Tondo (historical polity) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tondo

Tundun |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before 900–1589 | |||||||||||

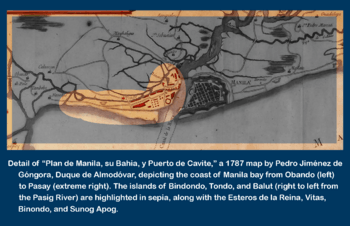

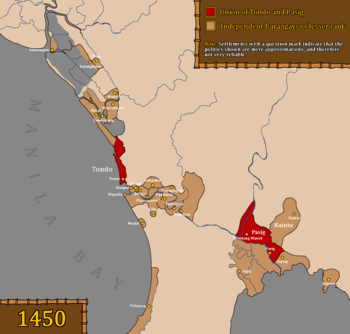

Tondo, Pasig, and other barangays under the influence of Dayang Kalangitan of Pasig in c.1450.

|

|||||||||||

| Capital | Tondo | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Tagalog, Kapampangan, and Classical Malay | ||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||

| Government | Bayan feudal monarchy ruled by a king with the title lakan, consisting of several barangay duchies that are ruled by the respective datu | ||||||||||

| Lakan | |||||||||||

|

• c. 900

|

Unnamed ruler represented by Jayadewa, Lord Minister of Pailah (according to a record of debt acquittance) | ||||||||||

|

• 1450–1500

|

Rajah Lontok and Dayang Kalangitan | ||||||||||

|

• 1521–1571

|

Lakandula | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity to Early modern | ||||||||||

|

• First historical mention, in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription; trade relations with the Mataram Kingdom implied

|

before 900 | ||||||||||

|

• Various proposed dates for the founding of the neighboring Rajahnate of Maynila range as early as the 1200s (see Battle of Manila (1258) and (1365)) to the 1500s (see Battle of Manila (1500))

|

c. 1200s to c. 1500s | ||||||||||

|

• Establishment of regular trade relations with the Ming dynasty

|

1373 | ||||||||||

|

• Territorial conflict with Maynila during the reign of Rajah Matanda's mother

|

c. 1520 | ||||||||||

|

• Fall of Manila

|

1570 | ||||||||||

|

• Battle of Bangkusay Channel

|

1571 | ||||||||||

|

• Attack of Limahong and concurrent Tagalog revolt of 1574

|

1574 | ||||||||||

|

• Discovery of the Tondo Conspiracy, dissolution of indigenous rule, and integration into the Spanish East Indies

|

1589 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Piloncitos, Gold rings, and Barter | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Philippines | ||||||||||

Tondo was an important trading center in early Philippine history. It was a settlement of the Tagalog people located on the northern part of the Pasig River delta, on Luzon island. Tondo and its neighbor, Maynila, controlled the trade of Chinese goods across the Philippine islands. This made them powerful in trade throughout Southeast Asia and East Asia.

Tondo is very important to Filipino historians because it is one of the oldest places in the Philippines with written records. It is mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, the oldest local written document in the Philippines, which dates back to 900 A.D.

After the Spanish arrived in 1570 and defeated the local rulers in 1571, Tondo became part of the Spanish Empire. It lost its independence and is now a district of the modern City of Manila.

Contents

History of Tondo

Tondo was surrounded by water. The Pasig River was to its south, and Manila Bay was to its west. Several smaller rivers and streams also bordered it, like the Canal de la Reina and the Estero de Vitas.

Scholars often call Tondo the "Tondo polity" or "Tondo settlement." Early Tagalog dictionaries described it as a "bayan", which means a "settlement" or "city-state."

Early travelers from countries with kings, like China, Portugal, and Spain, often called Tondo the "Kingdom of Tondo." However, this was a mistake. The Spanish did not have words to describe the complex leadership of Southeast Asian groups. They thought it was a kingdom like theirs. Spanish accounts described Tondo as a smaller "village" compared to the stronger Maynila.

Politically, Tondo was made up of several groups called barangays, each led by a datu. These datus followed the most important leader, called a lakan. In the 1500s, Tondo's lakan was highly respected among the groups around Manila Bay, including Tondo, Maynila, and areas in Bulacan and Pampanga. Historians believe Tondo might have had about 43,000 people when the Spanish arrived in 1570.

The Tagalog people of Tondo had a rich Austronesian culture. This included their own language, writing, religion, art, and music. Their culture was also shaped by trade with other parts of Southeast Asia, especially China, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Majapahit empire. These connections brought Indian cultural influences to the Philippines.

What Does "Tondo" Mean?

There are different ideas about where the name "Tondo" came from. Some think it means "high ground." Others suggest it comes from the name of a river mangrove plant, Aegiceras corniculatum, which was called "tundok" back then.

Tondo's Location and Influence

Tondo was located north of the Pasig River, in an area called Lusong or Lusung. This Old Tagalog name for the Pasig River delta might have come from the word for a large wooden tool used to remove rice husks. This name eventually became the name for the entire island of modern Luzon.

Tondo was shaped like an island, surrounded by water:

- The Pasig River to the south.

- The Canal de la Reina to the southeast.

- The Estero de Vitas to the east and north.

- The Estero de Sunog Apog to the northeast.

- The original shoreline of Manila Bay to the west.

Tondo's territory did not include areas like Maynila, Namayan (modern Santa Ana), or Pandacan, as these had their own leaders.

Culture and Society

The Tagalog people of Tondo had a society influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism. They were led by a lakan, who belonged to the Maharlika class. This was a warrior class, similar to "freemen" or "nobles." In ancient Tagalog society, the highest class was the maginoo, which included the lakan and datus.

Social Structure

The Tagalog groups in Manila, Pampanga, and Laguna had a more complex social system than those in the Visayas. They had more trade and grew wet rice. The Spanish friar Martin de Rada described the Tagalogs as more focused on trade than war.

Historian William Henry Scott described three main classes in Tagalog society in the 1500s:

- The maginoo: The ruling class, including the lakan and datus.

- Freemen: This class included timawa and maharlika.

- Alipin: The slave class, divided into aliping namamahay (who owned their homes and paid tribute) and aliping sa gigilid (who lived in their masters' houses as servants).

The datu or lakan was the chief, but the noble class was called maginoo. Any male from the maginoo class could become a datu through their achievements.

Leadership Structure

Tondo was a large coastal settlement led by several datus, each with their own followers called "dulohan" or "barangay." These datus recognized a main leader, a "paramount ruler" or "paramount datu," called a "lakan." A large coastal settlement with this kind of leadership was called a "bayan."

The leaders of Maynila were called "rajah," and in areas influenced by Islam, they were called "sultans."

The term "barangay" for social groups came from the large ships called balangay. Today, "barangay" is used for the smallest government division in the Philippines, which is different from its original meaning.

Religion

The Tagalog people in Tondo and Maynila had their own beliefs and practices. These came from the early Austronesian peoples, but later mixed with ideas from Hinduism, Mahayana Buddhism, and Islam.

The Tagalogs did not have one name for their beliefs. Scholars today sometimes call it Anitism or "animism."

Tagalog Beliefs

The Tagalog belief system was based on the idea that spirits and supernatural beings, both good and bad, lived in the world. People had to show them respect through worship.

The Tagalogs believed in a creator-god named Bathala. They called him "creator" and "almighty." However, they did not worship Bathala daily. They believed Bathala was too powerful and distant to be bothered with human problems. So, they focused their worship on "lesser" spirits, called "anito," who they believed controlled their daily lives.

These "anito" were seen as Bathala's helpers. People would pray directly to them. Modern writers divide these spirits into "ancestor spirits, nature spirits, and guardian spirits."

Economic Activities

Historians agree that large coastal settlements like Tondo and Maynila were complex. They had specialized jobs and different social classes, which created a demand for special "prestige goods."

People in the Tagalog and Kapampangan regions had jobs like farming, weaving, basket making, metalworking, and hunting. The Maginoo class wanted luxury items like ceramics, fine clothes, and precious stones. This demand led to both local and international trade.

Trade

Tondo and Maynila were important centers for trade. Coastal towns at the mouth of large rivers, like the Pasig River delta, controlled the movement of goods to and from towns further upriver. Tondo and Maynila had agreements that allowed them to control trade throughout the rest of the islands. Tondo's port had a monopoly on Chinese merchant ships. Maynila's ships then sold these goods to other settlements, so much so that Maynila's ships were known as "Chinese" (sinina).

Chinese Goods

The most profitable business for Tondo was selling Chinese goods. These goods arrived in Manila Bay through Tondo's port and were then sent out to the rest of the islands, mainly by Maynila's ships.

Chinese traders came to the Philippines starting in the 7th century. They brought silk, tea, ceramics, and jade stones.

When Chinese ships arrived, the ruler Lakandula would take their sails and rudders until they paid fees. He would then buy all their goods, paying half upfront and the rest the next year. During that time, these goods were traded throughout the islands. This meant other locals could not buy directly from the Chinese, only from Tondo and Maynila, who made a good profit.

Gold as Money

Early Filipinos traded goods using Barter. Later, they started using certain items as money. Gold was common in the islands and was used to make Piloncitos, small gold nuggets that were the earliest coins. They also used gold barter rings.

Piloncitos were tiny, some the size of a corn kernel, weighing from 0.09 to 2.65 grams. They have been found in Mandaluyong, Bataan, the Pasig River banks, and Batangas. The Spanish noted in 1586 that Filipinos were very skilled with gold, teaching their children about it because it was their only money.

Besides Piloncitos, people in Tondo also used gold barter rings. These were larger, ring-shaped gold pieces, similar to early coins from ancient Turkey. They were used in the Philippines until the 16th century.

Agriculture

The people of Tondo were farmers. They grew rice and practiced aquaculture (raising fish and other water animals). Spanish reports from the time of Miguel López de Legazpi mentioned that Luzon had plenty of rice, chickens, wine, and many carabaos, deer, wild boars, and goats. There was also a lot of cotton, colored clothes, wax, honey, and date palms.

Crops

Rice was the main food for Tagalog and Kapampangan groups. Luzon had plenty of rice, which was one reason Legazpi wanted to set up his headquarters in Manila Bay. The Tagalogs had words for at least 22 different kinds of rice.

Root crops like Ubi, Tugi, and Gabi were also grown. Sweet potatoes (now called Camote) were brought later by the Spanish. Millet was also common.

Animals

The Tagalogs also raised ducks, especially around Pateros and Taguig City today. They used methods similar to Chinese ways of hatching eggs. This tradition continues today with the making of balut.

Timeline of Events

Early History

Bruneian Empire (around 1500)

According to stories from Brunei, a city called Selurong (which later became Maynila) was formed around the year 1500.

Some historians say that Manila was likely founded as a trading colony by Brunei around 1500. A royal prince from Brunei married into the local ruling family.

Other Brunei stories say that the Sultanate of Brunei, led by Sultan Bolkiah, attacked Tondo. They then set up Selurong on the other side of the Pasig River. The traditional rulers of Tondo, like Lakandula, kept their titles, but the real power went to the House of Sulayman, the Rajahs of Maynila.

Tondo Joins Brunei (1500)

Tondo became very successful. Around 1500, the Bruneian Empire, under Sultan Bolkiah, connected with Tondo through a royal marriage. Rajah Lontok and Dayang Kalangitan helped establish the city of Selurong (Maynila) on the opposite bank of the Pasig River.

The rulers of Tondo, like Lakandula, kept their titles and property after accepting Islam. However, the main political power shifted to the trading family of Sulayman, the Rajahs of Maynila.

Portuguese Presence (1511 – 1540s)

The Portuguese first arrived in Southeast Asia when they captured Malacca in 1511. They met sailors they called Luções (people from the Manila Bay area). These were the first European accounts of the Tagalog people. The Portuguese described the Luções as a trading people, mostly Muslim, who were "almost one people" with the Malays of Brunei.

The Portuguese writer Tome Pires noted that in their homeland, the Luções had "food, wax, honey, and low-grade gold." They had no king and were led by elders. They traded with groups from Borneo and Indonesia. The language of the Luções was one of the 80 languages spoken in Malacca.

The Luções were skilled sailors. They were involved in wars and politics in the Strait of Malacca, serving in the navies of the Sultans of Ache and Brunei. Some historians believe they were highly skilled naval fighters hired by different fleets.

Portuguese and Spanish accounts from the early 1500s said that Maynila was the same as the "Kingdom of Luzon" (Portuguese: Luçon), and its people were called "Luções."

Conflicts with Maynila (before 1521)

Before 1521, Maynila had a conflict with Tondo. This story comes from Rajah Matanda, as told to members of the Magellan expedition.

Rajah Matanda's mother was the main ruler of Maynila after his father died. Rajah Matanda, then called Prince Ache, grew up with his cousin, who ruled Tondo (thought to be a young Bunao Lakandula).

Ache noticed that his cousin was secretly taking land that belonged to Maynila from his mother. When Ache asked his mother if he could deal with it, she told him to keep the peace. Ache could not accept this, so he left Maynila with some trusted men and went to his "grandfather," the Sultan of Brunei, for help. The Sultan made Ache a commander of his navy.

In 1521, Prince Ache had just won a military battle with the Bruneian navy. He was on his way back to Maynila to confront his cousin when he attacked the remaining ships of the Magellan expedition. Historians think Ache might have wanted to make his fleet even bigger to have more power against his cousin, the ruler of Tondo.

Battle of Manila (May 1570)

The Spanish initially ignored Tondo and its rulers during their conquest of Manila Bay. They focused on Maynila because it had strong defenses, unlike Tondo.

Spanish colonizers first arrived in the Philippines in 1521. But they only reached Manila Bay in 1570. Miguel López de Legazpi sent Martín de Goiti to check out reports of a rich settlement on Luzon.

De Goiti arrived in mid-1570. Maynila's ruler, Rajah Matanda, welcomed him at first. Rajah Matanda had already met the Magellan expedition in 1521. However, talks broke down when another ruler, Rajah Sulayman, arrived. Sulayman was aggressive, saying the Tagalog people would not give up their freedom easily. The Spanish accounts say Tondo's ruler, Lakandula, tried to join the talks, but De Goiti ignored him. He wanted to focus on Maynila because Legazpi wanted to use it as a headquarters since it was already fortified.

By May 24, 1570, talks had failed. The Spanish accounts say their ships fired cannons as a signal for their boats to return. Maynila's rulers saw this as an attack, and Sulayman ordered an attack on the Spanish. The battle was short, and Maynila was set on fire.

The Spanish claimed De Goiti ordered the fire, but historians debate this. It's more likely that Maynila's forces set the fire themselves. Burning their own settlement was a common military tactic to retreat.

De Goiti declared victory and claimed Maynila for Spain. He quickly returned to Legazpi because his forces were outnumbered. Survivors from Maynila likely fled across the river to Tondo and other nearby towns.

Spanish Rule in Maynila (May 1571)

López de Legazpi returned to claim Maynila a year later in 1571. This time, Lakandula was the first to approach the Spanish, followed by Rajah Matanda. Rajah Sulayman was kept away at first, so he would not anger the Spanish.

Legazpi began talking with Rajah Matanda and Lakandula about using Maynila as his base. They reached an agreement by May 19, 1571. Sulayman later joined the talks, apologizing for his actions the previous year, saying they were due to his "youthful passion." It was agreed that Lakandula would join De Goiti on a trip to make friends with other groups in Bulacan and Pampanga, who were allies of Tondo and Maynila. This led to mixed reactions and eventually the Battle of Bangkusay Channel.

Battle of Bangkusay Channel (June 1571)

On June 3, 1571, locals made their last stand against the Spanish in the Battle of Bangkusay Channel. Tarik Sulayman, the chief of Macabebe, refused to ally with the Spanish. He attacked the Spanish forces, led by Miguel López de Legazpi, at the Bangkusay Channel. Sulayman's forces were defeated, and he was killed. The Spanish victory and Legazpi's alliance with Lakandula of Tondo allowed the Spanish to take control of Manila and its nearby towns.

The defeat at Bangkusay ended the resistance against the Spanish among the Pasig River settlements. Tondo, led by Lakandula, gave up its independence and submitted to the new Spanish capital, Manila.

Tondo Conspiracy (1587–1588)

The Tondo Conspiracy of 1587–1588 was a secret plan against Spanish rule. It was led by Tagalog and Kapampangan nobles from Manila and nearby towns. These nobles were the original rulers of their areas. After submitting to the Spanish, they were made to collect taxes or report to Spanish governors.

The plot was led by Agustin de Legazpi, a Tondo chieftain's son and nephew of Lakandula. His cousin, Martin Pangan, was also a leader. The datus swore to fight. However, the uprising failed when Antonio Surabao betrayed them to the Spanish. Agustin de Legazpi was caught and executed. This ended the office of the Paramount Ruler of Tondo.

Other leaders included Magat Salamat, Lakandula's son; Juan Banal, another Tondo prince; and various lords from Pandakan, Polo, Kandaba, Tagig, Bulakan, and Misil.

Notable Rulers of Tondo

Historians have identified several rulers of Tondo from old documents. These include accounts from the Magellan and Legazpi expeditions, and old government records like wills.

| Title | Name | Details | Dates | Main Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senepati | Unnamed | An Admiral and ruler of Tondo mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. He was represented by Jayadewa and pardoned Lord Namwaran and his relatives from their debts. | Around 900 A.D. | Laguna Copperplate Inscription |

| Lakan or Lakandula | Bunao (Lakan Dula) | The last ruler of Tondo to hold the title "Lakan." | Reign: Around 1570s and earlier. Died around 1575. | Legazpi Expedition accounts; Spanish documents |

| Don (Likely a Lakan, but not officially recorded) |

Agustin de Legaspi | The last native ruler of Tondo. He was the son of Rajah Sulayman and was made Paramount Ruler after Lakan Dula died. He was a leader in the 1588 Tondo conspiracy, was caught, and executed by the Spanish. This ended the position of Paramount Ruler. | 1575–1589 | Legazpi Expedition accounts; Spanish documents |

Images for kids

-

An ancient Philippine mortar and pestle.

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Tondó para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Tondó para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |