Wang Jingwei facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

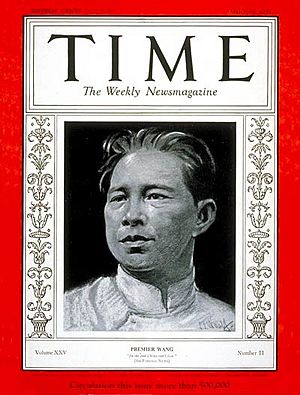

Wang Jingwei

|

|

|---|---|

|

汪精衞

|

|

|

|

| 1st President of the Republic of China President of Executive Yuan (Reorganized National Government) |

|

| In office 20 March 1940 – 10 November 1944 |

|

| Vice President | Zhou Fohai |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Chen Gongbo |

| Premier of the Republic of China | |

| In office 28 January 1932 – 1 December 1935 |

|

| President | Lin Sen |

| Preceded by | Sun Fo |

| Succeeded by | Chiang Kai-shek |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 May 1883 Sanshui, Canton, Qing Empire |

| Died | 10 November 1944 (aged 61) Nagoya, Empire of Japan |

| Political party | Kuomintang Kuomintang-Nanjing |

| Spouse | Chen Bijun |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Peacebuilding National Army |

| Years of service | 1940–1944 |

| Rank | Generalissimo (特級上將) |

| Battles/wars | Second Sino-Japanese War |

| Wang Jingwei | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 汪精衞 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汪精卫 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (pen name) | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Wang Zhaoming | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 汪兆銘 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汪兆铭 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (birth name) | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Wang Zhaoming, known by his pen name Wang Jingwei (born May 4, 1883 – died November 10, 1944), was an important Chinese politician. He was first a member of the left-leaning group within the Kuomintang (KMT), a major political party in China. He even led a government in Wuhan that was against the right-leaning KMT government in Nanjing.

Later, Wang became very much against communism. This happened after his attempts to work with the Chinese Communist Party did not succeed. His political views changed a lot, especially after he started working with the Japanese.

Wang was a close friend and helper of Sun Yat-sen, who founded the Republic of China. They worked together for the last twenty years of Sun's life. After Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, Wang and Chiang Kai-shek fought for control of the Kuomintang. Wang lost this power struggle.

He stayed in the Kuomintang but often disagreed with Chiang Kai-shek. This continued until the Second Sino-Japanese War began in 1937. During the war, the Japanese Empire invited Wang to form a government that would work with them in Nanjing. Wang became the leader of this government, which many called a "puppet government" because it was controlled by Japan. He led it until he died, just before World War II ended.

Today, historians still debate Wang's actions. He is seen as a key figure in the 1911 Revolution, which overthrew the old Chinese empire. However, his cooperation with Japan is very controversial. Many people in China consider him a traitor for his role in the war against Japan. His name has even become a symbol for treason.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Wang was born in Sanshui, Guangdong, but his family came from Zhejiang. In 1903, he went to Japan to study, with support from the Qing Dynasty government. While there, he joined the Tongmenghui in 1905. As a young man, Wang felt that the Qing dynasty was holding China back. He believed it made China too weak to stop powerful Western countries from taking advantage of it.

In Japan, Wang became a trusted friend of Sun Yat-sen. He later became one of the most important members of the early Kuomintang. He was also influenced by ideas of anarchism and wrote articles for journals.

Early Political Career

In the years before the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, Wang actively opposed the Qing government. He became well-known as a great public speaker and a strong supporter of Chinese nationalism. He was put in jail for planning to assassinate the regent, Zaifeng, Prince Chun. Wang admitted his guilt during his trial.

He stayed in jail from 1910 until the Wuchang Uprising in 1911. After his release, he was seen as a national hero.

Working with Sun Yat-sen

During and after the Xinhai Revolution, Wang focused on fighting against Western powers trying to control China. In the early 1920s, he held several positions in Sun Yat-sen's government in Guangzhou. He was the only close friend of Sun who traveled with him outside KMT-controlled areas before Sun's death.

Many believe Wang wrote Sun's will in late 1925. After Sun's death, Wang was considered a top candidate to lead the KMT. However, he eventually lost control of the party and the army to Chiang Kai-shek. By 1926, Chiang had clearly taken charge. He sent Wang and his family to Europe for a vacation. This was important for Chiang because Wang led the KMT's left wing, which was friendly towards communists. Chiang wanted Wang away while he removed communists from the KMT.

Rivalry with Chiang Kai-shek

Leading the Wuhan Government

During the Northern Expedition, Wang was a key figure in the KMT's left-leaning group. This group wanted to continue working with the Chinese Communist Party. Even though Wang worked closely with Chinese communists in Wuhan, he did not agree with communism. He also did not trust the KMT's advisors from the Comintern (a communist organization). He believed communists could not be true Chinese patriots.

In early 1927, Wang's group declared Wuhan to be the capital of the Republic. This happened shortly before Chiang Kai-shek captured Shanghai and moved his capital to Nanjing. While leading the government from Wuhan, Wang worked closely with important communist leaders like Mao Zedong. His group also made controversial land reform policies. Wang later said that his Wuhan government failed because it adopted too many communist ideas.

Chiang Kai-shek opposed Wang's government. Chiang was busy removing communists in Shanghai and wanted to push his forces further north. The split between Wang's government in Wuhan and Chiang's government in Nanjing is known as the "Ninghan Separation."

In April 1927, Chiang Kai-shek took control of Shanghai. He then began a violent crackdown on suspected communists, known as the "Shanghai Massacre." Within weeks, Wang's government was attacked by a warlord allied with the KMT and quickly fell apart. This left Chiang as the only recognized leader of the Republic. KMT troops in areas Wang once controlled killed many suspected communists. For example, over ten thousand people were killed in Changsha in just twenty days. Fearing he would be punished for being friendly to communists, Wang publicly supported Chiang before escaping to Europe.

Political Roles in Chiang's Government

Between 1929 and 1930, Wang worked with other military leaders to form a government against Chiang. Wang tried to help this opposing government, but Chiang defeated their alliance in the Central Plains War.

In 1931, Wang joined another anti-Chiang government in Guangzhou. After Chiang defeated this group, Wang made peace with Chiang's Nanjing government. He held important positions for most of the next decade. Wang became premier when the Battle of Shanghai (1932) began. He often argued with Chiang and would resign in protest, only to be asked to return. Because of these power struggles within the KMT, Wang often had to live in exile. He traveled to Germany and even had some contact with Adolf Hitler.

Chiang wanted Wang as premier to make his government look "progressive." This was important because Chiang was fighting a civil war against the Communists. Wang also helped shield Chiang's government from public criticism for its policy of "first internal pacification, then external resistance." This meant defeating the Communists first, then fighting Japan. Even though Wang and Chiang did not like or trust each other, Chiang was willing to compromise to keep Wang as premier.

Regarding Japan, Wang and Chiang had different ideas. Wang was very pessimistic about China's ability to win a war against Japan. He was against alliances with any foreign powers if war came. Wang believed China had to defeat Japan on its own to stay independent. However, he also thought China was too weak to win against Japan, which had been modernizing since 1867. This made him want to avoid war at almost any cost and try to negotiate with Japan to keep China's independence.

Chiang, on the other hand, believed that if his modernization plans had enough time, China would win the war. If war came sooner, he was willing to ally with any foreign power to defeat Japan, even the Soviet Union. Chiang was more strongly anti-Communist than Wang, but he was also a "realist" who would ally with the Soviet Union if needed. While Wang and Chiang agreed on the "first internal pacification, then external resistance" policy in the short term, their long-term goals differed. Wang was more willing to compromise with Japan, while Chiang just wanted to buy time to prepare China for war. The KMT's effectiveness was often hurt by these leadership struggles. In December 1935, Wang left the premiership for good after being badly hurt in an assassination attempt a month earlier.

In 1936, Wang and Chiang disagreed on foreign policy. Wang, who was seen as left-wing, argued for China to sign the Anti-Comintern Pact with Germany and Japan. Chiang, seen as right-wing, wanted to improve relations with the Soviet Union. During the 1936 Xi'an Incident, when Chiang was captured by his own general, Zhang Xueliang, Wang wanted to send troops to attack Zhang. He was ready to march, but Chiang's wife and brother-in-law feared this would lead to Chiang's death and Wang taking his place. So, they stopped this action.

Wang went with the government when it moved to Chongqing during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). During this time, he formed some right-wing groups within the KMT. Wang was initially part of the group that wanted to fight the war. But after Japan successfully took over large parts of China's coast, Wang became very pessimistic about China's chances. He often said China would lose in KMT meetings. He continued to believe that Western powers were a greater danger to China, which upset his colleagues. Wang thought China needed to make a deal with Japan so that Asian countries could resist Western powers together.

Alliance with Japan

In late 1938, Wang left Chongqing and went to Hanoi, French Indochina. He stayed there for three months and announced that he supported a peace deal with the Japanese. During this time, KMT agents tried to assassinate him, and he was wounded. Wang then flew to Shanghai and began talks with Japanese officials. The Japanese invasion gave him the chance he had long wanted to create a new government separate from Chiang Kai-shek's control.

On March 30, 1940, Wang became the head of state of what was called the Wang Jingwei regime. This government was formally known as the "Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China" and was based in Nanjing. Wang served as the President of the Executive Yuan and Chairman of the National Government. In November 1940, Wang's government signed the "Sino-Japanese Treaty" with the Japanese. This document gave Japan many political, military, and economic benefits, similar to Japan's earlier Twenty-one Demands.

In June 1941, Wang gave a public radio speech from Tokyo. In it, he praised Japan and confirmed China's cooperation with them. He criticized the Kuomintang government and promised to work with Japan to fight communism and Western influence. Wang continued to manage his government's policies in line with Japan's goals. For example, in 1943, he took control of the French Concession and the International Settlement of Shanghai. This happened after Western nations agreed to end their special rights in China.

Wang's government, which worked with Japan, was based on three main ideas: Pan-Asianism (the idea that Asian countries should unite), anti-communism, and opposition to Chiang Kai-shek. Wang also kept in touch with German Nazis and Italian fascists, whom he had met while in exile.

Life Under the Wang Jingwei Regime

Life was often difficult in the parts of China controlled by Wang's government, and it got harder as the war turned against Japan around 1943. People living there often used the black market to get things they needed. The Japanese secret police, along with Chinese police working for the Japanese, censored information and tortured enemies. A Chinese secret agency, the Tewu, was also created with help from Japanese advisors. The Japanese also set up prisoner-of-war camps and training centers for pilots.

Wang's government only had power in areas occupied by the Japanese military. This meant officials loyal to Wang could do little to help Chinese people suffering under Japanese rule. Wang himself became a target for those resisting Japan. Both the KMT and the Communist Party called him a "traitor." Wang and his government were very unpopular with the Chinese people, who saw them as betraying China and their Chinese identity. Resistance and sabotage constantly weakened Wang's rule.

The local education system aimed to train people for factory and mine work, and for general manual labor. The Japanese also tried to introduce their culture and clothing to the Chinese. People complained and demanded more meaningful Chinese education. Japanese temples and cultural centers were built to spread Japanese culture and values. These activities stopped when the war ended.

Death

In March 1944, Wang went to Japan for medical treatment. He was still suffering from a wound from an assassination attempt in 1939. He died in Nagoya on November 10, 1944. This was less than a year before Japan surrendered to the Allies, so he avoided being tried for treason. Many of his senior followers who survived the war were executed.

His death was not announced in Japanese-occupied China until November 12, after events celebrating Sun Yat-sen's birthday had finished. Wang was buried in Nanjing, close to the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, in a grand tomb. Soon after Japan's defeat, Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang government moved its capital back to Nanjing. They destroyed Wang's tomb and burned his body. Today, a small pavilion marks the site, noting Wang as a traitor.

Legacy and Historical View

Because of his actions during the Pacific War, most Chinese historians after World War II, in both Taiwan and mainland China, consider Wang a traitor. His name has become a common word for "traitor" or "treason" in China, similar to how "Quisling" is used in Europe or "Benedict Arnold" in the United States.

Both the Communist and Nationalist governments strongly criticized Wang for working with the Japanese. The Communist Party highlighted his anti-communism, while the Kuomintang focused on his personal betrayal of Chiang Kai-shek. The communists also argued that his high rank in the KMT showed a dishonest, treasonous nature within the Nationalist party itself. Both sides chose to downplay his earlier close connection with Sun Yat-sen.

Despite the negative reputation, some academics still discuss whether he should be fully condemned as a traitor. They point out that Wang contributed greatly to the 1911 revolution and later helped mediate between the Communist and Nationalist parties. These scholars argue that Wang worked with the Japanese because he believed it was the only hope for his desperate countrymen.

Personal Life

Wang was married to Chen Bijun. They had six children together, and five of them lived to adulthood.

- Wang's oldest son, Wenjin, was born in France in 1913.

- His oldest daughter, Wenxing, was born in France in 1915. She worked as a teacher in Hong Kong after 1948 and moved to the US in 1984, where she died in 2015.

- Wang's second daughter, Wang Wenbin, was born in 1920.

- His third daughter, Wenxun, was born in Guangzhou in 1922 and died in 2002 in Hong Kong.

- Wang's second son, Wenti, was born in 1928. In 1946, he was given a prison sentence for being a hanjian (a term for a Chinese traitor). After serving his time, Wang Wenti settled in Hong Kong. Since the 1980s, he has been involved in many education projects with mainland China.

See also

In Spanish: Wang Jingwei para niños

In Spanish: Wang Jingwei para niños

- Huang Yiguang, and his assassination attempt on Wang Jingwei

- Vidkun Quisling

- Ye Wanyong

- Anton Mussert