History of the Philippines facts for kids

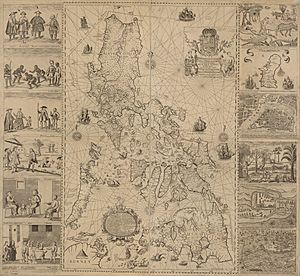

The history of the Philippines is a long and exciting journey, starting from when the first humans arrived in the islands about 709,000 years ago! An ancient human species called Homo luzonensis lived on Luzon Island at least 67,000 years ago. The oldest known modern human remains were found in Tabon Caves, Palawan, dating back about 47,000 years. The first people to settle in the Philippines were groups called Negritos. Around 3000 BC, seafaring people known as Austronesians, who are the ancestors of most Filipinos today, sailed south from Taiwan and settled the islands.

Over time, these groups grew into different communities and kingdoms. Some of these places, especially those near big rivers, became very organized and powerful. Important early settlements included the areas that are now Manila, Tondo, Pangasinan, Cebu, Panay, Bohol, Butuan, Cotabato, Lanao, Zamboanga, and Sulu. There were also other kingdoms like Ma-i, possibly located in Mindoro or Laguna.

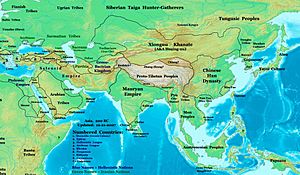

These early kingdoms were influenced by cultures from Islam, India, and China. Islam came from Arabia, while Indian Hindu-Buddhist ideas, languages, and literature arrived through trade and expeditions. Some kingdoms also became allies of China, sending tributes. These small maritime states were very active traders from the 1st millennium AD, exchanging goods with places like China, India, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Other smaller settlements, called barangays, were independent but often allied with these larger states. These states sometimes joined or were influenced by big Asian empires like the Ming Dynasty, Majapahit, and Brunei, or they fought against them.

The first Europeans to visit were part of Ferdinand Magellan's expedition, landing on Homonhon Island on March 17, 1521. Magellan was later killed in a battle against Lapulapu, a chief from Mactan. Spanish rule in the Philippines began when Miguel López de Legazpi arrived from Mexico on February 13, 1565. He set up the first lasting Spanish settlement in Cebu. Most of the islands then came under Spanish control, forming the first unified country known as the Philippines. During Spanish rule, Christianity was introduced, along with new laws and the oldest modern university in Asia, the University of Santo Tomas. The Philippines was first governed by Spain through Mexico, and later directly by Spain.

Spanish rule ended in 1898 after Spain lost the Spanish-American War. The Philippines then became a territory of the United States. U.S. forces fought against a revolution led by Emilio Aguinaldo. The United States set up a government to rule the Philippines, and in 1907, an elected Philippine Assembly was created. The U.S. promised independence, and the Philippine Commonwealth was formed in 1935 as a step towards full independence in 10 years. However, in 1942, during World War II, Japan occupied the Philippines. U.S. forces defeated the Japanese in 1945. The Treaty of Manila in 1946 finally made the Philippines an independent republic.

Contents

- Prehistory: The Earliest Times

- Precolonial Period: Independent Kingdoms (900 to 1565 AD)

- First Written Records

- The Kingdom of Tondo

- The Kingdom of Cainta

- Confederation of Namayan

- Caboloan (Pangasinan)

- The Nation of Ma-i

- The Nation of Sandao

- The Nation of Pulilu

- Visayan Raids on China

- Kedatuan of Madja-as

- The Rajahnate of Cebu

- The Rajahnate of Butuan

- The Rajahnate of Sanmalan

- Struggle Against Hindu Majapahit

- The Sultanate of Sulu

- The Sultanate of Maguindanao

- The Sultanate of Lanao

- The Bruneian Empire and Islam's Spread

- The Lucoes: Filipino Seafarers and Warriors

- Rise and Fall of the Dapitan Kedatuan

- Rivalries Among Kingdoms

- Spanish Rule (1565–1898): A New Era

- The First Philippine Republic (1899–1901)

- American Rule (1898–1946)

- The Third Republic (1946–1965)

- Marcos Era (1965–1986)

- Fifth Republic (1986–Present)

- Corazon Aquino's Administration (1986–1992)

- Fidel V. Ramos's Administration (1992–1998)

- Joseph Estrada's Administration (1998–2001)

- Gloria Macapagal Arroyo's Administration (2001–2010)

- Benigno Aquino III's Administration (2010–2016)

- Rodrigo Duterte's Administration (2016–2022)

- Bongbong Marcos's Administration (2022–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

Prehistory: The Earliest Times

Evidence like stone tools and animal fossils found in Rizal, Kalinga, show that early humans lived in the Philippines as far back as 709,000 years ago. Researchers found 57 stone tools near rhinoceros bones with cut marks, suggesting that early humans used tools to get marrow from bones. The oldest human fossil, a foot bone from Callao Man in Cagayan, is about 67,000 years old. This and the Angono Petroglyphs in Rizal suggest that people lived here before the Negritos and Austronesian-speaking people arrived. The Callao Man remains and other bones found in Callao Cave were later identified as a new human species called Homo luzonensis. For modern humans, the Tabon Man remains are still the oldest known, at about 47,000 years old.

The Negritos were early settlers, but we don't know exactly when they arrived. Later, people who spoke Malayo-Polynesian languages, a branch of the Austronesian language family, came. The first Austronesians reached the Philippines between 3000–2200 BC, settling in the Batanes Islands and northern Luzon. From there, they quickly spread to the rest of the Philippine islands and Southeast Asia. They also sailed further east to the Northern Mariana Islands around 1500 BC. These Austronesians mixed with the earlier Negritos, creating the diverse Filipino ethnic groups we see today.

The most accepted idea about how the islands were populated is the "Out-of-Taiwan" model. This theory says that Austronesian people expanded during the Neolithic Age (New Stone Age) through sea migrations. They started from Taiwan and spread across the Indo-Pacific, reaching as far as New Zealand, Easter Island, and Madagascar. These Austronesians originally came from rice-farming civilizations in southeastern China, near the Yangtze River delta. These include cultures like Liangzhu, Hemudu, and Majiabang. This theory connects Austronesian language speakers in a common family, including indigenous Taiwanese, island Southeast Asians, and Polynesians. Besides language and genetics, they also share cultural traits like special boats (multihull and outrigger boats), tattooing, rice farming, and ancestor worship. They also brought domesticated animals like dogs, pigs, and chickens, and plants like yams, bananas, and coconuts.

A 2021 study of 115 indigenous communities found at least five different waves of early human migration. Negrito groups, whether in Luzon or Mindanao, might have come from one wave and then separated, or from two different waves. This likely happened after 46,000 years ago. Another Negrito migration entered Mindanao after 25,000 years ago. Two early East Asian waves were also found. One is seen strongly among the Manobo people in Mindanao, and the other among the Sama-Bajau people in the Sulu archipelago. These migrations happened after 15,000 years ago and 12,000 years ago, around the end of the last ice age. Austronesians, from Southern China or Taiwan, came in at least two waves. The first, between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago, brought ancestors of groups living around the Cordillera Central mountains. Later migrations brought other Austronesian groups, along with farming, and their languages replaced older ones. Newcomers usually mixed with existing populations. Trade with India around 2,000 years ago also left some South Asian genetic traces in Sama-Bajau communities. There's also evidence of Papuan migration to Southeast Mindanao.

By 1000 BC, people in the Philippines had developed into four main types:

- Tribal groups: Like the Aetas and Mangyan, who hunted and gathered in forests.

- Warrior societies: Like the Isneg and Kalinga, who had social rankings and practiced ritualized warfare in the plains.

- Petty plutocracy: The Ifugao Cordillera Highlanders, who lived in the mountains of Luzon and had wealthy leaders.

- Harbor principalities: Civilizations that grew along rivers and coasts, involved in sea trade.

It was also during this time that early metalworking arrived in Southeast Asia through trade with India.

Around 300–700 AD, islanders traveling in boats called balangays began trading with Indianized kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago and East Asian areas. They adopted ideas from both Buddhism and Hinduism.

Maritime Jade Road: An Ancient Trade Route

The Maritime Jade Road was an important trade route for ancient Filipinos. It started between the Philippines and Taiwan, then expanded to Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand. Tools and ornaments made from white and green jade, like adzes, chisels, and earrings, have been found in many Philippine archaeological sites since the 1930s. Tens of thousands were found in one site in Batangas. This jade came from Taiwan and is also found in other parts of Southeast Asia. These artifacts show that ancient societies in Southeast Asia communicated and traded over long distances.

The Maritime Jade Road was one of the largest sea-based trade networks for a single material in the ancient world. It existed for 3,000 years, from 2000 BCE to 1000 CE. This trade route was active during a time of great peace, lasting 1,500 years (500 BCE to 1000 CE). During this peaceful time, no ancient burial sites showed signs of violent death or mass burials. This suggests a peaceful period in the islands. Signs of violent deaths only appear in burials from the 15th century, likely due to new ideas of expansionism from India and China. When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, they found some warlike groups, whose cultures had already been influenced by these newer ideas.

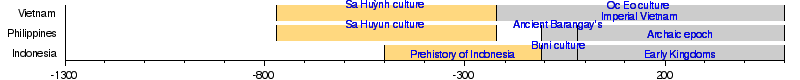

The Sa Huỳnh Culture: Early Connections

The Sa Huỳnh culture, based in what is now Vietnam, had a large trade network. Sa Huỳnh beads were made from materials like glass, carnelian, and gold, most of which were not found locally. This means they were imported. Bronze mirrors from the Han dynasty in China were also found in Sa Huỳnh sites.

On the other hand, Sa Huỳnh ear ornaments have been found in archaeological sites in Central Thailand, Taiwan, and the Tabon Caves in Palawan, Philippines. The artifacts in Kalanay Cave in Masbate, part of the "Sa Huỳnh-Kalanay" pottery group, are dated from 400 BC to 1500 AD. The Maitum anthropomorphic pottery in Sarangani Province, Mindanao, is from around 200 AD.

However, recent research suggests that the pottery in Kalanay Cave is different from Sa Huỳnh but similar to sites in Hoa Diem, Central Vietnam, and Samui Island, Thailand. New estimates date the Kalanay Cave artifacts much later, to 200–300 AD. This shows how cultures influenced each other across Southeast Asia.

-

-

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Prehistoric (or Proto-historic) Iron Age Historic Iron Age

-

Precolonial Period: Independent Kingdoms (900 to 1565 AD)

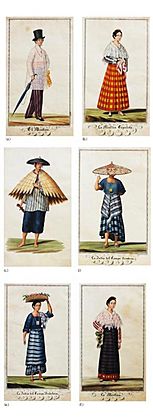

This time before the Spanish arrived was marked by many independent states, each with its own history, culture, leaders, and government. Records from Southern Liang show that people from the kingdom of Langkasuka (in Thailand) were wearing cotton clothes made in Luzon as early as 516–520 AD.

By the 1300s, many large coastal settlements became important trading centers. During this "Barangay Phase" of history, communities were very mobile, sometimes moving from land settlements to fleets of boats and back again. Political power was often based on strong leaders and changing alliances, with constant interactions, both peaceful and warlike, between different groups.

There is not much archaeological proof that early Philippine groups interacted with the Srivijaya empire, but there is strong evidence of extensive trade with the Majapahit empire. Indian cultural influences, like words and religious practices, likely came through trade with the Hindu Majapahit empire between the 10th and early 14th centuries. The Philippines was at the edge of what is called the "Greater Indian cultural zone."

Early Philippine communities usually had a three-level social structure. While different cultures used different names, there was always a noble class, a class of "freemen," and a class of dependent workers or debtors called "alipin" or "oripun." Leaders from the noble class were called "Datu." They led independent social groups called "barangay" or "dulohan." When several barangays joined together, a more respected datu would be recognized as a "paramount datu," sometimes called a Lakan, Sultan, or Rajah. By the 14th to 16th centuries, wars between kingdoms increased, and the population density across the islands was low.

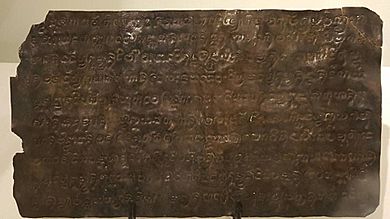

First Written Records

During the time of the Pallava dynasty in South India and the Gupta Empire in North India, Indian culture spread to Southeast Asia and the Philippines, leading to the creation of Indianized kingdoms.

The oldest Philippine document found so far is the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, dated 900 AD. Written in Kawi script, it shows that a debt was cleared for a person named Namwaran and his children by the ruler of Tondo. This document is the earliest proof of mathematics being used in precolonial Philippine societies. It shows a system of weights and measures for gold and knowledge of astronomy. The Sanskrit words and titles in the document show that the culture in Manila Bay was a mix of Hindu and Old Malay, similar to cultures in Java, Malaysia, and Sumatra at that time.

There are no other major documents from this period until the late 16th century's Doctrina Christiana, written in both native Baybayin script and Spanish. Other artifacts with Kawi script and Baybayin have been found, like an ivory seal from Butuan (10th–14th centuries) and the Calatagan pot with Baybayin writing (not later than early 16th century).

Around the year 1000, several sea-based societies existed in the islands, but there was no single country covering the entire Philippines. Instead, there were many semi-independent barangays (settlements from villages to city-states) ruled by competing leaders like datus, wangs, rajahs, sultans, or lakans. There were also highland farming societies led by "petty plutocrats." Some of these included:

- The Kingdom of Maynila

- The Kingdom of Taytay in Palawan

- The Chieftaincy of Coron Island

- The Confederation of Namayan

- The polities of Tondo and Cainta

- The Sinitic wangdom of Pangasinan

- The nation of Ma-i and its smaller states of Sandao and Pulilu

- The Kedatuans of Madja-as and Dapitan

- The Indianized rajahnates of Sanmalan, Butuan, and Cebu

- The sultanates of Maguindanao, Lanao, and Sulu

Some of these areas were part of larger Malay empires like Srivijaya, Majapahit, and Brunei.

The Kingdom of Tondo

The earliest historical record mentioning local kingdoms is the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. It talks about the Tagalog kingdom of Tondo (before 900–1589 AD) and other nearby settlements, as well as a place in Mindanao and a temple in Java. While the exact political connections are unclear, this artifact shows that there were political links within and between regions as early as 900 CE. By the 1500s, when Europeans arrived, Tondo was led by a "Lakan" (paramount ruler). It had become a major trading center, sharing control with the Rajahnate of Maynila over trade of Ming dynasty products throughout the islands. This trade was so important that the Chinese Yongle Emperor appointed a Chinese governor to oversee it.

Since at least 900 AD, this sea-based kingdom in Manila Bay thrived through active trade with Chinese, Japanese, Malays, and other Asian peoples. Tondo was the capital and center of power, led by kings called "Lakan" from the noble warrior class (Maharlika). At its peak, it controlled a large part of what is now Luzon, from Ilocos to Bicol, becoming the largest precolonial state. The Spanish called their nobles Hidalgos.

The people of Tondo had a culture that was mostly Hindu and Buddhist. They were also good farmers and lived by farming and raising fish. Tondo became one of the wealthiest kingdoms in precolonial Philippines due to strong trade and connections with nations like China and Japan.

Because of its good relations with Japan, the Japanese called Tondo "Luzon." A famous Japanese merchant even changed his last name to Luzon. Japan's interaction with Philippine states goes back to the 700s when Austronesian people settled in Japan and traded with their kin to the South. Japan also imported Mishima ware made in Luzon. In 900 AD, a lord-minister named Jayadewa presented a document forgiving a debt to Lady Angkatan and her brother Bukah, children of Namwaran. This is described in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription.

The Chinese also mentioned a kingdom called "Luzon." This is thought to refer to Maynila, as Portuguese and Spanish accounts from the 1520s said "Luçon" and "Maynila" were the same. However, some historians argue that "Luçon" might have referred to all Tagalog and Kapampangan kingdoms around Manila Bay.

The Kingdom of Cainta

The Kingdom of Cainta, in Rizal province, was a fortified settlement. The Pasig River flowed through its middle, and a moat surrounded its log walls and stone defenses, which were armed with native cannons called Lantakas. The city itself was protected by thick bamboo. When the Spanish arrived, it was ruled by a chief named Gat Maitan.

Confederation of Namayan

Namayan was a group of local barangays that joined together. Local stories say it was strongest in 1175. Archaeological finds in Santa Ana, Namayan's old center, show the oldest continuous human settlement among the Pasig River kingdoms, even older than artifacts found in Maynila and Tondo.

Caboloan (Pangasinan)

Places in Pangasinan, like Lingayen Gulf, were mentioned as early as 1225. Lingayen, then known as Li-ying-tung, was listed in a Chinese record as a trading place. In northern Luzon, Caboloan (Pangasinan) (around 1406–1576) sent envoys to China between 1406–1411 as a tributary state and also traded with Japan. Chinese records of this kingdom, called Feng-chia-hsi-lan (Pangasinan), began when its first king, Kamayin, sent gifts to the Chinese Emperor. This state covered the current province of Pangasinan. It was locally known as Luyag na Kaboloan, with Binalatongan as its capital, and thrived around the same time as the Srivijaya and Majapahit empires in Indonesia. The Luyag na Kaboloan expanded its territory to what are now Zambales, La Union, Tarlac, Benguet, Nueva Ecija, and Nueva Vizcaya. Pangasinan was fully independent until the Spanish conquest.

In the 16th century, the Spanish called Pangasinan the "Port of Japan." Locals wore native clothes and Japanese and Chinese silks. Even common people wore Chinese and Japanese cotton. They also blackened their teeth and disliked the white teeth of foreigners, comparing them to animals. They used porcelain jars common in Japanese and Chinese homes. Japanese-style gunpowder weapons were also found in naval battles there. Traders from Asia came to trade for gold, slaves, deerskins, and other local products. Besides a larger trade network with Japan and China, their culture was similar to other Luzon groups to the south.

The Nation of Ma-i

The Arab historian Al Ya'akubi wrote that in the 800s, the kingdoms of Muja (Brunei) and Mayd (Ma-i) competed militarily with the Chinese Empire. Volume 186 of the official history of the Song dynasty describes the kingdom of Ma-i (around before 971 – after 1339). Song dynasty traders visited Ma-i yearly, describing its geography, trade products, and the honest behavior of its rulers. Because the descriptions of Ma-i's location are unclear, some scholars believe it was in Bay, Laguna, while others think it was on Mindoro Island. This Buddhist kingdom traded with Ryukyu and Japan. William Henry Scott said that unlike other Philippine kingdoms that needed Chinese support for trade, Ma-i was powerful enough not to need to send tributes to China.

The Nation of Sandao

Sandao, also known as Sanyu, was a pre-Hispanic Filipino nation mentioned in Chinese records. It occupied the islands of Calamian, Palawan, and Pulihuan (near Manila). In the Chinese Gazetteer Zhufan zhi (1225), it was described as a smaller state under the more powerful nation of Ma-i, centered in nearby Mindoro.

The Nation of Pulilu

Pulilu was a pre-Hispanic kingdom centered at Polillo, Quezon. It was mentioned in the Chinese Gazetteer Zhufan zhi (1225). It was politically connected to Sandao in the Calamianes, which was a smaller state under Ma-i in Mindoro. Its people were described as warlike and prone to raiding. The sea around this area was full of sharp coral reefs. Red and blue coral were produced here, but they were hard to find. Pulilu had similar customs and trade products to Sandao. Its main export was rare corals.

Visayan Raids on China

In the 13th century, Chinese historian Chao Ju-Kua wrote about raids by the Pi-sho-ye on port cities in southern China between 1174–1190 AD. He believed they came from the southern part of Taiwan. Later historians identified these raiders as Visayans from the Visayas islands. Historian Efren B. Isorena concluded that these raiders were most likely people from Ibabao (the precolonial name for the eastern coast of Samar).

Kedatuan of Madja-as

One theory suggests that in the 11th century, ten exiled datus from the collapsing Srivijaya empire, led by Datu Puti, migrated to the central Philippines. They were fleeing from Rajah Makatunaw of Borneo. They bought Panay Island from Negrito chief Marikudo and established a group of states called Madja-as, centered in Aklan. They then settled the surrounding Visayas islands. This story comes from Pedro Monteclaro's book Maragtas. However, there are different dates for Rajah Makatunaw in Chinese texts. Madja-as was supposedly founded on Panay Island. Its people were loyal warriors who fought against Hindu and Islamic invaders from the west. This group of states reached its peak under Datu Padojinog, who extended its power over most of the Visayas islands. They often made pirate attacks against Chinese ships.

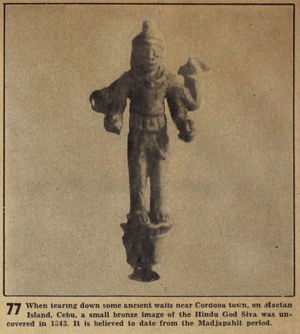

The Rajahnate of Cebu

The Rajahnate of Cebu was a precolonial state founded by Sri Lumay, also known as Rajamuda Lumaya. He was a half-Malay, half-Indian prince from the Hindu Chola dynasty. He was sent to establish a base but rebelled and created his own independent kingdom. The Chinese called the Rajahnate of Cebu "Sokbu." The Indianized royalty of Cebu ruled the native Cebuano people from their capital, Singhapala, which means "Lion City" in Tamil-Sanskrit. This kingdom fought against slave traders from Maguindanao and had an alliance with the Rajahnate of Butuan and Kutai in South Borneo. It was later weakened by an uprising led by Datu Lapulapu. The kingdom had diplomatic ties with Thailand, as Ferdinand Magellan's expedition noted a ship from Siam (Thailand) that had landed in Cebu with tributes for Rajah Humabon.

The Rajahnate of Butuan

The official history of the Song dynasty mentions the Rajahnate of Butuan (around before 1001–1756) in northeastern Mindanao. It was the first kingdom from the Philippines to send a tribute mission to the Chinese empire on March 17, 1001 CE. Butuan became important under Rajah Sri Bata Shaja. In 1011, Rajah Sri Bata Shaja, the ruler of the Indianized Rajahnate of Butuan, known for its goldwork, sent a trade envoy to the Chinese Imperial Court. He demanded equal diplomatic status with other states. This request was approved, opening direct trade with Butuan and the Chinese Empire. This reduced the trade monopoly previously held by Tondo and the Champa civilization. The Butuan Silver Paleograph proves this kingdom existed. Researcher Eric Casino believes the name of the first Rajah mentioned in Chinese records, Rajah Kiling, is Indian, as "Kiling" refers to people from India. The Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals) of Malaysia also refers to "Keling" as immigrant people from India.

The Rajahnate of Sanmalan

At the same time as Butuan, the Rajahnate of Sanmalan emerged. Sanmalan was a precolonial Philippine kingdom in what is now Zamboanga City. The Chinese recorded in 982 that its Rajah, Chulan, sent a tribute through ambassador Ali Bakti. In the 1200s, the Chinese chronicle Zhufan zhi recorded that Sanmalan changed from a trading center to a slave-raiding state. Zamboanga began warring and raiding neighboring kingdoms in Borneo, the Philippines, Sulawesi, and Ternate for slaves to sell in Java.

Struggle Against Hindu Majapahit

During the 1300s, Chinese records reported that Brunei invaded or controlled Sarawak, Sabah, and the Philippine kingdoms of Butuan, Sulu, and Ma-i (Mindoro). These Philippine kingdoms later regained their independence. After this, the Javanese Hindu empire of Majapahit invaded Brunei and briefly ruled over Luzon Island and the Sulu Archipelago. This is recorded in the epic poem Nagarakretagama, which states that Majapahit had colonies in the Philippines at Saludong (Manila) and Solot (Sulu). Majapahit even included Butuan and Cebu's ally, Kutai. But they failed to control the Visayas islands, which were populated by Srivijayan loyalists who fought against them.

Eventually, the kingdoms of Luzon regained independence from Majapahit after the Battle of Manila (1365). Sulu also became independent again and, in revenge, attacked the Majapahit province of Poni (Brunei) before a fleet from the capital drove them out.

According to Javanese records a Javanese force expelled Sulu

marauders from Brunei during the reign of Angka Wijaya who was the last king to reign over Majapahit. The inhabitants of the Soeloe Islands (in the present Philippines) made an attack against Brunei (in order to obtain camphor), in keeping with their (piratical) nature, but they were driven off by the Javanese soldiers.

Sulu's resistance against Majapahit didn't stop there. Sulu also invaded North and East Kalimantan in Borneo, which were former Majapahit territories. The rise of Islam later led to the slow decline of Majapahit, as its provinces became independent sultanates. With the spread of Islam, the remaining Hindu Majapahit people eventually fled to Bali Island.

The Sultanate of Sulu

In 1380, Karim ul' Makdum and Shari'ful Hashem Syed Abu Bakr, an Arab trader from Johore, Malaysia, arrived in Sulu. They established the Sultanate of Sulu by converting the previous Hindu king, Rajah Baguinda, to Islam and marrying his daughter. This sultanate became very wealthy from diving for fine pearls. Before Islam, the Rajahnate of Sulu was founded by Visayan-speaking Hindu migrants from the Rajahnate of Butuan. Tausug, the language of Sulu, is classified as a Southern Visayan language. Between the 10th and 13th centuries, the Champa civilization in Central Vietnam and the port-kingdom of Sulu traded with each other. Cham merchants settled in Sulu, known as Orang Dampuan. The Orang Dampuan were later attacked by envious native Sulu Buranuns. Peaceful trade was restored, and the Orang Dampuans became ancestors of the local Yakan people. Sulu was briefly ruled by the Hindu Majapahit empire, but later, Sulu and Manila rebelled and attacked Brunei, a Majapahit province. With the arrival of Islam in the 15th century, the people of Sulu allied with their new Arab-descended Sultans and other Muslim groups (Moros), rather than their Hindu, Visayan-speaking relatives. This led to royal marriages between the newly Islamized Rajahnate of Manila and the Sultanates of Brunei, Sulu, and Malacca.

The Sultanate of Maguindanao

The Sultanate of Maguindanao became important at the end of the 15th century. Shariff Mohammed Kabungsuwan from Johor, Malaysia, introduced Islam to Mindanao. He married Paramisuli, an Iranun princess from Mindanao, and established the Sultanate of Maguindanao.

It ruled most parts of Mindanao and continued until the 19th century. The Sultanate also traded and maintained good relations with the Chinese, Dutch, and British.

The Sultanate of Lanao

The Sultanates of Lanao in Mindanao were founded in the 16th century, influenced by Shariff Kabungsuan, who became the first Sultan of Maguindanao in 1520. Muslim missionaries and traders from the Middle East, India, and Malay regions spread Islam to Sulu and Maguindanao.

Unlike Sulu and Maguindanao, the Sultanate system in Lanao was unique because it was decentralized. The area was divided into Four Principalities of Lanao, made up of several royal houses with specific territories. This decentralized power structure was adopted by the founders and continues today, emphasizing unity, patronage, and brotherhood among the ruling clans. By the 16th century, Islam had spread to other parts of the Visayas and Luzon.

The Bruneian Empire and Islam's Spread

After Brunei separated from the Majapahit Empire, they invited the Arab Emir from Mecca, Sharif Ali, and became an independent Sultanate. During the reign of Sultan Bolkiah (1485 to 1521), the newly Islamized Bruneian Empire decided to break Tondo's control over China trade. They attacked Tondo, defeated Rajah Gambang, and established the State of Selurong (Kingdom of Maynila) as a Bruneian satellite state. They placed Bolkiah's descendants on the throne of Maynila. A new dynasty under the Islamized Rajah Salalila was also created to challenge the House of Lakandula in Tondo. Sultan Bolkiah also married Laila Mecana, the daughter of Sulu Sultan Amir Ul-Ombra, to expand Brunei's influence in Luzon and Mindanao. Furthermore, Islam was strengthened by traders and preachers from Malaysia and Indonesia arriving in the Philippines. Brunei was so powerful that it had already conquered their Hindu Bornean neighbor, Kutai. Brunei also conquered the northern and southern parts of the Philippines but failed to conquer the Visayas islands, even though Sultan Bolkiah himself was half-Visayan.

The Lucoes: Filipino Seafarers and Warriors

At the same time Islam spread, the "Lucoes" or "Luzones" (people of Luzon) became very important. They set up communities across Southeast Asia and maintained ties with South and East Asia. They participated in trade, navigation, and military campaigns. Lucoes warriors helped the Burmese king invade Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, other Lucoes fought alongside the Siamese king to defend their capital, Ayutthaya, against the same Burmese army. They were also found in Japan, Brunei, Malacca, East Timor, and Sri Lanka, working as traders and mercenaries. One famous Luções was Regimo de Raja, a wealthy spice merchant and a high-ranking official (Temenggung) in Portuguese Malacca. He also led an international fleet that traded and protected commerce between the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea, and the medieval maritime kingdoms of the Philippines.

Pinto noted that many Luzones were in the Islamic fleets that fought the Portuguese in the Philippines in the 16th century. The Sultan of Aceh and an Ottoman commander assigned Luzones to defend Aceh. Pinto also said one Luções was named leader of the Malays remaining in the Moluccas Islands after the Portuguese conquest in 1511. Pigafetta noted that a Luções commanded the Brunei fleet in 1521.

However, Luzones also fought against Muslims. Pinto said they were among the native Filipinos who fought Muslims in 1538.

The Luzones were also pioneering seafarers. The Portuguese benefited directly from their involvement. Many Luzones chose Malacca as their base because it was strategically important. When the Portuguese took Malacca in 1512 AD, the Luzones living there held important government positions in the former sultanate. They were also large-scale exporters and ship owners, regularly sending ships to China, Brunei, Sumatra, Siam, and Sunda. One Luções official sent 175 tons of pepper to China annually. His ships were part of the first Portuguese fleet to officially visit the Chinese empire in 1517 AD.

In mainland Southeast Asia, Luzones helped the Burmese king invade Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, Luzones fought alongside the Siamese king to defend Ayutthaya. Lucoes military and trade activities reached as far as Sri Lanka, where pottery made in Luzon was found in burials.

The Portuguese soon relied on Luzones officials to manage Malacca and on Luzones warriors, ships, and pilots for their military and trade ventures in East Asia. It was through the Luzones, who regularly sent ships to China, that the Portuguese discovered the ports of Canton in 1514 AD. And it was on Luzones ships that the Portuguese sent their first diplomatic mission to China in 1517 AD. The Portuguese also thanked the Luzones for guiding their ships to Japan in 1543 AD. The Luzones impressed the Portuguese soldier Joao de Barros, who called them "the most warlike and valiant of these parts." Filipinos from Luzon (Lucoes) were not the only Filipinos abroad. Historian William Henry Scott noted that Mottama in Burma (Myanmar) had many merchants from Mindanao.

Rise and Fall of the Dapitan Kedatuan

Around 1563 AD, near the end of the precolonial era, the Kedatuan of Dapitan in Bohol became important. A Spanish missionary called it the "Venice of the Visayas" because it was a wealthy, floating city-state made of wood. However, this kingdom was attacked and destroyed by soldiers from the Sultanate of Ternate, a Muslim state from the Moluccas. The survivors, led by their datu, Pagbuaya, moved to northern Mindanao and established a new Dapitan there.

They then fought against the Sultanate of Lanao and settled in the lands they conquered. Later, to get revenge against the Muslims and Portuguese allied with the Ternateans, they helped the Spanish conquer Muslim Manila and capture Portuguese Ternate.

Rivalries Among Kingdoms

During this period, there was also a conflict between the Kingdom of Tondo and the Bruneian-controlled Islamic Rajahnate of Maynila. The ruler of Maynila, Rajah Matanda, asked his relatives in the Sultanate of Brunei for military help against Tondo. The Hindu Rajahnates of Butuan and Cebu also faced slave raids and fought wars against the Sultanate of Maguindanao. At the same time, Datu Lapulapu of Mactan rebelled against Rajah Humabon of Cebu. The population was small due to constant warfare and natural disasters like typhoons and earthquakes (as the Philippines is on the Pacific Ring of Fire). The many small states fighting over limited territory made it easy for the Spanish to conquer the islands quickly by using a "divide and conquer" strategy.

Spanish Rule (1565–1898): A New Era

Early Spanish Expeditions and Conquests

A Spanish expedition led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan saw Samar Island and anchored off Suluan Island on March 16, 1521. They landed the next day on Homonhon Island. Magellan claimed the islands for Spain and named them Islas de San Lázaro. He made friends with some local leaders, especially Rajah Humabon, and converted some to Roman Catholicism. In the Philippines, they explored many islands, including Mactan. However, Magellan was killed in the Battle of Mactan against the local datu, Lapulapu.

Over the next decades, other Spanish expeditions were sent. Ruy López de Villalobos led an expedition that visited Leyte and Samar in 1543 and named them Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip of Asturias, who later became King Philip II of Spain. This name was later used for the entire group of islands.

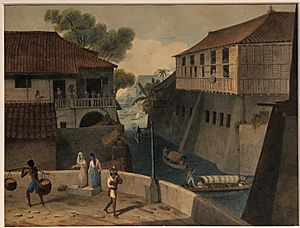

European colonization truly began when Spanish explorer Miguel López de Legazpi arrived from Mexico in 1565 and formed the first European settlements in Cebu. Starting with just five ships and five hundred men, and later reinforced, he pushed back the Portuguese and laid the groundwork for colonizing the islands. In 1571, the Spanish, with their Latin-American recruits and Filipino (Visayan) allies, led by skilled commanders like Juan de Salcedo, attacked Maynila, a state under the Brunei Sultanate. They freed and included the kingdom of Tondo and made Manila the capital of the Spanish East Indies. Early in Spanish rule, the Spanish Augustinian Friar, Gaspar de San Agustín, described Iloilo and Panay as some of the most populated and fertile islands in the Philippines. He also mentioned Halaur in Iloilo as a thriving trading post and home to important nobles.

Legazpi built a fort in Maynila and offered friendship to Lakan Dula, the Lakan of Tondo, who accepted. However, Maynila's former ruler, Rajah Sulayman, who was loyal to the Sultan of Brunei, refused to surrender to Legazpi. He failed to get support from Lakan Dula or from the Pampangan and Pangasinan settlements to the north. When Tarik Sulayman and his Kapampangan and Tagalog Muslim warriors attacked the Spanish in the Battle of Bangkusay, he was defeated and killed. The Spanish also destroyed the walled Kapampangan city-state of Cainta.

In 1578, the Castilian War broke out between the Christian Spanish and Muslim Bruneians over control of the Philippines. On one side, the newly Christianized non-Muslim Visayans from Madja-as, Cebu, and Butuan, along with the remaining Dapitan people, who had previously fought against the Sultanate of Sulu, Maguindanao, and Maynila, joined the Spanish. They fought against the Bruneian Empire and its allies: Maynila (a Bruneian puppet-state), Sulu (which had family ties with Brunei), and Maguindanao (an ally of Sulu). The Spanish and their Visayan allies attacked Brunei and captured its capital, Kota Batu. This was partly due to help from two Bruneian noblemen, Pengiran Seri Lela and Pengiran Seri Ratna. The Spanish agreed that if they won, Pengiran Seri Lela would become Sultan. In March 1578, the Spanish fleet, led by De Sande, began their journey to Brunei. The expedition included 400 Spaniards and Mexicans, 1,500 Filipino natives, and 300 Borneans. The Spanish successfully invaded the capital on April 16, 1578. Sultan Saiful Rijal and Paduka Seri Begawan Sultan Abdul Kahar were forced to flee. The Spanish suffered heavy losses from a cholera or dysentery outbreak and decided to leave Brunei on June 26, 1578, after only 72 days. Before leaving, they burned the mosque.

Pengiran Seri Lela died in August–September 1578, likely from the same illness. His daughter, a Bruneian princess, left with the Spanish and married a Christian Tagalog named Agustín de Legazpi of Tondo, having children in the Philippines.

At the same time, northern Luzon became a center for the "Bahan Trade," which involved Japanese pirates (wakō) raiding the China Seas. Some of these raiders moved to the Philippines and set up settlements in Luzon. The Philippines was a good place to launch raids on Chinese provinces and for shipping with Indochina and the Ryūkyū Islands. The Spanish fought these Japanese pirates, including warlord Tayfusa, whom they expelled after he tried to set up a city-state of Japanese pirates in Northern Luzon. The Spanish defeated them in the 1582 Cagayan battles. Because of a Chinese ban on trade with Japan in 1549 due to pirate raids, Manila became the only place where Japanese and Chinese could openly trade, often exchanging Japanese silver for Chinese silk.

In 1587, Magat Salamat, a son of Lakan Dula, along with other lords, were executed after the Tondo Conspiracy of 1587–1588 failed. This plot aimed to restore the old aristocracy with help from a Japanese Christian captain and the Sultan of Brunei. Its failure led to the hanging of Agustín de Legaspi and the execution of Magat Salamat. Some conspirators were exiled.

Spanish power grew stronger after Miguel López de Legazpi fully took control of Madja-as, defeated Rajah Tupas of Cebu, and Juan de Salcedo conquered provinces like Zambales, La Union, Ilocos, and Cagayan. He also attacked the Chinese warlord Limahong's pirate kingdom in Pangasinan.

The Spanish also invaded Northern Taiwan and Ternate in Indonesia, using Filipino warriors, before being driven out by the Dutch. The Sultanate of Ternate became independent again and later led a group of sultanates against Spain. Taiwan became a stronghold for the Ming-loyalist pirate state of Tungning. The Spanish and the Muslim groups (Moros) of Maguindanao, Lanao, and Sulu fought many wars for hundreds of years in the Spanish-Moro conflict. They were supported by the Sultanate of Ternate and the Sultanate of Brunei. Spain only succeeded in defeating the Sulu Sultanate and gaining control of Mindanao in the 19th century.

The Spanish saw their war with Muslims in Southeast Asia as a continuation of the Reconquista, a centuries-long campaign to retake Christian lands in Spain from Muslim invaders. Spanish expeditions to the Philippines were part of a larger global conflict between the Ottoman Caliphate and the Habsburgs.

Spanish forts were also set up in Taiwan and the Maluku islands. These were later abandoned, and Spanish soldiers and newly Christianized natives from the Moluccas returned to the Philippines. This was to gather forces against a threatened invasion by Koxinga, a Ming-loyalist ruler of Tungning. However, the invasion was canceled. Meanwhile, settlers were sent to Palau and the Marianas islands.

In 1593, a diplomatic group from the King of Cambodia, carrying an elephant as a gift, arrived in Manila. The King of Cambodia, who had seen the military activities of precolonial Luzones mercenaries in Burma and Siam, now asked the new rulers of Luzon, the Spanish, for help in a war to retake his kingdom from a Siamese invasion. This led to the ill-fated Spanish expedition to Cambodia, which, though a failure, set the stage for Cambodia's future restoration from Thai rule under French Cochinchina, which used Spanish allies.

Becoming Part of the Mexico-Based Viceroyalty of New Spain

The establishment of Manila on February 6, 1579, by joining the lands of Sulayman III of Namayan, Rajah Ache Matanda of Maynila (who was loyal to the Sultan of Brunei), and Lakan Dula of Tondo (who paid tribute to Ming Dynasty China), led to Manila becoming the capital. Through a Papal order, all Spanish colonies in Asia became part of the Archdiocese of Mexico. Besides Manila, the capital, Spanish and Latin American populations first gathered in the five new Spanish Royal Cities of Cebu, Arevalo, Nueva Segovia, Nueva Caceres, and Vigan. They were also spread across military outposts (Presidios) in Cavite, Calamianes, Caraga, and Zamboanga. For most of the Spanish colonial period, the Philippines was part of the Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain. Of the Spaniards and Latin Americans sent to the Philippines, almost half were reported as Spaniards, and about a third as mestizos (mixed race).

Spanish Settlements in the 16th and 17th Centuries

A 1591 report, just twenty years after Luzon's conquest, shows great progress in colonization and the spread of Christianity. A cathedral was built in Manila with a bishop's palace, monasteries for Augustinians, Dominicans, and Franciscans, and a Jesuit house. The king maintained a hospital for Spanish settlers, and another hospital for natives was run by Franciscans. To defend the settlements, the Spanish built military forts called "Presidios" across the islands. These forts were staffed by Spanish officers and guarded by Latin Americans and Filipinos, protecting against foreign nations like the Portuguese, British, Dutch, and Chinese pirates, as well as raiding Muslims.

The Manila garrison had about four hundred Spanish soldiers, and Intramuros and its surroundings were first settled by 1200 Spanish families. In Cebu City, the settlement received 2,100 soldier-settlers from New Spain. South of Manila, Mexicans were present in Ermita and Cavite as guards. Additionally, men from Peru were sent to settle Zamboanga City in Mindanao to fight Muslim pirates. These Peruvian soldiers were led by Don Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera, governor of Panama. There were also communities of Spanish-Mestizos in Iloilo, Negros, and Vigan.

Interactions between native Filipinos and immigrant Spaniards, Latin Americans, and their mixed-race descendants led to a new language, Chavacano, a mix of Mexican Spanish. In Tondo, Franciscan and Dominican friars ran convents that offered Christian education to Chinese converts. The same report shows that in and around Manila, 9,410 tributes were collected, meaning about 30,640 people were taught by thirteen missionaries. In Pampanga, the population was estimated at 74,700 with 28 missionaries. In Pangasinan, 2,400 people with eight missionaries. In Cagayan and the Babuyanes islands, 96,000 people but no missionaries. In La Laguna, 48,400 people with 27 missionaries. In Bicol and Camarines Catanduanes islands, 86,640 people with fifteen missionaries. Based on these counts, the total founding population of Spanish-Philippines was 667,612 people. This included 20,000 Chinese traders, 15,600 Latino soldier-colonists from Peru and Mexico (in the 1600s), and another 35,000 Mexican immigrants in the 1700s. There were also 3,000 Japanese residents and 600 pure Spaniards from Europe. A large but unknown number of Indian Filipinos were also present, as most slaves imported were from Bengal or Southern India. The rest were Malays and Negritos. They were cared for by 140 missionaries. During the Spanish evacuation of Ternate, Indonesia, 200 families of mixed Mexican-Filipino-Spanish and Moluccan-Portuguese descent were moved to Ternate, Cavite, and Ermita, Manila.

The islands were divided and sparsely populated due to constant wars between kingdoms and natural disasters (typhoons and earthquakes). This made Spanish invasion easy. The Spanish then brought political unity to most of the Philippines by conquering the various small sea-based states. However, they could not fully control parts of the Muslim sultanates in Mindanao and the highland areas where animist Ifugao people lived in Northern Luzon. The Spanish introduced elements of Western civilization, like a code of law, Western printing, and the Gregorian calendar. They also brought new foods like maize, pineapple, and chocolate from Latin America.

Education played a big role in changing the islands. The oldest universities, colleges, vocational schools, and the first modern public education system in Asia were all created during Spanish colonial rule. By the time the United States took over, Filipinos were among the most educated people in Asia. The Jesuits founded the Colegio de Manila in 1590, which became the Universidad de San Ignacio. They also founded the Colegio de San Ildefonso in 1595. After the Jesuits were expelled in 1768, other groups managed their schools. On April 28, 1611, the University of Santo Tomas was founded in Manila. The Jesuits also founded the Colegio de San José (1601) and took over the Escuela Municipal, later called the Ateneo de Manila University (1859). All these schools offered courses in religious topics, science (physics, chemistry, natural history, mathematics), law, medicine, and pharmacy.

Outside of universities, missionaries did more than just religious teaching. They also worked to improve the islands socially and economically. They taught natives to appreciate music and learn Spanish. They introduced better rice farming methods, brought maize and cocoa from America, and developed farming of indigo, coffee, and sugar cane. Tobacco was the only commercial plant introduced by a government agency.

Church and state were closely linked in Spanish policy, with the state responsible for religious institutions. One of Spain's goals was to convert the local population to Roman Catholicism. This was easier because other organized religions, except for Islam, were not very strong. The church's ceremonies were appealing, and local customs were included in religious events. This led to a new Roman Catholic majority. However, Muslims in western Mindanao and the tribal, animistic people of Luzon (like the Ifugaos and Mangyans) remained separate.

At lower levels of government, the Spanish used traditional village organization by working with local leaders. This system of indirect rule helped create a native upper class, called the principalía, who had local wealth, high status, and privileges. This continued a system where a few powerful families controlled local areas. One major change under Spanish rule was that the native idea of communal land use was replaced with private ownership, and titles were given to members of the principalía.

Around 1608, William Adams, an English navigator, contacted the interim governor of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco, on behalf of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who wanted to trade directly with New Spain. Friendly letters were exchanged, starting official relations between Japan and New Spain. From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from Mexico. After Mexico's independence in 1821, the Philippines was ruled directly by Spain until 1898.

The Manila galleons, built in Bicol and Cavite, were large ships that traveled between Manila and Acapulco, Mexico, once or twice a year from the 16th to 19th centuries. They brought goods, settlers, and military reinforcements from Latin America to the Philippines. On their return, they brought Asian products and immigrants to the Americas. Legally, they could only trade between Mexico and the Philippines, but illegal trade and migration happened secretly due to high demand for Asian products in Latin America.

The Spanish military fought off various native revolts and external challenges, especially from the British, Dutch, Portuguese, and Chinese pirates. Roman Catholic missionaries converted most lowland inhabitants to Christianity and founded schools, universities, and hospitals. In 1863, a Spanish law introduced public schooling in Spanish.

In 1646, a series of five naval battles known as the Battles of La Naval de Manila were fought between Spain and the Dutch Republic. Although Spanish forces had only two Manila galleons and a galley with mostly Filipino volunteers, against eighteen Dutch ships, the Spanish-Filipino forces severely defeated the Dutch, forcing them to abandon their plans to invade the Philippines.

In 1687, Isaac Newton mentioned Leuconia, the ancient name for the Philippines, in his famous book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

Spanish Rule in the 18th Century

Colonial income mainly came from trade: The Manila Galleons sailed from Manila to Acapulco, Mexico, carrying silver and coins exchanged for Asian and Pacific products. A total of 110 Manila galleons sailed during the 250 years of this trade (1565 to 1815). There was no direct trade with Spain until 1766.

The Philippines was never a profitable colony for Spain. The long war against the Dutch in the 17th century, along with constant conflict with Muslims in the South and Japanese piracy from the North, nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury. Also, the constant wars caused many deaths and desertions among the mixed-race and native soldiers from Mexico and Peru stationed in the Philippines. The high death and desertion rates also applied to native Filipino warriors forced to fight. The repeated wars, lack of pay, and near starvation were so severe that almost half of the soldiers from Latin America either died or fled to the countryside to live among rebellious natives or escaped enslaved Indians. This made it harder to govern the Philippines. The Royal Fiscal of Manila suggested abandoning the colony to King Charles III, but religious orders opposed this, seeing the Philippines as a base to convert the Far East.

The Philippines survived on an annual payment from the Spanish Crown, often from taxes and profits from the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico). Manila's 200-year-old fortifications had not been much improved. This allowed the British to briefly occupy Manila between 1762 and 1764.

British Occupation (1762–1764)

Britain declared war against Spain on January 4, 1762. On September 24, 1762, British Army soldiers and British East India Company soldiers, supported by the Royal Navy, sailed into Manila Bay from Madras, India. Manila was attacked and fell to the British on October 4, 1762.

Outside Manila, the Spanish leader Simón de Anda y Salazar organized a militia of 10,000 men, mostly from Pampanga, to resist British attempts to expand their control. Anda y Salazar set up his headquarters first in Bulacan, then in Bacolor. After several small battles and failed attempts to support Filipino uprisings, the British admitted that the Spanish controlled the country. The British occupation of Manila ended in April 1764, as agreed in the peace talks for the Seven Years' War in Europe. The Spanish then punished the Binondo Chinese community for helping the British. An unknown number of Indian soldiers (sepoys) who came with the British deserted and settled in nearby Cainta, Rizal, which explains the unique Indian features of generations of Cainta residents.

Spanish Rule in the Late 18th Century

In 1766, direct communication was established with Spain, and trade with Europe began through a national ship based in Spain. In 1774, colonial officers reported that discharged soldiers and deserters from the British occupation were training native Filipinos in using weapons that had spread during the war. Expeditions from Spain were managed by the Real Compañía de Filipinas from 1785. This company had a monopoly on trade between Spain and the islands until 1834, when it was closed due to poor management. Around this time, Governor-General Anda complained that Latin American and Spanish soldiers sent to the Philippines had spread "all over the islands, even the most distant, looking for subsistence."

In 1781, Governor-General José Basco y Vargas established the Economic Society of the Friends of the Country. The Philippines was governed from the Viceroyalty of New Spain until Mexico's independence in 1821. From that year until 1898, the Philippines was ruled directly by Spain.

Spanish Rule in the 19th Century

The Philippines was considered an overseas region of Spain, not just a colony, in the first Spanish constitution in Cadiz in 1812. The Spanish Constitution of 1870 even planned for the "Archipelago Filipino" to have its own semi-independent local rule.

In the 19th century, Spain invested heavily in education and infrastructure. The Education Decree of December 20, 1863, by Queen Isabella II of Spain, created a free public school system using Spanish as the language of instruction. This led to more educated Filipinos. Also, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 shortened travel time to Spain, helping the rise of the ilustrados, an educated class of Spanish-Filipinos who studied in Spanish and European universities.

Many infrastructure projects were built in the 19th century, improving the Philippine economy and living standards beyond most Asian neighbors and even some European countries. These included a railway system for Luzon, a tramcar network for Manila, and Asia's first steel suspension bridge, Puente Claveria (later Puente Colgante).

On August 1, 1851, the Banco Español-Filipino de Isabel II was established to support the fast-growing economy, which had boomed since the 1800s due to better use of agricultural resources. Increased production of textile fibers like abacá, coconut oil, and indigo led to more money, prompting the bank's creation. This bank was also allowed to print a specific currency for the Philippines (the Philippine peso) for the first time.

Spanish Manila in the 19th century was seen as a good example of colonial governance that put the interests of the native inhabitants first. As John Crawfurd wrote, in all of Asia, "the Philippines alone did improve in civilization, wealth, and populousness under the colonial rule" of a foreign power. John Bowring, Governor General of British Hong Kong, wrote after visiting Manila:

Credit is certainly due to Spain for having bettered the condition of a people who, though comparatively highly civilized, yet being continually distracted by petty wars, had sunk into a disordered and uncultivated state.

The inhabitants of these beautiful Islands upon the whole, may well be considered to have lived as comfortably during the last hundred years, protected from all external enemies and governed by mild laws vis-a-vis those from any other tropical country under native or European sway, owing in some measure, to the frequently discussed peculiar (Spanish) circumstances which protect the interests of the natives.

Frederick Henry Sawyer wrote in The Inhabitants of the Philippines:

Until an inept bureaucracy was substituted for the old paternal rule, and the revenue quadrupled by increased taxation, the Filipinos were as happy a community as could be found in any colony. The population greatly multiplied; they lived in competence, if not in affluence; cultivation was extended, and the exports steadily increased. [...] Let us be just; what British, French, or Dutch colony, populated by natives can compare with the Philippines as they were until 1895?.

The first official census in the Philippines was in 1878, recording 5,567,685 people. The 1887 census counted 6,984,727, and the 1898 census counted 7,832,719 inhabitants.

Latin-American Revolutions and Direct Spanish Rule

Filipinos living abroad were involved in several anti-colonial movements in the Americas. Filipinos, called Manilamen, were active in navies and armies worldwide. For example, Filipinos were part of Hypolite Bouchard's crew during the Argentine war of independence. It's thought these Filipinos were recruited in San Blas, Mexico, where many Filipinos had settled during the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade. Argentinian-Philippine relations go back even further, as the Philippines received immigrants from South America, like the soldier Juan Fermín de San Martín, brother of the Argentine Revolution leader Jose de San Martin. In Mexico, about 200 Filipinos joined Miguel Hidalgo's revolution against Spain, including Manila-born Ramon Fabié. General Isidoro Montes de Oca, another Filipino-Mexican, also fought in the Mexican Revolutionary war. Filipinos in Saint Malo, Louisiana, helped the United States defend New Orleans during the War of 1812.

After Mexico gained independence, there were plans among Mexicans to help Filipinos revolt against Spain. A secret Mexican government memo suggested sending agents to encourage Filipinos to rise up, promising financial and military aid. It also proposed an alliance of friendship and trade with an independent Philippines.

Filipinos abroad were also active in Asia-Pacific, especially in China and Indochina. During the Taiping rebellion in China, Frederick Townsend Ward hired foreigners, including Filipinos, for his militia. Caleb Carr noted that Filipinos in Shanghai "were handy on board ships and more than a little troublesome on land." Smith also wrote that Manilamen were "reputed to be brave and fierce fighters" and "were plentiful in Shanghai and always eager for action." In July 1860, Townsend Ward's force of 100-200 Manilamen successfully attacked Sung-Chiang Prefecture. So, while the Philippines was slowly developing revolutionary spirit under Spanish suppression, Filipinos abroad played active roles in military and naval conflicts in the Americas and Asia-Pacific. Soldiers from the Philippines were recruited by France, an ally of Spain, to protect Christian converts in Indochina and later to conquer Vietnam and Laos. They also helped establish the Protectorate of Cambodia, freeing it from Thai invasions.

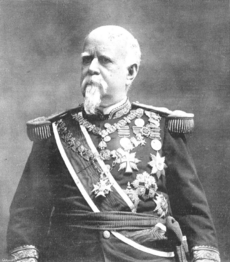

Dissatisfaction among the Criollo (Spaniards born in the Philippines) and Latino (Latin Americans) against the Peninsulares (Spaniards directly from Spain) grew. The Criollos and Latinos loved their land and people and resented the exploitative Peninsulares, who were appointed to high positions only because of their race and loyalty to Spain. This led to the uprising of Andres Novales, a Philippine-born soldier who gained fame in Spain but chose to serve in the Philippines. He was supported by local soldiers and former officers from newly independent Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina, and Costa Rica. The uprising was brutally suppressed but foreshadowed the 1872 Cavite Mutiny, which was a step towards the Philippine Revolution. However, Hispanic-Philippines reached its peak when the Philippine-born Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero became a hero for restoring the Bourbon Dynasty of Spain to the throne. He eventually became Prime Minister of the Spanish Empire. After Chilean soldiers participated in the Andres Novales uprising, Bernardo O'Higgins, the founder of Chile, planned to send a fleet to free the Philippines from Spain, but his exile prevented it.

Philippine Revolution

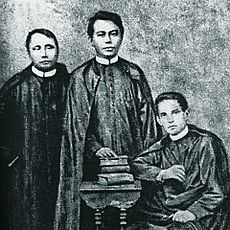

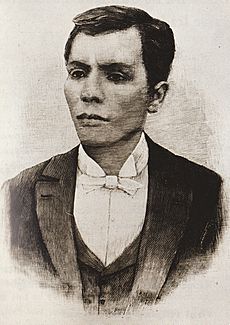

Revolutionary feelings grew in 1872 after three Filipino priests, Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, known as Gomburza, were wrongly accused of rebellion and executed. This inspired the Propaganda Movement in Spain, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, Graciano López Jaena, and Mariano Ponce. They demanded fair representation in the Spanish Cortes and later, independence. José Rizal, a famous intellectual, wrote the novels "Noli Me Tángere" and "El filibusterismo," which greatly inspired the independence movement. The Katipunan, a secret society aiming to overthrow Spanish rule, was founded by Andrés Bonifacio, who became its leader (Supremo).

In the 1860s to 1890s, in Philippine cities, especially Manila, pure European Spaniards made up about 3.3% of the population, and pure Chinese were as high as 9.9%. The Spanish-Filipino and Chinese-Filipino Mestizo populations also changed. Eventually, people in these non-native categories decreased because they were absorbed and chose to identify as pure Filipinos. During the Philippine Revolution, the term "Filipino" included anyone born in the Philippines, regardless of race. This explains the sharp drop in Chinese, Spanish, and mestizo percentages by the first American census in 1903.

The Philippine Revolution began in 1896. Rizal was wrongly linked to the revolution and executed for treason in 1896. The Katipunan in Cavite split into two groups: Magdiwang, led by Mariano Álvarez, and Magdalo, led by Baldomero Aguinaldo. Conflicts between these groups led to the Tejeros Convention in 1897, where Emilio Aguinaldo was elected president over Bonifacio. Later leadership conflicts with Bonifacio led to his execution by Aguinaldo's soldiers. Aguinaldo agreed to a truce with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato and was exiled to Hong Kong. Not all revolutionary generals followed the agreement. General Francisco Macabulos set up a Central Executive Committee as a temporary government. Armed conflicts resumed in almost every Spanish-governed province.

In 1898, as conflicts continued in the Philippines, the USS Maine exploded and sank in Havana harbor, leading to the Spanish-American War. After Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish squadron in Manila, a German squadron arrived and made maneuvers that Dewey saw as obstruction. He offered war, and the Germans backed down. The German Emperor expected an American defeat, leaving Spain weak enough for revolutionaries to capture Manila, making the Philippines ready for German taking.

The U.S. invited Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines, hoping he would rally Filipinos against the Spanish. Aguinaldo arrived on May 19, 1898. On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared Philippine independence in Kawit, Cavite. Aguinaldo proclaimed a Revolutionary Government on June 23. By the time U.S. land forces arrived, Filipinos controlled all of Luzon except the Spanish capital in Intramuros. In the Battle of Manila on August 13, 1898, the United States captured the city from the Spanish. This battle ended Filipino-American cooperation, as Filipino forces were prevented from entering Manila, which deeply angered Filipinos.

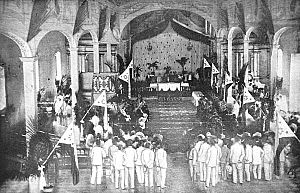

The First Philippine Republic (1899–1901)

On January 23, 1899, the First Philippine Republic was declared under Asia's first democratic constitution, with Aguinaldo as president. Under Aguinaldo, the Philippine Revolutionary Army was known for being racially tolerant and diverse, with officers from various backgrounds. Juan Cailles, an Indian and French Mestizo, served as a Major General. José Ignacio Paua, a Chinese Filipino, was a Brigadier General. Vicente Catalan, appointed Supreme Admiral of the Philippine Revolutionary Navy, was a Cuban of Criollo descent. There were even Japanese, French, and Italian soldiers in the Revolution and Republic. Some defeated Spanish and American soldiers even joined the Philippine Republic. The most famous was African-American Captain David Fagen, who joined Filipinos because he disliked American racism. Various nations, mostly Latin American, influenced the new Republic. The Sun in the Philippine flag was taken from the Sun of May of Peru, Argentina, and Uruguay, symbolizing the Incan Sun God Inti. The stars in the flag were inspired by the flags of Texas, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. The Constitution of the First Philippine Republic was also influenced by the Constitutions of Cuba, Belgium, Mexico, Brazil, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Guatemala, as well as the French Constitution of 1793.

Despite the First Philippine Republic's establishment, Spain and the United States sent commissioners to Paris to finalize the Treaty of Paris, ending the Spanish-American War. The Filipino representative, Felipe Agoncillo, was excluded because Aguinaldo's government was not recognized by other nations. Although there was strong opposition within the U.S., the United States decided to annex the Philippines. Even though the First Philippine Republic was modeled after the French and American Revolutions and Latin American Republics, the Americans and French themselves sought to suppress the revolution in the Philippines. Besides Guam and Puerto Rico, Spain was forced to give the Philippines to the U.S. for $20,000,000. U.S. President McKinley justified this by saying it was "a gift from the gods" and that Filipinos were "unfit for self-government," so the U.S. had to "educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them," even though the Spanish had already Christianized the Philippines over centuries. The First Philippine Republic resisted the U.S. occupation, leading to the Philippine-American War (1899–1913).

The estimated GDP per person for the Philippines in 1900, the year Spain left and the First Philippine Republic was active, was $1,033. This made it the second-richest place in Asia, just behind Japan ($1,135) and far ahead of China ($652) and India ($625).

American Rule (1898–1946)

Filipinos initially saw their relationship with the United States as a partnership against Spain. However, the United States later distanced itself from the Filipino rebels' goals. Emilio Aguinaldo was unhappy that the U.S. would not officially support Philippine independence. Spain gave the islands to the United States, along with Puerto Rico and Guam, after the U.S. won the Spanish-American War. The U.S. paid Spain $20 million as part of the 1898 Treaty of Paris. Relations worsened, and tensions grew as it became clear that the Americans intended to stay in the islands.

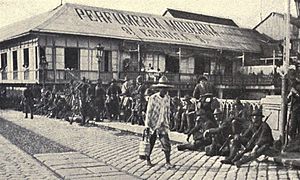

Philippine-American War

Fighting broke out on February 4, 1899, after two American soldiers killed three Filipino soldiers in San Juan, a Manila suburb. This started the Philippine-American War, which cost more money and lives than the Spanish-American War. About 126,000 American soldiers were sent, and 4,234 Americans died. Between 12,000–20,000 Philippine Republican Army soldiers died, part of a nationwide guerrilla movement of at least 80,000 to 100,000 soldiers.

The general population suffered greatly, caught between Americans and rebels. At least 200,000 Filipino civilians died indirectly from the war, mostly from a cholera epidemic at the war's end that killed between 150,000 and 200,000 people. Both sides committed terrible acts.

The poorly equipped Filipino troops were easily defeated by American troops in open battles, but they were strong opponents in guerrilla warfare. Malolos, the revolutionary capital, was captured on March 31, 1899. Aguinaldo and his government escaped, setting up a new capital in San Isidro, Nueva Ecija. On June 5, 1899, Antonio Luna, Aguinaldo's most skilled military commander, was killed by Aguinaldo's guards in an apparent assassination. With his best commander dead and his troops losing battles as American forces pushed into northern Luzon, Aguinaldo disbanded the regular army on November 13 and ordered the creation of decentralized guerrilla commands. Another key general, Gregorio del Pilar, was killed on December 2, 1899, in the Battle of Tirad Pass, a rearguard action to delay the Americans while Aguinaldo escaped through the mountains.

Aguinaldo was captured in Palanan, Isabela, on March 23, 1901, and brought to Manila. Convinced that further resistance was useless, he swore loyalty to the United States and called on his countrymen to lay down their arms, officially ending the war. However, scattered rebel resistance continued in various parts of the Philippines, especially in the Muslim south, until 1913.

In 1900, President McKinley sent the Taft Commission to the Philippines to create laws and reshape the political system. On July 1, 1901, William Howard Taft, the commission's head, became Civil Governor with limited executive powers. The military governor's authority continued in areas where the rebellion persisted. The Taft Commission passed laws to set up the new government's basics, including a judicial system, civil service, and local government. A Philippine Constabulary was formed to deal with remaining rebels and gradually take over duties from the United States Army.

The Tagalog, Negros, and Zamboanga Republics

Brigadier General James F. Smith arrived in Bacolod on March 4, 1899, as the Military Governor of Negros, after an invitation from Aniceto Lacson, president of the independent Cantonal Republic of Negros. The Negros Republic became a pro-American protectorate of the United States. Another rebel republic was briefly formed during American rule: the Tagalog Republic in Luzon, under Macario Sakay. In Mindanao, the Chavacano-speaking Republic of Zamboanga was proclaimed. This government was formed by Vicente Álvarez with support from Jamalul Kiram II, the Sultan of Sulu. It included Latin American soldiers who had rebelled against the Spanish colonial government.

Insular Government (1901–1935)

The Philippine Organic Act (1902) was the basic law for the Insular Government, named because civil administration was under the U.S. Bureau of Insular Affairs. This government saw its goal as preparing the Philippines for eventual independence. On July 4, 1902, the military governor's office was ended, and full executive power went from Adna Chaffee, the last military governor, to Taft, who became the first U.S. Governor-General of the Philippines. U.S. policies towards the Philippines changed with different administrations. In the early years, Americans were hesitant to give power to Filipinos, but an elected Philippine Assembly was created in 1907 as the lower house of a two-house legislature. The appointed Philippine Commission became the upper house.

The Philippines was a major focus for progressive reformers. A 1907 report to Secretary of War Taft summarized the American civil administration's achievements. Besides quickly building a public school system teaching in English, it boasted about modernizing achievements like:

- Steel and concrete wharves at the newly renovated Port of Manila

- Dredging the Pasig River

- Streamlining the Insular Government

- Accurate, understandable accounting

- Building a telegraph and cable communications network

- Establishing a postal savings bank

- Large-scale road and bridge building

- Fair and honest policing

- Well-funded civil engineering

- Preserving old Spanish architecture

- Large public parks

- A bidding process for railway construction

- Corporation law

- A coastal and geological survey

In 1903, American reformers passed two major land laws to turn landless farmers into farm owners. By 1905, the law clearly failed. Reformers like Taft believed landownership would make rebellious farmers loyal. The social structure in rural Philippines was very traditional and unequal. Big changes in land ownership were a major challenge to local elites, who would not accept it, nor would their peasant clients. American reformers blamed peasant resistance for the law's failure and argued that large plantations and sharecropping were the best path for the Philippines' development.

Elite Filipino women played a big role in the reform movement, especially on health issues. They focused on urgent needs like infant care, maternal and child health, distributing pure milk, and teaching new mothers about children's health. The most important organizations were La Protección de la Infancia and the National Federation of Women's Clubs.

When Democrat Woodrow Wilson became U.S. president in 1913, new policies aimed to gradually lead to Philippine independence. In 1902, U.S. law established Filipinos as citizens of the Philippine Islands; unlike Hawaii and Puerto Rico, they did not become U.S. citizens. The Jones Law of 1916 became the new basic law, promising eventual independence. It allowed for the election of both houses of the legislature.

Economically and socially, the Philippines made good progress during this time. Foreign trade was 62 million pesos in 1895, with 13% of it with the United States. By 1920, it grew to 601 million pesos, with 66% of it with the United States. A healthcare system was set up, which by 1930, reduced the death rate from all causes, including tropical diseases, to a level similar to that of the United States. Practices like slavery, piracy, and headhunting were suppressed but not completely eliminated. A new education system was established with English as the language of instruction, which eventually became a common language in the islands. The 1920s saw periods of cooperation and conflict with American governors-general, depending on how much power they wanted to use over the Philippine legislature. Members of the elected legislature pushed for immediate and full independence from the United States. Several independence missions were sent to Washington, D.C. A civil service was formed and gradually taken over by Filipinos, who largely controlled it by 1918.

Philippine politics during the American period was dominated by the Nacionalista Party, founded in 1907. Although the party called for "immediate independence," their policy towards the Americans was very cooperative. Within the political establishment, Manuel L. Quezon led the call for independence, serving as Senate president from 1916 to 1935.

World War I gave the Philippines a chance to help the U.S. war effort. This included offering to provide a division of troops and funding for two warships. A local national guard was created, and many Filipinos volunteered for service in the U.S. Navy and army.

Daniel Burnham created an architectural plan for Manila that would have turned it into a modern city.

Frank Murphy was the last Governor-General of the Philippines (1933–35) and the first U.S. High Commissioner of the Philippines (1935–36). This change was more than symbolic; it showed the transition towards independence.

Commonwealth Period

The Great Depression in the early 1930s sped up the Philippines' path to independence. In the United States, the sugar industry and labor unions wanted to loosen ties with the Philippines because they couldn't compete with cheap Philippine sugar and other goods that entered the U.S. market freely. So, they pushed for Philippine independence to keep out its cheap products and labor.

In 1933, the United States Congress passed the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act as a Philippine Independence Act, overriding President Herbert Hoover's veto. Although the bill was drafted with help from a Philippine commission, Philippine Senate President Manuel L. Quezon opposed it, partly because it allowed the United States to control naval bases. Under his influence, the Philippine legislature rejected the bill. The next year, a revised act called the Tydings–McDuffie Act was finally passed. This act provided for the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, with full independence after a ten-year period. The Commonwealth would have its own constitution and be self-governing, though foreign policy would be the U.S.'s responsibility, and some laws needed U.S. president approval. The Act stated that independence would be on July 4, ten years after the Commonwealth's establishment.

A Constitutional Convention met in Manila on July 30, 1934. On February 8, 1935, the 1935 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines was approved. President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved it on March 23, 1935, and it was ratified by popular vote on May 14, 1935.

On September 17, 1935, presidential elections were held. Candidates included former president Emilio Aguinaldo and Gregorio Aglipay. Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña of the Nacionalista Party won as president and vice-president.

The Commonwealth Government was inaugurated on November 15, 1935, in Manila, attended by about 300,000 people. Under the Tydings–McDuffie Act, full independence for the Philippines was set for July 4, 1946, a timeline that was followed after almost eleven very eventful years.

The new government started ambitious nation-building policies to prepare for economic and political independence. These included national defense (like the National Defense Act of 1935, which organized conscription), more control over the economy, improving democratic institutions, education reforms, better transport, promoting local businesses, industrialization, and colonizing Mindanao.

However, uncertainties, especially in the diplomatic and military situation in Southeast Asia, the level of U.S. commitment to the future Philippines, and the economy due to the Great Depression, were major problems. The situation was made more complex by farmer unrest and power struggles between Osmeña and Quezon.

It's hard to properly evaluate the policies' success or failure due to the Japanese invasion and occupation during World War II.

World War II and Japanese Occupation