Bayinnaung facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bayinnaungဘုရင့်နောင် |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Statue of Bayinnaung in front of the National Museum of Myanmar

|

|||||

|

Hanthawaddy (1552–1581)

Ava (1555–1581) Shan states (1557–1581) Manipur (1560–1581) Chinese Shan states (1562–1581) South Arakan (1580–1581) |

|||||

| Reign | 30 April 1550 – 10 October 1581 | ||||

| Coronation | 11 January 1551 at Toungoo 12 January 1554 at Pegu |

||||

| Predecessor | Tabinshwehti | ||||

| Successor | Nanda | ||||

| Chief Minister | Binnya Dala (1559–1573) | ||||

| Suzerain of Lan Na | |||||

| Reign | 2 April 1558 – 10 October 1581 | ||||

| Predecessor | New office | ||||

| Successor | Nanda | ||||

| King | Mekuti (1558–1563) Visuddhadevi (1565–1579) Nawrahta Minsaw (1579–1581) |

||||

| Suzerain of Siam | |||||

| Reign | 18 February 1564 – 10 October 1581 | ||||

| Predecessor | New office | ||||

| Successor | Nanda | ||||

| King | Mahinthrathirat (1564–1568) Maha Thammarachathirat (1569–1581) |

||||

| Suzerain of Lan Xang | |||||

| Reign | 2 January 1565 – c. January 1568 February 1570 – early 1572 6 December 1574 – 10 October 1581 |

||||

| Predecessor | New office | ||||

| Successor | Nanda | ||||

| King | Maing Pat Sawbwa (1565–1568, 1570–1572) Maha Ouparat (1574–1581) |

||||

| Born | 16 January 1516 Wednesday, 12th waxing of Tabodwe 877 ME Toungoo (Taungoo) |

||||

| Died | 10 October 1581 (aged 65) Tuesday, Full moon of Tazaungmon 943 ME Pegu (Bago) |

||||

| Burial | 15 October 1581 Kanbawzathadi Palace |

||||

| Consort | Atula Thiri Sanda Dewi Yaza Dewi |

||||

| Issue among others... |

Inwa Mibaya Nanda Nawrahta Minsaw Nyaungyan Min Khin Saw Yaza Datu Kalaya Thiri Thudhamma Yaza |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Toungoo | ||||

| Father | Mingyi Swe | ||||

| Mother | Shin Myo Myat | ||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||

Bayinnaung Kyawhtin Nawrahta (Burmese: ဘုရင့်နောင် ကျော်ထင်နော်ရထာ; 16 January 1516 – 10 October 1581) was a powerful king of the Toungoo Kingdom in Myanmar. He ruled from 1550 to 1581. During his 31-year reign, he created what was likely the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia. This huge empire included most of modern-day Myanmar, parts of China (the Chinese Shan states), Lan Na (in modern Thailand), Lan Xang (in modern Laos), Manipur (in modern India), and Siam (modern Thailand).

Bayinnaung is famous for building this large empire. However, his most important achievement was bringing the Shan states under control. These states had often raided Upper Burma since the late 1200s. After conquering the Shan states between 1557 and 1563, he set up a system that reduced the power of their traditional rulers, called saophas. He also made Shan customs more like those in the lowlands. This stopped the raids into Upper Burma. His policy for the Shan states was followed by Burmese kings until the British took over in 1885.

Bayinnaung could not use this same system everywhere in his vast empire. His empire was a loose collection of kingdoms that used to be independent. Their kings were loyal to him as the Cakkavatti (meaning "Universal Ruler"), not to the Toungoo Kingdom itself. Because of this, some parts of the empire, like Ava and Siam, rebelled just two years after he died. By 1599, all the kingdoms under his rule had revolted, and the Toungoo Empire completely fell apart.

Bayinnaung is seen as one of the three greatest kings of Burma, along with Anawrahta and Alaungpaya. Many important places in modern Myanmar are named after him. In Thailand, he is known as Phra Chao Chana Sip Thit, which means "Conqueror of the Ten Directions".

Contents

- Early Life of Bayinnaung

- Bayinnaung as a Leader

- Restoring the Toungoo Empire

- Expanding the Toungoo Empire

- Keeping the Empire Together

- Later Years of Bayinnaung

- How Bayinnaung Ruled

- Bayinnaung's Military Power

- Death and What Happened Next

- Bayinnaung's Family

- Bayinnaung's Legacy

- Commemorations

- See also

Early Life of Bayinnaung

His Family and Background

Bayinnaung was born Ye Htut on January 16, 1516. His parents were Mingyi Swe and Shin Myo Myat. His family's exact background is not fully clear from old records. Some historical writings say he came from a noble family in Taungoo. They connect him to earlier royal families of Burma.

However, some stories say his parents were ordinary people. His father was even said to be a toddy palm tree climber, which was a very humble job. These stories became popular later, showing that even someone from a simple background could become a great emperor in Burmese society. It's possible both stories are true: he could have had royal ancestors but still lived a simple life.

Growing Up in the Palace

No matter their background, Bayinnaung's parents were chosen to help care for the royal baby Tabinshwehti. Tabinshwehti was the prince and future king. Bayinnaung's mother became the prince's wet nurse. So, Bayinnaung's family moved into the Toungoo Palace.

Ye Htut grew up playing with Prince Tabinshwehti and the king's other children. This included Princess Thakin Gyi, who later became Bayinnaung's chief queen. He was educated in the palace alongside the prince. King Mingyi Nyo wanted his son to learn military skills. So, Tabinshwehti, Ye Htut, and other young men learned martial arts, horseback riding, elephant riding, and military strategy. Ye Htut became the prince's closest friend and helper.

Bayinnaung as a Leader

Becoming a Powerful Figure

When King Mingyi Nyo died on November 24, 1530, his 14-year-old son Tabinshwehti became king. The new king made Ye Htut's older sister, Khin Hpone Soe, one of his main queens. He also gave royal titles and jobs to his childhood friends and staff, including Ye Htut.

Ye Htut quickly became a powerful person in the kingdom. Toungoo was surrounded by strong enemies. To the north, the Confederation of Shan States had recently conquered the Ava Kingdom. To the south was the rich and powerful Hanthawaddy Kingdom. Toungoo leaders knew they had to act fast to avoid being taken over.

Ye Htut showed his bravery and strong character during these times. In 1532, he was with King Tabinshwehti when they boldly visited the Shwemawdaw Pagoda near Pegu, the capital of Hanthawaddy. This daring act went unpunished, showing how weak Hanthawaddy's ruler was. Ye Htut became the young king's constant companion and adviser.

Their close friendship was tested in 1534. Ye Htut had fallen in love with Princess Thakin Gyi, the king's half-sister. This was considered a serious crime. But instead of punishing Ye Htut, King Tabinshwehti decided to let them marry. He also gave Ye Htut the royal title of Kyawhtin Nawrahta. This decision earned Tabinshwehti the lasting loyalty of his brother-in-law.

Leading the Military

King Tabinshwehti's decision to trust Ye Htut paid off greatly. Between 1534 and 1549, Toungoo fought many wars and built the largest kingdom in Burma since the fall of Pagan in 1287. Ye Htut, now called Kyawhtin Nawrahta, won many important battles and helped manage the growing kingdom.

In late 1534, Toungoo attacked Hanthawaddy, a larger and richer kingdom to the south. Toungoo wanted to expand before the Shan Confederation turned its attention to them. Toungoo didn't have foreign guns yet, but they had many people who had moved there from other parts of Burma, giving them more soldiers.

Their first campaigns (1534–1537) failed against Pegu's strong defenses. But they learned from each attempt. In their 1538–1539 campaign, they finally broke through and captured Pegu. Kyawhtin Nawrahta became famous at the Battle of Naungyo. His smaller forces defeated a much larger Hanthawaddy army. After this victory, a thankful Tabinshwehti gave him the title Bayinnaung ("King's Elder Brother"). This is the name he is remembered by.

Toungoo went on to conquer all of Hanthawaddy by mid-1541. This gave them control of Lower Burma's people, access to foreign guns, and money to buy them. Tabinshwehti used these new resources to expand further. With Portuguese soldiers, guns, and fighting methods, Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung became even stronger military leaders. They also had help from experienced Hanthawaddy generals. Bayinnaung won key battles, allowing Toungoo to take over central Burma up to Pagan. After Bayinnaung crushed the Arakanese forces in April 1542, Tabinshwehti was so happy that he made Bayinnaung his chosen successor.

Later campaigns against Arakan (1545–1547) and Siam (1547–1549) were not as successful. Toungoo won all major battles but couldn't capture the heavily fortified capitals, Mrauk-U and Ayutthaya, which had Portuguese guns. They didn't have enough soldiers for long sieges. Still, by 1549, Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung had built the largest kingdom in Burma since the fall of the Pagan Empire in 1287. It stretched from Pagan in the north to Tavoy in the south.

Managing the Kingdom

Bayinnaung was also trusted with running the kingdom. In 1539, Tabinshwehti made him chief minister. At that time, the chief minister's job was to manage and coordinate different parts of the kingdom. Local rulers still had control over daily tasks and people. Trusted local leaders helped Bayinnaung with central administration.

In 1549, King Tabinshwehti started to lose interest in ruling. He gave all his duties to Bayinnaung and spent much time hunting. Ministers asked Bayinnaung to take the throne, but he refused. He wanted to help the king return to his duties. However, he was not successful. Even when a serious rebellion started in January 1550, the king asked Bayinnaung to deal with it and went hunting again.

Restoring the Toungoo Empire

A Kingdom Without a King

On April 30, 1550, King Tabinshwehti was killed by his own bodyguards. One of his advisers, Smim Sawhtut, declared himself king. But many other governors and leaders also claimed to be king, including Bayinnaung's own half-brother. Even though Bayinnaung had been chosen as Tabinshwehti's successor since 1542, no one recognized him.

When Bayinnaung heard the news, he was far away, fighting rebels. The Toungoo Empire, which he had helped build for 16 years, was now in ruins. He was, as one historian said, "a king without a kingdom."

Bayinnaung had to rebuild everything. He was in Dala (modern Yangon) with only a few loyal soldiers. His two younger brothers were with him and remained loyal. He also had a trusted commander named Binnya Dala. Bayinnaung sent for his favorite Portuguese soldier, Diogo Soares de Mello, who returned with his 39 men.

Two months after the assassination, Bayinnaung began his plan to restore the kingdom. He faced several rivals who had taken control of different regions.

Taking Back Central Burma (1550–1551)

Toungoo, the Homeland

Bayinnaung and his advisers decided to start by taking back Toungoo, the original home of their dynasty. This was a risky plan because they had to march through enemy territory. But they believed Bayinnaung would find the most support in his hometown.

In late June, Bayinnaung and his small army left Dala for Toungoo. They marched north, avoiding Pegu. Smim Sawhtut, who was now "king" of Pegu, tried to stop them but didn't engage. Bayinnaung set up camp near Toungoo. Many ministers and soldiers from Tabinshwehti's old court, who had fled Pegu, joined him. These new arrivals were from different ethnic groups, showing that loyalty to a leader was often more important than ethnic background.

By late August, he had a strong fighting force. On September 2, 1550, his army attacked Toungoo. Bayinnaung's half-brother, Minkhaung II, resisted for four months. But on January 11, 1551, he finally surrendered. Bayinnaung forgave his brother. On the same day, Bayinnaung was crowned king in a temporary palace. He rewarded his loyal men with new titles and jobs. His oldest son, Nanda, was named the next in line to the throne.

Conquering Prome and Pagan

Bayinnaung's next target was Prome. In March 1551, his army attacked the city. Prome's strong defenses, with muskets and cannons, kept them away for over three months. Bayinnaung retreated to gather more men from central Burma. He resumed the attack on August 21, 1551, and took the city on August 30, 1551. He appointed his second younger brother as the new ruler of Prome.

Bayinnaung then completed the conquest of northern central Burma up to Pagan by mid-September 1551. He appointed his uncle as governor. He then marched towards Ava, hoping to take advantage of a civil war there. But he had to quickly withdraw when Pegu forces marched towards Toungoo.

Taking Back Lower Burma (1552)

Pegu's forces left his territory, but Bayinnaung decided Pegu had to be defeated first. Meanwhile, Mobye Narapati, who had been driven out of Ava, joined Bayinnaung. After five months of planning, Bayinnaung's army left Toungoo for Pegu on February 28, 1552. They arrived on March 12, 1552.

Smim Htaw, who had taken over Pegu, challenged Bayinnaung to a one-on-one fight on war elephants. Bayinnaung accepted and won, driving Htaw and his elephant away. Htaw's men fled.

Htaw and his small army retreated to the Irrawaddy delta. Toungoo armies followed, taking eastern delta towns by the end of March. Htaw's army briefly recaptured Dala but was finally defeated near Bassein in mid-May. His entire army was captured, but Htaw escaped. He remained a fugitive until he was caught and executed in March 1553. By mid-1552, Bayinnaung controlled all three Mon-speaking regions. He appointed his oldest younger brother as the new ruler of Martaban on June 6, 1552.

Coronation as King

Two years after Tabinshwehti's death, Bayinnaung had restored the empire. But he felt his work was not finished because Siam had not sent him tribute. He thought about invading Siam, but his advisers told him to attack Ava first. He sent an army led by his son Nanda in June 1553. But Ava's new king was ready and had many allies. Nanda had to call off the invasion.

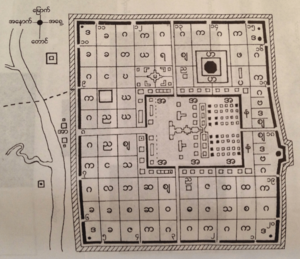

Bayinnaung decided to strengthen his control instead. He ordered a new palace, called Kanbawzathadi, to be built in his capital, Pegu. It was opened on November 17, 1553. On January 12, 1554, he was officially crowned king with the name Thiri Thudhamma Yaza. His chief queen, Thakin Gyi, was crowned Agga Mahethi.

Expanding the Toungoo Empire

By taking back Lower Burma, Bayinnaung gained control of foreign guns and money. Over the next two decades, he used these resources to expand his empire even further. By adding people and resources from newly conquered lands, he built the largest empire in Southeast Asian history.

Conquering Upper Burma (1554–1555)

By late 1554, Bayinnaung had gathered a huge invasion force of 18,000 men, 900 horses, and 80 elephants. This was his largest army yet. In November 1554, Toungoo forces launched a two-part invasion. Ava's defenses, supported by nine Shan armies, could not stop them. The capital, Ava, fell on January 22, 1555. King Sithu Kyawhtin was sent to Pegu. Bayinnaung appointed his younger brother Thado Minsaw as the new ruler of Ava. Toungoo forces then drove out the remaining Shan armies from the region by late March.

Bayinnaung now controlled the main river valleys of Burma. However, his control over Upper Burma was still weak because he had not secured the loyalty of the surrounding Shan states. These states had been raiding the area for centuries. He needed to bring them under control to keep Upper Burma safe.

Bringing in the Shan States (1557)

By 1556, the king decided to conquer all the Shan states near the Irrawaddy valley at once. They also knew they might have to fight Lan Na (Chiang Mai), which was an ally of a powerful Shan state. The Toungoo army spent a year preparing their largest army yet for this invasion.

The invasion of the Shan country began in January 1557. The huge army worked. States surrendered one after another with little fighting. By March 1557, Bayinnaung controlled most of the Shan states west of the Salween River. But trouble started after the army left. The powerful state of Mone, which had not been invaded, revolted with help from Lan Na. Mone forces took over Thibaw and killed the new ruler Bayinnaung had appointed. In November 1557, Bayinnaung himself led five armies to easily conquer Mone and Thibaw.

By the end of 1557, only the Shan states that were under Chinese rule remained outside Bayinnaung's control.

Taking Lan Na (1558)

Bayinnaung then looked towards the once-powerful Kingdom of Lan Na. When Bayinnaung and his armies arrived at Chiang Mai on March 31, 1558, King Mekuti surrendered without a fight on April 2, 1558. The Burmese king allowed Mekuti to remain ruler of Lan Na. He also brought many skilled workers back to Pegu. He left a small group of 1000 soldiers in Chiang Mai.

Soon after the main armies left, trouble started again. King Setthathirath of Lan Xang took over some eastern provinces of Lan Na. In November 1558, a large army led by Bayinnaung's brother reinforced Chiang Mai's defenses. From there, the combined armies successfully drove out the Lan Xang forces.

Manipur and Other Shan States (1559–1563)

Lan Xang's defeat showed that Toungoo Burma was the strongest power in the Shan region. The remaining Shan states that were under Chinese rule also submitted.

Bayinnaung immediately used the people from newly conquered areas to gain more territory. In December 1559, he ordered an invasion of Manipur. The three armies, mostly made up of soldiers from the Shan states, faced little resistance. The Manipuri king surrendered around February 1560.

The king spent the next two years preparing for war against Siam. He wanted to bring the Shan states east of the Salween River under his control first. This would give him more soldiers and secure his borders. In March/April 1563, his armies launched an invasion. They faced little resistance and gained the loyalty of the local rulers. Bayinnaung now had control over these Chinese Shan states.

Conquering Siam (1563–1564)

With much of mainland Southeast Asia under his control, Bayinnaung felt ready to take on Siam. He needed a huge advantage in soldiers because Siam was a rich coastal power with its own Portuguese guns and soldiers. On July 16, 1563, he sent a message to Siam, demanding one of the four white elephants owned by the Siamese king as tribute. As expected, King Maha Chakkraphat refused. On November 1, 1563, five armies (60,000 men, 2400 horses, and 360 elephants) left Pegu to start the campaign.

The armies took the important central city of Kamphaeng Phet on December 4, 1563. Three armies then spread out to take other key cities in central Siam. They faced little opposition, and the rulers of these cities submitted.

The armies then marched to Ayutthaya. The Siamese fort, helped by Portuguese warships and cannons, kept them away for weeks. The invaders finally captured the Portuguese ships and cannons on February 7, 1564. After that, the fort quickly fell. The Siamese king surrendered on February 18, 1564. Bayinnaung took all four white elephants and other treasures. He sent the defeated king to Pegu. He appointed a son of the fallen king as the new ruler of Siam and left 3000 soldiers there.

Lan Na and Lan Xang (1564–1565)

Even after conquering Siam, Bayinnaung still needed to deal with the middle Tai country. King Mekuti of Lan Na had allied with his old rival, King Setthathirath of Lan Xang. On October 23, 1564, Bayinnaung himself led five massive armies (64,000 men, 3600 horses, 330 elephants) to invade Lan Na. Soldiers came from all over his empire, including Siam.

The huge show of force worked. When four armies arrived near Chiang Mai, the city's defenders simply fled. Mekuti surrendered and asked for forgiveness. Bayinnaung spared the king's life and sent him to Pegu. The Burmese king stayed in Lan Na for four months, managing the country. He appointed Queen Visuddhadevi as the new ruler of Lan Na before leaving Chiang Mai on April 10, 1565, to deal with a serious rebellion in Pegu.

Lan Xang, however, was much harder to conquer. Three armies invaded Lan Xang and easily captured Vientiane on January 2, 1565. But King Setthathirath escaped. For several months, the Burmese troops chased him and his small group of men around the countryside. Many soldiers died from hunger and disease. The Burmese finally gave up and left Vientiane on August 1, 1565. They had placed a son-in-law of Setthathirath as the new ruler. They also brought back many members of the Lan Xang royal family.

Lan Na remained peaceful for the rest of Bayinnaung's reign. But in Vientiane, the new ruler's power didn't extend much beyond the capital. Setthathirath remained active in the countryside and returned to Vientiane in late 1567.

Keeping the Empire Together

A Brief Calm (1565–1567)

After a rebellion in Pegu in 1565, Bayinnaung had no new rebellions for the next two years. The rebellion had burned down large parts of the capital, including the palace. So, he had the capital and palace rebuilt. The new capital had 20 gates, each named after the ruler who built it. Each gate was beautifully decorated.

The newly rebuilt Kanbawzathadi Palace officially opened on March 16, 1568. All the rulers under Bayinnaung were present. He even gave higher titles to four former kings living in Pegu, including the deposed kings of Ava, Lan Na, and Siam.

Trouble in Lan Xang and Siam (1568–1569)

Even as Bayinnaung celebrated in his new palace, trouble was starting in Lan Xang. About a month earlier, he learned that Setthathirath's forces had not only retaken Vientiane but were also raiding parts of Siam and Lan Na. Bayinnaung quickly sent troops to the border, but this small army was defeated.

More bad news came. On May 12, 1568, he learned that southern Siam (Ayutthaya) had also rebelled and allied with Lan Xang. The rebellion was led by Maha Chakkraphat, the former king of Siam. Bayinnaung had just honored him and allowed him to return to Ayutthaya as a monk. But as soon as the monk arrived, he threw off his robes and declared independence. However, the ruler of central Siam remained loyal to Bayinnaung. On May 29, 1568, Bayinnaung sent an army to help him.

The war began in June. Ayutthaya and Lan Xang forces tried to capture central Siam before Bayinnaung's main invasion. They laid siege to Phitsanulok, but its strong defenses held. In late October, the attackers retreated. Bayinnaung's five armies arrived at Phitsanulok on November 27, 1568. With more soldiers, their combined armies marched to Ayutthaya and began a siege in December 1568.

The Burmese armies faced heavy losses but could not break through for months. When Setthathirath and his army came to help Ayutthaya, Bayinnaung left his general in charge of the siege and went to meet the enemy. On May 8, 1569, he decisively defeated Setthathirath. Meanwhile, Maha Chakkraphat had died. His son offered to surrender under certain conditions, but Bayinnaung demanded an unconditional surrender. He sent one of his Siamese nobles into the city, pretending to be a deserter. This spy helped open one of the city's gates. Ayutthaya fell on August 2, 1569. Bayinnaung appointed Maha Thammarachathirat as the new king of Siam on September 29, 1569.

Controlling Distant Regions

While Bayinnaung had defeated Siam, his most powerful rival, his biggest challenge was keeping control of remote, mountainous states. Guerrilla warfare by small rebel groups, combined with difficult terrain and hunger, caused more problems for his armies than Siam ever did.

Lan Xang's Troubles (1569–1573)

The remote, hilly region of Lan Xang was especially troublesome. Bayinnaung personally led an invasion of Lan Xang in October 1569. Setthathirath fought at Vientiane for a few months before retreating into the jungle in February 1570 to use guerrilla tactics. Bayinnaung's troops spent two months searching for him, but many died from hunger and long marches. Bayinnaung finally gave up and returned home in April 1570. Very few of his original army survived the journey back to Pegu.

Meanwhile, Setthathirath's forces attacked the Burmese soldiers in Vientiane. Luckily for the Burmese, the Lan Xang king was killed sometime before mid-1572. A general named Sen Soulintha took the throne. Soulintha refused Bayinnaung's demand to surrender. Bayinnaung was surprised and sent a small army to invade. But he had underestimated the enemy. The small Burmese army suffered from guerrilla attacks and had to retreat in early 1573. Bayinnaung was very angry with his general, Binnya Dala, and sent him away. The general, who had won many battles for Bayinnaung, died from illness six months later.

Northern Shan States (1571–1577)

Lan Xang was not the only remote region that caused problems. The northern Shan states of Mohnyin and Mogaung rebelled in July 1571. Bayinnaung sent two large armies. The armies easily recaptured the states. But, like in Lan Xang, the troops spent five difficult months chasing the rebel leaders in the snowy mountains.

The king was particularly annoyed that the leader of the Mogaung rebellion had grown up in the Pegu palace and had been appointed by him. He personally marched north in late 1575. One group of soldiers found and killed the ruler of Mohnyin. But the ruler of Mogaung escaped and remained free for another year and a half. When he was finally captured on September 30, 1577, the king ordered him to be displayed in chains at each of Pegu's twenty gates for a week. Then, he and his followers were sold as slaves in India.

Lan Xang Again (1574–1575)

Bayinnaung immediately ordered a new army to invade Lan Xang. But the kingdom had been constantly at war, and his yearly demands for more soldiers were pushing his vassals to their limit. Even his senior advisers complained, and the king reluctantly agreed to wait a year. This break did little to help his tired vassals. When the call for soldiers came in 1574, the northernmost states of Mohnyin and Mogaung refused and rebelled.

The king was not bothered. He ordered his brother, the ruler of Ava, to deal with the northern states. Bayinnaung himself led the Lan Xang campaign. On October 1, 1574, his brother's army marched north. Six days later, Bayinnaung's four armies began the Lan Xang campaign. The armies arrived at Vientiane after 60 days of marching. On December 6, 1574, the king and his huge armies entered Vientiane without fighting, as Soulintha had already left. Luckily for the Burmese king, Soulintha was seen as an unfair ruler by his own officers. They arrested him and gave him to Bayinnaung. Burmese armies then spread out and received tribute from the Lao countryside. The Burmese king appointed a younger brother of Setthathirath as the new king of Lan Xang. Bayinnaung returned to Pegu on April 16, 1575. Since the new king was a true Lan Xang royal, the people accepted him. Lan Xang was finally under control.

Later Years of Bayinnaung

Relations with Ceylon

By 1576, almost no one dared to challenge Bayinnaung's rule. The rest of his reign was relatively peaceful. Other kingdoms in the region, especially in Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), wanted his support. Bayinnaung saw himself as the protector of Theravada Buddhism. He had long tried to promote and protect the religion in Ceylon.

In the 1570s, two kingdoms in Ceylon, Kotte and Kandy, tried to get Bayinnaung's help. King Dharmapala of Kotte was the most active. He sent what he claimed was his daughter to Bayinnaung. The princess was welcomed with great celebration in Bassein on September 24, 1573. Some historians say the Kotte king was forced to send a princess to fulfill a prophecy. Since he had no daughters, he sent a chamberlain's daughter, whom he treated as his own.

Dharmapala, who had become a Catholic, continued to seek favor. He sent what he claimed was the real Tooth Relic of the Buddha, supposedly for safekeeping under the great Buddhist king. His main goal was to get military help against a rebellion. The Tooth was received on July 14, 1576. Bayinnaung sent 2500 of his best soldiers to Colombo. These troops easily defeated the rebellion. The Burmese generals then met with the rulers of the four kingdoms of Ceylon and told them to protect Buddhism.

Peace in Lan Na and Lan Xang (1579)

No problems arose when Queen Visuddhadevi of Lan Na, who had kept the middle Tai country peaceful for over 13 years, died on January 2, 1579. Bayinnaung's chosen son, Nawrahta Minsaw, took over the Lan Na throne without any issues. When problems started in Lan Xang, he took no chances. On October 17, 1579, he sent a large army, which faced no opposition. According to Laotian history, the king of Lan Xang died in 1580, and Bayinnaung installed Sen Soulintha, the former usurper he had kept in Pegu since 1574, as the new ruler.

Arakan Campaign (1580–1581)

By 1580, Bayinnaung had brought all the countries that had occupied his attention for three decades under his control. He faced no internal or external threats. Instead of resting, he turned his attention to Arakan, a kingdom he and Tabinshwehti had tried to conquer unsuccessfully in 1545–1547. He decided it was time to make Arakan a vassal state again, as it had been under the Pagan kings.

The king sent an 8000-strong naval invasion force on October 15, 1580. The fleet, with 200 ships, occupied Sandoway in November 1580. The king had probably planned to lead the attack on the Arakanese capital himself, but he couldn't because his health was failing. The invasion force remained inactive at Sandoway for a year. The king sent more land and naval forces on August 28, 1581, to prepare for the upcoming dry season campaign. But the king died six weeks later, and the invasion forces soon withdrew.

How Bayinnaung Ruled

A Vast Empire

Bayinnaung successfully built the largest empire in Burmese history. It stretched from Manipur in the northwest to areas near Vietnam and Cambodia in the east. It also went from the Chinese Shan states in the north to the central Malay peninsula in the south. It was likely the largest empire in Southeast Asian history. The Portuguese called Pegu "the most powerful monarchy in Asia except that of China."

However, Bayinnaung, who started as "a king without a kingdom," ended his reign as an "emperor without an empire." He conquered territories not to fully take them over, but to gain the loyalty of their rulers. He allowed conquered kings and lords to keep their positions as long as they remained loyal to him. This huge kingdom was held together by personal relationships and loyalty, rather than by strong formal government systems. He presented himself as a cakkavatti, or "World Ruler."

This was a common way of ruling in Southeast Asia at the time. The main king ruled the core area, while semi-independent rulers controlled the daily administration and people in other parts. So, the "King of Kings" directly governed only Pegu and the Mon country. The rest of the empire was left to vassal kings in places like Ava, Prome, Lan Na, Lan Xang, Martaban, Siam, and Toungoo. He considered Lan Na the most important vassal state and spent a lot of time there.

Changes to Administration

Bayinnaung made only small changes to how the empire was run. He mostly used the existing decentralized system, which had barely worked for small states like his home Toungoo. Now, applied to a huge empire, the system was even more spread out and weak. However, it was the only system the Toungoo kings knew.

He did introduce one important change, perhaps by accident, which became his most lasting legacy. This was his policy for ruling the Shan states. He allowed the Shan rulers, called saophas, to keep their royal symbols and ceremonies. Their position remained hereditary. But the king could now remove a saopha for bad behavior, though the new saopha still had to be from the same family. A key new rule was that the sons of these vassal rulers had to live in his palace as pages. This served two purposes: they were hostages to ensure their fathers' good behavior, and they learned about Burmese court life. This Shan policy was followed by all Burmese kings until the British took over in 1885.

However, his changes were not fully planned and were still being tested. Personal loyalty was still much more important than weak government systems. His vassals were loyal to him, not to the Toungoo Kingdom itself. The changes he started would be expanded by later kings. But they were not strong enough by the time he died to stop his huge empire from quickly falling apart in the next two decades.

Laws and Trade Rules

Bayinnaung brought some legal order by asking wise monks and officials from all over his lands to create an official collection of law books. These scholars put together new law books based on older ones. Decisions made in his court were also collected. He promoted these new laws throughout the empire, as long as they fit with local customs. The use of Burmese law and the Burmese calendar in Siam began during his reign. He also made sure that weights and measurements, like the cubit and tical, were the same throughout his empire.

His kingdom was mainly based on farming, with a few rich trading ports. The main ports were Syriam, Dala, and Martaban. The kingdom exported goods like rice and jewels. In Pegu, eight brokers chosen by the king handled overseas trade. European merchants respected their honesty. The capital city was very wealthy. Travelers from Europe often described Pegu's moat, walls, palace, grand parades, and shrines filled with gold and jewels. The king appointed officials to oversee merchant ships and sent out ships for trade. However, the countryside probably wasn't as rich. Yearly demands for soldiers meant fewer people were available to farm, sometimes causing severe rice shortages.

Religious Activities

Another lasting impact of Bayinnaung was his promotion of a more traditional form of Theravada Buddhism in Upper Burma and the Shan states. He continued the religious changes started by King Dhammazedi. Seeing himself as a "model Buddhist king," he shared copies of holy texts, fed monks, and built pagodas in every new land he conquered. Some of these pagodas can still be seen today. He also oversaw large ceremonies where people became monks in Pegu, aiming to make the religion purer. He banned all human and animal sacrifices throughout his kingdom. For example, he stopped the Shan practice of killing slaves and animals at a ruler's funeral. However, his efforts to remove traditional spirit worship from Buddhism were not fully successful.

He gave jewels to decorate the tops of many pagodas, including the Shwedagon, the Shwemawdaw, and the Kyaiktiyo. He added a new spire to the Shwedagon in 1564 after his beloved queen died. His main temple was the Mahazedi Pagoda in Pegu, which he built in 1561. He tried but failed to get the Tooth Relic of Kandy back from the Portuguese in 1560. He later got involved in Ceylon's affairs in the 1570s, supposedly to protect Buddhism there.

Bayinnaung's Military Power

Bayinnaung built the largest empire in Southeast Asia through amazing military conquests. His success came from a strong military tradition, Portuguese guns, foreign soldiers, and larger armies.

First, he grew up in Toungoo, a place often in rebellion. He received military training from childhood. He and Tabinshwehti launched their first campaign when they were only 18.

Second, his military career started just as Portuguese cannons and muskets became widely available. Portuguese weapons were better than Asian-made ones. Bayinnaung quickly used this to his advantage, adding Portuguese guns and soldiers to his forces. Burmese soldiers also started using guns. Some historians believe that if Toungoo had attacked Pegu later, Portuguese guns might have given Pegu the victory. But Toungoo used these advantages to build an empire.

Finally, Bayinnaung could gather more soldiers than any other ruler in the region. He required every new conquered state to provide soldiers for his next campaign. Using larger armies and better guns, he easily brought Manipur and the Shan states under his control. His larger forces and their greater fighting experience made the difference against Siam, which also had a powerful and well-equipped military.

However, Siam was not his biggest enemy. The remote mountainous states like Lan Xang, Mohnyin, and Mogaung caused him constant trouble with their guerrilla warfare. Many of his men died from hunger and disease while searching for these hidden rebels year after year. He was lucky that the skilled guerrilla leader Setthathirath died. In the end, his military strength alone could not bring lasting peace. He needed good local rulers who were respected by the people to govern the lands for him. History shows that he used political solutions to keep the peace.

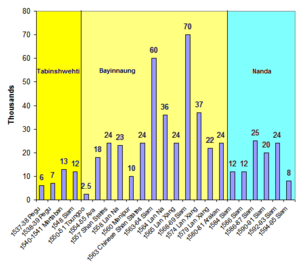

His success was unique. He gathered 60,000 to 70,000 men for his major campaigns. Later Toungoo kings could only gather a third of that. It wasn't until much later that the Burmese army could gather so many men again. Historians note that he was constantly leading campaigns himself. The failure of other kings who tried the same conquests shows how great his abilities were.

Death and What Happened Next

King Bayinnaung died on October 10, 1581, after a long illness.

His oldest son and chosen successor, Nanda, took over the throne without any problems. But the empire, which Bayinnaung had built through military conquests and kept together with both military power and personal relationships, soon began to fall apart.

The first sign of trouble appeared in the far north in September 1582 when some Chinese Shan states rebelled. This rebellion was put down in March 1583. More serious problems followed. Ava (Upper Burma) revolted in October 1583, and that rebellion was put down in April 1584. Siam rebelled on May 3, 1584. Nanda would spend the rest of his reign fighting Siam and other former vassal states. By 1599, he had lost the entire empire.

Bayinnaung's Family

The king had three main queens and over 50 other queens. In total, he had 97 children. Here are some of his notable queens and their children:

| Queen | Rank | Children |

|---|---|---|

| Atula Thiri Maha Yaza Dewi | Chief Queen | Inwa Mibaya, Queen of Ava Nanda, King of Burma |

| Sanda Dewi | Senior Queen (1553–68) Chief queen (1568–81) |

Min Khin Saw, Queen of Toungoo |

| Yaza Dewi | Senior Queen | Nawrahta Minsaw, King of Lan Na Yaza Datu Kalaya, Crown Princess of Burma Thiri Thudhamma Yaza, Ruler of Martaban |

| Khin Pyezon | Junior queen | Shin Ubote, Governor of Nyaungyan Nyaungyan, King of Burma |

In Thai history, a famous queen of Bayinnaung was Suphankanlaya, daughter of King Maha Thammarachathirat of Siam.

Bayinnaung's Legacy

Bayinnaung is considered one of the three greatest Burmese kings, along with Anawrahta and Alaungpaya. These kings founded the First and Third Burmese Empires. Bayinnaung is mostly remembered for his military conquests in Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos. His reign has been called a time of "the greatest explosion of human energy ever seen in Burma." In Myanmar, military leaders often see him as their favorite king. They feel they are fighting the same enemies in the same places. His statues are there to show how a nation was built by force.

In Thailand, he is known as the "Conqueror of the Ten Directions." This name comes from a famous novel. He is generally treated with respect in Thailand. In Laos, King Setthathirath is celebrated for his strong resistance against the empire.

Even though he is best known for building an empire, his most important legacy was bringing the Shan states under control. This stopped the Shan raids into Upper Burma, which had been a problem since the late 1200s. His Shan policy, which was improved by later Toungoo kings, reduced the power of the traditional Shan rulers. It also made hill customs more like lowland ones. This policy was followed by Burmese kings until the British took over in 1885.

The use of Burmese customary law and the Burmese calendar in Siam began during his reign. Siam used the Burmese calendar until 1889.

Commemorations

Bayinnaung is remembered in Myanmar in several ways:

- Bayinnaung Bridge, a suspension bridge in Yangon.

- Bayinnaung Market, a major market in Yangon.

- Bayinnaung Road, a road in Yangon.

- Bayinnaung Statue, one of three statues of kings that stand over the main parade square in Naypyidaw. The other two are Anawrahta and Alaungpaya.

- Cape Bayinnaung, the southernmost point of mainland Myanmar.

- Team Bayinnaung, one of the five student teams in Burmese primary and secondary schools.

- UMS Bayinnaung, a Myanmar Navy ship.

See also

In Spanish: Bayinnaung para niños

In Spanish: Bayinnaung para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |