Angus Lewis Macdonald facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Angus Lewis Macdonald

|

|

|---|---|

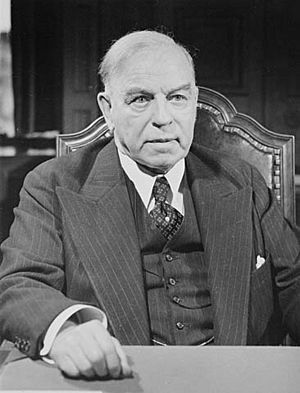

Macdonald in the 1940s

|

|

| 12th and 14th Premier of Nova Scotia | |

| In office September 5, 1933 – July 10, 1940 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Lieutenant Governor |

|

| Preceded by | Gordon S. Harrington |

| Succeeded by | Alexander S. MacMillan |

| In office September 8, 1945 – April 13, 1954 |

|

| Monarch | |

| Lieutenant Governor |

|

| Preceded by | Alexander S. MacMillan |

| Succeeded by | Harold Connolly |

| MLA for Halifax South | |

| In office August 22, 1933 – July 10, 1940 |

|

| Preceded by | District created |

| Succeeded by | Joseph R. Murphy |

| In office October 23, 1945 – April 13, 1954 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph R. Murphy |

| Succeeded by | Richard Donahoe |

| MP for Kingston City | |

| In office August 12, 1940 – June 11, 1945 |

|

| Preceded by | Norman McLeod Rogers |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Kidd |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 10, 1890 Dunvegan, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Died | April 13, 1954 (aged 63) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Agnes Foley Macdonald |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | St. Francis Xavier University |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Canadian Expeditionary Force |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

Angus Lewis Macdonald (August 10, 1890 – April 13, 1954) was an important Canadian politician from Nova Scotia. People often called him 'Angus L.'. He was the leader of the Liberal Party in Nova Scotia.

Macdonald served as the Premier of Nova Scotia twice. First, from 1933 to 1940. Then, during World War II, he became a federal minister in charge of naval services. He helped build a strong Canadian navy. After the war, he returned to Nova Scotia and became premier again in 1945. He was very popular and his party won many elections. He passed away while still in office in 1954.

During his time as premier, Macdonald made big changes. His government spent a lot of money to improve roads, build bridges, and bring electricity to more homes. He also worked to make public education better. He helped people find jobs during the Great Depression by creating highway projects. He believed that direct payments might hurt people's self-respect. Macdonald also argued that poorer provinces like Nova Scotia needed more money from the national government to pay for important services like health and education.

Macdonald was known for his strong speeches. He believed in individual freedom and thought the government should provide basic services.

Contents

Early Life and School

Angus Lewis Macdonald was born on August 10, 1890. He grew up on a small family farm in Dunvegan, Cape Breton Island. He was the ninth of 14 children. His mother came from a well-known Acadian family. His father's family moved to Cape Breton from Scotland in 1810. The Macdonalds were strong Roman Catholics and supported the Liberal Party.

When Angus was 15, his family moved to Port Hood. He went to Port Hood Academy. He wanted to go to St. Francis Xavier University (St. FX), but his family couldn't afford it. So, he became a teacher for two years to earn money for his studies. He even took another year off during university to teach again. He was a great student at St. FX. He played rugby, joined the debating team, and edited the student newspaper. He won many awards and was the top student in his graduating class.

Serving in the War

The First World War started while Macdonald was in university. In 1915, he began military training. In 1916, he joined the 185th battalion, called the Cape Breton Highlanders. He went to Britain for more training. In May 1918, he was sent to the front lines in France as a lieutenant. He fought in heavy battles. Once, he led his whole company because all the other officers were hurt or killed.

Macdonald was lucky for a while, but on November 7, 1918, he was shot in the neck by a German sniper in Belgium. This was just four days before the war ended. He spent eight months recovering in Britain. He returned home to Cape Breton in 1919. The war made him more serious, but also showed him how many people were willing to fight for a cause.

Life Before Politics

In September 1919, Macdonald, then 29, started studying at Dalhousie Law School in Halifax. He made many friends there who later became important politicians. He was excellent in sports and was elected to the student council. He also edited the student newspaper. He did very well in his courses and graduated with honors in 1921.

After law school, Macdonald worked for the Nova Scotia government as an assistant deputy attorney-general. He mostly managed things, but sometimes helped with court cases. In 1922, he started teaching part-time at the law school. In 1924, he became a full-time professor. He was a popular teacher. One student said he would speak slowly and thoughtfully, encouraging students to discuss ideas.

On June 17, 1924, Macdonald married Agnes Foley. She came from a well-known Irish Catholic family. They had worked together in the attorney general's office. Between 1925 and 1936, they had four children. Agnes managed their home and helped Macdonald win elections, especially in areas with many Irish Catholic voters. She was also a great hostess and loved talking with people.

In 1925-26, while teaching, Macdonald took more law courses. He then did graduate work at Harvard Law School in Boston in 1928. Harvard taught that law could improve society. This idea influenced Macdonald's 1929 doctoral paper about property owners' responsibilities.

In 1929, Macdonald thought about becoming the dean of the law school. He had good support. But he was also very interested in politics. Becoming dean would mean putting off his political dreams. He decided to stay at the school for one more year. In 1930, he left so he could enter politics.

Starting His Political Career

Federal Election, 1930

In the summer of 1930, Macdonald, at 40, ran for a federal political job. He decided to run in the Inverness area in his home of Cape Breton Island. He faced a Conservative opponent who was very different from him. Macdonald campaigned hard, but his party, the Liberals, lost the election across Canada. In Inverness, he lost by a small number of votes. This was the only election he ever lost. After this, Macdonald opened his own law office in Halifax.

Becoming Liberal Party Leader

Macdonald was active in the provincial Liberal Party in the late 1920s. In 1925, the party had lost badly after being in power for 43 years. Many believed the party needed to go back to its original goals. Macdonald worked with other younger Liberals to bring the party back to life.

In the 1928 provincial election, the Liberals became more popular. The Conservatives stayed in power, but just barely. When the stock market crashed in 1929, economic problems got worse. It looked like the Liberals would win the next election. Macdonald helped create a 15-point plan for the party. It promised things like an eight-hour workday and free school textbooks. It also planned to study Nova Scotia's economy and its place in Canada.

The party meeting on October 1, 1930, was a big moment for Macdonald. For the first time, delegates at the meeting chose the new party leader. Two older, wealthy businessmen were running, but people weren't very excited about them. Just before nominations closed, someone nominated Macdonald. He was surprised but agreed when he felt strong support. A few hours later, the 40-year-old Macdonald won easily and became the new Liberal leader.

Leading the Liberals

After becoming leader, Macdonald traveled across Nova Scotia. He gave speeches and helped organize party support. He was a very good speaker. People trusted him because he spoke clearly and simply. He could explain political issues so everyone could understand.

When the legislature was meeting, he led the Liberals from the public seating area. He didn't have a seat in the House because there were six empty spots, but the Conservatives wouldn't hold special elections. Macdonald said this was wrong because many Nova Scotians didn't have a voice. He called it "the loss of responsible government." This message was powerful in Nova Scotia, which was the first place in Canada to achieve responsible government in 1848, thanks to Joseph Howe.

Macdonald used this idea even more in the 1933 provincial election. The Conservatives, desperate to win, changed the rules for voter lists. Thousands of Liberal voters were left off the lists. The Liberals got a court order to fix this, and some voters were added. This was called the "Franchise Scandal." It made Macdonald seem like a hero fighting for people's rights, like Joe Howe. This scandal, along with the problems of the Great Depression, helped Macdonald's Liberals win 22 of 30 seats on August 22, 1933. The Conservatives were linked to corruption and hard times. They didn't win power again for 23 years.

First Term as Premier (1933–1937)

Macdonald became Premier of Nova Scotia on September 5, 1933. He was 43 and had never held a seat in the legislature. His cabinet was considered very strong. The ministers were new, motivated, and knew their jobs well. Macdonald's Liberals were given credit for helping Nova Scotia recover from the Great Depression. He was seen as the premier who "paved the roads and put the power into every home."

Pensions and Relief

On his first day, Macdonald kept a promise to bring in old age pensions for elderly people in need. By March 1934, 6,000 pensioners received checks. This was popular, even though Nova Scotia's payments were lower than the national average.

The economy was very bad. Many Nova Scotians were poor and jobless. Macdonald felt sympathy for them. But he worried that direct government payments might hurt their pride. So, his government preferred to hire unemployed people for public projects, like paving roads. In 1933, Nova Scotia had only 45 kilometers of paved roads. By 1937, this grew to 605 kilometers. The government paid for this by selling bonds and raising gasoline taxes.

Macdonald also asked the federal government to give more money to poorer provinces. At that time, there was no national unemployment insurance. The federal government said unemployment was mainly the provinces' job. Nova Scotia and other Maritime provinces got less federal help because they couldn't afford to pay their share for matching grants.

Jones Commission

Macdonald tried to fix the money problems between the provinces and the federal government. He created a special group called the Jones Commission. It was asked to suggest ways to help Nova Scotia's economy and how to talk with the federal government.

The Commission said that high tariffs (taxes on imported goods) helped central Canada's factories but hurt Nova Scotia. They also found that federal money given to Nova Scotia was "seriously inadequate."

The Commission suggested that the federal government should pay for social programs like old-age pensions and unemployment insurance. It also said that Ottawa should treat all provinces fairly. It recommended that federal money should be given based on need, not just population. This idea became very important to Macdonald. The Commission also told Macdonald's government to keep paving roads and bring electricity to rural areas.

Tourism and Nova Scotian Identity

Macdonald's government worked to bring more tourists to Nova Scotia. They gave small loans to hotel and motel owners to improve their places. They also offered cooking classes for restaurant workers. The new paved roads made it easier for tourists to travel.

Macdonald also promoted Nova Scotia as a beautiful, old-fashioned place with friendly people from Scottish, Acadian, German, and Mi'kmaq backgrounds. Government ads showed the province as a place where city families could "step back in time." This helped create a new identity for Nova Scotians. Macdonald especially loved the "romanticized culture of the Highland Scots." His government gave money to the Gaelic College, gave Scottish names to tourist spots, and even put a Scottish piper at the border with New Brunswick. Macdonald also helped create the Cape Breton Highlands National Park. He believed he had made "a piece of Scotland for tourists in the New World." As more tourists came, Macdonald became even more popular.

Trade Union Act

In the 1930s, the Nova Scotia legislature passed an important law for workers called the Trade Union Act. This law protected the rights of unions. Both Macdonald's Liberals and the opposition Conservatives agreed on the need for this law. The new law made employers bargain with any union chosen by most of their workers. It also stopped employers from firing workers for organizing a union.

Government Jobs and Contracts

In Nova Scotia, it was common for governments to give jobs and contracts to their supporters. This continued under Macdonald's Liberals. Road improvements were often used to win votes, especially before elections. Government contracts were given to companies approved by the party. In return, these companies would give some money back to the Liberals. Macdonald himself didn't really like this practice, but it continued.

Second Term as Premier (1937–1940)

The economy improved during the 1930s, which was good for Macdonald's government. In March 1937, Macdonald announced that the Nova Scotia government had made more money than it spent for the first time in 14 years. He promised to spend more money on the popular road paving program. His Minister of Highways, A. S. MacMillan, was also extending electricity to rural areas. He introduced a bill to help pay for rural electricity.

After these preparations, Macdonald called an election for June 29, 1937. He campaigned on his government's good record. His Liberals won 25 of the 30 seats in the legislature.

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King had asked Macdonald to join federal politics in 1935, but Macdonald said no. However, in 1937, there were rumors that Macdonald would soon move to federal politics. Macdonald wanted to stay as premier to present Nova Scotia's case to a special group studying federal-provincial relations.

Rowell-Sirois Commission

The Great Depression showed big problems in how money was shared between the federal government and the provinces. Poorer provinces couldn't handle widespread poverty. By 1937, some provinces were almost bankrupt. So, in August 1937, Prime Minister King created the Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations, known as the Rowell-Sirois Commission. Macdonald played a key role in its final recommendations.

Macdonald wrote Nova Scotia's official statement and presented it himself in Halifax in February 1938. He asked the federal government to take full responsibility for social programs like unemployment insurance and old-age pensions. He also suggested that the federal government should control income taxes to pay for these programs. But he argued that provinces needed to collect other taxes, like sales taxes, to stay independent.

A main part of Macdonald's argument was about sharing wealth from richer provinces to poorer ones. He said that richer provinces benefited from national policies, while poorer ones were hurt. He suggested that money given to poorer provinces should be based on their needs, not just population. This would help them offer the same services as richer provinces without having to tax their citizens more.

The Commission's final report in May 1940 included many of Macdonald's ideas. Prime Minister King called a meeting in January 1941 to discuss the report, but the provinces couldn't agree. In April, the federal government decided to raise taxes on personal and company incomes to pay for Canada's part in World War II.

Called to Ottawa

Macdonald's political path changed when Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939. Three months later, Prime Minister King called a federal election and won easily. King wanted to bring the country's "best brains" into his wartime cabinet. When his defense minister died in June 1940, King had a chance to change his government. He asked J. L. Ralston, a Nova Scotian, to be his new defense minister. Ralston agreed, but only if J. L. Ilsley of Nova Scotia became finance minister, and if he got help in his new job.

King decided to appoint two more ministers: one for the air force and one for the navy. He asked Macdonald to join the federal cabinet as minister of national defense for naval services. Macdonald had fought in World War I. He felt it was his duty to help fight World War II as a political leader in Ottawa. He gave his premier duties to A. S. MacMillan and joined the federal cabinet on July 12, 1940.

Wartime Federal Career (1940–1945)

Macdonald's five years in Ottawa were busy. He oversaw a huge growth in Canada's navy. He also played a key role in a political problem that almost divided the government and the country. He also made Prime Minister King angry. When he joined the cabinet in 1940, Macdonald seemed like he might become prime minister one day. But by the time he left in 1945, his federal political career was not going well.

King wanted Macdonald to run for an empty seat in Kingston, Ontario. This area was usually Conservative. Macdonald said he didn't know Kingston or its people. But when the Conservatives agreed not to run a candidate against him, Macdonald had no choice. He won the seat without opposition on August 12, 1940.

Macdonald had a huge and very important job: expanding the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). When Canada entered the war in 1939, the RCN was tiny. It had only a few ships and about 3,000 people. By the time Macdonald took office in 1940, it had grown to 100 ships and over 7,000 people, but many were not ready for sea. By the end of the war, the RCN had grown 50 times its original size. It had about 400 fighting ships and 96,000 men and women.

The RCN's job was to protect supply ships carrying food and other materials. This convoy duty was vital because German submarines (U-boats) tried to sink these ships to stop supplies from reaching Britain. The RCN did about 40 percent of the transatlantic escort duty for the Allies. This was Canada's most important military contribution.

However, Canada's convoy efforts had problems early in the war. The Canadian navy lacked equipment to find submarines underwater and good radar to spot them on the surface. Also, Canada didn't have long-range aircraft, which were the best weapons against submarines. As supply ships were lost, the RCN worked hard to catch up to the better-equipped British and American navies. Macdonald himself wasn't a military expert. He often relied on senior naval officers who sometimes didn't tell him about equipment problems. As the war went on, the RCN, under Macdonald's leadership, became better at protecting the vital supplies needed for the Allied victory.

Conscription Crisis

Macdonald played a key role in the wartime conscription crises in 1942 and 1944. Prime Minister King tried to avoid forcing people to join the military for overseas service. Macdonald strongly supported conscription (compulsory military service). He believed it was unfair that some people volunteered for overseas service while others didn't. However, Macdonald knew that conscription was very unpopular in French-speaking Quebec. He realized that forcing it would divide the country when national unity was crucial. He also saw that in the early war years, enough people were volunteering.

Still, Macdonald kept pushing the government to commit to conscription if it became necessary. This made Prime Minister King, who was very careful politically, dislike Macdonald. King wrote in his diary that Macdonald was "a very vain man" who expected to lead the Liberal party later.

As the opposition kept pushing for overseas conscription, King's government held a national vote (plebiscite) on April 27, 1942. Voters were asked to release the government from its promise not to introduce compulsory war service. The results showed a clear split: English Canada voted strongly in favor, and French Canada voted strongly against.

The crisis came up again two years later when the military needed more soldiers overseas. Ralston, the defense minister, wanted King to bring in conscription. Macdonald seemed willing to compromise with King's plan for one last voluntary recruitment campaign. However, King suddenly fired Ralston during a cabinet meeting on November 1, 1944. Macdonald thought about resigning, but he stayed. His decision not to resign likely saved King's government. King himself seemed to know that if Macdonald had left, other ministers might have resigned too, causing the government to fall.

In the end, King had to bring in overseas conscription after the voluntary campaign failed. But the war ended soon after, and his government survived. The conscription crisis, however, made the bad feelings between King and Macdonald even stronger. Macdonald was tired of national politics and wanted to return to Nova Scotia. After King called an election for June 11, 1945, Macdonald resigned from the federal cabinet.

Premier Again (1945–1954)

When Macdonald returned to Nova Scotia in 1945, he was 55. After Premier A. S. MacMillan retired, the Liberals confirmed Macdonald as their leader on August 31, 1945. Less than two months later, Macdonald's Liberals won a huge victory across the province. They won almost all the seats, except for two in Cape Breton, where voters chose members of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which is now the New Democratic Party (NDP). Even with this big win, a close friend noticed that Macdonald wasn't the same. He had trouble making decisions because he wasn't well.

Still, Macdonald became a strong voice for the provinces. He argued that provinces needed to control their own taxes, like gasoline, electricity, and entertainment taxes, to stay independent. He pushed for changes to the constitution to protect provincial rights. Macdonald urged the federal government to accept the 1940 recommendations of the Rowell-Sirois Commission. He wanted national wealth to be shared based on need. He said this would help poorer provinces provide the same services as richer ones without higher taxes. In the end, Macdonald only won small victories, like getting control over gasoline taxes. The federal government refused to make financial need the main reason for giving money to provinces.

Besides being a national spokesperson for provincial rights, Macdonald's government invested a lot in education. His government paid for new rural high schools. They also gave financial help to Dalhousie University's medical and law schools. In 1949, Macdonald appointed Nova Scotia's first minister of education, Henry Hicks. This minister oversaw a large part of the provincial budget for education.

The Macdonald Liberals easily won elections in 1949 and 1953. However, the Conservatives, led by Robert Stanfield, started gaining ground. For example, the Conservatives pointed out that brewing companies and wineries gave money to the Liberal party to be allowed to sell their products in government liquor stores. But the Liberals seemed safe as long as the popular Angus L. Macdonald was their leader.

Macdonald had a slight heart attack on April 11, 1954. He went to the hospital and passed away in his sleep two nights later, at age 63.

On the day he died, the Nova Scotia legislature met. Macdonald's seat was covered in a Scottish tartan fabric, and a sprig of heather was on his desk. His body lay in the legislative building for three days. More than 100,000 people came to pay their respects.

After Macdonald's Death

Macdonald's death was very bad for the provincial Liberals. There was no clear person to take over from the popular premier. At the party's leadership meeting on September 9, 1954, the Liberals seemed divided. After five votes, they chose Henry Hicks, a Protestant, instead of Harold Connolly, a Roman Catholic who had been interim premier after Macdonald's death. It looked like the delegates had teamed up against the only Catholic candidate.

Nova Scotia governments often struggled after a change in leadership. In the next provincial election on October 30, 1956, Robert Stanfield and his Conservatives won 24 seats, while the Liberals won 18. The 23-year Liberal era, which began under Macdonald, had finally ended.

His Impact and Legacy

Some historians believe Macdonald's popularity in Nova Scotia was even greater than the legendary Joseph Howe's. Like Howe, Macdonald was a passionate and skilled leader. His speeches showed his cleverness, wide knowledge, and respect for facts. He was known as a leader who always kept his promises.

Macdonald was seen as the premier who led Nova Scotia out of the Great Depression. This was because of his commitment to big government projects like building highways and bringing electricity to rural areas. He continued to support road improvements throughout his career. Two projects he strongly pushed for, the Canso Causeway (linking Cape Breton Island to mainland Nova Scotia) and a suspension bridge across Halifax Harbour, were finished after his death. The bridge, named in his honor, made it much easier to travel between Halifax and Dartmouth.

Macdonald always called for a fairer way to share wealth, so that poorer provinces like Nova Scotia could fully share in Canada's success. He is credited with the introduction of an equalization scheme in 1957. This scheme was designed to help poorer provinces provide similar levels of services to their citizens. However, Macdonald's idea of provincial independence faced challenges as the federal government took more control over national social programs after the war.

Throughout his life, Macdonald stayed connected to his old university, St. Francis Xavier University. He received an honorary law degree from St. FX in 1946. He helped raise money for the university's 100th anniversary in 1953. He also raised money to support student research into the history of Scots in Nova Scotia. Macdonald suggested that a reading room in a new university library be called the Hall of the Clans. St. FX liked the idea and decided to name the entire library after him. So, when the Angus L. Macdonald Library opened on July 17, 1965, its reading room had 50 coats of arms representing Scottish and Irish clans.

Images for kids

-

Statue of Scottish poet Robert Burns in downtown Halifax. Macdonald delivered a memorable speech on "the bard of Scotland" to the North British Society of Halifax on January 25, 1951. The Burns statue was erected by the Society in 1919.

See Also

- Conscription Crisis of 1944

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |