Royal Flying Corps facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Royal Flying Corps |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Active | 13 April 1912–1 April 1918 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Allegiance | King George V |

| Branch | British Army |

| Size | 3,300 aircraft (1918) |

| Motto(s) | Latin: Per Ardua ad Astra "Through Adversity to the Stars" |

| Wars | First World War |

| Disbanded | merged with RNAS to become Royal Air Force (RAF), 1918 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Sir David Henderson Hugh Trenchard |

| Insignia | |

| Roundel |  |

| Flag |  |

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air branch of the British Army during the First World War. It was formed in 1912 and later joined with the Royal Naval Air Service on April 1, 1918. Together, they created the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Early in the war, the RFC helped the British Army by spotting for artillery and taking photos from the sky. This led to RFC pilots fighting in the air against German pilots. Later, they also attacked enemy soldiers and bases, bombed German airfields, and even bombed German factories and transport hubs.

When World War I began, the RFC had five squadrons. One squadron used observation balloons, and four used aeroplanes. They first used planes to spot targets on September 13, 1914. This became much better when they learned to use radio communication in May 1915. Taking photos from the air also became very effective by 1915. By 1918, photos could be taken from 15,000 feet high. Pilots in the RFC did not have Parachutes during the war, even though balloonists had used them for three years.

In August 1917, General Jan Smuts suggested creating a new air service. He believed air power could cause "vast destruction" to enemy lands. He recommended a new service equal to the Army and Navy. This new service would also use the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) planes and people more effectively. On April 1, 1918, the RFC and RNAS combined to form the Royal Air Force (RAF). In 1914, the RFC had about 2,073 people. By early 1919, the RAF had 4,000 combat aircraft and 114,000 people.

Contents

- How the Royal Flying Corps Started

- Aircraft Used by the RFC

- How the RFC Grew and Organized Itself

- The Royal Flying Corps in World War I

- Recruitment and Training

- Parachutes

- End of the War

- Commanders and Notable People

- RFC in Books, Movies, and Games

- Songs

- See also

How the Royal Flying Corps Started

People realized that aircraft could be very useful for scouting and helping artillery. So, in November 1911, a group was set up to study military aviation. On February 28, 1912, they suggested creating a flying corps. This corps would have a naval part, a military part, a central flying school, and an aircraft factory.

These ideas were accepted. On April 13, 1912, King George V officially started the Royal Flying Corps. A month later, the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers became the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps.

The RFC was first allowed to have 133 officers. By the end of 1912, it had 12 manned balloons and 36 aeroplanes. The RFC's first leader was Brigadier-General Henderson. It had separate parts for the Army and the Navy. However, the Royal Navy wanted more control over its aircraft. So, on July 1, 1914, their part officially became the Royal Naval Air Service.

The RFC's motto was Per ardua ad astra, which means "Through adversity to the stars." This is still the motto of the Royal Air Force (RAF) today.

The RFC had its first fatal crash on July 5, 1912, near Stonehenge. Captain Eustace B. Loraine and Staff Sergeant R.H.V. Wilson died. After the crash, an order was given: "Flying will continue this evening as usual." This started a tradition.

Aircraft Used by the RFC

Many different types of aircraft were used by the RFC during the war. Here are some of them:

- Airco DH 2, DH 4, DH 5, DH 6, and DH 9

- Armstrong-Whitworth F.K.8

- Avro 504

- Bristol's Bristol Scout (a single-seat fighter), F2A and F2B Fighter (two-seaters)

- Handley Page O/400

- Martinsyde G.100

- Morane-Saulnier Bullet Biplane Parasol

- Nieuport Scout 17, 24, 27

- Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2a, B.E.2b, B.E.2c, B.E.2e, B.E.12, F.E.2b, F.E.8, R.E.8, S.E.5a

- Sopwith Aviation Company 1½ Strutter, Pup, Triplane, Camel, Snipe, Dolphin

- SPAD S.VII

- Vickers FB5

How the RFC Grew and Organized Itself

When it started in 1912, the Royal Flying Corps had a Military Wing and a Naval Wing. The Military Wing had three squadrons. The Naval Wing, with fewer planes, formed its own squadrons in 1914 and then separated from the RFC.

By November 1914, the RFC had grown enough to create "wings," which were groups of two or more squadrons. These wings were led by lieutenant-colonels. By October 1915, the RFC had grown even more, leading to the creation of "brigades," each led by a brigadier-general.

The RFC continued to expand, creating "divisions" like the Training Division in 1917. By March 1916, the RFC in France was so large it acted like a division. The need for air units kept growing throughout World War I. The last RFC wing was created in March 1918, just before the RAF was formed.

Squadrons

Two of the first three RFC squadrons were formed from the Royal Engineers' Air Battalion. For example, No. 1 Company (a balloon company) became No. 1 Squadron, RFC. By the end of March 1918, the Royal Flying Corps had about 150 squadrons.

An RFC squadron's size changed based on its job. A major usually commanded it, but the actual flying was done by "flights" (like A, B, C), each led by a captain. Each flight had about six to ten pilots. A squadron also had officers and many other ranks for administration, maintenance, and transport.

Wings

Wings in the Royal Flying Corps were made up of several squadrons. When the RFC was first created, it was meant to be a joint service for both the Army and Navy. However, the Navy soon formed its own separate Royal Naval Air Service in 1914.

As the Flying Corps grew, new "wings" were created to control groups of squadrons. For example, the 1st Wing and 2nd Wing were formed in France to support the British Armies. More wings were created throughout the war, with the 54th Wing being the last one in March 1918.

Later, wings took on special jobs. "Corps wings" helped with artillery spotting and ground communication. "Army wings" focused on air battles, bombing, and long-range scouting. Wings in the UK were for home defense and training.

Brigades

In August 1915, a plan was made to expand the RFC's command structure. Wings would be grouped into "brigades," led by a brigadier-general. This plan was approved and put into action.

In the field, most brigades were assigned to the army. They usually included an army wing and a corps wing. Later, a balloon wing was added to control observation balloon companies.

Stations and Airfields

All RFC operating locations were called "Royal Flying Corps Station name." A squadron might use an aerodrome for its headquarters and several "Landing Grounds" for its flights. Stations were often named after local railway stations for easy travel.

A typical training airfield was a 2000-foot grass square. It had hangars made of wood or brick, and temporary canvas hangars. Other buildings were usually wooden huts. Landing Grounds were often simpler, sometimes just a field with a hedge removed. They were usually manned by a few airmen to guard fuel and help landing aircraft.

Training Locations

The RFC set up training air stations in Canada in 1917 to train aircrew. These included:

- Camp Borden (1917–1918)

- Armour Heights Field (1917–1918)

- Leaside Aerodrome (1917–1918)

- Long Branch Aerodrome (1917–1918)

- Camp Rathbun, Deseronto (1917–1918)

- Camp Mohawk (now Tyendinaga (Mohawk) Airport) (1917–1918)

- Hamilton (Armament School) (1917–1918)

- Beamsville Camp (School of Aerial Fighting) (1917–1918)

Other training locations were in:

- St-Omer, France (headquarters)

- Ismailia, Egypt

- Aboukir, Egypt

- Abu Sueir, Egypt

- El Ferdan, Egypt

- El Rimal, Egypt

- Camp Taliaferro, North Texas, USA

The Royal Flying Corps in World War I

The RFC was also in charge of operating observation balloons on the Western Front. These balloons were very risky to use and often got damaged. They were good for taking photos because they were stable, unlike planes.

In the first half of the war, the French air force was much larger than the RFC. Despite having basic aircraft, the RFC's commander, Hugh Trenchard, pushed for aggressive attacks. This led to many brave actions but also high casualties, especially in April 1917, which was called 'Bloody April'. However, this aggressive approach gave the Army important information about German positions through constant scouting and photos.

Early Actions with the British Expeditionary Force

At the start of the war, Squadrons 2, 3, 4, and 5 had aeroplanes. Squadron 1, which used to have balloons, became an 'aircraft park' for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The RFC had its first casualties before even reaching France. On August 12, 1914, Lt Robert R. Skene and Air Mechanic Ray Barlow died in a crash.

On August 13, 1914, 60 RFC planes left Dover for France. On August 19, the RFC flew its first scouting mission. On August 22, 1914, the first British aircraft was shot down by German fire. Also on that day, Captain L E O Charlton and Lieutenant Vivian Hugh Nicholas Wadham made a key discovery. They saw the German 1st Army moving towards the British forces. This helped the British commander, Sir John French, save his army near Mons.

On August 25, the RFC got its first air victory. Lieutenants C. W. Wilson and C. E. C. Rabagliati forced down a German plane. After the retreat from Mons, the RFC continued to prove its worth. Their information helped the French forces counter-attack at the Battle of the Marne.

Sir John French praised the RFC's work, saying their "skill, energy, and perseverance has been beyond all praise."

Aircraft Markings

Early in the war, RFC aircraft did not have standard national markings. Sometimes, Union Flags were painted on the wings. But the large red St George's Cross looked too much like the German Eisernes Kreuz (iron cross). This meant RFC planes were sometimes shot at by their own side.

By late 1915, the RFC started using a modified version of the French roundel. The colors were reversed, with the blue circle on the outside. This roundel was put on the sides of the fuselage and the wings. To avoid friendly fire, the rudders of RFC aircraft were painted like the French flag, with blue, white, and red stripes. Later, a "night roundel" was used for night flying, which removed the bright white circle.

What the RFC Did: Roles and Responsibilities

Wireless Telegraphy

In September 1914, during the First Battle of the Aisne, the RFC used radio to help aim artillery. They also took aerial photographs for the first time. Early radios were heavy, so the pilot had to fly, navigate, observe, and send Morse code messages all by himself. The aircraft radios could not receive messages.

Later, lighter radios became available. By 1915, each army corps had an RFC squadron just for artillery observation and scouting. A key development was the "Zone Call" procedure in 1915. Pilots could report target locations using Morse code. Ground crews near the artillery batteries would receive these calls and help the gunners adjust their aim.

Photo-Reconnaissance

From 16,000 feet, a single photo could cover a large area of the front line in great detail. In 1915, Lieutenant-Colonel JTC Moore-Brabrazon designed the first practical aerial camera. These cameras became very important for the RFC. The camera was usually fixed to the side of the plane or shot through a hole in the floor. Aerial photos were essential for making detailed maps for the British Army. The entire Somme Offensive in 1916 was planned using RFC air photos.

Aerial Bombardment

The RFC quickly saw the potential for bombing the enemy. Even though early planes couldn't carry much, bombing missions were carried out. Pilots found ways to carry and drop bombs. For example, Lieutenant Conran dropped hand grenades on enemy troops, causing their horses to panic. Captain Louis Strange destroyed two trucks with homemade petrol bombs.

In March 1915, Captain Strange flew a bombing raid, carrying four 20 lb bombs. He attacked Courtrai railway station and hit a troop train, causing many casualties. Days later, Lieutenant William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse was awarded the Victoria Cross for bombing Courtrai station.

In October 1917, No 41 Wing was formed to attack important targets in Germany. This wing included squadrons with different aircraft types, like the Airco DH.4 and Handley Page 0/100 bombers. They attacked German cities and factories.

Ground Attack – Army Support

As the war continued, aircraft were used more and more to attack enemy forces on the ground. These attacks were usually done by single pilots or small groups against targets they saw. Machine guns were the main weapon, but many single-seat planes also carried 20 lb bombs.

Ground attacks were flown at very low altitudes and were often very effective. They had a big impact on the morale of ground troops. However, these missions were very dangerous for the planes, as even small arms fire could bring them down. During the Battle of Messines in June 1917, RFC planes flew low and attacked all available targets.

During the Third Battle of Ypres, over 300 aircraft from 14 RFC squadrons constantly attacked enemy trenches, troop groups, and artillery. This was done in cooperation with tanks and infantry. These ground attacks were costly for the RFC, with nearly 30% of aircraft being lost.

Home Defence

In the UK, the RFC was responsible for training air and ground crews. They also had to defend the country against German Zeppelin and Gotha raids. The RFC had trouble finding the German raiders and getting planes that could fly high enough to reach them.

Most operational squadrons were in France, so training squadrons had to provide planes and crews for home defense in the UK. These night flying missions were often flown by instructors in older aircraft. The RFC officially took over Home Defence in December 1915 and had 10 permanent airfields.

Saint-Omer Headquarters

As the war moved, the RFC moved its headquarters to Saint-Omer, France, in October 1914. For the next four years, Saint-Omer was a central point for all RFC operations in the field. It grew in importance as it provided more and more support to the RFC.

Trenchard's Command in France

Hugh Trenchard led the Royal Flying Corps in France from August 1915 to January 1918. Trenchard focused on three main things:

- Supporting ground forces: This included scouting, helping artillery, and later, low-level bombing of enemy troops.

- Boosting morale: He believed that the presence of aircraft helped his own airmen's morale and hurt the enemy's.

- Offensive action: Trenchard strongly believed in attacking the enemy. While this led to many losses, it also provided vital information to the Army.

1916–1917: The War Continues

Before the Battle of the Somme, the RFC had 421 aircraft and 14 observation balloons. By the end of the Somme offensive in November 1916, the RFC had lost 800 aircraft and 252 aircrew. They dropped 292 tons of bombs and took 19,000 reconnaissance photos.

In 1917, the German Air Force became stronger with new fighter planes like the Albatros. This caused very heavy losses for the RFC's older aircraft, especially in April 1917, known as 'Bloody April'. To support the Battle of Arras in April 1917, the RFC used 25 squadrons with 365 aircraft. The British lost 245 aircraft, while the Germans lost only 66.

By summer 1917, new advanced aircraft like the SE5, Sopwith Camel, and Bristol Fighter were introduced. This helped reduce losses and increase damage to the enemy. By November 1917, low-flying fighter planes worked very well with tanks and infantry during the Battle of Cambrai. In 1917, 2,094 RFC aircrew were killed or went missing.

RFC in Italy and Other Areas

After the Italian Army's defeat in the Battle of Caporetto, three RFC fighter squadrons and two two-seater squadrons were sent to the Italian Front in November 1917. RFC squadrons were also sent to the Middle East and the Balkans. In July 1916, the Middle-East Brigade of the RFC was formed to combine all RFC units in these areas.

In the Middle East, units often had to use older aircraft before getting more modern ones. The Palestine Brigade was formed in October 1917 to support General Allenby's attacks against the Ottomans. Despite their smaller numbers, the RFC greatly helped the Army defeat Ottoman forces in Palestine, Trans Jordan, and Mesopotamia (Iraq).

1918: The Final Push

The German Spring Offensive in March 1918 was a huge effort by Germany to win the war. RFC crews flew constantly, bombing and attacking ground forces, often from very low heights. They also brought back important reports about the changing battle on the ground.

The RFC played a big part in slowing the German advance and ensuring the Allied armies could retreat in an organized way. The battle was most intense on April 12, when the newly formed RAF dropped more bombs and flew more missions than on any other day during the war. However, stopping the German advance came at a high cost, with over 400 aircrew killed and 1000 aircraft lost.

Joining Forces: RFC and RNAS Become RAF

On August 17, 1917, General Jan Smuts suggested creating a new air service. He believed air power could cause "vast destruction" to enemy lands. He recommended a new service equal to the Army and Royal Navy. This new service would also use the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) planes and people more effectively. On April 1, 1918, the RFC and the RNAS combined to form the Royal Air Force (RAF). In 1914, the RFC had about 2,073 people. By early 1919, the RAF had 4,000 combat aircraft and 114,000 personnel.

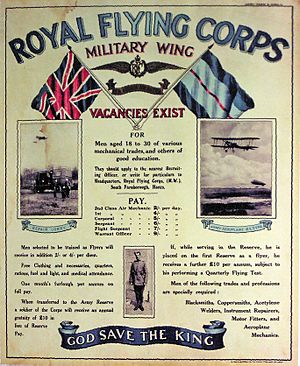

Recruitment and Training

Many pilots first joined the RFC as observers, often from other regiments. Some RFC ground crew also volunteered for flying duties to get extra pay. There was no formal training for observers until 1917. Many were sent on their first flight with just a quick introduction from the pilot. Once an observer was fully qualified, they received a special "half-wing brevet" badge.

Initially, the observer was technically in charge of the aircraft, with the pilot acting as a "chauffeur". However, this quickly changed, and the pilot became the commander. Most two-seater planes didn't have dual controls, so if the pilot was hurt, the plane would crash. But many observers learned basic flying skills and often went on to become pilots themselves.

New aircrew applicants usually started as cadets for basic training. They would then go to a School of Military Aeronautics for classroom learning. After that, they were sent to a Training Squadron in the UK or overseas.

Colonel Robert Smith-Barry created a full training program for pilots in 1917. This program greatly reduced training accidents. It combined classroom theory with dual flight instruction. Students were taught how to handle dangerous situations safely. About 45% of cadets were found not suitable for flying during this training. After 10 to 20 hours of dual instruction, students were ready to fly solo.

In May 1916, pilots also received training for air combat. Special Flying Schools were set up where pilots could practice combat flying with experienced instructors. In 1917, experienced pilots from the Sinai and Palestine campaign helped set up new flying schools in Egypt and Australia.

Between 1917 and 1919, Camp Borden in Canada trained 1,812 RFC Canada pilots and 72 for the United States. Training was dangerous; 39 RFC officers and cadets died in Texas. Many men from across the British Empire, including South Africa, Canada, and Australia, joined the RFC. Canadians made up almost a third of RFC aircrew.

Even with safer training methods later in the war, about 8,000 people were killed in training or flying accidents by the end of the war.

Parachutes

Before the war, parachuting from balloons and aircraft was a popular stunt. In 1915, inventor Everard Calthrop offered his parachute to the RFC. On January 13, 1917, Captain Clive Franklyn Collett made the first British military parachute jump from a plane. It was successful.

However, even though parachutes were given to observation balloon crews, the RFC leaders did not want to give them to pilots of planes. They worried that a parachute might make a pilot abandon their aircraft instead of continuing to fight. Also, early parachutes were heavy and bulky, which could affect the performance of planes that were already not very powerful. It wasn't until September 16, 1918, that an order was given for all single-seater aircraft to have parachutes, but this didn't happen until after the war.

End of the War

By the end of the war, there were 5,182 pilots in service. From 1914 to 1918, the RFC/RNAS/RAF had 9,378 people killed or missing, and 7,245 wounded. They flew 900,000 hours on operations and dropped 6,942 tons of bombs. The RFC claimed to have destroyed or driven down about 7,054 German aircraft and balloons.

Eleven RFC members received the Victoria Cross during World War I. The RFC didn't initially publicize the victories of their aces. But public interest led to this policy changing. The achievements of aces like Captain Albert Ball boosted morale. Over 1,000 airmen are considered "aces."

For a short time after the RAF was formed, old RFC ranks like Lieutenant and Captain still existed. This officially ended on September 15, 1919.

Commanders and Notable People

Commanders of the RFC in the Field

- Major General Sir David Henderson, August 5, 1914 – November 22, 1914

- Colonel F H Sykes, November 22, 1914 – December 20, 1914

- Major General Sir David Henderson, December 20, 1914 – August 19, 1915

- Brigadier General, later Major General, H M Trenchard, August 25, 1915 – January 3, 1918

- Major General J M Salmond, January 18, 1918 – January 4, 1919 (became General Officer Commanding the RAF in the Field from April 1)

Some Famous RFC Members

- Albert Ball, VC – a top ace with 44 victories.

- Billy Bishop, VC – one of the highest-scoring British Empire flying aces of World War I.

- Hugh Dowding – later led RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain.

- Lanoe Hawker VC, DSO – the first British ace, shot down by the "Red Baron."

- James McCudden VC – a top ace with 57 victories.

- Edward Mannock VC – often considered one of the highest-scoring British Empire aces.

- Sir Charles Kingsford Smith – an Australian aviation pioneer who was the first to fly across the Pacific Ocean.

- Robert Smith-Barry – created a formal system for pilot training.

- William Stephenson – led British Security Coordination during World War II.

- Hubert Williams (1895–2002) – the last surviving Royal Flying Corps pilot.

RFC in Books, Movies, and Games

Novels and Short Stories

- Winged Victory (1934) by Victor M Yeates, a World War I pilot.

- The Biggles series (1932–1999) by W. E. Johns, an RFC veteran.

- The Bandy Papers (1962–2005) by Donald Jack, about a fighter ace.

- Goshawk Squadron (1971) by Derek Robinson.

- The Bloody Red Baron (1995) by Kim Newman, a fantasy novel.

- Phoenix and Ashes (2004) by Mercedes Lackey, a fantasy novel.

- Across the Blood-Red Skies (2010), by Robert Radcliffe.

Film and TV

- Hell's Angels (1930): a film by Howard Hughes.

- The Dawn Patrol (1938): a film starring Errol Flynn.

- "The Last Flight" (1960): an episode of The Twilight Zone.

- Aces High (1976): a film starring Malcolm McDowell.

- Wings (1977–78): a BBC TV series.

- "Private Plane" (1989): an episode of the Blackadder TV series.

- "The Double Deuce" (2011) : an episode of the Archer TV series.

Games

- Battlefield 1

Songs

- The Hymn of Hate (1918)

See also

- Army Air Corps

- Canadian Aviation Corps

- Royal Canadian Naval Air Service

- Australian Flying Corps

- Union Defence Force

- South African Aviation Corps

- List of aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps

- List of Royal Air Force aircraft squadrons

- British unmanned aerial vehicles of World War I

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |