Potlatch facts for kids

A potlatch is a special gift-giving celebration. It is practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in Canada and the United States. For these groups, it was traditionally their main way of governing, making laws, and sharing wealth. This includes groups like the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Coast Salish cultures. Potlatches are also common among peoples living inland and in the Subarctic areas nearby. However, their potlatches are usually less fancy than those of the coastal peoples.

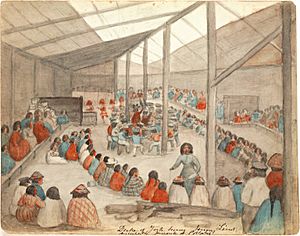

During a potlatch, hosts give away or sometimes destroy valuable items. This shows how wealthy and powerful a leader is. Potlatches also help to strengthen family, clan, and community ties. They also connect people with the spirit world. Important events like naming ceremonies, business deals, marriages, divorces, and funerals can happen at a potlatch. It is also a time to honor ancestors and pass on important knowledge or property. Potlatches help coastal peoples discuss and agree on rights to land and resources. These events often include music, dancing, singing, storytelling, speeches, jokes, and games. Honoring spirits and sharing oral histories are key parts of many potlatches.

Potlatches were once made illegal in Canada by the Government of Canada. But Indigenous nations kept the tradition alive in secret, even though they risked going to jail. Many anthropologists have studied this practice. The potlatch became legal again in 1951. Since then, it has returned in many communities. For some, like the Haida Nation, it is still the foundation of their government.

The word "potlatch" comes from the Chinook Jargon. It means "to give away" or "a gift." It originally came from the Nuu-chah-nulth word paɬaˑč, which means to make a ceremonial gift.

Contents

What is a Potlatch?

This section mainly describes the Kwakwaka'wakw potlatch. Potlatch traditions and customs can be different among other cultures in the region.

A potlatch was held for important events like births, deaths, adoptions, and weddings. They usually took place in the winter. In warmer months, families would gather wealth. Then they would come home and share it with their neighbors and friends. The event was hosted by a numaym, or 'House', in Kwakwaka'wakw culture. A numaym was a large family group. It was usually led by important people, but also included commoners. It had about one hundred members. Several numaym would form a nation.

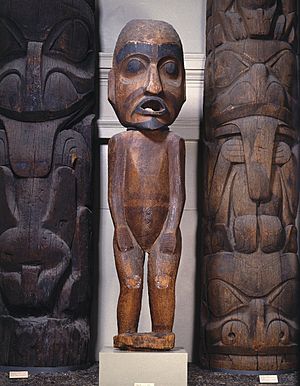

The House got its identity from an ancestor. This ancestor was often a mythical animal who came to earth and became human. The animal mask became a family treasure. It was passed down from father to son, along with the ancestor's name. This made the son the leader of the numaym. He was seen as the living version of the founder.

Only wealthy people could host a potlatch. Slaves were not allowed to be hosts or guests. Sometimes, more than one person from the same family could host a potlatch together. If someone had been shamed, hosting a potlatch could help them regain their good name.

Titles and Gifts

At a potlatch, new leaders would receive special titles. These titles were linked to masks and other important objects. There were two main kinds of titles. First, each numaym had many ranked "seats." These seats gave them a place of honor at potlatches. These titles also gave rights to hunting, fishing, and berry-picking areas. Second, some titles were passed between different numaym, often to family members through marriage. These included feast names that gave a person a role in the Winter Ceremonial.

People could have several "seats." This allowed them to sit in order of their rank. The host would show and give away wealth and make speeches. Besides titles, other valuable items were given away. These included Chilkat blankets, animal skins, and later, Hudson Bay blankets. Ornamental "coppers" were also important gifts. These were shield-like pieces of beaten copper. They were about two feet long and wider at the top. They had a cross shape and a face on the top half. The giving away of many Hudson Bay blankets and the destruction of valuable coppers first caught the attention of the government.

Sometimes, preserved food called sta-bigs was also given as a gift. This food was wrapped in a mat or put in a storage basket.

Showing Status

The host of a potlatch would challenge a guest chief to show even more power. This was done by giving away or destroying more goods. If the guest did not give back more than they received and destroy even more wealth, they and their people would lose respect. This would lessen their "power." The status of families was raised not by having the most resources, but by giving away the most. Hosts showed their wealth and importance by giving away many goods.

Potlatch ceremonies were also used for coming-of-age rituals. When children were born, they received their first name. About a year later, their family would hold a potlatch. They would give gifts to guests on behalf of the child. During this potlatch, the child would receive their second name. When a child reached about 12 years old, they were expected to host their own potlatch. They would give out small gifts they had collected to their family and community. At this point, they would receive their third name.

For some cultures, like the Kwakwaka'wakw, fancy dances are performed. These dances show the hosts' family history and cultural richness. Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret groups. They might show a family's origin from supernatural creatures like the dzunukwa.

Chief O'wax̱a̱laga̱lis of the Kwagu'ł people famously described the potlatch to anthropologist Franz Boas:

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, 'Do as the Indian does'? No, we do not. Why, then, will you ask us, 'Do as the white man does'? It is a strict law that bids us to dance. It is a strict law that bids us to distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you are come to forbid us to dance, begone; if not, you will be welcome to us.

It is important to remember that each Indigenous group has its own unique way of practicing the potlatch. For example, the Tlingit and Kwakiutl nations held potlatch ceremonies for different reasons. Tlingit potlatches were for passing on tribal titles or land, and for funerals. Kwakiutl potlatches were for marriages and welcoming new members into the nation. The word "potlatch" is a general term. Some cultures have many words for different types of gatherings. Most of our detailed knowledge about the potlatch comes from the Kwakwaka'wakw. This was around Fort Rupert on Vancouver Island between 1849 and 1925. This was a time of big social change due to British colonialism.

History of the Potlatch

Before Europeans arrived, gifts included food that could be stored. This included oolichan (candlefish) oil or dried food. Other gifts were canoes, and ornamental "coppers" among important families. Coppers were sheets of beaten copper, shaped like shields. They were about two feet long. They were wider at the top and had a cross shape and a face on the upper half. The copper used was never from Indigenous metal. A copper was considered as valuable as a slave. Only individual wealthy people owned them, not whole family groups. So, coppers could be traded between groups. Many coppers began to be made after Vancouver Island was colonized in 1849. This was when war and slavery ended.

When Europeans arrived, they brought many diseases. Indigenous peoples had no protection against these diseases. This led to a huge drop in population. There were a fixed number of potlatch titles. So, competition for these titles grew. Commoners started to claim titles they couldn't have before. They would hold their own potlatches to make their claims valid. Important families increased the size of their gifts to keep their titles and their social standing. This led to a huge increase in gift-giving. This was possible because many factory-made trade goods became available in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

The Potlatch Ban

Potlatching was made illegal in Canada in 1884. This was added to the Indian Act. Missionaries and government agents strongly pushed for this ban. They thought the potlatch was a "useless custom." They saw it as wasteful and against the 'civilized values' of saving wealth. The government wanted to make Indigenous people adopt European ways of life. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was the biggest problem. He felt it stopped Indigenous people from becoming Christians or "civilized." So, in 1884, the Indian Act was changed to ban the Potlatch. It made practicing it illegal.

In 1888, the anthropologist Franz Boas said the potlatch ban was not working:

The second reason for the discontent among the Indians is a law that was passed, some time ago, forbidding the celebrations of festivals. The so-called potlatch of all these tribes hinders the single families from accumulating wealth. It is the great desire of every chief and even of every man to collect a large amount of property, and then to give a great potlatch, a feast in which all is distributed among his friends, and, if possible, among the neighboring tribes. These feasts are so closely connected with the religious ideas of the natives, and regulate their mode of life to such an extent, that the Christian tribes near Victoria have not given them up. Every present received at a potlatch has to be returned at another potlatch, and a man who would not give his feast in due time would be considered as not paying his debts. Therefore the law is not a good one, and can not be enforced without causing general discontent. Besides, the Government is unable to enforce it. The settlements are so numerous, and the Indian agencies so large, that there is nobody to prevent the Indians doing whatsoever they like.

The potlatch law was later changed to include guests who took part in the ceremony. But there were too many Indigenous people to police, and the law was hard to enforce. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to make the offense easier to prosecute. This meant agents could act as judges, convict, and sentence people. Still, most people thought the law was too harsh and could not be kept. Even the agents who were supposed to enforce it thought it was unnecessary. They believed the potlatch would naturally disappear as younger, educated Indigenous people took over from older ones.

Potlatch Today

The potlatch ban was removed in 1951. Indigenous people now openly hold potlatches. They are committed to bringing back the ways of their ancestors. Potlatches happen often now, and more and more each year. Families are reclaiming their traditions. Anthropologist Sergei Kan was invited by the Tlingit nation to several potlatch ceremonies between 1980 and 1987. He saw some similarities and differences between old and new potlatches. Kan noticed a language gap during the ceremonies. Older members spoke the Tlingit language, but most younger members (under fifty) did not. Kan also noted that modern Tlingit potlatches are no longer required. This means only about 30% of adult tribal members chose to take part in the ceremonies Kan saw. Despite these changes, Kan believed that many important parts and the spirit of the traditional potlatch were still present.

Understanding Potlatch

In his book The Gift, French ethnologist Marcel Mauss used the term potlatch. He used it to describe a whole group of exchange practices in tribal societies. These were called "total prestations." This means they were gift-giving systems with political, religious, family, and economic meanings. The economies of these societies were marked by competitive gift exchange. Givers tried to out-give their rivals. This helped them gain important political, family, and religious roles. Another example of this "potlatch type" of gift economy is the Kula ring found in the Trobriand Islands.

See also

In Spanish: Potlatch para niños

In Spanish: Potlatch para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |