Ayutthaya Kingdom facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ayutthaya Kingdom

อาณาจักรอยุธยา

Anachak Ayutthaya |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1351–1767 | |||||||||||||||||||||

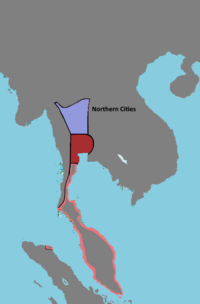

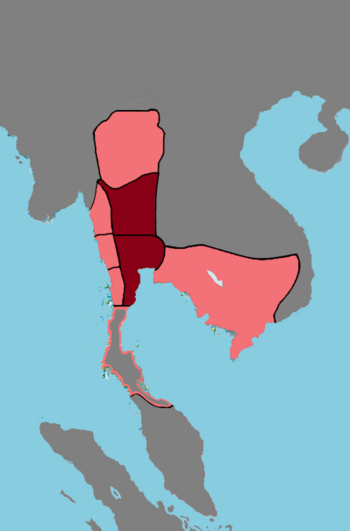

Ayutthaya and Mainland Southeast Asia in 1540. Note: Southeast Asian political borders remained relatively undefined until the modern period.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

The Ayutthaya Kingdom's sphere of influence in 1605, following the military campaigns of King Naresuan.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Majority: Theravada Buddhism Minority: Hinduism, Roman Catholic, Islam |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Mandala kingship

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1351–1369

|

Ramathibodi I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1448–c. 1488

|

Borommatrailokkanat | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1590–1605

|

Naresuan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Viceroy | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1438–1448

|

Ramesuan (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1757–1758

|

Phonphinit (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | None | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Establishment

|

4 March 1351 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• First tribute embassy to China

|

1292 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Seaborne invasions of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra

|

1290s–1490s | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Lopburi–Suphanburi rivalry

|

1370–1409 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Political merger with the Northern Cities

|

1370s–1569 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Vassal of the Taungoo dynasty

|

1564–1568, 1569–1584 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Golden Age

|

1605–1767 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Qing dynasty's revocation of private trade ban

|

1684 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Konbaung invasions

|

1759–60, 1765–67 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 April 1767 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 1600

|

~2,500,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pod duang | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

The Ayutthaya Kingdom (/ɑːˈjuːtəjə/; Thai: อยุธยา, RTGS: Ayutthaya) was a powerful kingdom in Southeast Asia. It existed from 1351 to 1767. Its capital city was Ayutthaya, located in what is now Thailand. In the 1500s, European travelers thought Ayutthaya was one of Asia's three greatest powers, along with Vijayanagar and China. Many people see the Ayutthaya Kingdom as the start of modern Thailand. Its history is a very important part of the history of Thailand.

The Ayutthaya Kingdom began when three port cities in the Chao Phraya Valley joined together. These cities were Lopburi, Suphanburi, and Ayutthaya. At first, it was a group of maritime city-states. They focused on trade and even raided other states in Southeast Asia. After about 200 years, Ayutthaya became more centralized. It grew into a major power in Asia.

From 1569 to 1584, Ayutthaya was controlled by the Taungoo dynasty of Burma. But it soon became independent again. In the 1600s and 1700s, Ayutthaya became a busy center for international trade. Its culture also grew and became very rich. King Narai (1657–1688) was famous for bringing in Persian and European influences. He even sent a special group of people to visit King Louis XIV in France in 1686. Later, the French and English left, but Chinese influence grew. This time was called a "golden age" for Thai culture. Chinese trade increased, and new ways of doing business (capitalism) started to appear. These changes continued even after Ayutthaya fell.

Ayutthaya faced problems because it didn't have a clear way to choose new kings. Also, new business ideas changed how the rich people and workers were organized. In the mid-1700s, the Burmese Konbaung dynasty attacked Ayutthaya twice, in 1759–1760 and 1765–1767. In April 1767, after a long 14-month siege, the city of Ayutthaya was completely destroyed. This ended the Ayutthaya Kingdom, which had lasted for 417 years. But Siam quickly recovered. The new capital was moved to Thonburi and then Bangkok within 15 years.

Foreigners often called Ayutthaya "Siam." But many sources say the people of Ayutthaya called themselves Tai. They called their kingdom Krung Tai (Thai: กรุงไท), which means 'Tai country'. The capital city was officially known as Krung Thep Dvaravati Si Ayutthaya (Thai: กรุงเทพทวารวดีศรีอยุธยา).

Contents

- History of the Ayutthaya Kingdom

- How Ayutthaya Was Governed

- Society and Culture

- Culture and Daily Life

- Economy and Trade

- Studying Ayutthaya's History

- Images for kids

- See also

History of the Ayutthaya Kingdom

How Ayutthaya Began

The area around the lower Chao Phraya River was divided between two kingdoms. Lopburi (Lavo) controlled the east, and Suphanburi controlled the west. The powerful Angkorian Empire also influenced this area. Some historians believe Ayutthaya was formed by joining four port cities: Lopburi, Suphanburi, Ayutthaya, and Phetchaburi.

The city of Ayutthaya likely existed before its official founding date in 1351. Archeologists have found buildings on the island of Ayutthaya from before the 1100s. Pottery from the 1270s has also been found. Some temples near Ayutthaya were built before 1351. Old Buddhist writings mention monks visiting Ayutthaya in the 1320s. They also mention a "King of Ayodhia." Some scholars think Ayutthaya was an important trading center for centuries before 1351.

Chinese records mention a Chinese official fleeing to "Xian" in 1282/83. Xian sent an embassy to China in 1292. This shows Ayutthaya was important even before its official start. Some scholars think "Xian" was an early name for Ayutthaya.

The Traditional Founding of Ayutthaya

King Uthong is traditionally said to have founded Ayutthaya on March 4, 1351. However, historians have debated this for a long time. There are many legends about who King Uthong was. Some say he was a northern Thai prince, a Chinese prince, or a Khmer noble. The only thing truly known about him from old records is the year he died.

Early Power and Trade

From the 1290s to the 1490s, Ayutthaya sent its forces down the Malay Peninsula. They demanded tribute from Malay states as far south as Singapore and Sumatra. Early Ayutthaya was a group of sea-focused states. It was more like the Malay kingdoms than inland states like Sukhothai. Old maps from Muslim and European mapmakers showed the Malay Peninsula as part of Ayutthaya.

Early Ayutthaya did not keep many written records. Its early history was likely made up later by Ayutthaya's leaders. The dates in old palace records don't always match temple records or Chinese records.

The early Ayutthaya Kingdom was held together by family ties. This was part of the mandala system. King Uthong made his son, Prince Ramesuan, the ruler of Lopburi. His brother and brother-in-law also ruled important cities. The king would appoint a prince or relative to rule a city. These cities were called Muang Look Luang (Thai: เมืองลูกหลวง). Each city ruler promised loyalty to the King of Ayutthaya. But they also kept some special rights.

Early Ayutthaya politics had rivalries between two royal families. One was the Uthong family from Lopburi, and the other was the Suphannabhum family from Suphanburi. Older stories say Ayutthaya conquered Sukhothai and Angkor. But newer ideas suggest Ayutthaya grew by joining with other cities. It slowly moved up the Chao Phraya River Basin to the Northern Cities.

A Chinese traveler named Ma Huan visited Ayutthaya in the early 1400s. He described it as a busy port town. He said men practiced fighting on water, and women managed daily life. Cities on the peninsula often complained to the Chinese court about Ayutthaya's constant attacks.

A Time of War and Change

From the 1430s to 1600, there was a lot of warfare in Southeast Asia. In 1500, the Portuguese noted Ayutthaya had 100 elephants. Fifty years later, it had 50,000 elephants! Ayutthaya began sending armies far to the west and east. In the west, it fought to control cities like Tavoy and Mergui. Trade between China and the Indian Ocean became very profitable. In the 1430s, Ayutthaya attacked Angkor. It didn't destroy the city but put a ruler in charge for a short time.

New laws under King Trailokkanat showed how important warfare had become. They offered rewards for enemies killed in battle. Elephants, guns, and hired soldiers made wars in Southeast Asia more common and deadly. By the late 1500s, problems like soldier revolts and bribery made warfare less effective. Stronger city walls also made sieges harder.

Becoming an Inland Power

The Ayutthaya Kingdom changed from a sea-focused state to an inland one. This happened during the 1400s and 1500s. It took over the Northern Cities and trade routes shifted inland towards China. King Borommatrailokkanat's rule was the peak of this change. His family had married into both northern and southern royal lines.

The Lan Na Kingdom (in modern-day Northern Thailand) fought Ayutthaya for control of the Northern Cities. This was called the Ayutthaya-Lan Na War. King Trailokkanat moved his capital to Phitsanulok. This was either because he preferred the Northern Cities or to be closer to the war. Lan Na eventually asked for peace in 1475.

Ayutthaya's power in the south was challenged by the Malacca Sultanate. Ayutthaya tried to conquer Malacca several times but failed. Malacca was protected by Ming China. The Chinese admiral Zheng He had a base there, making it too important for China to lose. Malacca grew strong under this protection. It became a major rival to Ayutthaya until the Portuguese captured it in 1511. Ayutthaya then focused on trade routes across the upper peninsula. It didn't send armies to the lower Malay States in the 1500s.

Stronger Government and Northern Lords

Ayutthaya's power now reached from the Northern Cities to the Malay Peninsula. Its main area was around the old Ayutthaya-Suphanburi-Lopburi-Phetchaburi cities. The old system of ruling cities through royal relatives was not enough for such a large area. King Trailokkanat made the government stronger and more organized with his Palatine Law of 1455. This law became Ayutthaya's constitution and was used in Siam until 1892.

The central government was run by the Chatusadom system, meaning "Four Pillars." Two Prime Ministers led the court. The Samuha Nayok handled civil matters, and the Samuha Kalahom was in charge of military affairs. Under the Samuha Nayok were four ministries. In the regions, the king sent "governors" to rule cities instead of relatives. Cities were organized into four levels, with larger cities controlling smaller ones.

Ayutthaya's growing wealth led to many fights over who would be the next king. Because there was no clear rule for choosing a new king, powerful princes or nobles often gathered their own forces. They would march on the capital to claim the throne. This led to many bloody takeovers. As the Suphanburi family became dominant, they faced military nobles from the Northern Cities. These northern lords came south for wealth in Ayutthaya. The first real fights over the throne happened in the early 1500s. The northern lords, led by Maha Thammarachathirat, became very powerful. They could even decide who became king. The Suphanburi family was finally overthrown when the Burmese captured Ayutthaya in 1569. Maha Thammarachathirat was then placed on the throne by the Burmese.

The 1400s also changed how Ayutthaya saw itself. King Trailokkanat had a coronation ceremony in the 1460s, the first in Ayutthaya's history. Before the 1400s, Ayutthaya's palaces and temples were not as grand as those in Sukhothai or Phitsanulok. But by the early 1500s, Ayutthaya had magnificent temples and palaces. It also had many states that paid tribute to it.

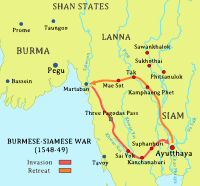

Wars with Burma

Starting in the mid-1500s, the Taungoo dynasty of Burma attacked Ayutthaya many times. The first war (1547–1549) ended with a failed Burmese siege of Ayutthaya. A second siege (1563–1564), led by King Bayinnaung, forced King Maha Chakkraphat to give up in 1564. The royal family was taken to Burma. The king's second son, Mahinthrathirat, was made a puppet king. In 1568, Mahinthrathirat rebelled. The third siege in 1569 captured Ayutthaya. Bayinnaung then made Maha Thammarachathirat his puppet king. This started the Sukhothai dynasty in Ayutthaya.

In May 1584, King Naresuan (son of Maha Thammarachathirat) declared Ayutthaya's independence. This led to more Burmese invasions. The Siamese fought them off. In 1593, during the fourth siege, Naresuan famously defeated the Burmese heir in an elephant duel. This victory is celebrated every year on January 18 as Royal Thai Armed Forces day. Later, the Siamese invaded Burma. They took over areas like Tanintharyi province. In 1599, the Siamese attacked Pegu but were driven out by Burmese rebels.

In 1613, King Anaukpetlun reunited Burma. The Burmese then invaded Siamese-held lands and took Tavoy. In 1614, they invaded Lan Na, which was controlled by Ayutthaya. Fighting continued until 1618, when a treaty ended the conflict. Burma gained control of Lan Na, and Ayutthaya kept southern Tanintharyi.

Peace and Global Trade

Around 1600, the wars stopped, and a long period of peace and trade began. This started with King Ekathotsorot's rule. The Portuguese and Dutch had conquered Malacca. This made Asian traders avoid Malacca by using a land route across the middle of the peninsula, which Ayutthaya controlled. This was a time of great empires like the Ottomans, Safavids, Mughals, Ming, Qing China, and Tokugawa Japan. Ayutthaya became a rich middleman for trade between these global empires. Kings and nobles focused on trade and competing for the throne.

During this time, the king gained almost complete control over all money coming into the kingdom. This allowed him to build new temples and palaces. He also sponsored ceremonies and made the monarchy seem more mysterious and powerful. The king could appoint governors and ministers. This made the throne even more valuable. Foreigners often became important officials in Ayutthaya because they had no local connections.

Changes in Royal Power

In 1605, King Naresuan died, leaving a much larger kingdom to his younger brother, Ekathotsarot. His reign was stable. Ayutthaya had more contact with other countries, especially the Dutch Republic, Portugal, and Japan. Many foreigners worked in Siam's government and military. Japanese traders and soldiers, led by Yamada Nagamasa, had a lot of influence with the king.

Ekathotsarot died in 1610/11. His son, Si Saowaphak, became king but was not very effective. He was kidnapped by Japanese merchants and later murdered. After this, Songtham, another son of Ekathotsarot, became king.

Songtham brought back stability to Ayutthaya. He focused on building religious sites, like a great temple at Wat Phra Phutthabat. In foreign policy, Songtham lost control of Lan Na, Cambodia, and Tavoy. He expelled the Portuguese. But he expanded trade with the English and French. He also kept Yamada Nagamasa and his Japanese soldiers as his royal guards.

When Songtham was dying, there was conflict over who would be the next king. His brother, Prince Sisin, and his son, Prince Chetthathirat, both had supporters. King Songtham asked his powerful cousin, Prasat Thong, to help his son become king. When Songtham died in 1628, Prasat Thong used his alliance with Yamada Nagamasa's soldiers. He removed and executed everyone who supported Prince Sisin. Prasat Thong soon became more powerful than the new king, Chetthathirat. He then staged a coup, removing and executing Chetthathirat. He put Chetthathirat's younger brother, Athittayawong, on the throne, planning to control him.

But many in the Thai court did not like having two leaders. Prasat Thong already ruled Siam in all but name. So, he had the child king removed and executed in 1629. This way, Prasat Thong took over the kingdom completely. He ended the Sukhothai dynasty. Many of Prasat Thong's former allies left him. He assassinated Yamada Nagamasa in 1630, who had opposed his takeover. He then banished all remaining Japanese from Siam. This ended Japan's formal relationship with Ayutthaya.

Persian and French Influences

When King Prasat Thong died in 1656, his eldest son, Chai, became king. But he was quickly removed and executed by his uncle, Si Suthammaracha. Si Suthammaracha was then defeated by his nephew, Narai. Narai became a stable king with support from foreign groups. These included Persian, Dutch, and Japanese soldiers. King Narai's time was known for Siam's openness to the world. Foreign trade brought luxury goods and new weapons. In the mid-1600s, Ayutthaya became very rich under King Narai.

In 1662, war broke out again between Burma and Ayutthaya. King Narai tried to take advantage of problems in Burma to control Lan Na. Fighting continued for two years. Narai captured Tavoy and Martaban for a time. But he ran out of supplies and returned to Siam.

While trade was booming, Narai's reign also had social problems. This was due to conflicts between the Dutch, French, and English trading companies. They were all very active in Siam because it was a trade center. Narai preferred relations with the French. He was worried about the growing Dutch and English colonies nearby. Soon, Narai welcomed French Jesuits to his court. He sought closer ties with France and the Vatican. His many diplomatic missions to faraway lands are famous achievements of his reign. Narai also leased the ports of Bangkok and Mergui to the French. He had French generals train his army and build European-style forts. During this time, Narai moved his capital from Ayutthaya to a new palace in Lopburi.

As more Catholics came to Siam, and more French forts were built, some Siamese nobles and Buddhist monks became unhappy. They disliked the special treatment the French received. This anger was especially aimed at Constantine Phaulkon. He was a Greek adventurer and a Catholic. He had become Narai's Prime Minister and chief advisor on foreign affairs. Much of the trouble was religious. French Jesuits openly tried to convert Narai and the royal family to Catholicism.

Narai was also approached by Muslim Persians, Chams, and Makassars in his court. The Makassars even started a failed revolt in 1686 to replace Narai with a Muslim king. While the anti-foreign group was mainly worried about Catholic influence, Narai was also interested in Islam. He did not want to fully convert to either religion.

A group led by Narai's elephant commander, Phetracha, planned to overthrow Narai. When the king became very ill in May 1688, Phetracha had him arrested. He also arrested Phaulkon and many royal family members. They were all killed, except Narai, who died in prison in July. With the king and his heirs gone, Phetracha took the throne. He crowned himself King of Ayutthaya on August 1.

King Phetracha quickly took Mergui back from French control. He then started the Siege of Bangkok, which made the French leave Siam. But Phetracha's rule was not stable. Many governors refused to accept him as king. Supporters of the late Narai continued to rebel for many years. The biggest change was Phetracha's decision to stop Narai's foreign embassies. King Phetracha closed Thailand to almost all European contact, except with the Dutch.

Late Ayutthaya Period

Continued Prosperity and Chinese Connections

Even though most Europeans left Ayutthaya, their trade was small compared to Ayutthaya's trade with China and the Indian Ocean. Some historians used to think Siam's isolation after 1688 led to its decline. But newer research shows that the 1700s were actually Ayutthaya's most prosperous time. This was especially due to trade with Qing China. China's population grew, and it had rice shortages. So, China eagerly imported rice from Ayutthaya.

During the Late Ayutthaya Period (1688–1767), the Chinese population in Ayutthaya may have tripled to 30,000 people. The Chinese were key to Ayutthaya's economy in its last 100 years. They also helped Siam recover quickly after the Burmese invasions of the 1760s. Later Thai kings, like Taksin and Rama I, had close ties to this Chinese-Siamese community.

Succession Fights and Corruption

Between 1600 and 1767, almost every time a new king was chosen, it led to a small civil war in the capital. The throne became so powerful and rich that many royals wanted to seize it. An Ayutthaya noble in the 1700s sadly noted that many court officials and generals were killed in these power struggles. The last king, Ekkathat, and his brother, Uthumphon, even undermined Prince Thammathibet. He was the chosen heir to their father, King Borommakot. Prince Thammathibet was executed for alleged crimes.

Corruption was widespread because of the economic prosperity. People bought positions and bribed officials for political jobs.

New Ideas and Commoners' Rise

The arrival of many Chinese farmers in Siam in the 1700s brought new economic ideas. The past 150 years of growth encouraged common people to escape government control. They became peasant farmers in the countryside to earn wealth. People also avoided the government system by becoming monks or fleeing into the wilderness.

A new group of people appeared in late Ayutthaya records: phrai mangmi, or rich "serfs."

From 1688 onwards, there were more and more revolts by common people. The 1688 revolt against French Catholicism was new for Ayutthaya. The revolts of 1688 also marked the start of a kind of early nationalism. People began to form a sense of a Siamese Buddhist identity. However, Ayutthaya kings only sometimes saw themselves as protectors of "the kingdom, people, and Buddhism." This idea fully developed later, after the traumatic destruction of the Siamese state in 1767.

Nobility and Buddhism

The 150 years of prosperity brought great wealth to Ayutthaya's elite. They created plays, held grand celebrations, and were given royal titles. These things were once only for royalty.

Kings and nobles now competed to control the decreasing number of workers. Repeated laws about controlling labor showed that the elite were failing to control the people.

The problems caused by increasing wealth led the Ayutthaya nobility to reform Buddhism. They hoped it would bring new social order. King Borommakot (1733-1758) symbolized this. He was seen as a very religious king. He built and restored many temples, changing Ayutthaya's skyline. In 1753, he sent two Siamese monks to Sri Lanka to help reform Theravada Buddhism there.

It would take until the early Rattanakosin period for the surviving Ayutthaya nobility to fully reform Buddhism. This created a strong link between the Siamese monarchy and Buddhism that continues today.

Military and Political Situation to 1759

Between 1600 and 1759, wars were less frequent than before. King Narai tried but failed to capture Chiang Mai in the 1650s and 1660s. Ayutthaya also fought with Vietnamese rulers for control of Cambodia starting around 1715. But Ayutthaya and Burma generally had peaceful relations and exchanged ambassadors in the 1600s.

Ayutthaya's military organization stayed mostly the same for 150 years. It still relied heavily on hired soldiers. It failed to create an elite military class like the Samurai in Japan. Perhaps Ayutthaya kings purposely prevented such a group from forming to avoid challenges to their power. The city of Ayutthaya also relied on the wet season monsoons. These made the city impossible to besiege for six months a year. Ayutthaya had a huge collection of cannons and weapons. The Burmese were amazed by them when they took Ayutthaya in 1767. However, Ayutthaya lacked enough men to use these weapons. The old system of forced labor was failing. More people were escaping it due to new economic opportunities.

The Fall of Ayutthaya

In the 1740s, Burma's Taungoo dynasty collapsed due to a revolt. This led to the new, militaristic Konbaung dynasty in Upper Burma. By the mid-1750s, they had reunited Burma.

The first Burmese invasion in 1759–1760 failed to capture Ayutthaya. But the Konbaung dynasty successfully took the port city of Tavoy.

In 1765, a Burmese army of 40,000 men invaded Ayutthaya from the north and west. Major towns quickly surrendered and did not help defend the capital. However, many people in Ayutthaya, including foreigners, fought bravely for a year and a half. After a 14-month siege, the city of Ayutthaya fell on April 7, 1767. It was completely destroyed. Ayutthaya's art, libraries, and historical records were almost all lost. The Burmese brought the Ayutthaya Kingdom to an end. Historians say hundreds of thousands may have died during the invasion. Many people were taken by the Burmese or fled into the forests. Objects were taken back to Burma. Anything that couldn't be moved was burned by Burmese soldiers.

Historians Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit say the fall of Ayutthaya was a "failure of defense" and a "failure of dealing with rising wealth." By 1767, Ayutthaya was a rich prize that many kingdoms wanted. In that time, wars were fought between kings, not based on ethnic groups. Some Siamese even joined the Burmese in destroying Ayutthaya, including the governor of Suphanburi. Ayutthaya nobles taken by the Burmese settled well in the Burmese court. As historian Nidhi Eoseewong said, the "kingdom fell even before the walls of Ayutthaya fell."

What Happened Next

Within weeks, most Burmese forces returned to Burma. They were also fighting a big war with China since 1765. The only Burmese soldiers left in Siam were a few thousand outside the former capital. Many of them were also pulled back as the situation in Burma worsened.

With most Burmese gone, the country fell into chaos. Ayutthaya's government was completely destroyed. Provinces declared independence under generals, monks, and royal family members.

However, Ayutthaya had centuries of political and economic development. This was hard to destroy completely. One general, Phraya Taksin, began to reunite Siam. He was the former governor of Tak and was of Siamese-Chinese descent. He gathered his forces and retook the ruined capital of Ayutthaya from the Burmese in June 1767. He used his connections to the Chinese community for resources and political support. He then established a new capital at Thonburi, across the Chao Phraya River from modern Bangkok. Taksin became King. By 1771, he had reunited Siam (except for Mergui and Tenasserim) and defeated all local warlords. The conflict between Burma and Siam continued for another 50 years. This left large areas of Siam empty, including the Northern Cities and Phitsanulok.

The palaces and temples of Ayutthaya were reduced to "heaps of ruins and ashes." A Danish visitor in 1779 described the city as a "terrible sight," covered in plants and inhabited by elephants and tigers. But the city was resettled soon after. Old Ayutthaya temples were used for festivals. Later kings of Thailand (from the Rattanakosin period) took apart many of the ruins that survived the Burmese attack. They used the bricks to build the new capital at Bangkok. This was for symbolic reasons, showing Bangkok as Ayutthaya's successor. It was also practical, as there wasn't enough time to build a new capital from scratch during early Rattanakosin.

How Ayutthaya Was Governed

The Kings of Ayutthaya

In its early days, Ayutthaya's rulers were leaders of a port city. A Chinese traveler in the 1400s described the king as wearing gold-trimmed pants. He rode an elephant to inspect the city and lived in a simple home. Early Ayutthaya rulers had to balance their power with that of their vassal cities. As Ayutthaya grew and took over the Northern Cities, its rulers became more powerful. They also became richer through trade in the 1600s. They used their wealth to show their power, adding old rituals and symbols to the monarchy.

From the 1600s onwards, Ayutthaya's kings were absolute monarchs. This means they had complete power. They were seen as semi-religious figures. Their authority came from Hindu and Buddhist beliefs. The king of Sukhothai was seen as a father figure to his people. He would listen to anyone who rang a bell at the palace gate.

But in Ayutthaya, this fatherly image changed. The king was seen as a chakkraphat (universal ruler). He was believed to be an avatar of Vishnu, a Hindu god. In Buddhism, the king was a righteous ruler (dharmaraja). He followed the teachings of Gautama Buddha and worked for his people's well-being.

The kings' official names reflected these religions. They were seen as incarnations of Hindu gods like Indra, Shiva, or Vishnu (Rama). The coronation ceremony was led by brahmins. This was because the Hindu god Shiva was "lord of the universe." The king's duty was to protect his people and defeat evil.

In Buddhism, the king was also believed to be a bodhisattva. One important duty was to build temples or Buddha statues. These symbolized prosperity and peace.

Locally, the king was also called "The Lord of the Land." A special language, Rachasap ('royal language'), was used when speaking to or about royalty. In Ayutthaya, the king gave control over land to his subjects. This was based on the sakdina system, created by King Borommatrailokkanat. This system was similar to, but not the same as, feudalism. In feudalism, the king does not own all the land. A French visitor in 1685 wrote that "the king has absolute power. He is truly the god of the Siamese: no-one dares to utter his name." A Dutch writer in the 1600s said the King of Siam was "honoured and worshipped by his subjects second to god." The king issued laws and orders. Sometimes, he was also the highest judge for serious crimes.

King Borommatrailokkanat also created the position of uparaja, or 'viceroy'. This was usually the king's eldest son or full brother. It was meant to make choosing the next king easier. But in reality, there was often conflict between the king and the uparaja. This led to frequent disputes over who would rule next. The king's power had limits. His authority depended on his age and supporters. Without supporters, bloody takeovers happened often. The most powerful people in the capital were usually generals or the Minister of Military Department. In Ayutthaya's last century, bloody fights among princes and generals for the throne were common.

Except for King Naresuan's succession by Ekathotsarot in 1605, the way to become king in the 1600s was through battle. European visitors tried to understand the rules for succession. They noted that the dead king's younger brother often became king. But this rule was not written down. The ruling king often gave the title of uparaja to his preferred successor. But in reality, it was a "survival of the fittest" process. Any male royal could claim the throne and win by defeating rivals. Nobles, foreign merchants, and foreign soldiers often supported different candidates. They hoped to benefit from the outcome of these power struggles.

Mandala System of Rule

Ayutthaya's political system was a mandala system. This was common in Southeast Asian kingdoms before the 1800s. In the 1600s, Ayutthaya kings often appointed non-locals as governors of towns. This was to prevent local nobles from becoming too powerful. By the end of the Ayutthaya period, the capital had strong control over cities in the lower Chao Phraya plain. But its control became looser the further away cities were. A Thai historian noted that Ayutthaya was not a strong, centralized state. The power of provincial governors was never fully removed.

Society and Culture

Social Classes

King Borommatrailokkanat's reforms (1448–1488) placed the king at the top of a very structured social system. Society was organized into village communities of extended families. The village headman held land for the community. Peasants could use the land as long as they farmed it. Lords gradually became court officials and rulers of smaller cities. The king was seen as a god on Earth, an incarnation of Shiva or Vishnu. Buddhist beliefs also saw the king as a bodhisattva. This idea of a divine king lasted into the 1700s, though its religious meaning lessened over time.

Ranking in Society

With plenty of land, the kingdom needed enough people for farming and defense. Ayutthaya's rise involved constant warfare. Since no side had better technology, army size often decided battles. After winning, Ayutthaya would bring conquered people back to its land. They were then absorbed into the workforce. King Ramathibodi II (1491–1529) created a forced labor system called corvée. Every free man had to register as a phrai (servant) with local lords, chao nai. In wartime, male phrai had to join the army. Above the phrai was a nai, who was responsible for military service, public works, and working on the land of the official they were assigned to. Phrai Suay could pay a tax instead of working. If a phrai disliked their forced labor, they could sell themselves as a that (slave) to another lord. This lord would pay a fee for the lost labor. Up to one-third of the workforce until the 1800s were phrai.

Wealth, status, and political power were connected. The king gave rice fields to officials, governors, and military commanders. This was payment for their service, based on the sakdina system. The size of an official's land depended on how many commoners or phrai they could command. The number of workers a headman or official could command showed their status and wealth. The king, at the top, theoretically commanded the most phrai, called phrai luang ('royal servants'). These phrai luang paid taxes, served in the royal army, and worked on royal lands.

However, the army relied on nai, or mun nai, who commanded their own phrai som (subjects). These officials had to obey the king's command during war. Officials became key figures in politics. At least two officials staged coups and took the throne. Bloody struggles between the king and his officials, followed by purges, were common.

King Trailok, in the early 1500s, set specific amounts of land and phrai for royal officials at each level. This shaped the country's social structure until salaries for officials were introduced in the 1800s.

| Social class | Description |

|---|---|

| munnai | Rich officials in the capital and other centers who did not pay taxes. |

| phrai luang | Royal servants who worked for the king for a set time each year (maybe six months). They usually could not leave their village unless for work or military service. |

| phrai som | Common people who did not have to work for the king. There were many more of them than phrai luang. |

Outside this system were the sangha (Buddhist monks), which anyone could join, and the overseas Chinese. Temples became centers for Thai education and culture. During this time, Chinese people began settling in Thailand. They soon gained control over the country's economy.

The Chinese did not have to do forced labor. So, they could move freely and trade. By the 1500s, the Chinese controlled Ayutthaya's internal trade. They also held important positions in government and military. Most Chinese men married Thai women, as few Chinese women came with them.

King Uthong created a legal code called Dharmaśāstra. It was based on Hindu ideas and old Thai customs. This law was used in Thailand until the late 1800s. A government system with ranked officials was also introduced. Society was organized in a similar way. However, the caste system was not adopted.

The 1500s saw the rise of Burma. Burma took over Chiang Mai in the Burmese-Siamese War of 1563–1564. In 1569, Burmese forces, joined by Thai rebels, captured Ayutthaya. They took the entire royal family to Burma. Thammarachathirat (1569–1590), a Thai governor who helped the Burmese, was made a puppet king. Thai independence was restored by his son, King Naresuan (1590–1605). He fought the Burmese and drove them out by 1600.

To prevent another betrayal, Naresuan united the country's government directly under the royal court in Ayutthaya. He stopped appointing royal princes to govern provinces. Instead, he assigned court officials who followed the king's policies. Royal princes were kept in the capital. Their power struggles continued, but under the king's watch.

To control the new governors, Naresuan declared that all free men who had to do phrai service would become phrai luang. This meant they were directly tied to the king. The king then allowed his officials to use their services. This gave the king theoretical control over all manpower. The idea grew that since the king owned everyone's services, he also owned all the land. Ministerial jobs and governorships, along with their sakdina ranks, were usually passed down in families. These families were often connected to the king by marriage. Kings often used marriage to form alliances with powerful families. This custom continued into the 1800s. As a result, kings often had dozens of wives.

Even with Naresuan's reforms, the royal government's power was unstable for the next 150 years. The king's power outside the capital, though absolute in theory, was limited by a weak government system. The central government and king had little influence far from the capital. When war with the Burmese broke out in the late 1700s, provinces easily abandoned the capital. Since troops were not easily gathered to defend the capital, Ayutthaya could not stand against the Burmese.

Military Power

Ayutthaya's military was the start of the Royal Thai Army. The army had a small standing force of a few thousand soldiers. These defended the capital and the palace. There was also a much larger wartime army based on conscription. Conscription used the Phrai system. Local chiefs had to provide a certain number of men from their area based on population during wartime. This basic military system stayed mostly the same until the early Rattanakosin period.

Infantry soldiers mainly used swords, spears, and bows and arrows. Cavalry (soldiers on horses) and elephantry (soldiers on war elephants) supported the infantry.

Ayutthaya's Territory

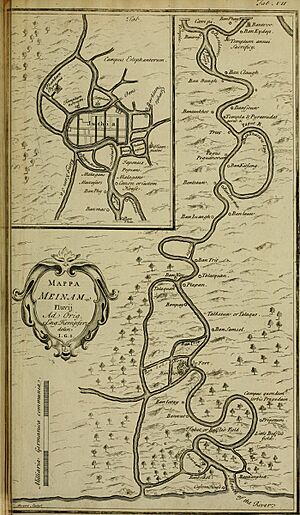

According to a French source, Ayutthaya in the 1700s included major cities like Martaban, Nakhon Sri Thammarat, Tenasserim, Phuket Island, and Songkhla. Its tributary states were Patani, Pahang, Perak, Kedah, and Malacca.

Especially in the South, Ayutthaya's claims were often challenged by Malay sultanates. This led to military expeditions in the 1600s and 1700s to control rebellious sultanates. A famous example is King Narai's military expedition to the Sultanate of Singora in 1680.

Culture and Daily Life

Population and Society

For its entire history, the Ayutthaya Kingdom was mostly run by a small group of nobles. The rest of the population were serfs (phrai). This was similar to the old social system in France or feudalism in Europe. A social ladder existed during wartime. Especially in the late Ayutthaya period, rich commoners began to challenge the social order. This was due to the kingdom's economic success in its last 150 years.

Historian Chris Baker says that Ayutthaya's peasants often traveled to farm. They lived in crowded areas along canals leading to Ayutthaya and other cities. They made homemade goods and textiles for international trade.

Languages Spoken

The Siamese (Thai) language was first spoken only by Ayutthaya's elite. But it slowly spread to all social classes. By the Late Ayutthaya period (1688-1767), it was widely spoken. However, the Mon language was common among everyday people in the Chao Phraya delta until around 1515. The Khmer language was an important language in the early Ayutthaya court. It was later replaced by Siamese, but ethnic Khmers in Ayutthaya still spoke it. Many types of Chinese were spoken, as Chinese people became a large minority in the late Ayutthaya period.

Other minority languages spoken in the kingdom included Malay, Persian, Japanese, Cham, Dutch, and Portuguese.

Religion and Beliefs

Ayutthaya's main religion was Theravada Buddhism. However, many parts of the political and social system came from Hindu scriptures. Brahmin priests performed many ceremonies. Some areas also practiced Mahayana Buddhism and Islam. A few small areas converted to Roman Catholicism after French missionaries arrived in the 1600s. Mahayana and Tantric practices also influenced Theravada Buddhism, creating a tradition called Tantric Theravada.

The natural world was also home to many spirits, part of the Satsana Phi (spirit worship). Phi (Thai: ผี) are spirits of buildings, places, or nature. They can also be helpful ancestral spirits or harmful ones. Phi that are guardian deities of places or towns are celebrated with festivals and food offerings. These spirits are important in Thai folklore.

People believed Phi influenced nature, including human illness. So, the baci became important for people's identity and health. Spirit houses were a folk custom to keep balance with the natural and supernatural worlds. Astrology was also vital for understanding these worlds. It became an important way to enforce social rules and customs.

Arts and Performances

The myths and epic stories of Ramakien gave the Siamese many ideas for plays. The royal court of Ayutthaya developed classical dramatic forms called khon (Thai: โขน) and lakhon (Thai: ละคร). Ramakien was very important in shaping these arts. During the Ayutthaya period, khon was a special performance only for nobles. Thai drama and classical dance later spread throughout Southeast Asia. They influenced high-culture art in Burma, Cambodia, and Laos.

Historical records show that Thai stage plays were highly developed by the 1600s. King Louis XIV of France had diplomatic ties with Ayutthaya's King Narai. In 1687, the French diplomat Simon de la Loubère visited Siam. He carefully observed the classical 17th-century Thai theater. He described a khon performance with an epic battle scene in great detail.

La Loubère noted that khon was a masked dance with weapons. The dancers moved wildly but also spoke. Many masks were scary, showing monsters or devils. He also described lakhon as a long poem, sung by actors, lasting three days. Rabam was a slow, graceful dance for men and women.

He also described the costumes. Dancers in Rabam and Khon wore gilded paper hats. These hats were tall and pointed, like official caps. They had fake jewels and gilded wooden pendants.

La Loubère also saw muay Thai and muay Laos. He noted they looked similar, using fists and elbows to fight. But the hand-wrapping techniques were different. Muay Thai from the Ayutthaya period (known as Muay Boran) greatly influenced the modern sport of Muay Thai.

The influence of Thai art and culture from Ayutthaya on neighboring countries was clear. James Low, a British scholar, noted in the early Rattanakosin Era: "The Siamese have attained to a considerable degree of perfection in dramatic exhibitions – and are in this respect envied by their neighbours the Burmans, Laos, and Cambojans who all employ Siamese actors when they can be got."

Krabi-krabong is a form of sword fighting developed in Ayutthaya. It is now a key part of traditional Thai culture. Wat Phutthaisawan, an ancient temple in Ayutthaya, is considered its birthplace.

Literature and Stories

Ayutthaya was rich in literary works. Even after the city was destroyed in 1767, many Thai literary masterpieces survived. However, Ayutthayan literature was mostly poetry. Prose works were used for legal matters, state records, and historical accounts. So, there are many epic poems in Thai. Thai poetry was based on native forms like rai, khlong, kap, and klon. Some of these forms, like khlong, were shared among Tai language speakers even before Siam existed.

Indian Influence on Thai Language

Through Buddhist and Hindu influence, many new poetic styles came from Sri Lanka. Since Thai is a single-syllable language, many words from Sanskrit, Tamil, and Pali were needed for these classical styles. This process sped up during King Borommatrailokkanat's reign (1448–1488). He reformed Siam's government, turning it into an empire under the mandala system. The new system needed a new, grander language for the nobles. This literary influence changed the Thai language. It made it different from other Tai languages by adding many Sanskrit and Pali words. It also required Thais to develop a writing system that kept the original spelling of Sanskrit words for literature. By the 1400s, the Thai language had become unique, with a growing literary identity for a new nation. This allowed Thai poets to write in different styles, from playful rhymes to romantic klong and formal chan poems. Thai poets experimented with these forms, creating new "hybrid" poems. This made Thais very skilled in poetry. However, to truly master this, a lot of classical education in Pali was needed. This made poetry a job mostly for nobles. But a 17th-century textbook, Jindamanee, shows that scribes and common men were also encouraged to learn basic Pali and Sanskrit to get better jobs.

The Ramakien Epic

Most Southeast Asian countries share a culture influenced by India. So, Thai literature was heavily influenced by Indian culture and Buddhist-Hindu ideas from its beginning in the 1200s. Thailand's national epic is a version of the Rama-Pandita story. It is called the Ramakien. It was translated from Pali and rewritten in Thai verses. The Ramayana epic is important in Thailand because Thais adopted the Hindu idea of kingship, as shown by Rama. The Siamese capital, Ayutthaya, was named after the holy city of Ayodhya, Rama's city. Thai kings of the current dynasty, from Rama VI onwards, are called "Rama" today.

Many versions of the Ramakien epic were lost when Ayutthaya was destroyed in 1767. Three versions still exist today. One was prepared under King Rama I's supervision and partly written by him. His son, Rama II, rewrote some parts for khon drama. The main differences from the original are a bigger role for the monkey god Hanuman and a happy ending. Many popular poems among Thai nobles are also based on Indian stories. One famous example is Anirut Kham Chan, based on the ancient Indian story of Prince Anirudha.

Khun Chang Khun Phaen: A Thai Folk Epic

In the Ayutthaya period, folk tales were also popular. One of the most famous is Khun Chang Khun Phaen (Thai: ขุนช้างขุนแผน), often called "Khun Phaen" in Thailand. It mixes romantic comedy and heroic adventures, ending sadly. The epic of Khun Chang Khun Phaen (KCKP) is about Khun Phaen, a Thai general with magic powers who served the King of Ayutthaya. It also tells of his love triangle with Khun Chang and a beautiful girl named Wan-Thong. KCKP, like other stories passed down orally, changed over time. It started as a recitation called sepha around 1600. Thai storytellers added more parts and details as time went on. By the late Ayutthaya Kingdom, it became a long epic poem of about 20,000 lines. The version today is written in klon meter and is called nithan Kham Klon (Thai: นิทanคำกลอน), meaning a 'poetic tale'.

Architecture and Buildings

Ayutthaya's Buddhist temples fit into two main types: the stupa-style solid temple and the prang-style (Thai: ปรางค์). Prangs can also be found in Sukhothai, Lopburi, and Bangkok. They usually range from 15 to 40 meters tall and look like a towering corn cob.

Prangs represent Mount Meru, a sacred mountain in Hindu and Buddhist beliefs. In Thailand, Buddha relics were often placed in a vault inside these structures. This showed the belief that the Buddha was a very important being who found enlightenment and showed others the way.

Important Historical Sites

| Name | Picture | Built | Sponsor(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan Palace, Phitsanulok |  |

Built during the Sukhothai period (1238–1438) | King Maha Thammaracha I of Sukhothai | Former royal home for Ayutthaya's Front Palaces, including King Trailokanat and King Naresuan. Used from the Sukhothai period until Naresuan left it. |

| Chedi Phukhao Thong |  |

1587 (rebuilt in 1744) | Prince (later King) Naresuan King Borommakot |

Built to remember a battle victory after Ayutthaya became free from Burma in 1584. |

| Elephant Kraal Pavilion (พระที่นั่งเพนียด) |  |

16th century | A royal elephant pen used by Ayutthaya kings. It is one of the few still existing in Thailand and is used as an elephant camp today. | |

| Front Palace, Ayutthaya |  |

Main home of Ayutthaya's Front Palaces. Restored by King Mongkut. Now holds the Chan Kasem National Museum. | ||

| King Narai's Palace, Lopburi |  |

1666 | King Narai | King Narai's palace from 1666 until he died in 1688. |

| Prasat Nakhon Luang |  |

1631 | King Prasat Thong | Mostly rebuilt during the reign of King Rama V. |

| Wat Chai Watthanaram |  |

1630 | King Prasat Thong | |

| Wat Ko Kaew Suttharam, Phetchaburi |  |

1734 | King Borommakot | One of the best examples of 18th-century Ayutthaya temple murals. |

| Wat Kudi Dao |  |

Before 1711 | Prince, later King Borommakot | A good example of 18th-century Late Ayutthaya architecture. Partially restored. |

| Wat Mahathat |  |

1374 | King Borommarachathirat I | |

| Wat Na Phra Men |  |

1503 | King Ramathibodi II | One of the best preserved Ayutthaya temples. It survived the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767. Restored during the reign of Rama III. |

| Wat Phanan Choeng |  |

1324 | Built 27 years before the founding of Ayutthaya. It is a respected temple still in use. | |

| Wat Phra Ram |  |

1369 | King Ramesuan | |

| Wat Phra Phutthabat (วัดพระพุทธบาท), Saraburi |

|

1624 | King Songtham | A pilgrimage site in Thailand even today. |

| Wat Phra Si Sanphet |  |

1351 | King Ramathibodi I | |

| Wat Phutthaisawan |  |

Before 1351 | King Ramathibodi I | Built before Ayutthaya was founded. It is the birthplace of Thai krabi-krabong sword fighting. |

| Wat Ratchaburana |  |

1424 | King Borommarachathirat II | |

| Wat Thammikarat |  |

Before 1351 | ||

| Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon |  |

1357 | King Ramathibodi I | |

| Wihan Phra Mongkhon Bophit |  |

Heavily renovated during the reign of King Borommakot (r. 1733–1758) | King Borommakot | Heavily damaged by the Burmese attack in 1767. Its current look is mostly from King Borommakot's renovations in the 1700s. It was largely rebuilt in the mid-1900s. |

Daily Life in Ayutthaya

Clothing Styles

There were three main clothing styles in the Ayutthaya period. Each style depended on a person's social class.

- Court clothing (worn by the king, queen, concubines, and senior government officials):

-

- Men: The king wore a mongkut (Thai: มงกุฎ), a special crown. He wore a round Mandarin collar shirt with a khrui (a type of robe) and chong kben (Thai: โจงกระเบน), which were like trousers.

- Court officers wore a lomphok (headgear), khrui, and chong kben.

- Women: The queen wore a chada (Thai: ชฎา), a type of crown. She wore a sabai (Thai: สไบ), a cloth wrapped over one shoulder, and a pha nung (Thai: ผ้านุ่ง), like a skirt.

- Concubines had long hair and wore sabai and pha nung.

- Nobles (rich citizens):

-

- Men: Wore a mandarin collar shirt, a mahadthai hairstyle (Thai: ทรงมหาดไทย), and chong kben.

- Women: Wore the sabai and pha nung.

- Villagers:

-

- Men: Wore a loincloth, had a bare chest, a mahadthai hairstyle, and sometimes wore a sarong or chong kben.

- Women: Wore the sabai and pha nung.

Economy and Trade

The Thai people always had plenty of food. Farmers grew rice for themselves and to pay taxes. Any extra rice was used to support religious places. From the 1200s to the 1400s, Thai rice farming changed. In the highlands, where rain was controlled by irrigation, Thais grew sticky rice. This is still a main food in the north and northeast. But in the Chao Phraya floodplain, farmers started growing "floating rice." This was a thin, non-sticky grain from Bengal. It grew fast enough to keep up with rising water levels in the lowlands.

This new rice grew easily and in large amounts. It created a surplus that could be sold cheaply to other countries. Ayutthaya, at the southern end of the floodplain, became the center of economic activity. With royal support, forced labor dug canals. Rice was brought from the fields to the king's ships to be exported to China. This process also reclaimed and farmed the Chao Phraya delta. This area was once considered unsuitable for living. Traditionally, the king performed a religious ceremony to bless the rice planting.

Even though rice was plentiful, rice exports were sometimes banned. This happened during famines caused by natural disasters or war. Rice was usually traded for luxury goods and weapons from Westerners. But rice farming was mainly for local use, and rice export was not always reliable.

Currency Used

Ayutthaya officially used cowrie shells, prakab (baked clay coins), and pod duang as money. Pod duang became the main form of money from the early 1200s until the reign of King Chulalongkorn.

Ayutthaya as a Global Trading Port

Trade with Europeans was very active in the 1600s. European merchants traded their goods, mostly modern weapons like rifles and cannons. In return, they received local products from the jungle, such as sappan wood, deerskin, and rice. Tomé Pires, a Portuguese traveler, wrote in the 1500s that Ayutthaya, or Odia, was "rich in good merchandise." Most foreign merchants coming to Ayutthaya were European and Chinese. They were taxed by the authorities. The kingdom had plenty of rice, salt, dried fish, arrack (an alcoholic drink), and vegetables.

Trade with foreigners, mainly the Dutch, was highest in the 1600s. Ayutthaya became a major destination for merchants from China and Japan. It was clear that foreigners were becoming involved in the kingdom's politics. Ayutthaya's kings hired foreign soldiers. These soldiers sometimes joined wars against the kingdom's enemies. However, after the French were removed in the late 1600s, the main traders with Ayutthaya were the Chinese. The Dutch from the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) were still active. Ayutthaya's economy declined quickly in the 1700s. It completely collapsed after the Burmese invasion in 1767.

Contact with Western Countries

In 1511, after conquering Malacca, the Portuguese sent a diplomatic mission to King Ramathibodi II of Ayutthaya. They formed friendly relations between Portugal and Siam. They returned with a Siamese envoy who carried gifts and letters to the King of Portugal. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to visit the country. Portuguese soldiers also played a big role in King Chairachathirat's invasion of Lanna in 1539. Portuguese soldiers were seen as a respected fighting force for Ayutthaya throughout its history. Five years after this first contact, Ayutthaya and Portugal signed a treaty. It allowed the Portuguese to trade in the kingdom. A similar treaty in 1592 gave the Dutch a special position in the rice trade.

Foreigners were warmly welcomed at the court of Narai (1657–1688). He was a king with a global outlook but was careful about outside influence. Important trade ties were made with Japan. Dutch and English trading companies were allowed to set up factories. Thai diplomatic missions were sent to Paris and The Hague. By keeping these ties, the Thai court cleverly played the Dutch against the English and French. This avoided too much influence from one power.

However, in 1664, the Dutch used force to get a treaty. This treaty gave them special rights and more access to trade. At the urging of his foreign minister, the Greek adventurer Constantine Phaulkon, Narai asked France for help. French engineers built forts for the Thais and a new palace for Narai in Lopburi. French missionaries also worked in education and medicine. They brought the first printing press to the country. King Louis XIV became interested when missionaries suggested Narai might become Christian.

The French presence, encouraged by Phaulkon, made Thai nobles and Buddhist monks resentful and suspicious. When news spread that Narai was dying, a general, Phetracha (reigned 1688–1693), staged a coup d'état. This was the Siamese revolution of 1688. He seized the throne, killed the chosen heir (who was Christian), and had Phaulkon and several missionaries executed. He then expelled the remaining foreigners. Some studies say Ayutthaya then became isolated from Western traders. But other recent studies argue that European merchants reduced their activities in the East due to wars in Europe. However, the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) continued to do business in Ayutthaya despite political difficulties.

-

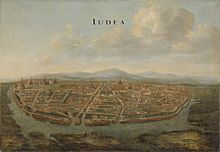

Siamese embassy to Louis XIV in 1686.

-

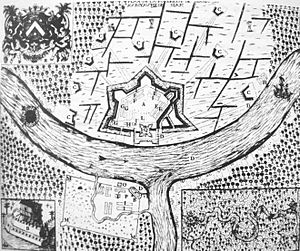

A portrait of Kosa Pan, a Thai ambassador to King Louis XIV of France.

Contact with East Asia

Between 1405 and 1433, the Chinese Ming dynasty sent out seven large naval expeditions. Emperor Yongle wanted to show China's power, control trade, and impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean. He also wanted to expand the tributary system. It is believed that the Chinese fleet, led by Admiral Zheng He, traveled up the Chao Phraya River to Ayutthaya three times.

Meanwhile, a Japanese community was set up in Ayutthaya. This community was active in trade. They exported deer hides and saphan wood to Japan. In return, they received Japanese silver and handicrafts like swords and high-quality paper. Japan was also interested in buying Chinese silks, deerskins, and ray or shark skins from Ayutthaya. These skins were used to make sword handles.

The Japanese quarter in Ayutthaya was home to about 1,500 Japanese people (some estimates say up to 7,000). The community was called Ban Yipun in Thai. It was led by a Japanese chief chosen by Thai authorities. It seems to have been a mix of traders, Christian converts who had fled Japan due to persecution, and former samurai who had lost battles.

A priest named António Francisco Cardim said he gave sacraments to about 400 Japanese Christians in Ayutthaya in 1627. There were also Japanese communities in Ligor and Patani.

-

Luang Pho Tho or Sam Pao Kong, a respected Buddha statue in Wat Phanan Choeng temple. Zheng He visited it in 1407.

Famous Foreigners in 17th Century Ayutthaya

- Constantine Phaulkon: A Greek adventurer and chief advisor to King Narai.

- François-Timoléon de Choisy: A French writer and diplomat.

- Father Guy Tachard: A French Jesuit writer and Siamese Ambassador to France.

- Louis Laneau: A French bishop in Siam.

- Claude de Forbin: A French Admiral.

- Yamada Nagamasa: A Japanese adventurer who became a ruler in Nakhon Si Thammarat.

- George White (merchant): An English merchant.

- Jeremias van Vliet: A Dutch merchant and official.

Studying Ayutthaya's History

Old Records of Ayutthaya

Many Ayutthaya texts were destroyed when the Burmese attacked in 1767. Van Vliet's writings from the early to mid-1600s are some of the earliest histories of Siam and Ayutthaya. He likely used religious temple records as his sources. The oldest surviving palace record is the Luang Prasoet chronicle, from 1681. Ayutthaya's history was not seen as very important until the peaceful and commercial times of the 1600s and 1700s. Early Ayutthaya did not write down its history. So, much of what we know comes from outside records. Besides Van Vliet, many Europeans in the 1600s and early 1700s wrote about Siam. Chinese palace records are also very important for understanding Ayutthaya's history.

The Ayutthaya Testimonies are another key source. These are based on what former residents of Ayutthaya said. They describe the city and kingdom before and during its fall in 1767.

Modern Views of Ayutthaya's History

The history of the Ayutthaya Kingdom has often been overlooked in Thailand and abroad. However, specific periods of Ayutthaya have been well-researched. Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit's "A History of Ayutthaya: Siam In the Early Modern World" (2017) was the first academic book in English to cover all 400 years of the kingdom. Historians in Southeast Asia often started writing national histories after colonial rule. Since Thailand was never fully colonized, it didn't have a European patron to help write its national history until Americans arrived in the 1960s.

In the early Rattanakosin period, King Rama I collected all surviving Ayutthaya laws. He published them as the Three Seals Law in 1805. Early Rattanakosin documents traced their "national" origins to Ayutthaya's founding in 1351. But in the early 1900s, Thai leaders were influenced by Western ideas of nationalism. They used this to create a nationalist history of Thailand. This view downplayed Ayutthaya's importance. It presented the Sukhothai Kingdom as the first "Thai" kingdom or a "golden age" of Thai culture. Rattanakosin was seen as a "rebirth," and Ayutthaya as a period of decline. This led to Ayutthaya being largely forgotten in Thai history for 50 years.

The nationalist histories of Ayutthaya, started by Prince Damrong, mainly focused on kings fighting wars and conquering neighboring states. These historical themes are still influential in Thailand today. But a new generation of historians began challenging these ideas in the 1980s. They focused more on the commercial and economic aspects important to Ayutthaya. New sources and translations from Chinese, Dutch, and other records have made Ayutthaya's history more accessible in recent decades.

Since the 1970s, new academics have challenged the old history. They have paid more attention to Ayutthaya. Charnvit Kasetsiri's "The Rise of Ayudhya" (1977) was a key work. Kasetsiri argued in 1999 that "Ayutthaya was the first major political, cultural, and commercial center of the Thai."

The "General Crisis" Idea

The idea that Ayutthaya declined after Europeans left in the late 1600s was popular. It was first used by the Rattanakosin court to make their new dynasty seem more legitimate. More recently, Anthony Reid's book on the "Age of Commerce" popularized this idea. However, newer studies, like Victor Lieberman's "Strange Parallels in Southeast Asia" and Baker and Phongpaichit's "A History of Ayutthaya," have mostly disagreed with Reid. Lieberman criticized Reid for using examples from Maritime Southeast Asia to explain Mainland Southeast Asia. He pointed to China's lifting of its trade ban and the increase in trade between China and Siam. Ayutthaya was historically important as a regional Asian trade center, not one where Europeans held much power for long.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Ayutthaya para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Ayutthaya para niños

- Ayutthaya Historical Park

- Ayutthaya Province

- Baan Hollanda

- Bang Rajan

- Family tree of Ayutthaya kings

- History of Thailand

- List of Ayutthaya kings

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |