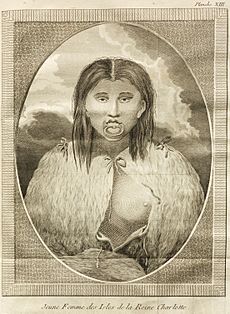

Haida people facts for kids

| X̱aayda, X̱aadas, X̱aad, X̱aat | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN)

|

|

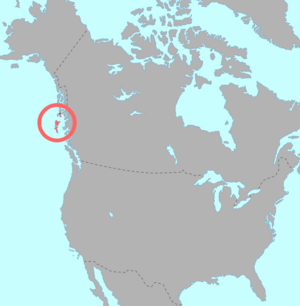

Map of traditional Haida territory

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada | 4,787 |

| United States | 5,977 |

| Languages | |

| Haida, English | |

| Religion | |

| Haida, Christianity | |

The Haida people are an indigenous group who have lived on Haida Gwaii, a group of islands off the coast of British Columbia, Canada, for at least 12,500 years. Some Haida, known as the Kaigani Haida, also live in Southeast Alaska, United States.

The Haida are well-known for their amazing craftsmanship, their skills in trading, and their abilities as sailors. They were also known for their strength and sometimes carried out raids. An early expert on cultures, Diamond Jenness, even compared the Haida to the Vikings because of their strong seafaring traditions.

Today, the Haida government in Haida Gwaii includes different groups like the Hereditary Chiefs Council and the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN). These groups work together to lead the Haida people.

Haida History

Ancient Times

Haida history began thousands of years ago. Their stories say that the first Haida ancestors arrived on Haida Gwaii between 14,000 and 19,000 years ago. These ancestors lived alongside glaciers. They were even there when the first tree, a lodgepole pine, grew on the islands.

For many thousands of years, the Haida took part in a special legal system called Potlatch. About 7,500 years ago, red cedar trees became common on the islands. This changed Haida society. They began to create huge carved cedar monuments and large cedar "big houses."

First Contact with Europeans (18th Century)

The first time Europeans recorded meeting the Haida was in July 1774. A Spanish explorer named Juan José Pérez Hernández sailed near Haida Gwaii. For two days, his ship waited for the currents to calm down so they could land. During this time, several Haida canoes came out to trade with Pérez and his crew. However, the ship could not dock, so they left without stepping onto the islands.

The Haida regularly traded with Russian, Spanish, British, and American fur traders. They were very good at keeping strong trade relationships. In 1787, British Captain George Dixon started trading for sea-otter furs with the Haida. The Haida became central to the profitable China sea-otter trade until the mid-1800s.

Between 1780 and 1830, the Haida sometimes fought with European and American traders. They even captured dozens of ships, like the Eleanor and the Susan Sturgis. They used the weapons they gained, including cannons and small swivel guns on their canoes.

Challenges in the 19th Century

Smallpox Epidemic of 1862

A terrible smallpox epidemic began in March 1862. A ship arrived in Victoria with a passenger who had smallpox. The disease quickly spread to the camps of First Nations people living near the city. Many Haida were among these people.

The government did not vaccinate the First Nations people or quarantine those who were sick. In June 1862, the camps were forced to leave. About 20 canoes of Haida, many likely already infected, were forced back to Haida Gwaii. A gunboat escorted them.

The disease spread quickly through Haida Gwaii, destroying villages and families. The Haida population was about 6,607 before the epidemic. By 1881, it had dropped to only 829 people. Only two villages, Massett and Skidegate, remained. This huge population loss weakened the Haida and made it easier for colonization to happen.

The Potlatch Ban

In 1885, the Haida potlatch (Haida: waahlgahl) was made illegal by the government. The potlatch was a very important system for the Haida's economy and culture. Banning it greatly harmed their financial relationships and cultural traditions. As the islands became Christianized, many cultural items like totem poles were destroyed or taken to museums. This made the Haida feel less connected to their own history and traditions.

20th Century Changes

The Canadian government began sending some Haida children to residential schools as early as 1911. These schools were often far away, and children were forced to speak English and adopt the dominant culture.

Lyell Island Protests

In November 1985, members of the Haida Nation protested against logging old-growth forests on Haida Gwaii. They set up a blockade to stop logging on Lyell Island. This led to a two-week standoff with police and loggers. Seventy-two Haida people were arrested. Pictures of elders being arrested spread widely, bringing attention and support for the Haida across Canada.

In 1987, the Canadian and British Columbia governments signed an agreement. This created the Gwaii Haanas National Park. It is now managed together by the Canadian government and the Haida Nation.

21st Century and Beyond

In December 2009, the government of British Columbia officially renamed the islands from Queen Charlotte Island to Haida Gwaii. The Haida Nation believes they have rights over all of Haida Gwaii. They are working with the provincial and federal governments to discuss these rights.

Haida leaders continue to make laws and manage activities on Haida Gwaii. This includes making agreements with the Canadian communities on the islands. The Haida focus a lot on protecting the land, water, and healthy ecosystems. Almost 70% of the million-hectare islands are now protected. This protection covers the land, water, and smaller culturally important areas. They have also reduced large industrial activities and carefully control access to resources.

Haida Culture

Language

The Haida language is considered a "language isolate." This means it is not closely related to any other known language. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Haida language was almost banned. This happened because of residential schools that forced children to speak English.

Since the 1970s, there have been projects to bring the Haida language back to life. However, only about 30 to 40 Haida-speaking people remain today. Most of them are 70 years old or older.

Potlatch

The Haida hold special ceremonies called Potlatches. These events are important for their economy and social life. During a Potlatch, people gain special things like names and share property through gifts. They are often held to celebrate important events, such as deaths, marriages, or other community gatherings. The most important Potlatches can take years to plan and last for several days.

Art

Haida society continues to create beautiful and unique art. This art is a major part of Northwest Coast art. Haida artists often express themselves through large wooden carvings, like totem poles, Chilkat weaving, or fancy jewelry. In recent times, younger artists are also creating art in new ways, such as Haida manga.

The Haida also created "notions of wealth," which were special items that showed a family's importance. Experts believe the Haida introduced the totem pole (Haida: ǥyaagang) and the bentwood box. Missionaries once thought carved poles were idols, but they actually showed family histories and connected Haida society. Important families put totems outside their homes or as parts of their houses.

Some famous modern Haida artists include Bill Reid, Robert Davidson, Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, and Freda Diesing.

Transformation Masks

Transformation masks were worn during special ceremonies. Dancers used them to show the connection between different spirits. These masks usually showed an animal changing into another animal or a mythical being. The masks represented the souls of the mask owner's family waiting to be reborn.

Masks used in dances had strings that could open them. This would reveal a carving of an ancestor underneath. This showed the idea of change and rebirth. When potlatches were banned in 1885, many masks were taken away. Masks and other items are considered sacred and meant only for certain people to see. Because the masks were taken, it is unknown if the masks in museums are truly meant to be seen. Some believe their display is a result of European colonization.

Film

In 2018, the first full-length Haida-language film, The Edge of the Knife (Haida: SG̲aawaay Ḵʹuuna), was released. It had an all-Haida cast. The actors learned Haida for their roles, with a two-week training camp and lessons during filming. Haida artist Gwaai Edenshaw and filmmaker Helen Haig-Brown directed the movie.

Christopher Auchter, a Haida filmmaker, has also created several Haida-focused films. In 2017, he directed the animated film "The Mountain of SGaana," inspired by Haida stories. In 2020, his documentary "Now Is the Time" was shown at the Sundance Film Festival.

Haida Manga

A unique type of graphic novel has been created by Haida artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas. He calls his graphic novels "Haida manga." This is because he combines traditional Haida art with the style of Japanese manga. Yahgulanaas has published several Haida manga books. Some of these were first created as large wall murals.

Social Organization

Moieties

The Haida people were divided into two main groups called "moieties": the Raven and the Eagle. People from the same moiety were not allowed to marry each other. When a couple married, their children would officially become part of the mother's moiety.

Each moiety had rights to many resources, like fishing spots, hunting areas, and places to build homes. They also had their own myths, legends, dances, songs, and music. Being an Eagle or a Raven was very important to Haida families. It showed which side of the village they would live on and defined their land, history, and customs.

By the late 1800s, the Haida social system began to change. Most Haida families became "nuclear families" (parents and children). At this point, members of the same moiety were allowed to marry each other.

Gender Roles

In traditional Haida families, men and women had different roles. Men were responsible for hunting and fishing. They also built homes and carved canoes and totem poles. Women's jobs were mostly done closer to home. They took care of the house and cured cedarwood for weaving and making clothes. Women also gathered berries and dug for shellfish and clams.

When a boy reached puberty, his uncles on his mother's side would teach him about his family history. They also taught him how to act as a man. It was believed that a special diet could increase his abilities. For example, duck tongues were thought to help him hold his breath underwater. Blue jay tongues were believed to help him be a strong climber.

When a young Haida woman reached puberty, her aunts on her father's side would teach her about her duties to her tribe. The young woman would go to a private space in her family home. They believed that sleeping on a stone pillow and eating and drinking only small amounts would make her tougher.

In the past, young boys and girls entering puberty would go on "vision quests." They would travel alone through the forests for days. They hoped to find a spirit guide for their lives. It was believed that boys and girls destined for greatness could find unique spirit guides. A successful vision quest was celebrated by wearing masks, face paints, and costumes.

Religion

Many Haida people believe in a powerful being called Ne-kilst-lass. This being can appear through the form of a Raven. Ne-kilst-lass created the world and played an active role in bringing life into existence. While Ne-kilst-lass is often kind, it also has a playful and sometimes mischievous side.

Warfare and Protection

Before Europeans arrived, other Indigenous communities saw the Haida as strong warriors. They often tried to avoid sea battles with them. Evidence from old sites shows that Northwest Coast tribes, including the Haida, fought battles as early as 10,000 BC. The Haida preferred sea battles, but they also fought hand-to-hand or with long-range weapons. Sometimes, conflicts were not violent but followed certain rituals. Some even ended in peace treaties that lasted for hundreds of years.

Reasons for Warfare

The Haida fought for several reasons. Many stories say they went to battle mostly for revenge or to capture people as slaves. According to expert Margaret B. Blackman, revenge was a main reason for fighting on Haida Gwaii. Many Northwest Coast legends tell of Haida communities raiding and fighting neighbors because of insults. Other reasons included disagreements over property, land, resources, trade routes, and even women. Often, a battle had many causes, sometimes from disputes that had lasted for decades.

The Haida, like many Northwest Coast Indigenous communities, engaged in slave-raiding. Slaves were highly valued for their labor, and also as bodyguards and warriors. In the 1800s, the Haida fought with other Indigenous communities to control the fur trade with European merchants. Haida groups also had long-lasting feuds with these European merchants.

War Parties and Weapons

A missionary named William Collison once saw a Haida fleet of about forty canoes. The leader of a Haida war party was usually the chief. Medicine men often joined raids to help ensure victory.

The Haida used the bow and arrow until they got firearms from Europeans in the 1800s. However, they still preferred their traditional weapons. Many Haida weapons had more than one use. For example, daggers were very common for close combat. They were also used for hunting and making other tools. Many daggers had their own unique histories.

Battle Armor

The Haida wore rod-and-slat armor. This armor had pieces for the thighs and lower back. It also had flexible slats on the sides for easier movement. They wore elk hide tunics under their armor and wooden helmets. Arrows could not get through this armor. Russian explorers found that bullets could only get through it if shot from very close range. The Haida rarely used shields because their armor was so good.

Haida Villages

Some historical Haida villages include:

- Kiusta

- Kung

- Yan

- Hiellan

- Skidegate (Graham Island)

- Cha'atl

- Haina

- Kaisun (Haida: Ḵaysuun Llnagaay)

- Cumshewa (Moresby Island)

- Skedans (also known as Koona or Q'una)

- Tanu (Louise Island)

- Ninstints (Sgang Gway, also known as Anthony Island)

- Masset (includes Atewaas, Jaahguhl, and Kayung)

- Hlk'yah GaawGa (Windy Bay) (Lyell Island)

- Klinkwan (Prince of Wales Island)

- Sukkwan (Prince of Wales Island)

- Howkan (Prince of Wales Island)

- Kasaan (Prince of Wales Island)

- Tlell, British Columbia

- Dadens, Langara Island

Notable Haida People

- Primrose Adams, artist

- Delores Churchill, artist and basket weaver

- Marcia Crosby, art historian

- Cumshewa, chief

- Florence Davidson, artist and memoirist

- Reg Davidson, carver

- Robert Davidson, carver

- Freda Diesing, carver

- Charles Edenshaw, carver, jeweler, and painter

- Gidansda Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw), artist and politician

- Dorothy Grant, artist and fashion designer

- Jim Hart, hereditary chief and artist

- Koyah, chief

- Gerry Marks, artist

- Bill Reid, carver, sculptor, and jeweler

- Jay Simeon, artist

- Skaay, historian and storyteller

- Evelyn Vanderhoop, weaver

- Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, artist

- Don Yeomans, artist

- Kiefer Collison, placed fourth on season 9 of Big Brother Canada

See also

In Spanish: Haida para niños

In Spanish: Haida para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |