Datu facts for kids

| Pre-colonial history of the Philippines |

| Barangay government |

| Ruling class (Maginoo, Tumao): Apo, Datu, Lakan, Panglima, Rajah, Sultan, Thimuay |

| Middle class: Timawa, Maharlika |

| Serfs, commoners and slaves (Alipin): Aliping namamahay, Alipin sa gigilid, Bulisik, Bulislis, Horohan, Uripon |

| States in Luzon |

| Caboloan |

| Cainta |

| Ibalon |

| Ma-i |

| Rajahnate of Maynila |

| Namayan |

| Tondo |

| States in the Visayas |

| Kedatuan of Madja-as |

| Kedatuan of Dapitan |

| Rajahnate of Cebu |

| States in Mindanao |

| Rajahnate of Butuan |

| Rajahnate of Sanmalan |

| Sultanate of Sulu |

| Sultanate of Maguindanao |

| Sultanates of Lanao |

| Key figures |

|

| The book of Maragtas |

| Religion in pre-colonial Philippines |

| History of the Philippines |

| Portal: Philippines |

A Datu is a special title for leaders of many native groups across the Philippine archipelago. In the past, these leaders were like chiefs, princes, or even kings. Even today, the title is still used, especially in some parts of the Philippines, but it was much more common a long time ago. The word datu is similar to ratu in other languages spoken in Southeast Asia.

Contents

Who Were the Datus?

In early Philippine history, datus and their close family members were at the very top of society. Only people born into this special group, called maginoo or maharlika, could become a datu. To become a datu, a person also needed to show great skill in war or be an amazing leader.

In big towns near the coast, like those in Manila, Tondo, Cebu, and Sulu, several datus would bring their groups of followers, called barangays, together. This helped them work together better and specialize in different jobs. These datus would then choose the oldest or most respected among them to be a "paramount leader" or "paramount datu".

The titles for these top leaders changed depending on the area. For example:

- Sultan in areas with many Muslim people, like Mindanao.

- Lakan among the Tagalog people.

- Rajah in places that traded a lot with Indonesia and Malaysia.

- Sometimes, they were simply called datu, even if they were the most important one.

Being a true Filipino royal or noble meant you had to be directly related by blood to ancient royal families. Sometimes, people could also become part of a royal family by being adopted.

What Does "Datu" Mean?

The title datu means chief, prince, or monarch across the Philippines. It is still used today, especially in Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan. However, it was used much more in the past, especially in central and southern Luzon, the Visayas, and Mindanao. Other titles still used include lakan in Luzon and sultan or rajah in Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan.

Depending on how important the royal family was, a datu's title could be like a royal prince, or a European duke, marquess, or count. In larger ancient barangays that traded with other Southeast Asian cultures, some datus took the titles of rajah or sultan.

The oldest records mentioning datus are from the 7th century. The word datu is related to the Malay words dato or datuk and the Fijian title ratu.

Datus in History

Before Islam arrived, leaders were called rajah in Manila and datu in other parts of the Philippines.

Datus in Mindanao's Moro and Lumad Societies

In the late 1500s, the Spanish took control of most of Luzon and the Visayas. They converted many people to Christianity. But Spain could not fully conquer Mindanao. This area was home to Muslim groups (called Moros by the Spanish) and non-Muslim native groups, now known as Lumad peoples.

Moro Societies

In traditional Moro societies, sultans were the highest leaders, followed by datus or rajahs. Their power was supported by the Quran, even though these titles existed before Islam arrived. Datus were supported by their tribes. In return for gifts and work, the datu helped in emergencies, settled arguments, and led in wars.

Lumad Societies

At the start of the 1900s, Lumad peoples lived in a large part of Mindanao. But by the 1980s, they made up less than 6% of the population. Many people from the Visayas moved to Mindanao, often helped by the government. This made the Lumads a minority in their own lands.

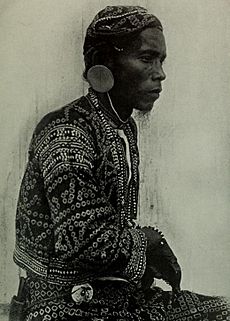

There are 18 main Lumad groups, including the Bagobo, Bukidnon, Manobo, and Tboli. Lumad datus have worked to protect their forests from illegal logging. They continue to be important community leaders in their tribes today.

Datus in the Visayas (Before Spanish Rule)

In the rich and powerful areas of the Visayas, like Panay, Cebu, and Leyte, the datu class was at the very top of society. These areas were never fully conquered by Spain. Instead, Spain made agreements and alliances with them. This social order was divided into three groups.

The kadatuan (members of the datu class) were like the titled lords in Spain. As agalon or amo (lords), datus were respected and supported by their followers, called oripun (commoners). Datus also had special rights from their legal Timawa or vassals (the second group). These Timawa were warriors who served the datu. They did not pay taxes or work in farming. The Boxer Codex called them knights. A Spanish explorer, Miguel de Loarca, said they were "free men, neither chiefs nor slaves".

To keep their bloodline pure, datus usually married only other datus. They often looked for high-ranking brides from other barangays. Sometimes, they would even take them or pay a bride price with gold, slaves, and jewelry. Datus also kept their daughters hidden away for protection and to show their high status. These protected noble women were called binokot. Datus with pure descent (four generations) were called "potli nga datu".

Datus in the Tagalog Region (Before Spanish Rule)

The Tagalog people in Manila, Pampanga, and Laguna had a different and more complex social structure. They traded a lot and farmed rice. A Spanish friar, Martin de Rada, described them as traders more than warriors.

In Tagalog society, the terms datu, lakan, or apo referred to the chief. The noble class, from which datus came, was called the maginoo class. You could be born into the maginoo, but you could also become a datu by achieving great things.

Datus During the Spanish Period

The datu class was called the principalía by the Spanish. This was the noble class of the Philippines. All datus were part of the principalía, whether they ruled or not.

When most of the Philippines became Christian, the datus were still allowed to rule their lands under the Spanish Empire. King Philip II of Spain signed a law in 1594. This law ordered Spanish officials to give native royals and nobles the same respect and special rights they had before becoming Christian. Their lands became self-ruled areas that paid tribute to the Spanish Empire.

Filipino royals and nobles were part of the principalía. This group had a birthright to be respected and obeyed by others. With Spanish recognition, they were given the title Don or Doña. This was a special title in Europe for nobles.

The gobernadorcillos (elected leaders, often Christianized datus) were very important. They managed the towns and acted as judges. They had many rights and powers.

By the end of the 1500s, the idea of Filipino royalty or nobility changed into a mixed, Spanish-influenced, and Christianized nobility called the principalía. These old royal and noble families continued to rule their lands until the end of Spanish rule. In distant areas, where Spanish control was weaker, leaders were still chosen by family inheritance. These areas remained traditional societies where people greatly respected the principalía.

The principalía was larger and more powerful than the old native nobility. It helped create a system where a few powerful families ruled for over 300 years. The Spanish government did not allow foreigners to own land, which helped this system grow. Many Spanish and foreign traders married rich native nobles. Their children, called mestizos, later became powerful in government and the principalía.

What Datus Did (Political Roles)

Datus were important leaders. They were the main political authorities, war leaders, and judges. They often owned the farm products and sea resources in their area. They supported skilled workers, managed trade, and helped organize resources for their communities.

Historians and anthropologists say that while datus were noble and aristocratic, their power was not like that of absolute kings. Their control over land came from their leadership of the barangay. In some areas, especially Luzon, the idea of ruling was not seen as a "divine right" (given by God). A datu's position also depended on the agreement of the noble Maginoo class in the barangay. Even if the position was inherited, the maginoo could choose someone else from their class if that person was a better war leader or manager.

Antonio de Morga, in his book Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, explained that early Philippine datus had limited power: "There were no kings or lords throughout these islands who ruled over them as in the manner of our kingdoms and provinces; but in every island, and in each province of it, many chiefs were recognized by the natives themselves. Some were more powerful than others, and each one had his followers and subjects, by districts and families; and these obeyed and respected the chief. Some chiefs had friendship and communication with others, and at times wars and quarrels... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay."

Paramount Datus

The term "paramount datu" means the highest-ranking political leader in the largest communities or groups of communities in early Philippine history. This was seen in places like Maynila, Tondo, Panay, Cebu, and Sulu.

Different cultures used different titles for their most senior datu:

- In Muslim areas like Sulu and Cotabato, the top ruler was a sultan.

- In Tagalog areas, the title was lakan.

- In communities that traded with Indianized groups, the top ruler was a rajah.

- Among the Subanon people, the most senior thimuay was called the thimuay labi.

- In some parts of the Visayas and Mindanao, the top ruler was still called a datu, but everyone knew they were the most senior.

Nobility of Datus

The noble nature of datus and their families is shown in old stories, was recognized by foreigners, and is supported by modern studies. The position of datu was often passed down through family, but not always. Only someone from the aristocratic class could become a datu. Chinese traders and Spanish colonizers described datus as sovereign princes. They even called them "kings" at first, though they later learned that datus did not have absolute power over their people.

Native Ideas of Nobility

Filipinos have always believed that individuals are deeply connected to their community. This idea shaped the roles and duties of people in society. Social life was based on the idea that people had different levels of importance and duties to each other.

In some places, like the Visayas, old stories said that datus and the noble class were at the top of a social order chosen by a higher power. These stories said that while everyone was created by a deity, the actions of these creations determined their descendants' social position. This idea of social organization still affects Philippine society today.

Becoming Part of the Noble Class

A datus power and influence came mainly from being recognized as part of the noble class. A datus right to lead was not just from birth. It also depended on their personal charm, skill in war, and wealth.

Passing Down the Title

The datu office was usually passed down through family. Even if it wasn't a direct family member, only another noble could take the position. In large settlements where many datus lived close by, the "paramount datu" was chosen more democratically by the other datus. But even this top position was often inherited.

Antonio de Morga noted this in his book: "These principalities and lordships were inherited in the male line and by succession of father and son and their descendants. If these were lacking, then their brothers and collateral relatives succeeded... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay."

Wealth and Status

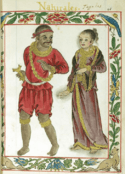

Since the cultures in the Visayas, northern Mindanao, and Luzon were influenced by Hindu and Buddhist traditions, the datus in these areas shared many customs with royals and nobles in other Southeast Asian places. They dressed and decorated themselves with gold and silk. The amount of gold and slaves a prince had showed how great and noble he was. The first Westerners who came to the Philippines noticed that almost every native person had gold chains and other gold items.

Foreign Recognition

The Spanish colonizers in the 1500s recognized the nobility of the aristocratic class in early Philippine societies. De Morga, for example, called them "principalities." After the Spanish government was set up, they continued to recognize the descendants of old datus as nobles. They gave them positions like Cabeza de Barangay. Spanish kings recognized their noble background.

Were Datus "Monarchs"?

Early Misunderstandings

When travelers from countries with kings came to the Philippines, they often called the Philippine rulers "monarchs" or "kings." For example, Chinese traders called the ruler of Ma-i a huang, meaning king.

The Spanish explorers in the 1520s and 1570s also first called paramount datus (like lakans and rajahs) "kings." But they stopped using this term when they visited areas like Bulacan and Pampanga in 1571. They realized that the datus there did not have to obey the paramount datus of Tondo and Maynila. The leaders of Tondo and Maynila even explained that there was "no single king over these lands."

Historians say this misunderstanding was natural. Both the Chinese and Spanish came from cultures with powerful emperors or kings. They tended to see the world through their own ideas of absolute rule.

The idea of a sovereign monarchy was not unknown to early Filipinos, as they traveled and traded widely. The Tagalogs, for example, had the word "hari" for a monarch. However, they usually used "hari" for foreign kings, like those from Javanese kingdoms, not for their own leaders. Words like "Datu," "rajah," and "lakan" were unique terms for their local rulers.

How "Royalty" is Used Today

Even though early Philippine datus were not "sovereign" in the political sense, they later came to be called kings or monarchs in popular stories. This happened because European literature was introduced during the Spanish colonial period.

Playwrights during the Spanish era did not have exact words to describe old Philippine leadership. So, they started using European ideas like "king" or "queen." Most Filipinos, even before colonization, saw political power as something separate from ordinary people. So, this new idea of royalty was accepted. The difference between a monarchy (a political system) and being part of a noble family was lost.

Today, the popular idea of monarchy is based on Filipinos seeing "great men" as separate from ordinary people, rather than the strict rules of monarchies. Datus, lakans, rajahs, and sultans are often called kings or monarchs in a general sense, especially in 20th-century Philippine textbooks.

However, modern historians and anthropologists now highlight the technical differences between these ideas.

Honorary Datus

The title "honorary datu" has been given to foreigners and non-tribe members by local tribal leaders. In the past, some of these titles came with legal benefits. For example, in 1878, the Sultan of Sulu made Baron de Overbeck an honorary Datu Bendahara and rajah of Sandakan, giving him power over the people.

In the Philippines, the Spanish did not give honorary titles. Instead, they created noble titles over conquered lands to reward high Spanish officials. These titles are still used in Spain by the descendants of the original holders.

Different tribes in the Philippines have their own customs for giving local honorary titles. These titles fit the traditional social structures of those native peoples. In parts of the Philippines not influenced by Spanish or Islamic rule, there are other types of societies that do not have strict social classes.

Datus Today

Today, people who claim the old royal or noble title of datu are of two types:

- Descendants of Muslim rulers in Mindanao who were not fully controlled by Spain (e.g., the Sultanate of Jolo). They still use their ancestors' titles.

- Descendants of the Christianized datus and rajahs (the principalía). Their noble status was recognized by the Spanish Empire. These include descendants of the last datus of Palawan, Panay, Cebu, and Manila. These descendants are now often among the wealthy, educated, and political leaders in Filipino society. They often have ancestors who used the titles Don or Doña.

The Philippine Constitution and Datus Today

The 1987 Constitution of the Philippines clearly states that no new royal or noble titles can be created or used. So, any "honorary datu" titles given by tribes to foreigners or non-tribe members are just local awards. They are not legally binding.

However, the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997 protects the unique situation of tribal minorities and their traditional social structures. This law allows members of native tribes to be given traditional leadership titles, including datu. This must be done according to the law's rules.

The National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) states:

- Native groups have the only right to give leadership titles like Bae, Datu, Baylan, and Timuay to their members, following their own customs.

- To prevent fake titles, native groups can give a list of their recognized traditional leaders to the NCIP. The NCIP will check this list and keep a national record.

- Only recognized, registered leaders can issue certificates of tribal membership. The NCIP must confirm these certificates.

Based on this, the current use of the title datu for new tribal leadership positions does not mean nobility, which is forbidden by the Constitution.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Datu para niños

In Spanish: Datu para niños

- Hinduism in the Philippines

- History of the Philippines (before 1521)

- Rajahnate of Maynila

- Namayan

- Tondo (historical polity)

- Malay styles and titles

- Rajahnate of Butuan

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Recorded list of Datus in the Philippines

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Taytay, Palawan

- Non-sovereign monarchy

- Federal monarchy

- Philippine shamans

- Maharlika

- Bagani

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |