Fra Mauro map facts for kids

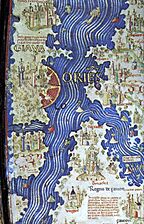

The Fra Mauro map is a map of the world made around 1450 by the Italian (Venetian) cartographer Fra Mauro. It took several years to complete and was very expensive to produce. The map contains hundreds of detailed illustrations and more than 3000 descriptive texts. It was the most detailed and accurate representation of the world that had been produced up until that time. As such, the Fra Mauro map is considered one of the most important works in the history of cartography.

The maker of the map, Fra Mauro, was a Camaldolese monk from the island of Murano near Venice. He was employed as an accountant and professional cartographer. The map was made for the rulers of Venice and Portugal, two of the main seafaring nations of the time.

This map was drawn on special animal skin called parchment. It's set in a wooden frame and is huge – over two meters (about 6.5 feet) tall and wide! It shows Asia, the Indian Ocean, Africa, Europe, and the Atlantic Ocean. What's really cool is that it's drawn with South at the top, which was unusual for European maps back then.

The map is usually on display in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice in Italy.

Contents

Exploring the Fra Mauro Map

This map is truly massive! The entire frame measures about 2.4 by 2.4 metres (8 by 8 ft). This makes Fra Mauro's mappa mundi the largest map from early modern Europe that still exists today. The map is drawn on high-quality vellum (a very fine type of parchment) and is set in a beautiful gilded (gold-covered) wooden frame. The large drawings are super detailed and use many expensive colors like blue, red, turquoise, brown, green, and black.

The main circular map of the world is surrounded by four smaller circles, each showing something different:

- The top-left circle is a cosmological diagram – a map of the Solar System as people understood it back then, following the Ptolemaic system (where Earth was thought to be the center).

- The top-right circle shows a diagram of the four elements – earth, water, fire, and air.

- The bottom-left circle is an illustration of the Garden of Eden. What's important here is that Fra Mauro chose to place the Garden of Eden outside the main world map, instead of its traditional spot in the far east.

- The bottom-right circle shows Earth as a globe. It even shows the North Pole and the South Pole, as well as the Equator and the two tropics (lines of latitude).

There are about 3,000 descriptions and detailed texts written all over the map. These texts explain the different geographical features and give extra information about them. The way the map shows towns, cities, and mountains (this is called chorography) is also a key feature. Castles and cities are shown with little pictures of castles with towers or walled towns, and their size shows how important they were.

Making this map was a huge project that took several years. Fra Mauro didn't do it alone; he led a team of mapmakers, artists, and copyists. They used some of the most expensive techniques available at the time. The cost of the map would have been about the same as an average copyist's yearly salary!

Different Versions and Copies of the Map

Fra Mauro's workshop actually made two original versions of the map. Plus, at least one high-quality copy was made later using the same materials.

- One version was ordered by the Signoria of Venice – the main government body of the Republic of Venice. This map still exists today! It was "found again" in the monastery of St. Michael in Murano, where Fra Mauro had his studio. You can usually see it on public display in the Museo Correr in Venice.

- Another version of the map was made for King Afonso V of Portugal. Fra Mauro and his assistant, Andrea Bianco (who was a sailor and mapmaker), finished this map on April 24, 1459. It was then sent to Lisbon in Portugal. Records show this map was kept in the royal palace of São Jorge Castle until at least 1494, but sometime after that, it disappeared. There might be a copy or an original of this map from the 15th century in the Lisbon naval museum.

In 1804, a British mapmaker named William Frazer made a full copy of the map on vellum. Even though his copy is very exact, there are tiny differences between the original Venetian map and the British copy. The Frazer copy is currently on display in the British Library in London. Some of the images you see in this article are from the Venetian original, and some are from the Frazer copy.

Many historians who study maps, starting with Giacinto Placido Zurla in 1806, have studied Fra Mauro's map. A special, detailed edition of the map was put together by Piero Falchetta in 2006.

How the Map is Oriented and Centered

The Fra Mauro world map is quite unusual because it's oriented with South at the top. This was also common in Fra Mauro's portolan charts (special navigation maps). One idea for why South is at the top is that compasses in the 15th century often pointed south. Also, Arab maps of that time often had South at the top.

In contrast, most European mappae mundi from that era placed East at the top, because East was believed to be the direction of the biblical Garden of Eden. Other well-known world maps of the time, like the Ptolemy map, placed North at the top. Fra Mauro knew about the religious importance of East and also about the Ptolemy map. He felt he needed to explain why he changed the orientation in his new world map:

I don't think it's wrong to not follow Ptolemy's Cosmographia, because to follow his lines of longitude or latitude or degrees, I would have to leave out many places he didn't mention. But especially in latitude, from south to north, he has a lot of terra incognita (unknown land), because it was unknown in his time.

In another break from tradition, Jerusalem is not shown as the center of the world. Fra Mauro explained this change by saying:

Jerusalem is indeed the center of the inhabited world from side to side (latitudinally), though from top to bottom (longitudinally) it is somewhat to the west. But since the western part is more densely populated because of Europe, Jerusalem is also the center longitudinally if we consider not empty space but how many people live there.

Exploring the Continents on the Map

Europe on the Map

The European part of the map, which was closest to Fra Mauro's home in Venice, is the most accurate. The map shows the Mediterranean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean coast, the Black Sea, and the Baltic Sea, and it stretches as far as Iceland. The coasts of the Mediterranean are very accurate, and every major island and land mass is shown. Many cities, rivers, and mountain ranges of Europe are also included.

Great Britain on the Map

Two descriptions on the map talk about England and Scotland. They mention giants, the Saxons, and Saints Gregory and Augustine:

Note that in ancient times Anglia [England] was inhabited by giants, but some Trojans who had survived the slaughter of Troy came to this island, fought its inhabitants and defeated them; after their prince, Brutus, it was named Britannia. But later the Saxons and the Germans conquered it, and after one of their queens, Angela, called it Anglia. And these peoples were converted to the Faith by means of St. Gregory the pope, who sent them a bishop called Augustine.

This story likely comes from the Historia Regum Britanniae, a famous book from the 1100s that tells tales of the early kings of England. It's famous for being one of the first texts to include King Arthur. It tells a similar story where Brutus of Troy, a descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas, escapes Rome to conquer Great Britain from its native inhabitants, the Giants.

As it is shown, Scotia [Scotland] appears connected to Anglia, but in its southern part it is divided from it by water and mountains. The people are easygoing and are fierce and cruel against their enemies; and they prefer death to being enslaved. The island is very fertile in pastures, rivers, springs and animals and all other things; and it is like Anglia.

Scandinavia is the least accurate part of the European section. A description about Norway and Sweden talks about tall, strong, and fierce people, polar bears, and St. Bridget of Sweden:

Norvegia [Norway] is a very vast province surrounded by the sea and joined to Svetia [Sweden]. Here they produce no wine or oil, and the people are strong, robust and of great stature. Similarly, in Svetia the men are very fierce; and according to some, Julius Caesar was not eager to face them in battle. Similarly, these peoples were a great problem for Europe; and at the time of Alexander, the Greeks did not have the courage to conquer them. But now they are much smaller and do not have the reputation they formerly had. Here is said to be the body of St. Bridgit, who some say was from Svetia. And it is also said there are many new kinds of animals, especially huge white bears and other wild animals.

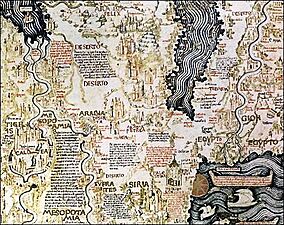

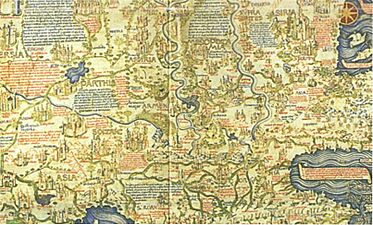

Asia on the Map

The Asian part of the map shows the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, the Indian subcontinent (including the island of Sri Lanka), and the islands of Java and Sumatra. It also includes Burma, China, and the Korean peninsula. The Caspian Sea, which borders Europe, has an accurate shape, but the outline of Southern Asia is a bit stretched. India is shown in two halves. Major rivers like the Tigris, the Indus, the Ganges, the Yellow, and the Yangtze are all drawn. Cities include Baghdad, Beijing, Bokhara, and Ayutthaya.

Japan on the Map

The Fra Mauro map is one of the first Western maps to show the islands of Japan (perhaps after the De Virga world map). A part of Japan, probably Kyūshū, appears below the island of Java, with the label "Isola de Cimpagu" (a misspelling of Cipangu, Marco Polo's name for Japan).

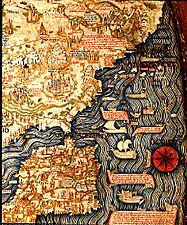

Africa on the Map

The description of Africa on the map is quite accurate for its time.

Some of the islands named near the southern tip of Africa have Arabian and Indian names: Nebila ("celebration" or "beautiful" in Arabic) and Mangla ("fortunate" in Sanskrit). These are usually thought to be the "Islands of Men and Women" mentioned in the Indian Ocean section. According to an old Arabian legend, retold by Marco Polo, one of these islands was only for men and the other only for women. They would only meet once a year to have children. Their exact location was uncertain, and Fra Mauro's proposed spot was just one of many possibilities. Marco Polo himself placed them near Socotra, and other medieval mapmakers put them in Southeast Asia, near Singapore or in the Philippines. These islands are generally believed to be mythical.

The Indian Ocean and Mysterious Journeys

The Indian Ocean is accurately shown as connected to the Pacific Ocean. Several groups of smaller islands, like the Andamans and the Maldives, are also included. Fra Mauro wrote the following inscription near the southern tip of Africa, which he called the "Cape of Diab." It describes an exploration by a ship from the east around 1420:

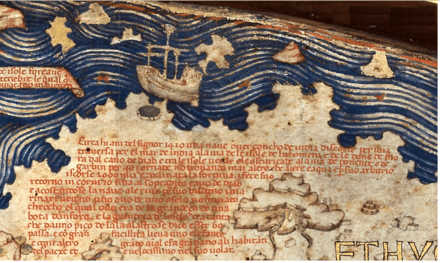

Around 1420 a ship, or junk, from India crossed the Sea of India towards the Island of Men and the Island of Women, off Cape Diab, between the Green Islands and the shadows. It sailed for 40 days in a south-westerly direction without ever finding anything other than wind and water. According to these people themselves, the ship went some 2,000 miles ahead until – once favorable conditions came to an end – it turned round and sailed back to Cape Diab in 70 days.

The ships called junks (lit. "Zonchi") that navigate these seas carry four masts or more, some of which can be raised or lowered, and have 40 to 60 cabins for the merchants and only one tiller. They can navigate without a compass, because they have an astrologer, who stands on the side and, with an astrolabe in hand, gives orders to the navigator.

Fra Mauro explained that he got this information from "a trustworthy source" who traveled with the expedition. This person was possibly the Venetian explorer Niccolò de' Conti, who happened to be in Calicut, India, when the expedition left.

What is more, I have spoken with a person worthy of trust, who says that he sailed in an Indian ship caught in the fury of a tempest for 40 days out in the Sea of India, beyond the Cape of Soffala and the Green Islands towards west-southwest; and according to the astrologers who act as their guides, they had advanced almost 2,000 miles. Thus one can believe and confirm what is said by both these and those, and that they had therefore sailed 4,000 miles.

Fra Mauro also noted that this account of the expedition, along with the story by Strabo about Eudoxus of Cyzicus traveling from Arabia to Gibraltar through the southern ocean in ancient times, made him believe that the Indian Ocean was not a closed sea. This meant Africa could be sailed around its southern end (Text from Fra Mauro map, 11, G2). This knowledge, combined with how the map showed the African continent, probably encouraged the Portuguese to try even harder to sail around the tip of Africa, which they eventually succeeded in doing.

The Americas on the Map

Other than Greenland, the continents of North and South America were unknown to Europeans in 1450. Greenland is included on the map, referred to as Grolanda.

How Big is Earth? The Map's Estimate

Like most scholars in the Middle Ages, Fra Mauro believed the world was a sphere (a ball). However, he drew the continents surrounded by water within the shape of a disc. In one of the texts on the map, he includes an estimate of the Earth's circumference (the distance around it):

Likewise I have found various opinions regarding this circumference, but it is not possible to verify them. It is said to be 22,500 or 24,000 miglia or more, or less according to various considerations and opinions, but they are not of much authenticity, since they have not been tested.

Miglia is Italian for miles. The unit of a mile was invented by the Romans, but it hadn't been standardized yet in 1450. If miglia is taken as the Roman mile, this means the circumference would be about 34,468 kilometers (about 21,417 miles). If miglia is taken as the Italian mile, the stated circumference would be about 43,059 kilometers (about 26,755 miles). The actual distance around the Earth (its meridional circumference) is about 40,008 kilometers (approximately 24,860 English miles). So, Fra Mauro's estimate was quite close!

What Sources Did Fra Mauro Use?

Fra Mauro used many different sources to create his map. He combined existing maps, charts, and old manuscripts with written and spoken stories from travelers. The texts on the map itself mention many of these travel accounts.

Some of the main sources were the stories of the journeys of the Italian merchant and traveler Niccolò de' Conti. Starting in 1419, De Conti traveled all over Asia, reaching as far as China and what is now Indonesia, over a period of 20 years. On the map, many new place names and several exact descriptions were taken directly from de Conti's account. The "trustworthy source" whom Fra Mauro quotes is believed to have been de' Conti himself. The famous travel book by Marco Polo is also thought to be one of the most important sources of information, especially for East Asia.

For Africa, Fra Mauro used recent accounts of Portuguese explorers sailing along the west coast. The detailed information about the southeastern coast of Africa was probably brought by an Ethiopian embassy (a group of representatives) to Rome in the 1430s. Fra Mauro also likely used Arab sources. Arab influence is suggested by the map being oriented with North-South reversed, which was an Arab tradition, seen in the 12th-century maps of Muhammad al-Idrisi.

As Piero Falchetta points out, many geographical facts on Fra Mauro's map don't have clear sources, as similar information isn't found in other preserved Western maps or manuscripts from that time. This can be partly explained by the fact that, besides existing maps and manuscripts, important sources for his map were spoken accounts from travelers – both Venetians and foreigners – who came to Venice from all parts of the then-known world. Fra Mauro himself mentions the importance of these stories in several inscriptions on the map. An even older map, the De Virga world map (1411–1415), also shows the Old World in a way generally similar to the Fra Mauro map, and may have influenced it.

Gallery of the Fra Mauro Map

-

Fra Mauro's Africa (remember, south is at the top, with the "Cape of Diab" marking the southern point)

-

Southeast Asian mainland with the cities of "Scierno", "Pochang" and "Ava" identified as Ayutthaya in Thailand, and Bagan and Inwa in Myanmar.

-

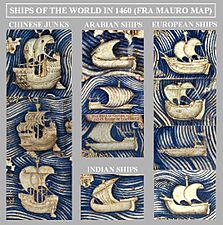

Pictures of a Chinese junk, an Atlantic ship, and a Mediterranean ship from the Fra Mauro map.

-

Ships of the world in 1460, as shown on the Fra Mauro map. Chinese junks are described as very large, three or four-masted ships.

See Also

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |