Khmer Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kambuja

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 802–1431 | |||||||||||||

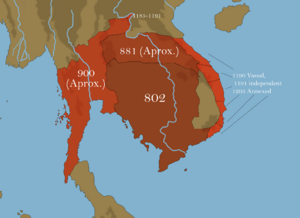

The Khmer Empire (Kambuja), c. 900

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy ruled by a divine king | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

|

• 802–850

|

Jayavarman II (first) | ||||||||||||

|

• 1417–1431

|

Borom Reachea II (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-classical | ||||||||||||

|

• Enthronement of Jayavarman II

|

802 | ||||||||||||

|

• Construction of Angkor Wat

|

1113–1150 | ||||||||||||

|

• Fall of Angkor

|

1431 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1290 | 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The Khmer Empire was a powerful kingdom in Southeast Asia. It was a Hindu and Buddhist empire. It was known as Kambuja by its people. The empire grew from an older civilization called Chenla. It lasted from the 9th century to the 15th century.

Historians call this time in Cambodian history the Angkor period. This is because Angkor was the empire's most famous capital city. At its strongest, the Khmer Empire controlled much of mainland Southeast Asia. It even reached as far north as southern China.

The Khmer Empire officially began in 802. This is when Prince Jayavarman II declared himself chakravartin. This means "universal ruler" or emperor. He did this in the Phnom Kulen mountains. The empire is traditionally said to have ended in 1431. This was when Angkor fell to the Ayutthaya Kingdom from Siam.

The reasons for the empire's fall are still debated. Scientists have found that the region had very heavy monsoon rains. This was followed by a severe drought. These extreme weather changes damaged the empire's water systems. This might have caused people to move away from the big cities.

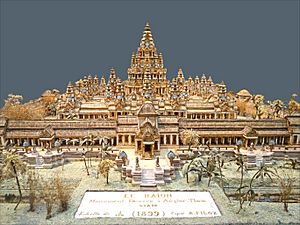

The city of Angkor is the empire's most famous legacy. It was the capital during the empire's best years. Amazing buildings like Angkor Wat and Bayon show the Khmer Empire's power and wealth. They also show its impressive art, building skills, and different religions. Satellite images show that Angkor was the largest pre-industrial city in the world. This was between the 11th and 13th centuries. Researchers also believe the Khmer Empire created the world's first healthcare system. It had 102 hospitals!

Contents

What Does "Khmer Empire" Mean?

Modern experts often call it the "Khmer Empire" (Khmer: ចក្រភពខ្មែរ). Sometimes it's called the "Angkor Empire" (Khmer: ចក្រភពអង្គរ). This name comes from its capital city, Angkor.

The people of the empire called themselves Kambuja (Sanskrit: कम्बुज; Old Khmer: កម្វុជ). They also used Kambujadeśa (Sanskrit: कम्बुजदेश). These names are older versions of the modern name Kampuchea.

How We Know About the Khmer Empire

We don't have many written records from the Angkor period. Most of what we know comes from a few main sources:

- Archaeology: This involves digging up old sites and studying ancient objects.

- Stone Inscriptions: These are writings carved into stone. They tell us about the kings' political and religious actions.

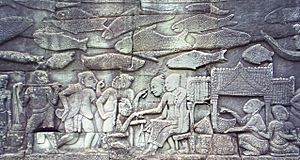

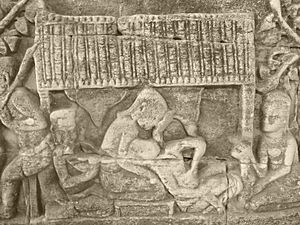

- Temple Reliefs: These are carvings on temple walls. They show scenes of daily life, markets, armies, and palace activities.

- Chinese Records: Chinese diplomats, traders, and travelers wrote reports about their visits.

History of the Khmer Empire

How the Empire Began and Grew

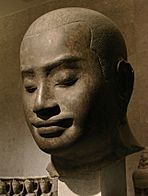

Jayavarman II: The First King

Around 781, a Khmer prince named Jayavarman II started his rule. He made Indrapura his first capital. This city was near modern-day Kampong Cham. He quickly gained power and defeated other kings. In 790, he became king of a kingdom called Kambuja. He then moved his court to Mahendraparvata, which is inland from Tonlé Sap lake.

Jayavarman II (ruled 802–835) is seen as the founder of the Angkor period. Historians agree this period began in 802. That year, Jayavarman II held a special Hindu ceremony. He declared himself chakravartin (universal ruler) and devaraja (god king). He also announced Kambuja's freedom from a place called "Java."

Historians debate what "Java" meant. It could be the Indonesian island of Java, Champa, or another place. Some believe Jayavarman II lived in Java and brought ideas from there. Others think he had more contact with the Chams, who were neighbors to the east. Early temples on Phnom Kulen show both Cham and Javanese influences.

Later, Jayavarman II built a new capital called Hariharalaya. This was near the modern town of Roluos. He set the stage for Angkor, which would be built about 15 kilometers away. Jayavarman II died in 835. His son, Jayavarman III, became king after him.

Expanding the Kingdom

Jayavarman II's successors continued to expand Kambuja. Indravarman I (ruled 877–889) grew the kingdom without wars. He started big building projects. These were possible because of wealth from trade and farming. He built the temple of Preah Ko and irrigation systems. Indravarman I also developed Hariharalaya by building Bakong around 881. Bakong looks very similar to the Borobudur temple in Java. This suggests that ideas and building techniques were shared between the two kingdoms.

Yasodharapura Becomes the Capital

Indravarman I's son, Yasovarman I (ruled 889–915), built a new capital. It was called Yasodharapura, the first city of Angkor. The main temple was on Phnom Bakheng, a hill about 60 meters high. Under Yasovarman I, the huge East Baray water reservoir was also created. It was 7.1 by 1.7 kilometers in size.

In the early 10th century, the kingdom split. Jayavarman IV made a new capital at Koh Ker, about 100 kilometers northeast of Angkor. The royal palace returned to Yasodharapura only with Rajendravarman II (ruled 944–968). He continued the building projects of earlier kings. He built temples like the East Mebon and several Buddhist temples. In 950, the first war happened between Kambuja and the kingdom of Champa to the east.

Jayavarman V ruled from 968 to 1001. His rule was mostly peaceful and prosperous. He built a new capital called Jayendranagari. Its state temple was Ta Keo. Philosophers, scholars, and artists lived at his court. Important temples like Banteay Srei and Ta Keo were built. Banteay Srei is known for being one of Angkor's most beautiful temples.

After Jayavarman V died, there was a decade of conflict. Three kings ruled at the same time. Finally, Suryavarman I (ruled 1006–1050) took the throne. He made alliances with the Chola dynasty in South India. His rule saw many attempts to overthrow him and military victories. Suryavarman I took control of Angkor Wat.

Angkor Wat also faced conflict with the Tambralinga kingdom. Suryavarman asked for help from the Chola Emperor Rajendra Chola I. The Tambralinga kingdom then asked for help from the Srivijaya King. This led to a war between the Chola and Srivijaya Empires. The Chola and Khmer Empires won. This alliance also had a religious side. Both Chola and Khmer were Hindu, while Tambralinga and Srivijaya were Buddhist. Suryavarman I's wife was Viralakshmi. After he died in 1050, Udayadityavarman II became king. He built the Baphuon and West Baray.

The Golden Age of Khmer Civilization

Suryavarman II and Angkor Wat

The 12th century was a time of many conflicts. Under Suryavarman II (ruled 1113–1150), the kingdom became strong and united. The huge temple of Angkor Wat was built in 37 years. It was dedicated to the god Vishnu.

His wars against Champa and Dai Viet in the east were not successful. However, he did attack Vijaya in 1145. He sent a mission to the Chola dynasty in South India. He gave a precious stone to the Chola emperor in 1114.

After this, kings ruled for short times and were often overthrown. In 1177, the capital was attacked and looted. A Cham fleet attacked in a naval battle on the Tonlé Sap lake. King Tribhuvanadityavarman was killed.

Jayavarman VII and Angkor Thom

King Jayavarman VII (ruled 1181–1219) is often called Cambodia's greatest king. He was a military leader before becoming king. After the Cham conquered Angkor, he gathered an army and took back the capital. He became king and fought the Cham for 22 more years. The Khmer defeated Champa in 1203 and took over much of its land.

Jayavarman VII was the last of Angkor's great kings. He was successful in war and was not a harsh ruler. He united the empire and started many important building projects. The new capital, Angkor Thom (meaning "Great City"), was built. In its center, the king built the Bayon temple. It had stone towers with huge faces of the boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Other important temples built by Jayavarman VII include Ta Prohm (for his mother) and Preah Khan (for his father). He also built Banteay Kdei, Neak Pean, and the Srah Srang reservoir. He created a large network of roads connecting all towns. There were rest-houses for travelers and 102 hospitals across his kingdom.

Jayavarman VIII's Rule

After Jayavarman VII died, his son Indravarman II (ruled 1219–1243) became king. He was a Buddhist like his father. He finished some temples his father had started. But he was not as good at fighting. In 1220, the Khmer lost control of many lands they had taken from Champa.

Indravarman II was followed by Jayavarman VIII (ruled 1243–1295). Unlike earlier kings, Jayavarman VIII was a Hindu. He was against Buddhism. He destroyed many Buddha statues and changed Buddhist temples into Hindu ones. From outside, the empire was threatened by the Mongols in 1283. Their general, Sogetu, was the governor of Guangzhou, China. The king avoided war by paying a yearly tribute to the Mongols starting in 1285.

Jayavarman VIII's rule ended in 1295. He was overthrown by his son-in-law, Srindravarman (ruled 1295–1309). The new king followed Theravada Buddhism. This type of Buddhism came from Sri Lanka and spread throughout Southeast Asia.

In August 1296, a Chinese diplomat named Zhou Daguan arrived in Angkor. He wrote that "the country was utterly devastated" from a recent war with the Siamese. He stayed until July 1297. Zhou Daguan wrote a detailed report about life in Angkor. It is one of the most important sources for understanding historical Angkor. He described temples like the Bayon and Angkor Wat. He also gave valuable information about the daily life of Angkor's people.

Decline of the Empire

By the 14th century, the Khmer Empire slowly declined. Historians suggest several reasons for this decline:

- Changes in religion from Hinduism to Theravada Buddhism. This affected society and politics.

- Constant power struggles among Khmer princes.

- Rebellions by smaller states that were under Khmer rule.

- Foreign invasions.

- Diseases like the plague.

- Environmental problems.

Many things contributed to the decline. The relationship between rulers and their nobles was unstable. Many kings did not have a clear right to the throne. Civil wars were common. The empire focused more on its own economy and less on international trade. Also, Buddhist ideas clashed with the Hindu system that the state was built on.

Changing Religions

The last Sanskrit inscription is from 1327. It describes the next king, Jayavarmadiparamesvara. Historians think this is linked to kings adopting Theravada Buddhism. Kings were no longer seen as "devarajas" (god kings). So, there was no need to build huge temples for them or their gods. Moving away from the devaraja idea might have weakened the king's power. This could have led to fewer workers for big projects.

The water management system also broke down. This meant harvests were reduced by floods or droughts. Before, three rice harvests a year were possible. This brought great wealth to Kambuja. Declining harvests further weakened the empire.

Archaeologists noticed that not only did building stop, but historical inscriptions also disappeared. This happened between 1300 and 1600. Because of this, there is little archaeological evidence from that time. Archaeologists have found that sites were abandoned and later reoccupied by different people.

Pressure from Other Kingdoms

The Ayutthaya Kingdom grew strong in the 14th century. It became Angkor's main rival. Angkor was attacked by the Ayutthayan king Uthong in 1352. After it was captured, Siamese princes ruled the Khmer. In 1357, the Khmer king Suryavamsa Rajadhiraja took back the throne.

In 1393, the Ayutthayan king Ramesuan attacked Angkor again. He captured it the next year. Ramesuan's son ruled for a short time before being killed. Finally, in 1431, the Khmer king Ponhea Yat left Angkor. He moved to the Phnom Penh area because Angkor was too hard to defend.

The new center of the Khmer kingdom was in the southwest, at Oudong. This is near modern-day Phnom Penh. However, Angkor might not have been completely abandoned. One line of Khmer kings might have stayed there. Another moved to Phnom Penh to create a parallel kingdom. The final fall of Angkor might have been due to Phnom Penh becoming an important trade center on the Mekong river. This shifted economic and political power. Also, severe droughts and floods contributed to its fall.

Environmental Problems

Environmental problems are a newer idea for why the Khmer Empire ended. Scientists working on the Greater Angkor Project believe the Khmer had a complex system of reservoirs and canals. These were used for trade, transport, and irrigation. The canals were vital for growing rice. As the population grew, the water system was put under more stress.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, there were also big climate changes. Long periods of drought led to less food production. Then, strong monsoon floods damaged the water systems. To feed the growing population, trees were cut down from the Kulen hills. This cleared land for more rice fields. But this caused rain to wash soil into the canals. Any damage to the water system would have huge consequences.

The Plague Theory

The idea that a severe disease outbreak, like the plague, contributed to Angkor's fall has been considered. By the 14th century, the Black Death affected Asia. It appeared in China around 1330 and reached Europe around 1345. Many seaports along the trade routes from China to Europe were hit by the disease. This could have greatly impacted life throughout Southeast Asia. Possible diseases include bubonic plague, smallpox, and malaria.

Angkor After the 15th Century

There is evidence that Angkor was still used after the 15th century. Under King Barom Reachea I (ruled 1566–1576), the royal court briefly returned to Angkor. He managed to push back Ayutthaya for a time. Inscriptions from the 17th century show that Japanese people lived there alongside the remaining Khmer. One inscription tells of Ukondayu Kazufusa, who celebrated the Khmer New Year there in 1632. However, the Japanese community eventually blended into the local Khmer community. This was because no new Japanese people arrived.

Khmer Culture and Society

Much of what we know about ancient Khmer society comes from temple carvings. We also learn from the detailed accounts of the Chinese traveler Zhou Daguan. His writings give us information about 13th-century Cambodia. The carvings on Angkor temples, like those in Bayon, show daily life. They depict palace scenes, naval battles, and market activities.

Economy and Farming

The ancient Khmers were mainly farmers. They relied heavily on rice farming. Most people in the kingdom were farmers. They planted rice near lakes, rivers, or in irrigated plains. Sometimes they farmed in the hills when lowlands flooded. A huge and complex water system irrigated the rice fields. This system included canals and barays, which were giant water reservoirs. This allowed for large-scale rice farming around Khmer cities. Farmers also grew sugar palm trees, fruit trees, and vegetables. These provided palm sugar, palm wine, coconuts, and various fruits and vegetables.

Many Khmer people lived near the large Tonlé Sap lake and many rivers. They relied on fresh water fishing for food. Fish was their main source of protein. They made it into prahok, a dried or steamed fish paste. Rice was the main food along with fish. They also raised pigs, cattle, and chickens. These animals were kept under their houses, which were built on stilts to protect from floods.

The market in Angkor had no permanent buildings. It was an open square where traders sat on straw mats on the ground. They sold their goods without tables or chairs. Some traders used simple thatched umbrellas for shade. Officials collected a tax or rent for each space traders used. Women mainly ran the trade and economy in the Angkor marketplace.

Zhou Daguan wrote about the women of Angkor:

The local people who know how to trade are all women. So when a Chinese goes to this country, the first thing he must do is take in a woman, partly with a view to profiting from her trading abilities.

The women age very quickly, no doubt because they marry and give birth when too young. When they are twenty or thirty years old, they look like Chinese women who are forty or fifty.

The important role of women in trade shows they had many rights and freedoms. Marrying early might have led to a high birth rate and a large population.

Society and Politics

The Khmer Empire was built on many farming communities. Villages were grouped around regional centers. These centers sent goods to large cities like Angkor. In return, they received items like pottery and foreign goods from China. The king and his officials managed the irrigation and water distribution. This involved a complex system of canals, moats, and large reservoirs called barays.

Society was organized like the Hindu caste system. Common people, like farmers and fishermen, made up most of the population. The kshatriyas were the ruling class. This included royalty, nobles, military leaders, and soldiers. Other groups were brahmins (priests), traders, and skilled workers like carpenters and stonemasons. At the lowest level were slaves.

The large irrigation projects created extra rice. This could support a huge population. The official religion was Hinduism. It was influenced by the cult of Devaraja. This belief made Khmer kings seem like living gods on Earth. They were thought to be incarnations of Vishnu or Shiva. This idea gave kings a divine reason to rule. It also allowed them to build massive projects. They constructed grand monuments like Angkor Wat and Bayon to celebrate their divine rule.

The King was surrounded by ministers, officials, nobles, and servants. The capital city of Angkor was known for its grand ceremonies. Many festivals and rituals were held there. Even when traveling, the King and his group created a big spectacle. Zhou Daguan described a royal procession:

When the king goes out, troops are at the head of [his] escort; then come flags, banners and music. Palace women, numbering from three to five hundred, wearing flowered cloth, with flowers in their hair, hold candles in their hands, and form a troupe. Even in broad daylight, the candles are lighted. Then come other palace women, bearing royal paraphernalia made of gold and silver... Then come the palace women carrying lances and shields, with the king's private guards. Carts drawn by goats and horses, all in gold, come next. Ministers and princes are mounted on elephants, and in front of them one can see, from afar, their innumerable red umbrellas. After them come the wives and concubines of the king, in palanquins, carriages, on horseback and on elephants. They have more than one hundred parasols, flecked with gold. Behind them comes the sovereign, standing on an elephant, holding his sacred sword in his hand. The elephant's tusks are encased in gold.

Zhou Daguan also described the Khmer king's clothes:

Only the ruler can dress in cloth with an all-over floral design...Around his neck he wears about three pounds of big pearls. At his wrists, ankles and fingers he has gold bracelets and rings all set with cat's eyes...When he goes out, he holds a golden sword [of state] in his hand.

Khmer kings often fought wars and conquered lands. Angkor's large population allowed the kingdom to have big armies. These armies were used to conquer neighboring areas. Khmer kings fought wars against Champa, Dai Viet, and Thai warlords. Kings and royal families were also often involved in power struggles over who would rule next.

Military

The Chinese traveler Zhou Daguan visited Angkor between 1296 and 1297. He wrote that the Sukhothai Kingdom often destroyed Khmer lands in wars. Zhou said that Khmer soldiers fought without clothes or shoes. They used only lances and shields. They did not use bows and arrows in land battles, catapults, body armor, or helmets. When Sukhothai attacked, ordinary people were ordered to fight without a plan. The Khmer did have double-bow crossbows on elephants.

Zhou described the walls of Angkor Thom as 10 kilometers long. They had five gateways, each with two gates. A large moat surrounded the walls, with bridges crossing it. The stone walls were very strong and about 6–7 meters high. They were thick enough to have rooms inside. There were no battlements, only one stone tower on each of the four sides. Guards worked there, but dogs were not allowed on the walls. According to an old story told to Henri Mouhot, the Khmer Empire had an army of 5-6 million soldiers.

Culture and Daily Life

Zhou Daguan described Khmer houses:

The dwellings of the princes and principal officials have a completely different layout and dimensions from those of the people. All the outlying buildings are covered with thatch; only the family temple and the principal apartment can be covered in tiles. The official rank of each person determines the size of the houses.

Farmers' houses were near the rice fields, at the edge of cities. Their walls were made of woven bamboo, with thatched roofs. They were built on stilts to protect from floods. A house had three rooms: parents' bedroom, daughters' bedroom, and a living area. Sons slept wherever they could find space. The kitchen was at the back or in a separate room. Nobles and kings lived in larger houses in the city. These were made of the same materials but had wooden shingle roofs. They also had fancy designs and more rooms.

Zhou Daguan reported that locals did not make silk. They also did not know how to sew with a needle and thread.

None of the locals produces silk. Nor do the women know how to stitch and darn with a needle and thread. The only thing they can do is weave cotton from kapok. Even then they cannot spin the yarn, but just use their hands to gather the cloth into strands. They do not use a loom for weaving. Instead they just wind one end of the cloth around their waist, hang the other end over a window, and use a bamboo tube as a shuttle.

In recent years people from Siam have come to live in Cambodia, and unlike the locals they engage in silk production. The mulberry trees they grow and the silkworms they raise all come from Siam. They themselves weave the silk into clothes made of a black, patterned satiny silk. Siamese women do know how to stitch and darn, so when local people have torn or damaged clothing they ask them to do the mending.

Common people wore a sampot. This was a cloth wrapped around the waist, with the front pulled between the legs and tied at the back. Nobles and kings wore finer, richer fabrics. Women wore a strip of cloth to cover their chest. Noble women had a longer one that went over the shoulder. Both men and women wore a Krama, a traditional scarf. The carvings on Bayon show daily life, including markets, fishermen, butchers, and people playing games or gambling during cockfighting.

Religion

The main religion was Hinduism, followed by Buddhism. At first, Hinduism was the official state religion. Vishnu and Shiva were the most worshipped gods in Khmer Hindu temples. Temples like Angkor Wat are known as Phitsanulok (realm of Vishnu). This honored King Suryavarman II after his death as Vishnu.

Hindu ceremonies were performed by Brahmins (Hindu priests). These were usually only for the king's family, nobles, and the ruling class. The empire's official religions included Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. Later, Theravada Buddhism became popular, even among common people. It was introduced from Sri Lanka in the 13th century.

Art and Architecture

Zhou Daguan described the Angkor Royal Palace:

All official buildings and homes of the aristocracy, including the Royal Palace, face the east. The Royal Palace stands north of the Golden Tower and the Bridge of Gold: it is one and a half mile in circumference. The tiles of the main dwelling are of lead. Other dwellings are covered with yellow-coloured pottery tiles. Carved or painted Buddhas decorate all the immense columns and lintels. The roofs are impressive too. Open corridors and long colonnades, arranged in harmonious patterns, stretch away on all sides.

The Khmer Empire built many temples and grand monuments. These celebrated the divine power of Khmer kings. Khmer architecture shows the Hindu belief that temples were built to look like the home of Hindu gods, Mount Meru. Mount Meru has five peaks, surrounded by seas. In temples, ponds and moats represented these seas. Early Khmer temples in Angkor, like Bakong, used stepped pyramid shapes. These represented the sacred temple-mountain.

Khmer art and architecture reached their best with the building of Angkor Wat. Other temples like Ta Phrom and Bayon were also built in Angkor. The construction of these temples shows the Khmer Empire's great artistic and technical skills in stone building.

Khmer Architectural Styles During the Angkor Period:

| Styles | Dates | Rulers | Temples | Main Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kulen | 825–875 | Jayavarman II | Damrei Krap | Continued older styles but added new ideas. Towers were mostly square and tall. Used brick with laterite walls and stone door frames. |

| Preah Ko | 877–886 | Indravarman I Jayavarman III | Preah Ko, Bakong, Lolei | Simple design: one or more square brick towers on a single base. First time using outer walls and gopura (gateways). First major temple mountain at Bakong. |

| Bakheng | 889–923 | Yasovarman I Harshavarman I | Phnom Bakheng, Phnom Krom, Phnom Bok, Baksei Chamkrong (trans.) | Temple mountains became more developed. More stone was used, especially for big temples and carvings. |

| Koh Ker | 921–944 | Jayavarman IV | Group of Koh Ker temples | Buildings got smaller towards the center. Brick was still used, but sandstone also appeared. |

| Pre Rup | 944–968 | Rajendravarman | Pre Rup, East Mebon, Bat Chum, Kutisvara | A mix of Koh Ker and Banteay Srei styles. Long halls partly enclosed the main area. Last big monuments made of plastered brick, more sandstone used. |

| Banteay Srei | 967–1000 | Jayavarman V | Banteay Srei | Very decorated with layered carvings. Rich and deep carvings. Stone and laterite replaced plastered brick. Scenes started appearing in the carvings. |

| Khleang | 968–1010 | Jayavarman V | Ta Keo, The Khleangs, Phimeanakas, Royal Palace | First use of galleries (long hallways). Cross-shaped gateways. Simpler carvings. |

| Baphuon | 1050–1080 | Udayadityavarman II | Baphuon, West Mebon | Rich carvings returned, with flower designs and scenes on lintels (door frames). Carvings at Baphuon showed lively scenes in small panels. |

| Angkor Wat | 1113–1175 | Suryavarman II Yasovarman II | Angkor Wat, Banteay Samré, Thommanon, Chau Say Tevoda, Beng Mealea, some of Preah Pithu, Phimai and Phnom Rung | The most famous style of Khmer architecture. Fully developed towers with carvings. Wider galleries. Outer walls connected by long hallways. Richly carved decorations. Apsara (heavenly dancers) carvings. |

| Bayon | 1181–1243 | Jayavarman VII Indravarman II | Ta Prohm, Preah Khan, Neak Pean, Ta Som, Ta Nei, Angkor Thom, Prasat Chrung, Bayon, Elephant terrace, Ta Prohm Kel, Krol Ko, Prasat Suor Prat, Banteay Chhmar, Hospital Chaples, Jayatataka baray | The last great style. Built quickly, often using laterite instead of stone. Carvings were less detailed. Complex designs, huge temples. In Cambodia, temples had face-towers and historical carvings. |

| Post Bayon | 1243–15th c. | Jayavarman VIII and others | Terrace of the Leper King, Preah Pithu, Preah Palilay (modifications to temples) | Changes to existing temples. Causeways (raised roads) on columns. |

Relations with Other Kingdoms

When the empire was forming, the Khmer had close ties with Java and the Srivijaya empire. These were located across the southern seas. In 851, a Persian merchant wrote about a Khmer king and a Maharaja of Zabaj. The story said a Khmer king challenged the Maharaja of Zabaj. The Javanese Sailendras then attacked the Khmers by surprise from the river. The young Khmer king was punished, and his kingdom became a vassal of the Sailendra dynasty.

Zabaj is an Arabic name for Javaka. It might refer to Java or Srivijaya. This story likely describes an early stage of the Khmer kingdom under Javanese control. The Kaladi inscription from Java (around 909 CE) mentioned Kmir (Khmer people) along with Campa (Champa) and Rman (Mon). These were foreigners from mainland Southeast Asia who often came to Java to trade. This suggests a sea trade network between Kambuja and Java.

In 916 CE, an Arab historian named Abu Zaid Hasan wrote that a young Khmer king was hostile to Java. When this hostility became official, the King of Java attacked and captured the Khmer king. The Khmer king was beheaded. The King of Java then ordered the Khmer Empire's minister to find a new ruler.

Throughout its history, the empire also fought wars with its neighbors. These included the kingdoms of Champa, Tambralinga, and Đại Việt. Later, it fought with the Siamese Sukhothai and Ayutthaya. The Khmer Empire's relationship with Champa was very intense. Both sides fought for control in the region. The Cham fleet attacked Angkor in 1177. In 1203, the Khmer pushed back and defeated Champa.

Arab writers from the 9th and 10th centuries did not mention the region much. But they considered the king of Al-Hind (India and Southeast Asia) one of the four great kings in the world. The ruler of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty was described as the greatest king of Al-Hind. Even lesser kings, like those of Java, Pagan Burma, and Cambodia, were seen as very powerful. They had huge armies of men, horses, and many elephants. They were also known to have vast treasures of gold and silver. The Khmer rulers also had relations with the Chola dynasty of South India.

The Khmer Empire kept in touch with Chinese dynasties. This was from the late Tang period to the Yuan period. Relations with the Yuan dynasty were very important. They led to The Customs of Cambodia (Chinese: 真臘風土記). This book gives great insight into the Khmer Empire's daily life, culture, and society. The report was written by the Yuan Chinese diplomat Zhou Daguan. He was sent by Temür Khan of the Yuan dynasty to stay in Angkor from 1296 to 1297.

Starting in the 13th century, Khmer's relations with the Siamese became difficult. This led to centuries of rivalry. In August 1296, Zhou Daguan wrote that the country was "utterly devastated" from a recent war with the Siamese. This report confirmed that Siamese warlords were rebelling. This marked the beginning of Siam's rise. By the 14th century, the Siamese Ayutthaya Kingdom became a strong rival. Angkor was attacked and captured twice by Ayutthayan invaders in 1353 and 1394. Ayutthaya adopted many Khmer traditions. These included a complex social system and the idea of kings as divine.

In the 1300s, the Lao prince Fa Ngum lived in the royal court of Angkor. His father-in-law, the King of Cambodia, gave him a Khmer army. Fa Ngum conquered local areas and created the Kingdom of Lan Xang. With help from Khmer scholars, Fa Ngum brought Theravada Buddhism and Khmer culture to the region.

A Javanese source from 1365, the Nagarakretagama, mentions Java's diplomatic ties with Kambuja (Cambodia). It also lists Syangkayodhyapura (Ayutthaya), Dharmmanagari, Rajapura, Singhanagari, Marutma, Champa, and Yawana (Annam). This record shows the political situation in Southeast Asia in the mid-14th century. The Cambodian kingdom still existed, but the rise of Siamese Ayutthaya was taking its toll. Finally, the empire fell. This was marked by the abandonment of Angkor for Phnom Penh in 1431, due to Siamese pressure.

List of Khmer Rulers

| Years Ruled | King | Capital | Important Information and Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 802–835 | Jayavarman II | Mahendraparvata, Hariharalaya | Declared Kambuja's freedom from Java. Became Chakravartin (universal ruler) through a Hindu ritual. Started the Devaraja (god king) cult. |

| 835–877 | Jayavarman III | Hariharalaya | Son of Jayavarman II. |

| 877–889 | Indravarman I | Hariharalaya | Nephew of Jayavarman II. Built Preah Ko temple. Constructed the temple mountain Bakong. |

| 889–910 | Yasovarman I | Hariharalaya, Yaśodharapura | Son of Indravarman I. Built Indratataka Baray and Lolei. Moved the capital to Yaśodharapura (Angkor). |

| 910–923 | Harshavarman I | Yaśodharapura | Son of Yasovarman I. Fought for power against his uncle Jayavarman IV. Built Baksei Chamkrong. |

| 923–928 | Ishanavarman II | Yaśodharapura | Son of Yasovarman I, brother of Harshavarman I. Also fought against his uncle Jayavarman IV. Built Prasat Kravan. |

| 928–941 | Jayavarman IV | Koh Ker | Claimed the throne through his mother. Ruled from Koh Ker. |

| 941–944 | Harshavarman II | Koh Ker | Son of Jayavarman IV. |

| 944–968 | Rajendravarman II | Angkor (Yaśodharapura) | Uncle and cousin of Harshavarman II. Took power from him. Moved the capital back to Angkor. Built Pre Rup and East Mebon. Fought a war against Champa in 946. |

| 968–1001 | Jayavarman V | Jayendranagari in Angkor | Son of Rajendravarman II. Built a new capital Jayendranagari and Ta Keo temple. |

| 1001–1006 | Udayadityavarman I, Jayaviravarman, Suryavarman I | Angkor | A time of disorder, three kings ruled at the same time. |

| 1006–1050 | Suryavarman I | Angkor | Took the throne. Formed an alliance with Chola and fought with Tambralinga kingdom. Built Preah Khan Kompong Svay. He was a follower of Mahayana Buddhism. |

| 1050–1066 | Udayadityavarman II | Yaśodharapura II (Angkor) | Took the throne. Built Baphuon, West Baray, West Mebon, and Sdok Kok Thom. |

| 1066–1080 | Harshavarman III | Yaśodharapura II (Angkor) | Succeeded his older brother Udayadityavarman II. Capital was at Baphuon. Champa invaded in 1074 and 1080. |

| 1090–1107 | Jayavarman VI | Angkor | Took the throne by force. Built Phimai. |

| 1107–1113 | Dharanindravarman I | Angkor | Succeeded his younger brother, Jayavarman VI. |

| 1113–1145 | Suryavarman II | Angkor | Took the throne by force and killed his great uncle. Built Angkor Wat, Banteay Samre, Thommanon, Chau Say Tevoda, and Beng Mealea. Invaded Đại Việt and Champa. |

| 1150–1160 | Dharanindravarman II | Angkor | Succeeded his cousin Suryavarman II. |

| 1160–1167 | Yasovarman II | Angkor | Overthrown by his minister Tribhuvanadityavarman. |

| 1167–1177 | Tribhuvanadityavarman | Angkor | Cham invasion in 1177 and 1178 led by Jaya Indravarman IV. The Khmer capital was looted. |

| 1178–1181 | Cham occupation, led by Champa king Jaya Indravarman IV | ||

| 1181–1218 | Jayavarman VII | Yaśodharapura (Angkor) | Led the Khmer army to free Cambodia from Cham invaders. Conquered Champa (1190–1191). Built many important structures: hospitals, rest houses, reservoirs, and temples. These included Ta Prohm, Preah Khan, Bayon in Angkor Thom city, and Neak Pean. |

| 1219–1243 | Indravarman II | Angkor | Son of Jayavarman VII. Lost control of Champa and western lands to Siamese Sukhothai Kingdom. |

| 1243–1295 | Jayavarman VIII | Angkor | Mongol invasion led by Kublai Khan in 1283. Also fought with Sukhothai. Built Mangalartha. He was a strong follower of Shiva and removed Buddhist influences. |

| 1295–1308 | Indravarman III | Angkor | Overthrew his father-in-law Jayavarman VIII. Made Theravada Buddhism the state religion. Received the Yuan Chinese diplomat Zhou Daguan (1296–1297). |

| 1308–1327 | Indrajayavarman | Angkor | |

| 1327–1336 | Jayavarmadiparamesvara (Jayavarman IX) | Angkor | Last known Sanskrit inscription (1327). |

| 1336–1340 | Trosok Peam | Angkor | |

| 1340–1346 | Nippean Bat | Angkor | |

| 1346–1351 | Lompong Racha | Angkor | |

| 1352–1357 | Siamese Ayutthaya invasion led by Uthong | ||

| 1357–1363 | Soryavong | Angkor | |

| 1363–1373 | Borom Reachea I | Angkor | |

| 1373–1393 | Thomma Saok | Angkor | |

| 1393 | Siamese Ayutthaya invasion led by Ramesuan | ||

| 1394–c. 1421 | In Reachea | Angkor | |

| 1405–1431 | Barom Reachea II | Chaktomuk | Abandoned Angkor (1431). |

Gallery of Temples

- Angkorian Temples in Cambodia

- Angkorian Temples in Thailand

- Angkorian Temples in Laos

- Angkorian Temples in Vietnam

See Also

In Spanish: Imperio jemer para niños

In Spanish: Imperio jemer para niños

- Post-Angkor Period

- List of kings of Cambodia – A list of Cambodian kings with their rule dates.