Hugh Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Viscount Trenchard

|

|

|---|---|

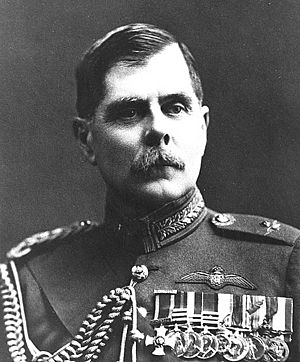

Trenchard in RAF full dress c. 1930

|

|

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | 3 February 1873 Taunton, England |

| Died | 10 February 1956 (aged 83) London, England |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1893–1930 |

| Rank | Marshal of the Royal Air Force |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

| Other work |

|

| Signature | |

Hugh Montague Trenchard (1873–1956) was a very important British officer. He helped create the Royal Air Force (RAF). Because of his efforts, he is often called the "Father of the Royal Air Force."

As a young man, Hugh struggled with school. He barely passed the tests to join the British Army. He served in India and then volunteered for the Boer War in South Africa. During the war, he was badly hurt. He lost a lung and was partly unable to move his legs.

He went to Switzerland to get better. There, he tried bobsleighing. After a bad crash, he found he could walk again! He then returned to active duty in South Africa. After the Boer War, he served in Nigeria, helping to bring peace to the area.

In 1912, Trenchard learned to fly. He quickly became a leader in the early flying forces. During the First World War, he commanded the Royal Flying Corps in France. In 1918, he became the first Chief of the Air Staff. He spent the next ten years making sure the RAF would survive and grow. Later, in the 1930s, he was the head of the Metropolitan Police in London. He is remembered as one of the first people to believe in strategic bombing, which means using planes to bomb important enemy targets far away.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Hugh Montague Trenchard was born in Taunton, England, on February 3, 1873. He was the second son of Henry Montague Trenchard and Georgiana Louisa Catherine Tower Skene. His father was a former army captain. His mother's father was a Royal Navy captain.

When Hugh was two, his family moved to a manor house called Courtlands. It was near Taunton. He loved being outdoors, hunting small animals with a rifle he got at age eight. He and his siblings were taught at home by a tutor. Hugh didn't like his tutor and didn't do well in school. But he loved sports, especially riding.

At age 10, he went to a boarding school in Botley, Hampshire. He was good at arithmetic but struggled with other subjects. His parents weren't too worried, thinking he would have a military career. His mother wanted him to join the Royal Navy, like her father.

In 1884, he moved to Dover to attend a special school. This school prepared students for the Navy's college, HMS Britannia. He failed the Navy entrance exams. At 13, he went to another special school in Wargrave, Berkshire. This school prepared students for Army careers. Again, Hugh didn't focus on his studies. He preferred playing rugby and playing practical jokes.

In 1889, when he was 16, his father went bankrupt. Hugh had to leave school but returned thanks to his relatives. He failed the Woolwich exams twice. He then tried for the Militia, which had easier entry tests. Even these were hard for him, and he failed in 1891 and 1892. Finally, in March 1893, he barely passed. At 20, he became a second-lieutenant in the Royal Scots Fusiliers and was sent to India.

Early Military Career

Serving in India

Trenchard arrived in Sialkot, Punjab, India, in late 1893. He joined his regiment there. Soon after, he had to give a speech at a dinner. Young officers usually talked about the regiment's history. But Hugh simply said he was proud to belong to the regiment and hoped to command it one day. Everyone laughed, but some admired his courage.

Young officers in India in the 1890s had a lot of free time for sports. Trenchard didn't do much military work. He played sports and won the All-India Rifle Championship in 1894. He then started a polo team for his infantry regiment, which was unusual. Within six months, they were competing well.

During a polo match in 1896, he first met Winston Churchill. They clashed on the field. Hugh's sports skills helped his reputation. But he was quiet and didn't fit in socially. People nicknamed him "the camel" because he didn't drink or talk much.

He started reading a lot during this time. He especially liked biographies of British heroes. This reading helped him learn what school hadn't taught him. Militarily, he was unhappy because he didn't see any action. He missed his regiment's turn at the frontier because he went to England for a hernia operation.

When the Second Boer War started in October 1899, he tried many times to rejoin his old battalion in South Africa. His requests were denied. The Viceroy, Lord Curzon, even banned more officers from going to South Africa. Hugh's chances of fighting looked bad.

However, a few years earlier, he had helped Edmond Elles with a shooting contest. Elles, now a military secretary, owed him a favor. In 1900, Trenchard (now a captain) sent an urgent message to Elles. He asked to rejoin his unit overseas. This bold move worked, and he got orders for South Africa a few weeks later.

Fighting in South Africa

In South Africa, he rejoined the Royal Scots Fusiliers. In July 1900, he was told to create and train a mounted company. The Boers were excellent horsemen, and the British needed more mounted units. Trenchard's polo experience helped him get chosen. His new company included some Australian horsemen known for drinking and gambling.

Trenchard's company was part of the 6th Brigade near Krugersdorp. In September and October 1900, they fought in several small battles. On October 5, the Brigade left Krugersdorp to try and fight the Boers in open land. But they had to go through hilly areas where the Boers used guerrilla tactics.

On October 9, Trenchard's company chased some fleeing Boers for 10 miles. The Boers led them into an ambush. Trenchard saw a farmhouse with smoke. He thought the Boers were eating breakfast. He placed his troops around the building. After watching for half an hour, he led four men down to the farmhouse.

When Trenchard and his patrol came out into the valley, the Boers opened fire. Bullets flew past them. He pushed forward to the farmhouse wall. As he headed for the door, a Boer bullet hit him in the chest. The rest of his company rushed down to fight the Boers up close. Many Boers were killed or captured. Trenchard was badly wounded and taken to Krugersdorp for medical care.

Recovery and Return to Duty

Medical Treatment and Healing

At the hospital in Krugersdorp, Trenchard lost a lot of blood. The bullet had gone through his left lung. Doctors thought he would die. But on the third day, he woke up. After three weeks, he improved and was moved to Johannesburg.

When he tried to get out of bed, he couldn't stand. He realized he was partly unable to move his legs. Doctors thought the bullet had damaged his spine after passing through his lung. He was then moved to Maraisburg to recover.

In December 1900, he returned to England on a hospital ship. He used sticks to walk off the ship, where his worried parents met him. He felt very low, being a wounded soldier with no money. He stayed at a nursing home for wounded officers in Mayfair, run by the Red Cross.

His case caught the attention of Lady Dudley, who supported the nursing home. She arranged for him to see a specialist. The specialist said he needed to spend months in Switzerland for his lung. Hugh couldn't afford it, but Lady Dudley gave him a cheque without asking questions.

On December 30, he arrived in St Moritz, Switzerland. He was bored, so he started bobsleighing, which didn't need much leg movement. He often crashed at first. But after some practice, he stayed on the track. During a big crash from the Cresta Run, his spine somehow fixed itself. He could walk freely right after waking up!

About a week later, he won two bobsleigh cups in 1901. This was amazing for someone who couldn't walk alone just days before. Back in England, he thanked Lady Dudley. Then he worked to return to South Africa. His lung still hurt, and he was breathless. The War Office didn't believe he was fully fit.

He took tennis lessons for several months to strengthen his lung. In summer 1901, he entered two tennis competitions. He reached the semi-finals both times and got good newspaper coverage. He sent the newspaper clippings to the War Office doctors. He argued that his tennis ability proved he was fit for duty. After a medical review, his sick leave was cut short. He returned to South Africa in July 1901.

Back to Africa

Service in South Africa

He arrived in Pretoria, South Africa, in late July 1901. He joined a mounted infantry company. Their duties involved long days on horseback. His old wound still caused a lot of pain and often bled.

Later that year, Kitchener, the Commander-in-Chief, called for him. Trenchard was asked to reorganize a mounted infantry company that had lost its morale. He did this in less than a month. Kitchener then sent him to D'Aar to speed up the training of a new mounted infantry group.

In October 1901, Kitchener sent Trenchard on a secret mission. He was to capture the hidden Boer Government. Trenchard was joined by some loyalist Boers he didn't trust, British non-commissioned officers, and nine guides. After riding all night, they were ambushed the next morning. Trenchard and his men fought back. The ambush party left after Trenchard's group suffered some injuries. Even though the mission failed, he was praised for his efforts.

Trenchard spent the rest of 1901 on patrols. In early 1902, he became the acting commander of the 23rd Mounted Infantry Regiment. In the last months of the war, he led his Regiment into action only once. They responded to Zulu raiders stealing cattle in the Transvaal. After peace was agreed in May 1902, he helped disarm the Boers. He was promoted to brevet major in August 1902.

Leading in Nigeria

After the Boer War, Trenchard applied to serve in the West African Frontier Force. He was made Deputy Commandant of the Southern Nigeria Regiment. He was promised he could lead all regimental expeditions. He arrived in Nigeria in December 1903. He had to go over his commanding officer's head to lead his first expedition.

For the next six years, Trenchard led many expeditions into the interior. He patrolled, surveyed, and mapped a huge area of 10,000 square miles, which later became known as Biafra. He won important victories in occasional fights with the Ibo tribesmen. Many tribesmen who surrendered were given jobs building roads. This helped develop the country as part of the British Empire. From 1904 to 1905, Trenchard was the acting Commandant of the Southern Nigeria Regiment. He received the Distinguished Service Order in 1906. From 1908, he was Commandant with the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel.

Back in England and Ireland

In early 1910, Trenchard became very ill with a liver abscess. He returned home to England but didn't recover quickly. He probably pushed himself too hard. By late summer, he was well enough to take his parents on holiday.

In October 1910, he was posted to Derry, where his regiment was stationed. He was reduced from a temporary lieutenant-colonel to major and became a company commander. He played polo and hunted. He found peacetime army life boring. He tried to reorganize his fellow officers' paperwork, which they didn't like. He also argued with his commanding officer, Colonel Stuart. By February 1912, he was trying to find work with other colonial defense forces, but without success.

Learning to Fly

While in Ireland, Trenchard received a letter from Captain Eustace Loraine. Loraine urged him to learn to fly. They had been friends in Nigeria. Loraine had learned to fly after returning to England. Trenchard convinced his commanding officer to give him three months of paid leave to train as a pilot. He arrived in London on July 6, 1912. He then learned that Captain Loraine had died in a flying accident the day before. Trenchard was 39, just under the maximum age of 40 for military student pilots. So, he didn't delay his plan to become a pilot.

He went to Thomas Sopwith's flying school at Brooklands. He told Sopwith he only had 10 days to get his pilot's certificate. He flew solo on July 31, earning his pilot's certificate (No. 270) on a Henry Farman biplane. The course cost £75 and involved only two and a half weeks of lessons. He had a total of just 64 minutes in the air. His instructor noted that teaching him was "no easy performance." However, Trenchard was a "model pupil." His difficulties were partly because he was partially blind in one eye, a secret he kept.

He arrived at Upavon airfield, where the Central Flying School was based. He was assigned to Arthur Longmore's flight. Bad weather delayed Longmore from testing his new student. Before the weather improved, the School's Commandant, Captain Godfrey Paine, made Trenchard a permanent staff member. Part of Trenchard's new duties included being a school examiner. So, he gave himself a test, took it, marked it, and gave himself his 'wings'.

His flying skills were still not great. Longmore soon found his weaknesses. Over the next few weeks, Trenchard spent many hours improving his flying. After his flying course, he was officially appointed as an instructor. However, he was not a good pilot and didn't do much instructing. Instead, he focused on administrative duties. As a staff member, he organized training and set up procedures for the new air arm. He made sure practical skills like map reading, signaling, and engine mechanics were taught. It was during this time that he got the nickname "Boom," either for his loud voice or his low, rumbling tones.

In September 1912, he acted as an air observer during army exercises. This helped him understand how useful flyers could be working with the British Army. In September 1913, he became Assistant Commandant and was promoted to temporary lieutenant-colonel. Trenchard again met Winston Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty and also learning to fly. Trenchard thought Churchill was not a good pilot.

First World War Service

Leading the Military Wing

When the First World War began, Trenchard was put in charge of the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). This meant he was in charge of the RFC's forces in Britain. He was disappointed to stay in England and asked to rejoin his old regiment in France. But General Sir David Henderson, the head of the RFC, refused.

Trenchard's job was to provide replacement pilots and create new squadrons for service in Europe. He first aimed for 12 squadrons. But others suggested 30, and Lord Kitchener later increased the target to 60. To start, Trenchard took over his old civilian flying school at Brooklands. He used its planes and equipment to set up new training schools.

In early October 1914, Kitchener asked Trenchard to quickly provide a battle-ready squadron. This squadron was to help stop German movements during the Race to the Sea. Just 36 hours later, No. 6 Squadron flew to Belgium. This was the first of many squadrons he would provide.

Later in October, plans were made to reorganize the Flying Corps' command. Henderson offered Trenchard command of the new First Wing. Trenchard accepted, but only if he wasn't under Sykes, whom he didn't trust. The next month, the Military Wing was ended. Its units in the UK became the Administrative Wing, led by Lieutenant Colonel E B Ashmore.

Commander of the First Wing

Trenchard took command of the First Wing in November 1914, setting up headquarters in Merville. He found out that Sykes would replace Henderson as Commander of the RFC in the Field. This made Sykes his direct boss. Trenchard didn't like Sykes, and they had a difficult working relationship. Trenchard complained to Kitchener, threatening to resign. His discomfort ended when Kitchener ordered Henderson to return as commander of the RFC in the Field in December 1914.

The RFC's First Wing included Two and Three Squadrons. They supported the British Army's IV Corps and Indian Corps. When the First Army formed in December 1914, the First Wing supported its operations.

In January 1915, General Haig asked Trenchard what could be done in the air war. Haig shared his plans for a March attack in the Merville/Neuve Chapelle area. After aerial photos were taken, the British plans were changed in February. During the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March, the RFC, especially the First Wing, supported the attack. This was the first time planes were used as bombers with missiles attached, not just dropped by hand. However, the bombing had little effect, and the Royal Artillery ignored the airmen's information.

Before British attacks at Ypres and Aubers Ridge in April and May, the First Wing flew reconnaissance missions. They used aerial cameras over German lines. Despite the detailed information and better air-artillery teamwork, the attacks were not decisive. Henderson offered Trenchard the position of his chief of staff. He refused, saying he wasn't suitable, though he likely wanted command. He was promoted to full colonel in June 1915.

Leading the Royal Flying Corps

When Henderson returned to the War Office in summer 1915, Trenchard was promoted to brigadier-general. He was put in charge of the RFC's units in France. He led the RFC in the field until early 1918. In December 1915, Douglas Haig became Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force. Haig and Trenchard worked together again, now at a higher level. In March 1916, as the RFC grew, Trenchard was promoted to major-general.

Trenchard's time leading the RFC on the Western Front had three main goals. First, he focused on supporting and working with ground forces. This included scouting and helping artillery. Later, it involved low-level bombing of enemy targets on the ground. He didn't oppose bombing Germany far away, but he thought supporting ground troops was more important.

Second, he stressed the importance of morale. This meant keeping his own airmen's spirits high. It also meant showing planes to lower the enemy's morale. Finally, he strongly believed in attacking. Many British commanders believed this during the war. But the RFC's constant attacks led to many losses of air crews and planes. Some people questioned if this strategy was worth it.

After German planes bombed London in summer 1917, the government thought about creating an air force. This would combine the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service. Trenchard was against this. He believed it would weaken the air support needed in France. By October, he realized an "Air Force" was coming. He tried to keep control of the flying units on the Western Front. He failed and was replaced in France by Major-General John Salmond.

First Time as Chief of the Air Staff

After the Air Force Bill passed on November 29, 1917, there was a lot of talk about who would get the new top jobs. These included Air Minister and Chief of the Air Staff. Trenchard was called back from France on December 16. That afternoon, he met Lord Rothermere, who had just been made Air Minister.

Rothermere offered Trenchard the Chief of the Air Staff job. Before Trenchard could answer, Rothermere said Trenchard's support would help him attack Sir Douglas Haig and Sir William Robertson in the press. Trenchard refused immediately. He was loyal to Haig and disliked political tricks. Rothermere and his brother, Lord Northcliffe, argued with Trenchard for over 12 hours. They said if Trenchard refused, they would claim Haig refused to release him, to attack Haig. Trenchard defended Haig's constant attacks on the Western Front. He argued it was better than defending, and his own offensive strategy also caused many casualties. Finally, the brothers wore Trenchard down. He accepted the job, but only if he could talk to Haig first. After meeting Haig, Trenchard wrote to Rothermere, accepting the post.

Disagreements and Resignation

In the New Year, Trenchard was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. He became Chief of the Air Staff on the new Air Council on January 18. During his first month, he argued with Rothermere on several points. Rothermere often ignored his professional advice and listened to outside experts. Rothermere also insisted Trenchard claim as many men as possible for the new Royal Air Force, even if they were needed elsewhere. They also disagreed on who should get senior jobs in the RAF.

Most importantly, they disagreed on the future use of air power. Trenchard believed it was key to preventing another stalemate like on the Western Front. Trenchard also resisted pressure from newspapers to support an "air warfare scheme." This plan would have pulled British armies from France and tried to defeat Germany using only the RAF. Despite these differences, Trenchard planned the merger of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service.

However, they grew apart personally. In mid-March, Trenchard found out Rothermere had promised the Navy 4000 aircraft for anti-submarine duties. Trenchard thought air operations on the Western Front were most important. There were fewer than 400 spare aircraft in the UK. On March 18, they exchanged angry letters. The next day, Trenchard sent his resignation. Rothermere asked him to stay, but Trenchard only agreed to delay his departure until April 1, 1918, when the Royal Air Force would officially begin.

After the Germans attacked the British Fifth Army on March 21, 1918, Trenchard ordered all available aircrew, engines, and aircraft to France. On March 26, he received reports that Flying Corps planes were helping stop German advances. On April 5, Trenchard went to France to check on squadrons and understand the air situation. When he returned, he briefed the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and other ministers.

On April 10, Rothermere told Trenchard that his resignation was accepted. Trenchard was offered his old job in France. He refused, saying it would be "damnable" to replace Salmond during a battle. Three days later, Major-General Frederick Sykes replaced him as Chief of the Air Staff. The following Monday, Trenchard was called to Buckingham Palace. King George listened to his story. Trenchard then wrote to the Prime Minister, explaining his side. His letter was shared with the Cabinet, along with an angry reply from Rothermere. Around the same time, Lloyd George was told about Rothermere's general ability as Air Minister. Rothermere realized his situation and resigned, which was announced on April 25, 1918.

Between Duties

After his resignation, Trenchard had no role. He stayed out of the public eye and avoided the press. The new Air Minister, Sir William Weir, needed to find a job for Trenchard. He offered him command of the new Independent Force, which would bomb Germany from long range. Trenchard wanted equal status with Sykes. He argued for a reorganization of the RAF where he would command fighting operations, and Sykes would handle administration. Weir didn't accept this.

Weir offered Trenchard several other options. Trenchard refused a London-based command of bombing operations. He also turned down being Grand Co-ordinator of British and American air policy, and Inspector General of the RAF overseas. Weir then offered him command of all air force units in the Middle East or Inspector-General of the RAF at home. But Weir strongly encouraged him to lead the independent long-range bombing forces in France.

Trenchard had many reasons not to accept these jobs. He saw them as titles with little real power. On May 8, 1918, Trenchard was sitting in Green Park. He overheard a naval officer say, "I don't know why the Government should pander to a man who threw in his hand at the height of a battle, if I'd my way with Trenchard I'd have him shot." After this, Trenchard walked home and wrote to Weir, accepting command of the yet-to-be-formed Independent Force.

Leading the Independent Air Force

After a period of "special duty" in France, Trenchard was appointed General Officer Commanding of the Independent Air Force on June 15, 1918. His headquarters were in Nancy, France. The Independent Air Force continued the work of the VIII Brigade, which it was formed from. It carried out strategic bombing attacks on German railways, airfields, and factories.

At first, the French general Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander, didn't recognize the Independent Air Force. This caused some supply problems. The issues were solved after Trenchard met General de Castelnau, who ignored the concerns and allowed supplies to flow. Trenchard also improved connections between the RAF and the American Air Service. He provided advanced training in bombing to the new American pilots.

In September 1918, Trenchard's Force helped the American Air Service during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. They attacked German airfields, supply depots, and rail lines in that area. Trenchard's close teamwork with the Americans and French became official in late October 1918. His command was renamed the Inter-Allied Independent Air Force and placed directly under Foch. When the armistice came in November 1918, Trenchard asked Foch to return his squadrons to British command, which was granted. Trenchard was replaced by his deputy, Brigadier-General Courtney. Trenchard left France in mid-November 1918 and returned to England for a holiday.

Between the World Wars

Army Mutiny in Southampton

After two months off, Trenchard returned to military duties in mid-January 1919. Sir William Robertson, Commander-in-Chief of Home Forces, asked him to control about 5000 mutinying soldiers at Southampton Docks. They were protesting being sent to France after the war was over.

Trenchard put on his Army general's uniform and arrived at the docks with two staff members. He first tried to talk to the disorderly soldiers, but they heckled and pushed him. He then called for 250 loyal troops. When they arrived, he gave them extra ammunition and ordered them to fix bayonets. He led them to the sheds where the protesting troops were. He threatened to open fire if they didn't immediately return to order. They obeyed.

Chief of the Air Staff (Second Time)

Re-appointment and Illness

In early 1919, Churchill became Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air. Churchill was busy cutting defense spending and demobilizing the Army. The Chief of the Air Staff, Major-General Frederick Sykes, proposed a very large air force for the future, which was unrealistic at the time. Churchill was unhappy with Sykes and thought about bringing Trenchard back. Trenchard's recent handling of the Southampton mutiny had impressed Churchill.

In early February, Trenchard was called to London. At the War Office, Churchill asked him to return as Chief of the Air Staff. Trenchard said he couldn't take the job while Sykes was still in it. Churchill suggested Sykes could be made Controller of Civil Aviation and given a high honor. Trenchard then agreed to think about the offer. Churchill asked Trenchard to write down his ideas for reorganizing the Air Ministry. Trenchard's short statement of what was needed pleased Churchill. Churchill insisted Trenchard take the job. Trenchard returned to the Air Ministry in mid-February and officially became Chief of the Air Staff on March 31, 1919.

For most of March, he couldn't work much because he caught Spanish flu. During this time, he wrote to Katherine Boyle, the widow of his friend James Boyle, whom he knew from Ireland. Mrs. Boyle nursed him back to health. Once he recovered, he asked Katherine to marry him, but she refused. Trenchard stayed in touch with her. When he asked again, she accepted. They married on July 17, 1920, at St. Margaret's Church in Westminster.

Building the RAF and Fighting for its Future

In summer 1919, he worked to finish demobilizing the RAF and set it up for peacetime. This was a huge task, as the force was planned to shrink from 280 squadrons to about 28. During this time, the new RAF officer ranks were decided, despite some opposition from the Army. Trenchard himself was changed from Major-General to Air Vice-Marshal, then promoted to Air Marshal a few days later.

By autumn 1919, budget cuts made it hard for Trenchard to develop the RAF's institutions. He had to argue against the idea that the Army and Navy should provide all support services and education, leaving the RAF only to train pilots. He saw this as a step towards breaking up the RAF. Despite the costs, he wanted the RAF to have its own schools to develop airmanship and the "air spirit." He convinced Churchill, and oversaw the founding of the RAF (Cadet) College at Cranwell. This was the world's first military air academy. In 1920, he started the Aircraft Apprentice system. This program trained highly skilled ground crews for the RAF for the next 70 years. In 1922, the RAF Staff College at Andover was set up to train middle-ranking RAF officers.

In late 1919, Trenchard was made a baronet and given £10,000 for his war service. Although he had some financial security, the RAF's future was not certain. He believed the biggest threat came from the new First Sea Lord, Admiral Beatty. Trenchard met Beatty in early December. He argued that "the air is one and indivisible" and presented a case for an air force with its own strategic role, also controlling army and navy air support. Beatty didn't agree. Trenchard then asked for a 12-month break to put his plans into action. Beatty agreed to let him be until the end of 1920. Trenchard also hinted that some parts of naval aviation might return to the Admiralty. Beatty declined this offer. Later, when no transfer happened, Beatty felt Trenchard had acted unfairly.

In the early 1920s, the RAF's continued independence and its control of naval aviation were reviewed by the government many times. The Balfour Report of 1921, the Geddes Axe of 1922, and the Salisbury Committee of 1923 all supported the RAF's continued existence. This was despite lobbying from the Navy and opposition in Parliament. Each time, Trenchard and his staff, supported by Christopher Bullock, showed that the RAF was cost-effective and needed for Britain's long-term security.

Trenchard also worked to find a war-fighting role for the new Service. In 1920, he successfully argued that the RAF should lead the 1920 conflict in Somaliland. The success of this small air action allowed him to argue for the RAF to police the vast areas of the British Empire from the air. Trenchard especially pushed for the RAF to lead in Iraq at the Cairo Conference of 1921. In 1922, the RAF was given control of all British Forces in Iraq. The RAF also carried out air policing over India's North-West Frontier Province. In early 1920, he even suggested using the RAF to stop "industrial disturbances, or risings" in the UK. Churchill was uneasy about Trenchard's willingness to use deadly force domestically. He told Trenchard not to mention this idea again.

Later Years as Chief of the Air Staff

By late 1924, the creation of the reserve air force, called the Auxiliary Air Force, allowed Trenchard to slightly increase the RAF's strength. Over the next two years, 25 auxiliary squadrons were created. During this time, he introduced the short-service commission scheme. This helped provide regular personnel for the new squadrons. He also started the University Air Squadron scheme. In 1925, the first three U.A.S. squadrons were formed at Cambridge, London, and Oxford.

Since the early 1920s, Trenchard had supported developing a flying bomb. By 1927, a prototype called "Larynx" was successfully tested. However, development costs were high. In 1928, when he asked for more money, the project was stopped. After Britain failed to win the Schneider Trophy in 1925, Trenchard made sure funds were available for an RAF team. The High Speed Flight was formed for the 1927 race. After the British won in 1927, he continued to use Air Ministry funds to support the race. This included buying two Supermarine S.6 aircraft that won the race in 1929. He was criticized by the Treasury for wasting money.

On January 1, 1927, Trenchard was promoted to marshal of the Royal Air Force. He was the first person to hold the RAF's highest rank. The next year, he felt he had done all he could as Chief of the Air Staff. He thought a younger man should take over. He offered his resignation to the Cabinet in late 1928, but it wasn't accepted at first. Around the same time, British and European diplomats in Kabul were cut off by a civil war in Afghanistan. The Foreign Secretary, Austen Chamberlain, asked Trenchard for help. Trenchard assured him the RAF could rescue the stranded civilians. The Kabul Airlift began on Christmas Eve and took nine weeks to rescue about 600 people.

Trenchard remained Chief of the Air Staff until January 1, 1930. Immediately after leaving his post, he was made Baron Trenchard. He entered the House of Lords, becoming the RAF's first peer. Looking back, while he successfully saved the young RAF, his focus on low-cost defense led to a slowdown in the quality of the service's fighting equipment.

Head of the Metropolitan Police

After retiring from the military, he worked as a director for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. He mostly stayed out of public life. However, in March 1931, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald asked him to become Metropolitan Police Commissioner. After initially saying no, he accepted in October 1931. He led the Metropolitan Police until 1935.

During his time, he made several changes. He limited membership in the Police Federation. He introduced fixed terms of employment. He also created separate career paths for lower and higher ranks, similar to the military's officer and non-commissioned system. More people were encouraged to apply, including those with university degrees. Perhaps Trenchard's most famous achievement was setting up the Hendon Police College. This institution trained junior inspectors for higher ranks. He retired in November 1935. In his last months as Commissioner, he received the Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order.

Later Years Before World War II

While he was Metropolitan Police Commissioner, he stayed very interested in military matters. In 1932, he upset the government by sending a private paper. It outlined his ideas for the air defense of Singapore. His ideas were rejected. The Cabinet Secretary, Maurice Hankey, was angry about Trenchard's interference. Later that year, when the government considered a treaty to ban all bomber aircraft, Trenchard wrote to the Cabinet opposing it. The idea was eventually dropped.

Trenchard disliked Hankey. He felt Hankey cared more about agreement among military leaders than fixing defense weaknesses. He started speaking privately against Hankey, who also disliked Trenchard. By 1935, Trenchard secretly pushed for Hankey's removal, believing national security was at risk. After leaving the Metropolitan Police, he could speak publicly. In December 1935, he wrote in The Times that the Committee of Imperial Defence should be led by a politician. Hankey accused Trenchard of "trying to stab him in the back." By 1936, strengthening the Committee of Imperial Defence was a popular topic. Trenchard presented his arguments in the House of Lords. The government agreed, and Sir Thomas Inskip was appointed as the Minister for Coordination of Defence.

With Hankey gone, the Navy again pushed for its own air service. The idea of moving the Fleet Air Arm from Air Ministry to Admiralty control came up. Trenchard opposed this in the Lords, in the press, and in private. But he no longer had the power to stop the transfer, which happened in 1937. Outside of politics, he became Chairman of the United Africa Company. This brought him financial income. The company sought him out because of his knowledge and experience in West Africa. In 1936, he was upgraded from Baron to Viscount Trenchard.

From late 1936 to 1939, he traveled overseas a lot for the companies he worked for. During a visit to Germany in summer 1937, he had dinner with Hermann Göring, the head of Nazi Germany's new Luftwaffe. The evening started friendly but ended in a fight. Göring said, "one day German might will make the whole world tremble." Trenchard replied that Göring "must be off his head." In 1937, Newall became Chief of the Air Staff. Trenchard didn't hesitate to criticize him. As a strong supporter of bombers, Trenchard disagreed with the air expansion program's focus on defensive fighter aircraft. He wrote directly to the Cabinet about it. Trenchard offered his services to the government at least twice, but they were not accepted.

Second World War

Just after the Second World War started, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain asked Trenchard to organize advanced training for RAF pilots in Canada. This might have been a way to get Trenchard out of England. He turned down the job, saying it needed a younger man with up-to-date training knowledge. He then spent the rest of 1939 arguing that the RAF should attack Germany from its bases in France. In 1940, he was offered the job of coordinating camouflage in England, which he flatly refused. Without an official role, he visited RAF units in spring 1940, including those in France, to boost morale. In April, Sir Samuel Hoare, who was again Secretary of State for Air, tried unsuccessfully to get him to come back as Chief of the Air Staff.

In May 1940, after the failure of the Norwegian Campaign, Trenchard used his position in the Lords to criticize the government's weak handling of the war. When Churchill replaced Chamberlain as Prime Minister, Trenchard was asked to organize the defense of aircraft factories. He declined, saying he wasn't interested in helping the general who already had that responsibility. Towards the end of the month, Churchill offered him a job to command all British land, air, and sea forces at home if an invasion happened. Trenchard bluntly replied that to be effective, such an officer would need the military powers of a generalissimo and political power as Deputy Minister of Defence. Churchill was amazed and refused to grant Trenchard such enormous powers, withdrawing the offer.

Despite their disagreement, Trenchard and Churchill remained on good terms. On Churchill's 66th birthday (November 30, 1940), they had lunch at Chequers. The Battle of Britain had recently ended, and Churchill praised Trenchard's pre-war efforts in establishing the RAF. Churchill made Trenchard his last job offer: to reorganize Military Intelligence. Trenchard seriously considered it but declined two days later. He felt the job required a degree of tact that he lacked.

From mid-1940 onwards, Trenchard realized his demanding replies in May had kept him from a key role in the British war effort. He then took it upon himself to act as an unofficial Inspector-General for the RAF. He visited squadrons across Europe and North Africa to boost morale. As a peer and friend of Churchill's, with direct connections to the Air Staff, he championed the Air Force in the House of Lords, in the press, and with the government. He submitted several secret essays on the importance of air power.

He continued to have a lot of influence over the Royal Air Force. Working with Sir John Salmond, he quietly but successfully pushed for the removal of Newall as Chief of the Air Staff and Dowding as the Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command. In the autumn, Newall was replaced by Portal, and Dowding was succeeded by Douglas. Both new commanders were Trenchard's protégés.

During the war, Trenchard's elder stepson, John, was killed in Italy. His younger stepson, Edward, died in a flying accident. His own first-born son, also named Hugh, was killed in North Africa. However, Trenchard's younger son Thomas survived the war.

Later Years and Death

After the war, several American generals, including Henry H. Arnold and Carl Andrew Spaatz, asked Trenchard to brief them. This was for a debate about creating the independent United States Air Force. American air leaders highly respected him and called him the "patron saint of air power." The United States Air Force was formed as a separate branch of the American Armed Forces in 1947.

After the Second World War, Trenchard continued to share his ideas about air power. He also supported creating two memorials. For the first, the Battle of Britain Chapel in Westminster Abbey, he led a committee with Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding to raise funds for the chapel's furnishings and a stained glass window. The second, the Anglo-American Memorial to the airmen of both nations, was put up in St Paul's Cathedral after Trenchard's death. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, he remained involved with the United Africa Company, serving as chairman until he resigned in 1953. He wrote the introduction to the book Haig, Master of the Field (1953). This book defended Douglas Haig's leadership during the First World War, as Haig had been criticized for the high number of British Army casualties. From 1954, for the last two years of his life, Trenchard was partly blind and physically weak.

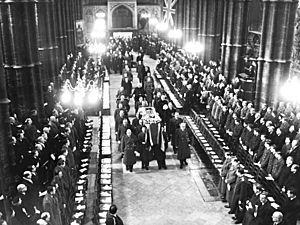

Trenchard died one week after his 83rd birthday, on February 10, 1956, at his London home. His funeral was held at Westminster Abbey on February 21. His body was cremated, and his ashes were placed in the Battle of Britain Chapel. Trenchard's title, Viscountcy, passed to his son Thomas.

Legacy and Recognition

Several places and buildings are named after Hugh Trenchard. These include the University of Ibadan's Trenchard Hall and RAF Cranwell's Trenchard Hall. Also named after him are: Trenchard Lines (part of British Army Headquarters), the small museum at RAF Halton, one of the five houses at Welbeck College, and Trenchard House, used by the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust. In 1977, Trenchard was honored in the International Aerospace Hall of Fame at the San Diego Aerospace Museum.

Trenchard's work in creating the RAF and keeping it independent led to him being called the "Father of the Royal Air Force." He himself didn't like this title, believing General Sir David Henderson deserved it. His obituary in The Times said his greatest gift to the RAF was his belief that air superiority must be gained and kept through attacking. Throughout his life, Trenchard strongly argued that the bomber was the most important weapon for an air force. Today, he is recognized as one of the first supporters of strategic bombing. He also helped shape British policy on controlling the empire using air power.

In 2018, a permanent memorial to him was commissioned as part of the RAF's 100th-anniversary celebrations. It was unveiled in Taunton on June 14 by the 3rd Viscount Trenchard. A road in the town was renamed Trenchard Way at the same time.

Arms

|

|

See also

- List of titles and honours of Hugh Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |