Maynila (historical polity) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maynila

|

|

|---|---|

| c. 1500–1571 | |

| Capital | Manila |

| Common languages | Old Tagalog, Malay |

| Religion | Islam, Hinduised Tagalog polytheism |

| Government | Monarchy |

| King | |

|

• c. 1500s – c. 1521

|

Salalila |

|

• c. 1521 – August 1572

|

Ache |

|

• 1571–1575

|

Sulayman III |

| Historical era | Middle Ages |

|

• Establishment by King Ahmad, defeating King Avirjirkaya (earliest legendary reference)

|

c. 1500 |

|

• Conversion to Islam

|

c. 1500 |

|

• Death of King Salalila and territorial conflicts with Tondo

|

c. before 1521 |

|

• Marriage between Prince Ache and a princess of Brunei

|

1521 |

|

• Capture and release of Prince Ache by the first Castilian expedition to the Moluccas

|

1521 |

|

• Battle of Manila

|

1570 |

|

• King Ache's allegiance to the Kingdom of the Spains and the Indies

|

1571 |

| Currency | Gold coin |

| Today part of | Philippines |

Maynila was an important historic settlement in the Philippines. It was a "city-state" led by Tagalog people. This old city was located where Intramuros in Manila stands today. It was built on the southern part of the Pasig River delta. Across the river was another important settlement called Tondo.

Maynila was known for being a very diverse and connected place. Its leaders were called "Rajahs," a Malay title similar to a king. In old history books, Maynila is often called the "Kingdom of Maynila." However, these rulers didn't control their land in the same way modern kings do. Their power came from loyalty and social connections, not strict borders.

Some historians think Maynila was also known as the "Kingdom of Luzon." This name might have referred to the entire Manila Bay area. Early stories say Maynila was founded as a Muslim settlement around the 1250s. But the oldest physical evidence of organized settlements dates back to the 1500s. By the 16th century, Maynila was a busy trading hub. It had strong ties with the Sultanate of Brunei and traded a lot with the Ming dynasty from China. Maynila and Tondo together controlled the trade of Chinese goods within the Philippine islands.

By 1570, Maynila was ruled by two main leaders: the older Rajah Matanda and the younger Rajah Sulayman. They also had several lower-ranked rulers called "Datu." This was the situation when Martin de Goiti attacked Maynila in May 1570. This battle ended with Maynila being burned down. It's unclear if the Spanish set the fire or if the locals did it as a defense tactic.

Maynila was partly rebuilt by 1571. That year, Miguel López de Legazpi, Goiti's superior, arrived to claim the city for Spain. After talks with the leaders of Maynila and Tondo, Maynila was declared the new Spanish city of Manila on June 24, 1571. This marked the end of Maynila as an independent city-state.

Contents

- What Does "Maynila" Mean?

- A Look at Maynila's History

- Maynila's Austronesian Roots

- How Maynila Was Governed

- Culture and Daily Life

- Foreign Influences

- Maynila's Economy

- Important Rulers of Maynila

- See also

What Does "Maynila" Mean?

The name Maynilà comes from the Tagalog phrase may-nilà. This means "where indigo is found." Nilà comes from the Sanskrit word nīla, which refers to the indigo plant. This plant is used to make a natural blue dye. The name likely refers to these plants growing in the area. It doesn't mean Maynila was a major indigo dye trading center. That became important much later, in the 1700s.

Some people mistakenly believe the name comes from may-nilad, meaning "where nilad is found." Nilad is a type of shrub-like tree found in mangrove swamps. However, experts say it's unlikely Tagalog speakers would drop the "d" sound from nilad. Also, old documents always called the place "Maynilà," never with a "d" at the end.

Was Maynila the Kingdom of Luzon?

Portuguese and Spanish records from the 1500s suggest that Maynila was the same as the "Kingdom of Luzon." Its people were called "Luções."

For example, a member of the Magellan expedition, Rodrigo de Aganduru Moriz, wrote about capturing Prince Ache in 1521. Prince Ache later became known as Rajah Matanda. He was a commander in the Brunei navy. Aganduru Moriz called him "the Prince of Luzon - or Manila, which is the same." Other expedition members also confirmed this.

Later, when Miguel Lopez de Legaspi arrived, his allies told him to write to Ache, calling him the "King of Luzon." This shows that Maynila and Luzon were often seen as the same place or closely linked.

The name Luzon is thought to come from the Tagalog word lusong. This is a large wooden mortar used to remove the husk from rice. Old milling methods involved pounding rice with a wooden pestle in a lusong. This was hard work but also a way for young people in villages to socialize.

What Was a Bayan?

In the old Tagalog language, large coastal settlements like Tondo and Maynila were called bayan. These were led by a lakan or rajah. Today, the word bayan means "town" or "country." Eventually, it came to refer to the entire Philippines, along with the word bansa (nation).

A Look at Maynila's History

Early Migrations

How Did People Settle Luzon?

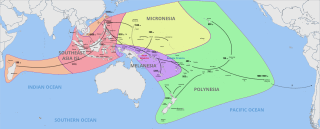

There's a discussion about how the Austronesian culture first arrived in Luzon. Some say they came from mainland Asia, while others believe they came from Southeast Asia. But most scholars agree that these Austronesian people settled in Luzon at least 3,500 years ago. Later, waves of these people spread from the Philippines as far as Easter Island and Madagascar.

Who Were the Tagalogs?

We don't know exactly when the Tagalog and Kapampangan peoples settled around Manila Bay. But linguists believe the Tagalogs came from Northeastern Mindanao or the Eastern Visayas. The Tagalog language is thought to have come from an older "Proto-Philippine language."

How Maynila Was Established

Legends of Rajah Ahmad and Rajah Avirjirkaya

Some old research suggests a settlement in Maynila existed by 1258. It was supposedly ruled by "Rajah Avirjirkaya." This settlement was attacked by a Bruneian commander named Rajah Ahmad. He defeated Avirjirkaya and made Maynila a "Muslim principality." However, historians note that Brunei wasn't Muslim yet in 1258, and the Majapahit empire (which Avirjirkaya was supposedly part of) didn't exist then. So, these dates might be from a later century.

Brunei's Influence in the 1500s

Bruneian stories say that a city called Selurong (later Maynila) was formed around 1500. This story claims that Sultan Bolkiah (1485–1521) of the Sultanate of Brunei attacked Tondo. He then established Maynila as a state controlled by Brunei. The old rulers of Tondo, the Lakandula, kept their titles. But the real power shifted to the House of Soliman, the rulers of Maynila.

Portuguese Accounts of the Luções

In the early 1500s, Portuguese sailors in Malaysia called the Tagalog people from Manila Bay "Luções." These were people from "Lusong" (Luzon).

Important documents from that time mention these Luções. These include writings by Fernão Mendes Pinto and Tomé Pires. Also, the survivors of Ferdinand Magellan's expedition, like Gines de Mafra and Antonio Pigafetta, wrote about them.

Conflicts with Tondo Before 1521

According to stories told by Rajah Matanda to Magellan's expedition members, his father died when he was young. His mother then became the ruler of Maynila. Rajah Matanda, then called Prince Ache, grew up with his cousin, the ruler of Tondo.

Ache noticed his cousin was taking over Maynila's land. When he asked his mother to act, she refused. So, Prince Ache left Maynila with some trusted men. He went to his "grandfather," the Sultan of Brunei, for help. The Sultan made Ache a commander of his navy. Ache was "much feared" in the area, especially by non-Muslim locals who saw the Sultan of Brunei as an enemy.

Prince Ache Captured by Elcano's Expedition (1521)

In 1521, Prince Ache was returning from a military victory. He had just attacked a city in Borneo under orders from the Brunei Sultan. He was on his way to Maynila to confront his cousin. On his journey, he encountered and attacked the remaining ships of the Magellan expedition, then led by Sebastian Elcano. Some historians think Ache wanted to expand his fleet to gain more power against his cousin in Tondo.

Ache was eventually released, likely after a large ransom was paid. One of his slaves, who was not part of the ransom, became a translator for Elcano's expedition.

The Arrival of the Spanish (1570s)

In the mid-1500s, the Manila area was ruled by native rajahs. Rajah Matanda (also known as Ache) and his nephew, Rajah Sulayman, ruled the Muslim communities south of the Pasig River, including Maynila. Lakan Dula ruled non-Muslim Tondo north of the river. These settlements had connections with Brunei, Sulu, and Ternate.

Maynila had a fortress (kota) along the Pasig delta. When the Spanish arrived, they described Maynila as "Kota Selurong." It had a fortress made of rammed earth with wooden walls and cannons. These cannons were made locally. When the Spanish attacked and burned the kota, they built the Christian walled city of Intramuros on its ruins.

Maynila's Austronesian Roots

Like most people in Maritime Southeast Asia, the Tagalogs who founded Maynila were Austronesians. They had a rich culture with their own language, writing, religion, art, and music. This culture existed before influences from China, India, Brunei, and later, European colonizers. Even with the arrival of Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity, the core of Austronesian culture remained. Elements of these new beliefs were often mixed with existing Tagalog traditions.

Austronesian cultures are known for their languages, their love for boats, houses built on stilts, and farming of root crops and rice. Their societies were often led by a "big man" or powerful leader.

How Maynila Was Governed

Social Classes

The Tagalog communities around Manila, Pampanga, and Laguna had a complex social structure. They traded with other parts of Southeast and East Asia. They also grew a lot of rice. Spanish friar Martin de Rada described the Tagalogs as more traders than warriors.

Historian William Henry Scott described three main classes in Tagalog society in the 1500s:

- The maginoo: This was the ruling class, including the Lakan or Rajah and the Datus under them.

- "Freemen": This class included the timawa and maharlika.

- Alipin (slaves): These were further divided into aliping namamahay and alipin sa gigilid.

Leaders and Rulers

Maynila was led by important rulers called "Rajahs." This title came from the Malay language, which itself came from Sanskrit. Even though Maynila is often called a "kingdom," its Rajahs didn't have total control over their land in the modern sense.

Because there weren't many people and farming methods involved moving crops each season, leadership was based on loyalty and social duties. It wasn't about strictly defined land borders.

These leaders gained power by trading and forming family ties with other strong groups. They adopted foreign titles like "rajah" and sometimes claimed to be Muslim. However, early writers noted that most people didn't strictly follow Islamic beliefs. For example, they still ate pork, which is forbidden in Islam.

Culture and Daily Life

Clothing and Appearance

Early Spanish accounts say the Tagalogs used local plants to dye their cotton clothes. Tayum or tagum made a blue dye, and dilao made a yellow dye.

Unlike some other groups in the Philippines, the Tagalogs didn't practice tattooing. In fact, Rajah Sulayman used tattooing as a negative description when he first met the Spanish. He said Tagalogs were not like the "painted" Visayans, meaning they wouldn't be easily tricked.

Religious Beliefs

Historical records show that the Tagalog people, including those in Tondo and Maynila, had their own traditional beliefs. These beliefs came from their Austronesian ancestors. Over time, they mixed in ideas from Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam.

The Tagalogs didn't have a single name for their beliefs. Later scholars called it Anitism, or sometimes animism.

Mixing Old and New Beliefs

One interesting thing was that the top leaders of Tondo and Maynila identified as Muslims. This was also true for some Tagalog sailors met by Portuguese writers. However, reports from that time say that most people were "Muslim by name only." They might avoid pork or blood, but they didn't fully understand Islamic teachings. Scholars believe this was the early stage of Islam spreading. It might have become more widespread if the Spanish hadn't arrived and brought Catholicism.

Historians also note that when Indian cultures influenced Southeast Asia, they didn't erase local beliefs. Instead, Southeast Asians borrowed and adapted ideas, fitting them into their own cultures.

Tagalog Beliefs About the World

The Tagalog belief system was based on the idea that spirits and supernatural beings, both good and bad, lived in the world. People had to show them respect through worship.

Early Spanish missionaries wrote that the Tagalogs believed in a creator-god named Bathala. They called him maylicha (creator) and maycapal (almighty). However, the Tagalogs didn't include Bathala in their daily worship. They believed Bathala was too powerful and distant for everyday concerns. So, they focused their worship on "lesser" gods and spirits who they believed controlled their daily lives.

Since the Tagalogs didn't have one word for all these spirits, Spanish missionaries called them "anito." These spirits were seen as Bathala's helpers. In prayers, people would ask the anito directly for help. Today, these spirits are often grouped as "Ancestor spirits, nature spirits, and guardian spirits."

Foreign Influences

Trade with China, India, and Southeast Asia

The people of Maynila traded with their Asian neighbors, including the Hindu empires of Java and Sumatra. Archeological finds confirm this. Trade with China grew a lot by the 10th century. Contact with Arab merchants was strongest in the 12th century.

How Islam Came to Luzon

Archeological finds show that followers of Islam reached the Pasig River area by 1175. Muslim graves were found at the Sta. Ana burial site.

Islam spread slowly. Traders from Brunei settled in the Manila area in the 1500s. They married locals and kept ties with Brunei. This helped spread Islam to other Muslim centers in Southeast Asia. The Spanish called the Muslims "Moros." However, there's no strong proof that Islam was a major force in the region. Some reports say Muslims lived only in a few villages and were "Muslim in name only."

Maynila's Economy

Historians agree that the large coastal settlements in the Philippines before the Spanish arrived, like Tondo and Maynila, were well-organized. They had specialized jobs and different social classes. This led to a demand for "prestige goods."

Specialized jobs in the Tagalog and Kapampangan regions included farming, weaving, basket making, metalwork, carpentry, and hunting. The maginoo (ruling class) wanted fancy items like ceramics, silk, and precious stones. This demand drove both local and international trade.

Trade Activities

Tondo and Maynila were important trading hubs. They controlled the movement of goods. Coastal towns at river mouths, like Maynila on the Pasig River delta, controlled trade with settlements further upriver. Tondo had a monopoly on Chinese merchant ships arriving in Manila Bay. Maynila's ships then distributed these goods throughout the rest of the islands. Maynila's trading vessels were so well-known that they were sometimes called "Chinese" (sinina) because they carried Chinese goods.

Trading Chinese and Japanese Goods

The most profitable business for Tondo was distributing Chinese goods. These goods arrived at Tondo's port and were then sent out across the archipelago, mostly by Maynila's ships.

Chinese and Japanese people started migrating to Malaya and the Philippines in the 600s. This increased after 1644. These immigrants settled in Manila and other ports. Their trade ships carried silk, tea, ceramics, and jade stones.

According to William Henry Scott, when Chinese and Japanese ships came to Manila Bay, Lakandula would remove their sails and rudders. He would only return them after the ships paid duties. Then, he would buy all their goods himself. He'd pay half the value upfront and the rest when they returned the next year. In between, these goods were traded throughout the islands. This meant other locals couldn't buy directly from the Chinese and Japanese. They had to buy from Tondo and Maynila, who made a good profit.

Farming and Crops

The people of Maynila were farmers. A report from Miguel López de Legazpi's time noted a lot of rice, chickens, and wine in Luzon. There were also many carabaos, deer, wild boars, and goats. People also grew cotton and made colored clothes. They produced wax, honey, and dates.

What Did They Grow?

Rice was the main food for the Tagalogs and Kapampangans. Legazpi wanted to set up his base in Manila Bay because rice was always available there, even with changing rainfall. Old Tagalog dictionaries show words for at least 22 different kinds of rice.

In other parts of the Philippines, root crops were eaten when rice wasn't available. These were also grown in Luzon, but more as vegetables. Ubi, tugi, gabi, and a local root crop called kamoti (not the same as sweet potato) were farmed. Laksa and nami grew wild. Sweet potatoes (now called camote) were brought later by the Spanish.

Millet was also common. The Tagalogs had a word, "dawa-dawa", which meant "millet-like."

Important Rulers of Maynila

Rulers Mentioned in History Books

Here are some rulers of Maynila mentioned in historical documents:

| Title | Name | Description | Dates | Main Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajah | Salalila | Also known as "Rajah (Si) Lela" or "Rajah Sulaiman I." He was a main ruler of Maynila. | Late 1400s or early 1500s (died before 1521) | Spanish family records |

| "Queen" | Name Unknown (Mother of Rajah Ache) |

She ruled Maynila after her husband died. Her rule was during Rajah Matanda's youth. | Late 1400s or early 1500s (ruled around 1521) | Accounts from Magellan expedition members (Rodrigo de Aganduru Moriz, Gines de Mafra, Antonio Pigafetta) |

| Rajah | Ache (Matanda) |

He shared the role of main ruler of Maynila with Rajah Sulayman when the Spanish arrived in the early 1570s. | Born before 1521 – Died August 1572 | Accounts from Magellan (1521) and Legaspi Expeditions (1560s-1570s); Spanish family records |

| Rajah | Sulayman | He shared the role of main ruler of Maynila with Rajah Matanda when the Spanish arrived in the early 1570s. | Around 1571 | Accounts from Legaspi Expedition (early 1570s); Spanish family records |

[†] This term was used by the Spanish; the exact local term is not known.

Legendary Rulers

Some rulers of Maynila are known only through old stories passed down orally. These stories have been written down in various documents.

| Title | Name | Description | Dates | Main Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajah | Avirjirkaya | According to one source, he was a ruler from Majapahit who ruled Maynila. He was defeated in 1258 by Rajah Ahmad from Brunei. | Before 1258 | Genealogy by Mariano A. Henson (1955) |

| Rajah | Ahmad | According to one source, he established Maynila as a Muslim principality in 1258 by defeating Rajah Avirjirkaya. | Around 1258 | Genealogy by Mariano A. Henson (1955) |

See also

- Luções

- Rajah Sulayman

- Battle of Bangkusay Channel

- History of Manila

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- History of the Philippines (Before 1521)

- Hinduism in the Philippines

- Namayan

- Cainta (historical polity)

- Tondo (historical polity)

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |