Zhang Zuolin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Zhang Zuolin

|

|

|---|---|

|

張作霖

|

|

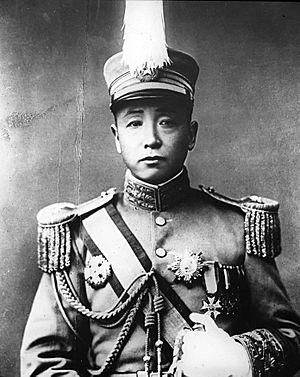

Zhang in military uniform

|

|

| Generalissimo of the Military Government of China |

|

| In office 18 June 1927 – 4 June 1928 |

|

| Premier | Pan Fu |

| Preceded by | Wellington Koo (as acting president) |

| Succeeded by | Tan Yankai (as chairman of the national government) |

| Warlord of Manchuria | |

| In office 1922 – June 4, 1928 |

|

| Succeeded by | Zhang Xueliang |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 19, 1875 Haicheng, Fengtian, Qing Empire |

| Died | June 4, 1928 (aged 53) Shenyang, Fengtian, Republic of China |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Political party | Fengtian clique |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 14, including:

|

| Awards | Order of Rank and Merit Order of the Golden Grain Order of Wen-Hu |

| Nicknames | Old Marshal Rain Marshal Mukden Tiger King of the Northeast |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1900–1928 |

| Rank | Grand Marshal of the Republic of China, generalissimo |

| Battles/wars |

|

Zhang Zuolin (March 19, 1875 – June 4, 1928) was a powerful Chinese military leader, known as a warlord. He ruled the region of Manchuria from 1916 to 1928. He led the Fengtian clique, which was one of the most important groups during China's Warlord Era. For a short time in his last year, he even became the President of the Republic of China.

Zhang was born into a poor farming family in Manchuria. At age twenty, he joined the army as a cavalry soldier. He fought in the First Sino–Japanese War (1894–1895). After the war, he went back home and became a bandit leader. During this time, he made friends who later became important in his military group.

The Chinese empire became weak after the Boxer rebellion. Bandit groups became the main military force in the area. So, the government tried to recruit them. Zhang's bandit groups joined the regular army in 1903. After the Russo-Japanese War, Zhang's forces were a mix of regular soldiers and an outlaw gang.

He played a big part in the 1911 Revolution in Fengtian. In 1916, he became the Civil and Military Governor of Fengtian. By 1919, he controlled the three northeastern provinces: Fengtian, Jilin, and Heilongjiang. He ruled these areas as the commander-in-chief of the Fengtian clique until his death in 1928. From 1918, he started to expand his power into Mongolia and northern China. By early 1925, he was the most powerful military leader in the north. However, he became a main target for the Kuomintang’s Northern Expedition in 1926. This campaign was against the Beiyang government, which Zhang controlled.

Zhang influenced national politics because of the many resources he got from the northeast. This area was rich, had few people, and was developing fast. He also had protection from the Japanese. He gathered a group of loyal military and civilian leaders around him. He strongly stopped city protests that spread across the country in 1925. He believed these protests were led by anti-nationalist and communist groups. Japan strongly supported him in the mid-1920s. The Japanese saw Zhang as the best person to protect their interests compared to other military leaders.

Zhang became less friendly with the Japanese. They wanted him to focus on Manchuria and their interests, not his national goals. In 1928, Japanese officers from the Kwantung Army killed Zhang. This happened while he was retreating to his bases in the northeast. He was trying to escape the attack by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. His son, Zhang Xueliang, then controlled the northeastern provinces until 1931.

Contents

Early Life and Rise to Power

Growing Up in China

Zhang was born in 1875 in Haicheng. This was a county in southern Fengtian province, now called Liaoning. His parents were poor. He did not get much formal education. The only non-military skill he learned was a little bit of animal care. His family had moved to the northeast in 1821 to escape a famine. As a child, Zhang was called "Pimple." He spent his youth hunting, fishing, and fighting. He hunted hares to help feed his family. He was thin and short.

Zhang said he was a Han Chinese Bannerman.

When he was old enough, he worked at an inn's stable. There, he met many bandit groups in Manchuria. By 1896, Zhang himself was part of a known bandit group. One story says he became a bandit after killing a wounded bandit and taking his horse. By his late 20s, he had his own small army. He was seen as a bit of a Robin Hood figure. People called his time as a bandit his "University of the Green Forest" because he couldn't read or write.

In 1900, the Boxer Rebellion started. Zhang's gang joined the imperial army. In peacetime, he hired his men out as guards for traveling merchants. During the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), the Japanese Army hired Zhang and his men as paid soldiers. By the end of the Qing dynasty, Zhang got his men recognized as a regular Chinese army regiment. They patrolled Manchuria's borders and stopped other bandit groups. An American surgeon, Louis Livingston Seaman, met Zhang during the war. He took photos and wrote about his journey.

Gaining Control in Manchuria

During the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, some military leaders wanted Manchuria to be independent. But the pro-Manchu governor used Zhang's soldiers. They formed a "Manchurian People's Peacekeeping Council." This group scared away rebels and revolutionaries. Because he helped prevent trouble, Zhang was made Vice Minister of Military Affairs.

On January 1, 1912, Sun Yat-sen became the first President of the Republic of China in Nanjing. Yuan Shikai, based in Beijing, sent messages to other northern military leaders. He told them to oppose Sun's government. To get Zhang's loyalty, Yuan sent him many military supplies. Zhang sent Yuan a very expensive ginseng root in return. This showed their friendship. Zhang then killed several important people in his home city of Shenyang. The nearly gone Qing court gave him many impressive titles. When Zhang saw that Yuan would take control of the central government, he supported Yuan. He chose Yuan over Sun or the Manchus. After Zhang stopped a rebellion in June 1912, Yuan made him a Lieutenant-General. In 1913, Yuan tried to move Zhang away from Manchuria. He wanted to transfer him to Mongolia. But Zhang reminded Yuan of his success in keeping order. So, Zhang refused to move.

In 1915, Yuan wanted to declare himself emperor. Zhang was one of the few officials who supported him. Zhang saw Yuan as a strong, unifying, and rightful leader. Yuan had also made him military governor of Fengtian for his support. Zhang's main rival in Manchuria, Zhang Xiluan, had been asked about Yuan's plans. He suggested Yuan "think about it more." Because of this, Zhang Xiluan was called back to Beijing. Zhang Zuolin was then promoted.

In March 1916, many southern provinces rebelled against Yuan Shikai. Zhang supported Yuan. But he forced out a local military governor sent by Duan Qirui to replace him. Some local Japanese officers helped him. Beijing accepted Zhang's power. Yuan made Zhang superintendent of military affairs in Liaoning (then called "Fengtian"). After Yuan died in June 1916, the new government named Zhang both military and civil governor of Liaoning. These were key roles for a successful warlord.

Zhang was practical and always friendly with Puyi, the last Emperor of China. He sent Puyi a gift of £1,600 for his wedding. This showed his loyalty. Zhang wanted good relations with Puyi to gain power and legitimacy. In 1917, he planned with Zhang Xun, a Qing-loyal general, to put Puyi back on the throne. Zhang Zuolin suggested talking to the National Assembly about it. After Zhang Xun rebelled, Zhang Zuolin stayed neutral. He supported Duan Qirui in stopping Zhang Xun when it was clear Duan would win. Zhang was able to take in soldiers from nearby commanders linked to the rebellion. This made him more powerful. He took control of China's northernmost province, Heilongjiang, after a rebellion there. The governor of Jilin province was also linked to the attempt to restore the monarchy. Zhang's allies from Jilin successfully pushed for the governor's removal in Beijing. By 1918, Zhang fully controlled Manchuria. Only small areas held by the Japanese Empire were outside his control.

Manchuria: A Stronghold

By 1920, Zhang was the supreme ruler of Manchuria. The central government recognized this. They made him Governor-General of the Three Eastern Provinces. He started living in luxury. He built a large home near Shenyang. He had at least five wives, which was common for powerful Chinese men then. In 1925, his personal wealth was estimated at over 18 million yuan.

His power came from the Fengtian Army. This army had about 100,000 men in 1922. By the end of the decade, it had almost 300,000 men. It had many weapons left from World War I. It also included naval units, an air force, and weapon factories. Zhang brought many local militias into his army. This kept Manchuria from falling into the chaos that was happening in the rest of China. Jilin province was ruled by a military governor, said to be Zhang's cousin. Heilongjiang had its own regional warlord, who only cared about his province.

Manchuria was officially part of the Republic of China. But it became almost an independent state. It was separated from China by its geography and protected by the Fengtian Army. The only pass at Shanhaiguan, where the Great Wall meets the sea, could be easily closed. At a time when the central government could barely pay its workers, no more money was sent to Beijing. In 1922, Zhang took control of the only railway link, the Beijing–Shenyang Railway, north of the Great Wall. He also kept the tax money from this railway. Only postal and customs money kept being sent to Beijing. This was because they had been promised to foreign powers after the failed Boxer Rebellion of 1900. Zhang feared foreign intervention.

In 1922, the Bogda Khan and Bodo suggested that Zhang Zuolin's area (the "Three Eastern Provinces") take control of Outer Mongolia. This happened after pro-Soviet Mongolian Communists took control of Outer Mongolia.

Foreign Influences

Manchuria shared a long border with Russia. Russia's military was weak after the October Revolution. The Chinese Eastern Railway, controlled by Russia, ran through northern Manchuria. The land next to the tracks was considered Russian territory. From 1917 to about 1924, the new Communist government in Moscow had trouble establishing itself in Siberia. It was often unclear who was running the railway on the Russian side. Still, Zhang avoided conflict. After 1924, the Soviets regained control over the railroad.

The Japanese caused more problems. After the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05, they gained two important areas in south Manchuria. The Kwantung Leased Territory was a 218 square mile (565 km2) peninsula in the southernmost part of Manchuria. It included the ice-free port of Dairen (Chinese: Dalian), which was the main link to Japan. North from this colony, the South Manchurian Railway passed through Shenyang (called Mukden by the Japanese). It connected with the Chinese Eastern Railway in Changchun. The land along the railway tracks was controlled by the Japanese. This land was controlled by the Japanese Kwantung Army. This army kept 7,000-14,000 men in Manchuria. They tolerated the Fengtian Army, and the Fengtian Army tolerated them. But Zhang often spoke out against Japan, playing on anti-Japanese feelings among the Chinese people.

Economic Improvements

In the early 1920s, Zhang changed Manchuria. It went from an unimportant border area to one of China's most successful regions. He started with a financially weak government. In 1917, Fengtian owed over 12 million yuan in loans from foreign banks. Zhang chose Wang Yongjiang, who had managed a tax office, to fix Fengtian's money problems. Wang was made director of the finance bureau.

Many different currencies were used in the province. Paper money from the government was losing value. Wang decided to use a silver standard. He set the value of the new silver yuan equal to the Japanese gold yen. This Japanese currency was used in Korea and Manchuria. Surprisingly, the new Chinese money even gained value against the gold yen. Japanese business people said it didn't have enough silver to back it up. Wang then used this new trust to introduce another paper note, the Fengtian dollar. This one could not be changed into silver. However, the government accepted it for tax payments, showing faith in its own money.

Next, Wang improved the messy tax collection system. From his old job, he knew about the problems. He put in place new controls. The government had also invested in many businesses. Many of these were not well managed. Wang ordered a review of these government-backed companies. From 1918, money coming in steadily increased. By 1921, all old loans were paid off, and there was even extra money in the budget. Wang was rewarded by being made Civil Governor of Fengtian province. He also stayed as finance director. Still, more than two-thirds of the budget went to the military.

Challenges and Decline

In 1919, France left some Renault FT tanks in Vladivostok. Zhang Zuolin soon added them to the Manchurian Army.

In the summer of 1920, Zhang went into North China, past the Great Wall. He tried to remove Duan Qirui, the main warlord in Beijing. He helped another warlord, Cao Kun, with troops. They successfully forced Duan out. As a reward, Zhang gained control over most of Inner Mongolia, west of Manchuria.

In December 1921, Zhang visited Beijing. At his request, the entire government, led by Jin Yunpeng, resigned. This allowed Zhang to appoint a new government. He put Liang Shiyi in charge and suggested a new constitution. He also wanted to fix China's money problems. Now a national figure, he soon clashed with Wu Peifu. Wu was a commander of the North China Zhili clique, based in the province of Zhili around Beijing.

In spring 1922, Zhang became the Commander-in-Chief of the Fengtian Army. On April 19, his forces entered China proper. His men took Beijing three days later, and fighting began. On May 4, the Fengtian Army was badly defeated by the Zhili Army. This was called the First Zhili–Fengtian War. Three thousand of Zhang's troops were killed, and 7,000 were wounded. His units retreated to Shanhai Pass. Zhili forces controlled Beijing. Zhang's image as a national leader was ruined. He reacted by declaring Manchuria independent from Beijing in May 1922.

On June 22, Wang Yongjiang left Shenyang for Japanese-controlled Dalian. He said it was for eye treatment. From there, he challenged Zhang. He demanded limits on military spending and full control over civil matters. Zhang gave in. He ended martial law and agreed to separate civil and military rule in all three provinces. Wang returned on August 6, which helped keep Manchuria stable.

Developing the Region

In the years that followed, Wang Yongjiang carried out a big development plan. He tried to bring more workers to Manchuria's growing economy. Most workers came temporarily, returning to North China in winter. The Manchurian government now encouraged them to bring families and settle permanently. As an incentive, they got cheaper train fares on Chinese-owned railways in Manchuria. They also received money to build homes. They were promised full ownership after five years of living there. Rent for the land was canceled for the first few years. Most were sent to inner Manchuria. There, they cleared land for farming or worked in forests or mines. Between 1924 and 1929, the amount of farmed land grew from 20 million acres (81,000 km2) to 35 million acres (140,000 km2).

Manchuria's economy grew rapidly. Meanwhile, the rest of China was in chaos. An especially big project was to break Japan's control over cotton textiles. They built a large mill, which succeeded, much to Japan's dismay. The government also invested in other businesses, including many Chinese-Japanese companies. During this time, the Fengtian Army successfully stopped many bandits in Manchuria. Various railway lines were built, like the Shenyang-Hailong line, which opened in 1925. In 1924, Wang combined three regional banks into the Official Bank of the Three Eastern Provinces. He became its general director. He aimed to create a development bank and keep accurate records of military spending.

The Final Years

After the big defeat in 1922, Zhang reorganized his Fengtian Army. He started a training program and bought new equipment. This included mobile radios and machine guns. In autumn 1924, fighting broke out again in Central China. Zhang saw a chance to take North China and Beijing. He wanted to become the head of the central government. While most other warlord armies fought along the Yangtze River, Zhang attacked North China. This started the Second Zhili–Fengtian War.

In a surprise move, a Zhili commander, Feng Yuxiang, overthrew Cao Kun and took control of Beijing. He shared power with Zhang. Both appointed the same Duan Qirui whom Zhang had removed in 1920. Zhang bought 14 more FT tanks in 1924 and 1925 for the army. They were used in battles.

By August 1925, the Fengtian Army controlled four large provinces inside the Great Wall. These were Zhili (where Beijing was, but not Beijing itself), Shandong, Jiangsu, and Anhui. One unit even marched as far south as Shanghai. However, the military situation was unstable. Sun Chuanfang, a Zhili clique warlord, pushed back the Fengtian Army. By November, Zhang held only a small part of north China. This included a path connecting Beijing with Manchuria. Attacks on Beijing continued into spring 1926.

Manchuria was put under martial law again. Its economy fell apart because of the endless war. Old taxes were raised, and new taxes were created. Zhang demanded that more paper money be printed, without enough silver to back it. A very serious crisis happened in November 1925. Guo Songling rebelled and ordered his troops to march on Shenyang. The Japanese sent more soldiers to protect their interests in Manchuria. But Zhang managed to stop the revolt in December. Even more seriously, Wang Yongjiang, now the civil governor of Manchuria, realized his nine years of work were wasted. He left Shenyang in February 1926 and resigned. Before his death on November 1, 1927, Wang was very disappointed. He did not reply when Zhang asked him to return. Instead, Wang cut all ties with Zhang.

Death of Zhang Zuolin

After losing his finance expert, Zhang took strong actions. In March 1926, he appointed a new governor. This governor's only job was to give the Fengtian Army large amounts of money. He issued new provincial bonds and forced businesses and towns to buy them. Bank money and railway earnings were taken. More and more paper notes were printed. The best sign of Manchuria's economic decline was the value of the Fengtian dollar. It had started equal to the Japanese gold yen. But by February 1928, 40 yuan was worth only 1 gold yen. In winter 1926, Manchuria's economy collapsed. Workers went on strike. Hungry immigrants flooded back into Shenyang because they couldn't find work.

Zhang gave weapons to anti-Guominjun Muslim rebels. These rebels were led by Ma Tingrang during the Muslim conflict in Gansu (1927–30).

In June 1926, Zhang captured Beijing. There were rumors he planned to declare himself emperor. Instead, a year later, with Kuomintang forces getting closer, he joined his military forces with other warlords. These included Zhang Zongchang and Sun Chuanfang. They formed the National Pacification Army and fought against the Northern Expedition. At the same time, he declared himself Generalissimo of the Republic of China. He became China's internationally recognized leader, acting as a dictator. However, the Nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-shek, attacked his forces. In May 1928, the Fengtian Army had to retreat towards Beijing. Also, Japan pressured Zhang to leave Beijing and return to Manchuria. They sent more soldiers to Tianjin to show they were serious. Zhang left Beijing on June 3, 1928.

The next morning, his train reached the edge of Shenyang. Here, the railway line crossed the Japanese-operated South Manchuria Railroad. In what became known as the Huanggutun incident, Colonel Kōmoto Daisaku, a Japanese officer, planted a bomb. It exploded when Zhang's train passed over a railroad bridge. Zhang was badly hurt and died a few days later. At the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal in 1946, Okada Keisuke said Zhang was killed because the Japanese army was angry. He had failed to stop Chiang's army, which was supported by Moscow. For two weeks, Zhang's death was kept secret while leaders decided who would take power. So, the Fengtian Army officially announced his death on June 21, 1928.

Zhang was followed by his oldest son, Zhang Xueliang. He was known as the "Young Marshal." He became the warlord of Manchuria and head of the now-exiled Beiyang Government. This government did not last long. By July, the Beiyang government made a truce with the Kuomintang. By the end of the year, the Northeast Flag Replacement happened. This officially reunited China under the Kuomintang.

Family and Nicknames

Zhang had six wives and 14 children (eight sons and six daughters). His son and successor was Zhang Xueliang. Another son was Zhang Xueming. Zhang Zuolin was a Buddhist.

He was a practical leader. Zhang supported different groups based on what would give him the most power and legitimacy. He even supported putting the Qing dynasty back on the throne in 1917. His nicknames included the "Old Marshal," "Rain Marshal," and "Mukden Tiger." The American news called him "Marshal Chang Tso-lin, Tuchun of Manchuria."

In Media

Many movies, TV shows, and radio shows tell the story of Zhang Zuolin. Some examples are:

- "The Heroes of Troubled Times (乱世枭雄)": A 485-episode radio show about Zhang Zuolin. It was read by the famous storyteller Dan Tianfang.

- "Young Marshal (少帅)": A 48-episode TV show about both Zhang Zuolin and his son Zhang Xueliang. It first aired in 2015.

- "Legend of the Old Marshal (大帅传奇)": A 20-episode TV show about Zhang Zuolin. It first aired in 1994.

|

See also

In Spanish: Zhang Zuolin para niños

In Spanish: Zhang Zuolin para niños

- Warlord Era

- Zhang Xueliang, his son

- History of the Republic of China