Marcel Mauss facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

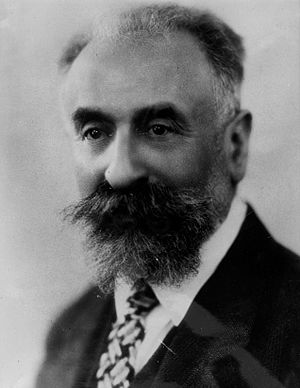

Marcel Mauss

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 10 May 1872 |

| Died | 10 February 1950 (aged 77) Paris, France

|

| Alma mater | Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes |

| Known for | The Gift |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) |

| Influences | Émile Durkheim |

| Influenced |

|

| Signature | |

Marcel Mauss (French: [mos]; May 10, 1872 – February 10, 1950) was an important French sociologist and anthropologist. He is often called the "father of French ethnology," which is the study of different cultures.

Mauss was the nephew of another famous thinker, Émile Durkheim. In his studies, Mauss looked at ideas from both sociology (the study of how societies work) and anthropology (the study of human cultures). He is best known for his ideas on topics like magic, sacrifice, and how people exchange gifts in various cultures around the world. His most famous book is The Gift, published in 1925. Mauss greatly influenced Claude Lévi-Strauss, who started a way of thinking called structural anthropology.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Marcel Mauss was born in Épinal, France, into a Jewish family. His father was a merchant, and his mother owned an embroidery shop. Unlike his younger brother, Marcel did not join the family business. Instead, he became involved in socialist and cooperative movements in his area.

After his grandfather passed away, the Mauss and Durkheim families became very close. This made Mauss think more about his own education. He received a religious education and had a bar mitzvah, but he stopped practicing his religion by age eighteen.

Mauss studied philosophy at Bordeaux University, where his uncle, Émile Durkheim, was teaching. In the 1890s, Mauss began studying many subjects. These included linguistics (the study of language), Indology (the study of India), Sanskrit (an ancient Indian language), Hebrew, and the history of religions and different peoples. He studied these at the École pratique des hautes études. In 1893, he passed a special exam called the agrégation, which allowed him to teach at universities.

Instead of teaching at a high school, Mauss moved to Paris. There, he continued to study comparative religion and Sanskrit.

Career and Political Involvement

Mauss's first published work in 1896 started a long and successful career. He wrote many important books and articles about sociology. Like many other thinkers in the Année Sociologique group, Mauss was interested in socialism. This was a political idea focused on fairness and equality for all people. He especially supported the ideas of Jean Jaurès.

Mauss was very active in the Dreyfus affair, a political scandal involving anti-Jewish feelings in France. He helped edit left-wing newspapers like Le Populaire, L'Humanité, and Le Mouvement socialiste.

In 1901, Mauss started to focus more on ethnography, which is the study of different cultures through direct observation. His work began to show the features we now connect with modern anthropology.

During World War I (1914-1919), Mauss served in the French army as an interpreter. He found military service a break from his intense academic life. However, he also saw the terrible violence of the war. Many of his friends and colleagues died, and his uncle Durkheim passed away shortly before the war ended.

In the early 1920s, Mauss became very interested in politics again. He criticized the Bolsheviks (a political group in Russia) for using force and harming the market economy.

After the war, Mauss helped protect Durkheim's ideas and legacy. He founded research centers like l'Institut Français de Sociologie (1924) and l'Institut d'Ethnologie (1926). These centers encouraged young academics to do fieldwork, which means studying cultures by living among them. He influenced many students who became important anthropologists.

In 1901, Mauss became a professor at the École pratique des hautes études. He taught about the history of religions of non-European peoples. In 1931, he became the first professor of sociology at the Collège de France. He married his secretary in 1934, but she soon became ill. In 1940, Mauss was forced to leave his job and Paris because of the German occupation and anti-Jewish laws. He lived a quiet life after the war and passed away in 1950.

Key Ideas and Theories

Mauss and Emile Durkheim

Marcel Mauss studied under his uncle Durkheim at Bordeaux. They worked together on a book called Primitive Classification. In this book, they explored how different cultures organize their thoughts. They looked at how ideas about space and time are connected to how societies are set up. They studied tribal societies to understand these patterns deeply.

Mauss considered himself a follower of Durkheim's ideas. However, he also developed his own unique way of thinking. Mauss was more involved in politics than his uncle. He was a member of several political groups, including the French workers' party. His political activities continued before and after World War I.

The Gift: A Total Social Fact

Mauss is well-known for his clear and useful way of analyzing social life. His work can be divided into two main areas. First, he studied how exchange works as a system of symbols in different cultures. He also looked at body techniques and the idea of a "person." Second, he focused on how to do social science research.

In his famous book The Gift (1925), Mauss argued that gifts are never truly "free." He showed that throughout human history, giving gifts almost always leads to a return gift. He asked a key question: "What power is in the object given that makes the person who receives it pay it back?"

His answer was that a gift is a "total prestation," or a "total social fact." This means it involves many parts of society at once: legal, economic, religious, and even artistic aspects. A gift is filled with "spiritual mechanisms" and connects the honor of both the giver and the receiver. Mauss believed these exchanges go beyond just material things. They are almost "magical."

The giver doesn't just give an object; they also give a part of themselves. The object is always connected to the giver. Because of this link, giving a gift creates a social bond. The person who receives the gift feels an obligation to give something back. If they don't, they might lose honor and status. In some cultures, like Polynesia, not returning a gift could mean losing mana, which is a spiritual source of power and wealth.

Mauss explained three main obligations in gift-giving:

- Giving: This is the first step to create and keep social relationships.

- Receiving: Refusing a gift means rejecting the social bond.

- Reciprocating: Giving back shows your own generosity, honor, and wealth.

Mauss also discussed how gifts are "inalienable." In a commodity economy (where things are bought and sold), objects are separated from their owners. When you buy something, you fully own it. But in a gift economy, the objects given are not fully separated from the givers. They are more like "loaned" than "sold." The giver's identity is tied to the object. This is why the gift has power and makes the receiver feel they must give back.

Because gifts are inalienable, they must be returned. Giving a gift creates a "gift-debt" that needs to be paid back. This creates a relationship between two people over time. Gift exchange leads to people depending on each other. Mauss believed that a "free" gift that is not returned cannot create social ties. He argued that solidarity (how people stick together in a society) comes from the social bonds made through gift exchange. He stressed that gifts are given to "put people under obligations," even if they seem voluntary.

Mauss and Hubert: Sacrifice and Magic

Mauss also studied sacrifice. In 1899, he wrote Sacrifice and its Function with Henri Hubert. They argued that sacrifice involves making something holy and then unholy. This process directs the holy towards or away from a person or object.

Mauss and Hubert also believed that the human body is not just a natural thing. Instead, it is shaped by specific training, habits, and ways of moving. They called these "body techniques." They said that body techniques are biological, social, and psychological. To understand the body, one must look at all these parts together. They defined a "person" as a way of thinking, connected to laws and morals. They thought a person was made up of different roles, shown through behaviors and body techniques.

In 1902, Mauss and Hubert wrote another book called A General Theory of Magic. They studied magic in early societies and how it affects our thoughts and actions. They argued that only social events can be considered magical. Individual actions are not magic unless the whole community believes in their power.

Legacy and Influence

While Mauss is famous for his own works, especially Essai sur le Don (The Gift), he also did much of his best work with other thinkers from the Année Sociologique group. These included Durkheim (on Primitive Classification) and Henri Hubert (on Outline of a General Theory of Magic and Essay on the Nature and Function of Sacrifice).

Mauss had a big impact on French anthropology and social science. Although he didn't have as many students as some other sociologists, he taught ethnographic methods to the first generation of French anthropology students. His ideas have also greatly influenced later thinkers in anthropology and cultural studies, especially those who combine cultural study with historical, social, and psychological contexts.

Criticisms

Mauss's ideas about gift exchange have faced some criticism. Some critics believe that his essay on "The Gift" tries to apply to all early societies, but it might be better suited for just one society and its relationships.

For example, French anthropologist Alain Testart (1998) argues that there are "free" gifts. He points to people giving money to beggars in a big city. The giver and receiver don't know each other and probably won't meet again. In this case, the donation doesn't create any obligation for the beggar to give back. Testart feels that Mauss might have exaggerated how strong the obligation created by social pressure was, especially in his description of the potlatch among North American Indians.

Another critic, Genevieve Vaughan (1997), who studies gift economy, argues that Mauss's ideas focus too much on gifts always being returned. She believes this hides the simple act of giving and receiving without expecting anything back. She suggests that gift-giving is different from exchange. Vaughan's work explores gift-giving as a relationship that comes from the basic human experience of mothering.

British anthropologist James Laidlaw (2000) gives another example of a non-reciprocal "free" gift. He describes Jain renouncers in India. These are celibate people who live a strict, simple life focused on spiritual purity. They avoid preparing food because it might harm tiny organisms. Since they don't work, they rely on food donations from Jain families. However, the renouncers must not show any wants or desires and only accept food very hesitantly. These "free" gifts challenge Mauss's idea unless the moral and non-material parts of gifting are considered. These non-material aspects are very important to the idea of a gift, as shown in books like Annette Weiner's (1992) Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping While Giving.

Mauss's view on sacrifice was also debated at the time. It differed from how some people thought about individuals and social behavior from a psychological viewpoint. However, Mauss's terms like persona (the roles people play) and habitus (ingrained habits and ways of thinking) have been used in modern sociology. French philosopher Georges Bataille used The Gift to explore new ideas about how money is sometimes wasted in society. Pierre Bourdieu also used Mauss’s concept of habitus to explain how socialization shapes our consciousness and actions, like muscle memory.

Selected Works

- Essai sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice, (with Henri Hubert) 1898.

- La sociologie: objet et méthode, (with Paul Fauconnet) 1901.

- De quelques formes primitives de classification, (with Durkheim) 1902.

- Esquisse d'une théorie générale de la magie, (with Henri Hubert) 1902.

- Essai sur le don, 1925.

- Les techniques du corps, 1934. Marcel Mauss, "Les techniques du corps" (1934) Journal de Psychologie 32 (3–4). Reprinted in Mauss, Sociologie et anthropologie, 1936, Paris: PUF.

- Sociologie et anthropologie, (selected writings) 1950.

- Manuel d'ethnographie. 1967. Editions Payot & Rivages. (Manual of Ethnography 2009. Translated by N. J. Allen. Berghan Books.)

See also

In Spanish: Marcel Mauss para niños

In Spanish: Marcel Mauss para niños