Diamond Jenness facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Diamond Jenness

|

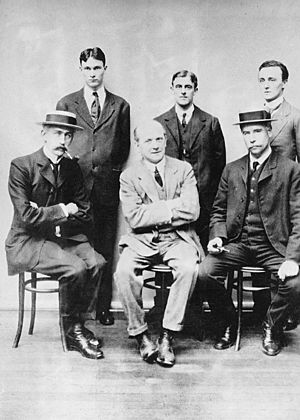

|

|---|---|

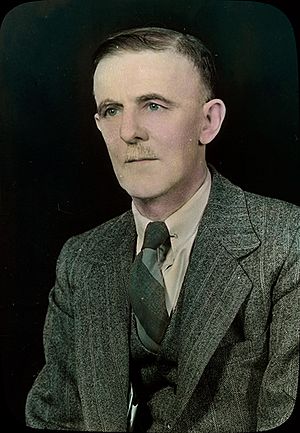

Diamond Jenness, circa 1950

|

|

| Born | February 10, 1886 |

| Died | November 29, 1969 (aged 83) Chelsea, Quebec, Canada

|

| Resting place | Beechwood Cemetery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

| Education | University of New Zealand (from the constituent college in Wellington, then called Victoria University College) Balliol College, University of Oxford |

| Occupation | Anthropologist |

| Employer | National Museum of Canada |

| Known for | His comprehensive early studies of Canada's First Nation's people and the Copper Inuit. |

| Predecessor | Dr. Edward Sapir |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Eilleen Jenness |

| Children | John L. Jenness, Stuart E. Jenness, Robert A. Jenness |

Diamond Jenness (born February 10, 1886, in Wellington, New Zealand; died November 29, 1969, in Chelsea, Quebec, Canada) was a very important early Canadian scientist. He was a pioneer in anthropology, which is the study of human societies and cultures. He helped us understand a lot about Canada's First Nations and Inuit communities.

Contents

Who Was Diamond Jenness?

Diamond Jenness went to the University of New Zealand and then to Oxford University in England. He earned degrees in anthropology, which prepared him for his life's work. From 1911 to 1912, he studied a group of aboriginal people on the D'Entrecasteaux Islands in Papua New Guinea. This was his first experience doing fieldwork.

Working with Indigenous Peoples

Jenness then joined the Canadian Arctic Expedition from 1913 to 1916. He was an ethnologist, meaning he studied different cultures. During this expedition, he focused on the Copper Inuit people near Coronation Gulf. He also studied other Arctic native groups. His detailed work helped him become well-known.

After the expedition, Jenness mostly studied Indian cultures. He also had important administrative jobs. He was the first to identify two very old Eskimo cultures: the Dorset culture in Canada (in 1925) and the Old Bering Sea culture in Alaska (in 1926). Because of this, he is sometimes called the "Father of Eskimo Archaeology." Archaeology is the study of human history through digging up artifacts.

Leading Anthropology in Canada

In 1926, Jenness became the Chief of Anthropology at the National Museum of Canada. He held this position until he retired in 1948. Even though times were tough during the Great Depression and World War II, he worked hard to make the museum's collections and reputation grow. He also wanted to improve how people understood and treated Canada's native peoples. In 1939, he became the president of the American Anthropological Association.

During World War II, Jenness wanted to help. He worked for the Royal Canadian Air Force from 1941 to 1944. He was a civilian Deputy Director of Special Intelligence, which means he helped gather important information. Later, he led a new department that focused on geography for the Canadian government. He retired in April 1948.

His Important Writings

Between 1920 and 1970, Jenness wrote over 100 books and reports about Canada's Inuit and First Nations people. Some of his most famous works include:

- Life of the Copper Eskimos (published 1922): A detailed government report.

- The People of the Twilight (published 1928): A popular book about his two years with the Copper Inuit.

- The Indians of Canada (published 1932): A very important book that is still used today.

- Reports on Eskimo Administration (1962-1968): These looked at how governments managed Inuit affairs in Alaska, Canada, Labrador, and Greenland.

- Dawn in Arctic Alaska (published 1957): A book about his year with the Inupiat of Northern Alaska.

Awards and Recognition

Diamond Jenness received many honors for his work.

- In 1953, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship.

- In 1962, he was given the Massey Medal by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

- In 1968, he became a Companion of the Order of Canada, which is one of Canada's highest honors.

- He also received five honorary doctorate degrees.

- In 1973, the Canadian government recognized him as a Person of National Historic Significance.

- A school in Hay River was named after him.

- In 1978, a peninsula on Victoria Island was named Jenness Peninsula.

- In 2004, a rock on Mars was named after him by the Opportunity rover!

Barnett Richling wrote a full biography about him called In Twilight and in Dawn: A Biography of Diamond Jenness in 2012.

The Canadian Arctic Expedition

In 1913, Diamond Jenness was invited to join the Canadian Arctic Expedition. This trip was funded by the government and led by explorers Vilhjalmur Stefansson and R.M. Anderson. Jenness was one of two ethnologists on the ship.

A Difficult Journey

In June 1913, Jenness boarded the ship Karluk. They sailed towards the Bering Strait and then into the Beaufort Sea. In the fall, the ship got stuck in the ice. It drifted westward and was eventually crushed by the ice near Wrangel Island. Sadly, many crew members died. Jenness was lucky because he had left the ship with a hunting party to find caribou for the crew.

After the Karluk was lost, Jenness and his group traveled to Barrow, Alaska. There, he met up with the other expedition ships. Jenness spent the winter in Harrison Bay, Alaska. He learned to speak the Inuit language and gathered information about Western Inuit customs and stories.

Living with the Copper Inuit

In 1914, Jenness began the main part of his expedition: studying the Copper Inuit of Victoria Island. These people had very little contact with Europeans. Jenness's job was to record their traditional way of life. He was helped by Patsy Klengenberg, who was an interpreter.

Jenness spent two years living with the Copper Inuit. He was adopted by a hunter named Ikpukhuak and his wife Higalik. He hunted and traveled with them, sharing their good times and their struggles. By living so closely with the people he studied, Jenness did something very new for his time. He truly experienced their daily lives.

He wrote about his experience: "I had observed their reactions to every season, the disbanding of the tribes and their reassembling, the migrations from sea to land, fishing to hunting, and then to sealing again. All these changes caused by their economic environment I had seen and studied."

Jenness recorded hundreds of drum dance songs, poems, legends, and stories of "The Copper Inuit of Coronation Gulf." He used wax phonographic cylinders to record sounds. Scholars today say his collection of information is "the most comprehensive description of a single Inuit tribe ever written."

After the expedition, Jenness published many reports and books based on his findings. He also identified ancient Inuit cultures, like the Dorset and Old Bering Sea cultures. These discoveries were very important for understanding how people moved across the Arctic long ago. His ideas about migration were considered "radical" (very new) at the time because there was no Carbon-14 dating to help date artifacts.

Copper Inuit Groups He Studied

Jenness studied several groups of Copper Inuit, including:

- Akuliakattagmiut

- Haneragmiut

- Kogluktogmiut

- Pallirmiut

- Puiplirmiut

- Uallirgmiut (Kanianermiut)

Understanding the Copper Inuit Culture

In one of his articles, Jenness explained how the Copper Inuit were more similar to tribes in the east and southeast than to those in the west. He based this idea on things like archaeological finds, how they built houses, their weapons, tools, art, tattoos, customs, traditions, religion, and even their language. He also looked at how they handled their dead, whether they were covered with stone or wood, or left uncovered.

Jenness also explored whether the use of copper started in one place and then spread, or if different groups discovered it on their own. He believed that Indigenous communities started using copper first, and then the Inuit adopted it. He thought this because Inuit people used slate tools before they started using copper.

He also described the "Copper Eskimos" as being in a "pseudo-metal stage." This means they were somewhere between the Stone Age (when people used stone tools) and the Iron Age (when people used iron tools). The Copper Inuit treated copper like a soft stone, hammering it into tools and weapons instead of melting and shaping it.

Diamond Jenness's work greatly helped us understand how migration patterns affect cultures and how one culture can change into another over time.

See also

In Spanish: Diamond Jenness para niños

In Spanish: Diamond Jenness para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |