Battle of Carillon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Carillon |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French and Indian War | |||||||

The Victory of Montcalm's Troops at Carillon by Henry Alexander Ogden. Montcalm (centre) and his troops celebrate their victory. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Louis-Joseph de Montcalm Chevalier de Levis |

James Abercrombie George Howe † |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,600 regulars, militia, & Indians | 6,000 regulars 12,000 provincial troops, rangers, & Indians |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 100 killed 500 wounded 150 captured |

1,000 killed 1,500 wounded 100 missing |

||||||

The Battle of Carillon, also known as the 1758 Battle of Ticonderoga, was a major fight during the French and Indian War. This war was part of a bigger global conflict called the Seven Years' War. The battle happened on July 8, 1758, near Fort Carillon (now Fort Ticonderoga) in what is now New York.

In this battle, a smaller French army of about 3,600 soldiers, led by General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, defeated a much larger British force. The British army, with around 18,000 men under General James Abercrombie, attacked the French defenses head-on. They did not use their field artillery (cannons), which was a big mistake. This allowed the French to win a complete victory.

The Battle of Carillon was one of the bloodiest battles in North America during the war. More than 3,000 soldiers were killed or wounded. The French lost about 400 men, while the British lost over 2,000. Many historians see this battle as a classic example of poor military leadership. General Abercrombie ignored good advice and attacked without proper planning. He could have tried to go around the French defenses, waited for his cannons, or surrounded the fort. Instead, he chose a direct attack against a strong French position.

The fort itself was later captured by the British in 1759 and renamed Fort Ticonderoga. This battle made the fort seem unbeatable, which affected later military plans in the area.

Contents

Why was Fort Carillon Important?

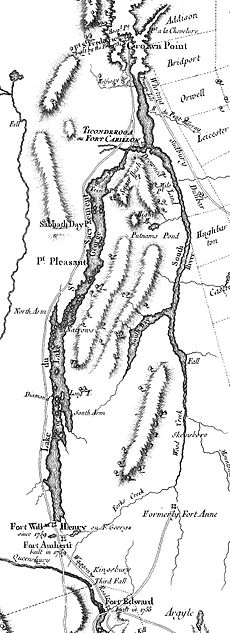

Fort Carillon was built in a very important spot. It sat on a piece of land between Lake Champlain and Lake George. This location was a natural meeting point for armies. French forces could move south from Canada and the St. Lawrence River Valley. British forces could move north from Albany up the Hudson Valley.

East of the fort was Lake Champlain, with Mount Independence on the other side. To the south was the La Chute River, which flowed from Lake George. This river was hard to travel by boat. There was a path, called a portage trail, from Lake George to a sawmill near the fort.

West of the fort was a low hill. But the biggest problem for the fort was Mount Defiance. This 900-foot (270 m) hill was south of the fort, across the La Chute River. It was steep and covered in thick trees. From this hill, cannons could easily fire down into the fort. A French engineer even said he would only need a few cannons to capture the fort from Mount Defiance.

How the War Led to Carillon

Before 1758, the French and Indian War was not going well for the British. They had lost several battles in North America. Because of these losses, William Pitt took full control of Britain's war efforts. He decided to focus on defending Europe and attacking New France (French colonies in North America).

Pitt planned three major attacks in North America. One was to capture Fort Duquesne in Pennsylvania. Another was to take the fortress at Louisbourg. The third attack, led by General James Abercrombie, was aimed at Canada through the Champlain Valley. Abercrombie was not considered a great leader, but he was chosen due to his rank. George Howe, a skilled leader, was made his second-in-command.

The French had started building Fort Carillon in 1755. They used it as a base for their successful siege of Fort William Henry in 1757. However, by 1758, the French situation was difficult. General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, the French commander, knew the British were planning a huge attack. France was not sending much help because the British Royal Navy controlled the Atlantic Ocean. Also, Canada had a poor harvest in 1757, leading to food shortages.

Montcalm and Marquis de Vaudreuil, the governor of New France, disagreed on how to defend. They had fewer than 5,000 regular troops and some militia and Native American allies. The British were expected to have 50,000 men. Vaudreuil wanted to split their forces, but Montcalm thought this was a bad idea. Montcalm believed they should keep their forces together. Vaudreuil's plan was followed, and Montcalm went to Carillon in June 1758.

British Army Gets Ready

The British army, led by General James Abercrombie, gathered near the ruins of Fort William Henry. This fort had been destroyed by the French the year before. Abercrombie's army was huge, with 16,000 men. It was the largest force ever seen in North America at that time.

The army included 6,000 regular British soldiers, like the famous Highlanders. The rest were provincial troops (militia) from colonies like Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York. On July 5, 1758, these troops got into boats and sailed to the north end of Lake George. They landed on July 6.

French Build Defenses

Colonel François-Charles de Bourlamaque was in charge of Fort Carillon before Montcalm arrived. By June 23, he knew a big British attack was coming. He sent out more scouts and learned from captured British soldiers how large the British force was.

Montcalm reached Fort Carillon on June 30. He found only 3,500 men and enough food for just nine days. Scouts reported that the British had 20,000 or more troops. Because of the large enemy force and the fort's weaknesses, Montcalm decided to defend the areas leading to the fort.

He sent Colonel Bourlamaque and three battalions to fortify a river crossing about two miles (3.2 km) from Lake George. Montcalm himself took two battalions to a sawmill closer to the fort. Other troops worked on building more defenses outside the fort. He also asked for reinforcements from Montreal. The Chevalier de Lévis arrived on July 7 with 400 soldiers.

On July 5, when the British fleet was spotted, Montcalm ordered all troops back to Carillon. He also had the bridges on the portage trail destroyed.

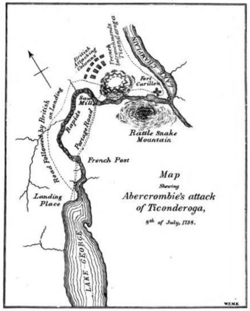

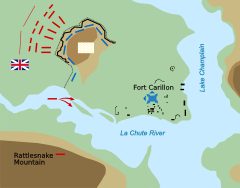

Starting on the evening of July 6, the French began building defenses on a hill northwest of the fort. This hill was about 0.75 miles (1.2 km) away and controlled the land routes to the fort. On July 7, they built a long line of abatis. These were felled trees with sharpened branches pointing outwards, like a giant thorny fence. Above these, they built a wooden breastwork (a low wall). These defenses were built quickly. They could stop musket fire but would not have held up against cannons.

First Skirmish: Bernetz Brook

The British army landed at the north end of Lake George on the morning of July 6 without any resistance. Abercrombie's troops tried to march through the thick woods along the west side of the stream connecting Lake George to Lake Champlain. It was very difficult to move in the dense forest.

Near Bernetz Brook, a French patrol led by Captain Trépezet, trying to get back to their lines, ran into a British regiment. A fight broke out. General Howe's column was nearby, and he led his men towards the sound of the battle. As they got closer, General Howe was hit by a musket ball and killed instantly. This was a big loss for the British.

About 150 of Trépezet's men were killed, and another 150 were captured. Fifty men, including Trépezet, escaped by swimming across the La Chute River. Trépezet died the next day from his wounds. The British, tired from the boat ride and upset by Howe's death, camped in the woods and returned to their landing point the next morning.

Abercrombie's Plan

On July 7, Abercrombie sent Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet and a large force to rebuild the bridges on the portage path. The main army followed and set up camp. British scouts and prisoners told Abercrombie that Montcalm had 6,000 men and was expecting 3,000 more.

Abercrombie sent his engineer, Lieutenant Matthew Clerk, to check the French defenses. Clerk reported that the French position seemed unfinished and could be "easily forced, even without cannon." He didn't realize the French had hidden much of their work with shrubs and trees. Clerk suggested fortifying Mount Defiance, but Abercrombie decided to attack the next morning. He wanted to strike before the supposed 3,000 French reinforcements arrived. In reality, Lévis arrived that evening with only 400 men.

Abercrombie held a meeting with his officers that night. He only asked if the attack should be in three lines or four. He ignored Clerk's advice to fortify Mount Defiance. His plan was a direct frontal assault.

The Battle Begins

The battle started on the morning of July 8. British light infantry and Rogers' Rangers pushed back the few remaining French scouts. Then, provincial troops from New York and Massachusetts moved forward, followed by three columns of British regular soldiers.

Montcalm had organized his French forces into three main groups and a reserve. He commanded the center, while Lévis commanded the right, and Bourlamaque the left. Each group defended about 100 yards (91 m) of the trenches. Cannons protected the sides of the defenses. The low ground near the river was guarded by militia and marines, who also had abatis.

Abercrombie expected the battle to start at 1 p.m., but some New York regiments began fighting the French defenders around 12:30 p.m. This led to a disorganized British attack. Instead of a planned, coordinated advance, British companies rushed forward one by one. The French were ready. They fired heavily on the British as they advanced. The area with the abatis quickly became a "killing field."

By 2 p.m., it was clear the first attack had failed. Montcalm was active on the battlefield, encouraging his men. Abercrombie, however, stayed far from the front lines. It's unclear why he kept ordering more attacks after the first one failed. He later claimed he trusted Clerk's report that the defenses were weak, but this was clearly wrong.

Around 2 p.m., British boats carrying cannons tried to move down the La Chute River. They came too close to the French lines and the fort's cannons. Fire from the fort sank two boats, and the rest retreated.

Abercrombie sent his reserve troops, the Connecticut and New Jersey provincials, into battle around 2 p.m., but their attack also failed. Abercrombie tried to call his troops back, but many, especially the 42nd and 46th regiments, kept attacking. Around 5 p.m., the 42nd made a desperate push and reached the base of the French wall. Those who managed to climb over the wall were killed with bayonets. One British observer wrote that "Our Forces Fell Exceeding Fast." The fighting continued until nightfall.

Finally, realizing the disaster, Abercrombie ordered his troops to retreat to Lake George. The retreat in the dark woods was panicked and disorganized. By dawn the next morning, the army was rowing back up Lake George. It was a humiliating defeat for the British.

What Happened Next?

Montcalm was worried the British might attack again. He had beer and wine brought to his tired troops. They spent the night working on their defenses, ready for another fight.

News of the battle reached England soon after the news of the British victory at Louisbourg. This defeat dampened the celebrations. The full extent of British victories in 1758, like those at Forts Duquesne and Frontenac, came later. If Carillon had also fallen in 1758, the war might have ended sooner. Instead, Montreal, the last French stronghold, did not surrender until 1760. Fort Carillon was captured and renamed Ticonderoga in 1759 by forces under Jeffery Amherst.

Abercrombie never led another military campaign. He was later recalled to England. The defeat also made it harder for the British to get Native American allies for future operations.

Casualties of the Battle

The Battle of Carillon was the bloodiest of the war. Over 3,000 soldiers were killed or wounded. The French had relatively light losses: 104 killed and 273 wounded in the main battle. Including the skirmish on July 6, the French had about 550 casualties.

General Abercrombie reported 547 killed, 1,356 wounded, and 77 missing for the British. However, French reports suggested the British death toll was higher, possibly around 1,000 killed and 1,500 wounded in the main battle. The skirmish on July 6 cost the British about 100 killed and wounded, including General Howe.

The 42nd Regiment, also known as the Black Watch, suffered greatly. More than 300 of their men were killed, and a similar number were wounded. This was a huge part of the total British casualties. Later in July 1758, King George III honored the 42nd Regiment for its bravery in earlier battles. He made it a "Royal" regiment. However, the king did not know about their heavy losses at Carillon until August.

There is a legend about Major Duncan Campbell of the Black Watch. In 1742, the ghost of his dead brother supposedly appeared to him in a dream. The ghost promised to meet him again at "Ticonderoga," a place Campbell had never heard of. Campbell died from wounds he received during the battle.

Legacy of Carillon

Even though the fort itself was never captured in this battle, Ticonderoga became known as an unbeatable fortress. Later, during the American Revolutionary War, American generals like George Washington believed the fort was very strong. However, in 1777, Fort Ticonderoga was surrendered by the Americans without much of a fight.

The modern flag of Quebec is based on a banner said to have been carried by the victorious French forces at Carillon. This banner, now called the flag of Carillon, is very old. However, some historians believe the story of the flag being at the battle is a legend from the 1800s.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Fort Carillon para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Fort Carillon para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |