou Francisco Henriques de Meneses | 1573 | 1574 | |

| 31 | Tristão Vaz da Veiga | 1574 | 1575 | |

| 32 | Miguel de Castro | 1575 | 1577 | |

| 33 | Aires de Saldanha | 1577 | 1579 | Sebastian I |

| 34 | João da Gama | 1581 | 1582 | Philip I |

| 35 | Roque de Melo | 1582 | 1584 | |

| 36 | João da Silva | 1584 | 1587 | |

| 37 | João Ribeiro Gaio | 1587 | 1587 | |

| 38 | Nuno Velho Pereira | 1587 | 15xx | |

| 39 | Diogo Lobo | 15xx | 15xx | |

| 40 | Pedro Lopes de Sousa | 15xx | 1594 | |

| 41 | Francisco da Silva Meneses | 1597 | 1598 | |

| 42 | Martim Afonso de Melo Coutinho | 1598 | 1599 | Philip I |

| 43 | Fernão de Albuquerque | 1599 | 1603 | Phillip II |

| 44 | André Furtado de Mendonça | 1603 | 1606 | |

| 45 | António de Meneses | 1606 | 1607 | |

| 46 | Francisco Henriques | 1610 | 1613 | |

| 47 | Gaspar Afonso de Melo | 1613 | 1615 | |

| 48 | João Calado de Gamboa | 1615 | 1615 | |

| 49 | António Pinto da Fonseca | 1615 | 1616 | |

| 50 | João da Silveira | 1617 | 1617 | |

| 51 | Pedro Lopes de Sousa | 1619 | 1619 | |

| 52 | Filipe de Sousa ou Francisco Coutinho | 1624 | 1624 | Phillip III |

| 53 | Luis de Melo | 162. | 1626 | |

| 54 | Gaspar de Melo Sampaio | 16xx | 1634 | |

| 55 | Álvaro de Castro | 1634 | 1635 | |

| 56 | Diogo de Melo e Castro | 1630 | 1633 | |

| 57 | Francisco de Sousa de Castro | 1630 | 1636 | |

| 58 | Diogo Coutinho Docem | 1635 | 1637 | |

| 59 | Manuel de Sousa Coutinho | 1638 | 1641 | Phillip III |

Military History of Portuguese Malacca

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1511 | Conquest of Malacca |

| 1520 | Battle of Pago |

| 1521 | Battle of Bintan |

| Battle of Aceh | |

| 1522 | Pedir Expedition |

| 1523 | Battle of Muar River |

| 1524 | Siege of Pasai |

| Siege of Malacca | |

| 1525 | Battle of Lingga |

| 1526 | Siege of Bintan |

| 1528 | Battle of Aceh |

| 1535 | Battle of Ugentana |

| 1536 | Second Battle of Ugentana |

| 1537 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1547 | Battle of Perlis River |

| 1551 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1568 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1569 | Battle of Aceh |

| 1570 | First Battle of Formoso River |

| 1573 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1574 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1575 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1587 | Siege of Johor |

| 1606 | Battle of Aceh |

| Siege of Malacca | |

| Battle of Cape Rachado | |

| 1607 | Johor expedition |

| 1615 | Second Battle of Formoso River |

| 1616 | Battle of Malacca |

| 1629 | Battle of Duyon River |

| 1641 | Siege of Malacca |

Gallery

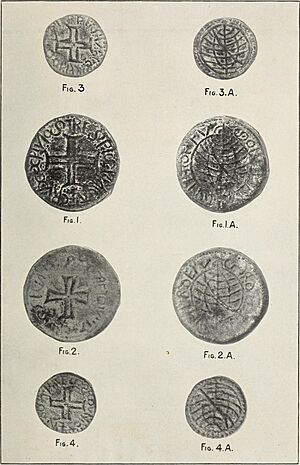

Currency

See also

- Fortress of Malacca

- Portuguese Settlement, Malacca

- Portuguese Well

- Malay-Portuguese conflicts

- Acehnese-Portuguese conflicts

- Luso-Asians

- Códice Casanatense

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |