Edmonia Lewis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edmonia Lewis

|

|

|---|---|

| "Wildfire" | |

|

|

| Born |

Mary Edmonia Lewis

July 4, 1844 Town of Greenbush, Rensselaer County, New York, US

|

| Died | September 17, 1907 (aged 63) London, UK

|

| Nationality | American, Mississauga |

| Education | New-York Central College, Oberlin |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Movement | Late Neoclassicism |

| Patron(s) | Numerous patrons, American and European |

Mary Edmonia Lewis, also known as "Wildfire" (born around July 4, 1844 – died September 17, 1907), was an amazing American sculptor. She had a unique background, being of both African-American and Native American (Mississauga Ojibwe) heritage.

Edmonia was born free in Upstate New York. She spent most of her career in Rome, Italy. She was the first African-American and Native American sculptor to become famous across the country and then around the world. She started gaining attention during the American Civil War. By the late 1800s, she was the only Black woman artist recognized in the main American art world. In 2002, a scholar named Molefi Kete Asante included Edmonia Lewis in his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

Her art often showed themes about Black people and Native American people. She created these sculptures in a style called Neoclassical, which was popular at the time.

Contents

Edmonia Lewis: A Talented Sculptor

Her Early Life and Family

Not a lot of clear information is known about Edmonia Lewis's early life. She sometimes told different stories about where she came from. She was born near Albany, New York. She spent most of her childhood in Newark, New Jersey.

Her mother, Catherine Mike Lewis, was of Mississauga Ojibwe and African-American background. She was very skilled at weaving and crafts. Edmonia's father was either Samuel Lewis, who was Afro-Haitian, or Robert Benjamin Lewis, a writer.

By the time Edmonia was nine, both of her parents had passed away. Her two aunts from her mother's side took care of her and her older half-brother, Samuel. Samuel was born in 1835 in Haiti. He became a barber when he was 12.

Edmonia and Samuel lived with their aunts near Niagara Falls, New York, for about four years. They sold Ojibwe baskets and other handmade items to tourists. During this time, Edmonia used her Native American name, Wildfire. Her brother was called Sunshine. In 1852, Samuel moved to San Francisco, California.

Edmonia was lucky because her brother Samuel became very wealthy during the California Gold Rush. He made sure she had everything she needed.

Learning to Be an Artist

In 1856, Edmonia Lewis started a pre-college program at New York Central College. This was a school that supported ending slavery. There, she met many important activists who helped her later in her art career.

Her grades and attendance at Central College were excellent. She studied Latin, French, math, drawing, and public speaking.

In 1859, when Edmonia was about 15, her brother and others who fought against slavery sent her to Oberlin, Ohio. She went to Oberlin Academy Preparatory School and then to Oberlin Collegiate Institute. Oberlin was one of the first colleges in the U.S. to accept women and people of different backgrounds. She changed her name to Mary Edmonia Lewis and began to study art.

Edmonia faced racism and unfair treatment at Oberlin. She and other female students often didn't get to speak in class.

In 1862, an incident happened where two classmates became ill after drinking spiced wine that Lewis served. Edmonia was accused of poisoning them. John Mercer Langston, a lawyer, defended her. The charges were dropped because there was no proof of poisoning.

After this, Edmonia faced more challenges at Oberlin. She was accused of other things, but there was no evidence. Eventually, she left the college. In 2022, Oberlin College gave her a degree, many years after she had left.

Starting Her Art Career in Boston

After college, Lewis moved to Boston in 1864 to become a sculptor. She often told a story about seeing a statue of Benjamin Franklin in Boston. She didn't know what it was, but she decided she could make a "stone man" herself.

Friends helped her meet William Lloyd Garrison, a famous abolitionist. He introduced her to other sculptors and writers who shared her story in newspapers that supported ending slavery. It was hard for her to find a teacher. Finally, she met Edward Augustus Brackett, a sculptor who made marble portraits. He taught her by letting her copy parts of sculptures. She even made her own sculpting tools. Her first piece, a sculpture of a woman's hand, sold for $8.

Lewis was inspired by people who fought against slavery and heroes of the Civil War. She made sculptures of famous abolitionists like John Brown and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. When she met Colonel Shaw, who led an African-American Civil War regiment, she made a sculpture of his head. The Shaw family liked it so much they bought it. Lewis then made copies of the sculpture and sold 100 of them for $15 each. This was her most famous work at the time. The money she earned helped her move to Rome.

Many important women in Boston and New York wrote about or interviewed Lewis. Because of them, articles about her appeared in newspapers that supported equal rights. Lewis knew that some people supported her because of her background, not just her art. She accepted the help but wanted her art to be truly appreciated.

She also found inspiration in the poem The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. She made several sculptures of characters from the poem, which came from Ojibwe legends.

Becoming Famous in Rome

The success of her work in Boston allowed Lewis to travel to Rome in 1866. Her passport said she was a "Black girl sent by subscription to Italy having displayed great talents as a sculptor." She was given space to work in the studio of famous sculptor Hiram Powers. She also set up her own studio in the former space of an 18th-century Italian sculptor. She received help from other artists and supporters.

Lewis spent most of her career in Rome. In Italy, there was less racism, which gave her more opportunities as a Black artist. She felt more freedom there than in the United States. She was Catholic, and Rome allowed her to be closer to her faith. In America, she would have needed to rely on people who supported ending slavery. But in Italy, she could make her own way in the international art world.

She started sculpting in marble, using the neoclassical style. However, she focused on making her sculptures look natural, especially when showing Black and Native American people. The ancient Roman surroundings inspired her. She often showed people in her sculptures wearing robes, like in classical art, instead of modern clothes.

Lewis was special because she insisted on carving her clay and wax models into marble herself. Other sculptors often hired Italian artists to do this. Male sculptors sometimes doubted female sculptors' abilities, accusing them of not doing their own work. Lewis also made sculptures before getting paid for them. She would send them to her supporters in Boston and ask them to raise money for materials and shipping.

While in Rome, Lewis continued to show her African-American and Native American heritage. One of her most famous works, "Forever Free", showed an African-American man and woman breaking free from slavery. Another sculpture, "The Arrow Maker," showed a Native American father teaching his daughter to make an arrow.

Her sculptures sold for a lot of money. In 1873, a newspaper said she had received two $50,000 commissions. Her studio became a popular place for tourists to visit. Lewis had many big art shows, including one in Chicago in 1870 and in Rome in 1871.

In 1872, Edmonia was asked to sculpt the hands of a wealthy abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, and his wife, Ann Carroll Fitzhugh.

The Death of Cleopatra

A big moment in her career was taking part in the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. For this event, she created a huge 3,015-pound marble sculpture called The Death of Cleopatra. It showed the queen dying. This piece shows the moment from Shakespeare's play Antony and Cleopatra, where Cleopatra lets a poisonous snake bite her after losing her crown.

Many people were surprised by Lewis's honest way of showing death, but thousands still came to see the statue. Cleopatra was seen as both beautiful and powerful. Lewis's sculpture was different because it showed the queen in a messy, not elegant, way. This was new compared to how death was usually shown in art at that time. Lewis's sculpture might have been a way to comment on the Centennial Exposition. This event celebrated 100 years of American freedom, even though there had been slavery and a recent Civil War.

After the exhibition, the statue was stored away. It was later moved to another exhibition in Chicago but didn't sell. A gambler bought it to mark the grave of a racehorse named "Cleopatra." The sculpture stayed there for almost 100 years. Later, it was moved to a storage yard where it was damaged by some Boy Scouts who tried to paint it.

A dentist named Dr. James Orland saved the sculpture and kept it safe. Later, a scholar named Marilyn Richardson found it while researching Lewis. The sculpture was eventually given to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1994. It cost $30,000 to fix it and bring it back to its original state.

Later Career and Passing

In 1877, former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant asked Lewis to sculpt his portrait. He posed for her, and he liked her finished work. She also made a sculpture of Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner for an exhibition in Atlanta in 1895.

In the late 1880s, the Neoclassical art style became less popular. Lewis's artwork also became less famous. She continued to sculpt in marble, often making religious art for Catholic churches. A sculpture of Christ she made in 1870 was found in Scotland in 2015. She slowly became less known in the art world. By 1901, she had moved to London.

Not much is known about her last years.

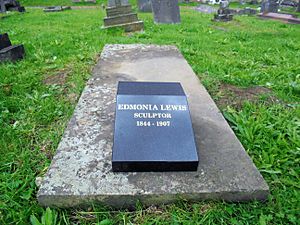

Lewis lived in Paris from 1896 to 1901. Then she moved to Hammersmith in London. She passed away on September 17, 1907, in a hospital there. Her death certificate said she died of kidney failure. She is buried in St. Mary's Catholic Cemetery in London.

For a long time, people thought she had died in Rome or in California.

In 2017, a fundraiser helped restore Edmonia Lewis's grave.

Her Family Life

Lewis never married and did not have any known children. There is no clear information about her romantic relationships.

Her half-brother Samuel became a barber in San Francisco. He later moved to mining towns in Idaho and Montana. In 1868, he settled in Bozeman, Montana, and opened a barber shop. He became successful and bought property. His home, the Samuel Lewis House, is still standing today and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Samuel passed away in 1896.

Famous Sculptures by Edmonia Lewis

Old Arrow-Maker and his Daughter (1866)

This sculpture was inspired by Lewis's Native American background. It shows an arrow-maker and his daughter sitting. They are wearing traditional Native American clothes. The male figure has Native American facial features. However, the daughter does not, because white audiences sometimes misunderstood her work as self-portraits.

Forever Free (1867)

The words "forever free" come from President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which freed enslaved people.

This white marble sculpture shows a man standing, looking up, and raising his left arm. A chain is wrapped around his left wrist, but it is not holding him back. Next to him, a woman is kneeling with her hands together as if praying. The man's right hand is gently on her shoulder. Forever Free celebrates Black freedom and the end of slavery. Lewis wanted to challenge stereotypes about African-American women with this sculpture. It also represents the end of the Civil War. Even though African Americans were legally free, the chains on the figures show that they still faced challenges. This sculpture is at Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C..

Hagar (1875)

Lewis often sculpted strong women from history, like in Hagar and her Cleopatra piece. She also showed ordinary women in tough situations, highlighting their strength. Hagar is based on a character from the Old Testament. Hagar was a servant to Abraham's wife, Sarah. The sculpture is made of white marble. Hagar is standing as if she is about to walk, with her hands clasped in prayer. Lewis used Hagar to represent African mothers in the United States and the difficulties African women often faced.

The Death of Cleopatra (1876)

This important sculpture is talked about in the section above.

Edmonia Lewis in Pop Culture

- A center at Oberlin College for women and transgender people is named after her.

- She is written about in Olio, a poetry book by Tyehimba Jess that won a big award in 2017.

- She was honored with a Google Doodle on February 1, 2017.

- Stone Mirrors: The Sculpture and Silence of Edmonia Lewis (2017) is a book for young people about her life.

- The New York Times published a belated obituary for her in 2018 as part of their "Overlooked" series.

- She is a "Great Artist" in the video game Civilization VI.

- A play about her, called "Edmonia," was performed in Philadelphia in 2021.

- A U.S. postal stamp honoring her was released on January 26, 2022.

List of Major Works

- John Brown medallions, 1864–65

- Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (plaster), 1864

- Anne Quincy Waterston, 1866

- A Freed Woman and Her Child, 1866

- The Old Arrow-Maker and His Daughter, 1866

- The Marriage of Hiawatha, 1866–67

- Forever Free, 1867

- Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (marble), 1867–68

- Hagar in the Wilderness, 1868

- Madonna Holding the Christ Child, 1869

- Hiawatha, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1868

- Minnehaha, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1868

- Indian Combat, Carrara marble, 1868

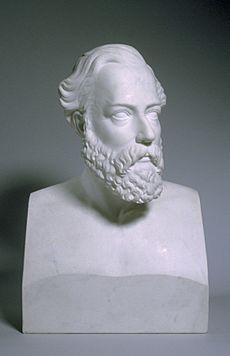

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1869–71

- Bust of Abraham Lincoln, 1870

- Asleep, 1872

- Awake, 1872

- Poor Cupid, 1873

- Moses, 1873

- Bust of James Peck Thomas, 1874, collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum

- Hygieia, 1874

- Hagar, 1875

- The Death of Cleopatra, marble, 1876, collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum

- John Brown, 1876, Rome, plaster bust

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1876, Rome, plaster bust

- General Ulysses S. Grant, 1877–78

- Veiled Bride of Spring, 1878

- John Brown, 1878–79

- The Adoration of the Magi, 1883

- Charles Sumner, 1895

Images for kids

Exhibitions After Her Death

- Art of the American Negro Exhibition, American Negro Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1940.

- Howard University, Washington, D.C., 1967.

- Vassar College, New York, 1972.

- Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, 2008.

- Edmonia Lewis and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Images and Identities at the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1995.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., 1996–1997.

- Wildfire Test Pit, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio, 2016–2017.

- Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, (2019), Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States.

- Edmonia Lewis’ Bust of Christ, Mount Stuart, UK.

See Also

In Spanish: Edmonia Lewis para niños

In Spanish: Edmonia Lewis para niños

- List of female sculptors

- Samuel Lewis House (Bozeman, Montana): Her brother's house in Montana.

- Women in the art history field