Hubert Wilkins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Hubert Wilkins

|

|

|---|---|

Sir Hubert Wilkins (1931)

|

|

| Born | 31 October 1888 |

| Died | 30 November 1958 (aged 70) |

| Known for | Polar explorer |

| Spouse(s) | Suzanne Bennett |

| Awards | Knight Bachelor Military Cross & Bar |

Sir Hubert Wilkins (born October 31, 1888, died November 30, 1958) was an amazing Australian explorer. People often called him Captain Wilkins. He was many things: an explorer of the North and South Poles, a pilot, a soldier, a scientist who studied birds, a geographer, and a photographer.

He won a special medal called the Military Cross for being brave in World War I. He even took charge of American soldiers when their leaders were gone. He's the only Australian war photographer to ever get a medal for fighting.

Wilkins tried to be the first person to travel under the North Pole in a submarine. He didn't quite make it all the way. But he proved that submarines *could* travel under the ice. This helped future explorers succeed. After he passed away, the US Navy took his ashes to the North Pole in a submarine called USS Skate. This happened on March 17, 1959.

Contents

Early Life and Adventures

Hubert Wilkins grew up in Mount Bryan East, South Australia. He was the youngest of 13 children. His family were early settlers and sheep farmers. He was born about 177 kilometers (110 miles) north of Adelaide. He went to school in Mount Bryan East and later in Adelaide.

As a teenager, he worked with a traveling movie theater. He became a cinematographer in Sydney. Then he moved to England. There, he became one of the first people to take photos from an airplane. He worked for Gaumont Studios. His amazing photography skills helped him join several trips to the Arctic. One of these was the 1913 Canadian Arctic Expedition.

Hero in World War I

In 1917, Wilkins returned to Australia. He joined the Australian Flying Corps as a second lieutenant. Later, he became an official war photographer in 1918.

In June 1918, Wilkins earned the Military Cross. He got it for rescuing wounded soldiers during the Third Battle of Ypres. He is still the only Australian official photographer from any war to receive a combat medal. The next month, he became a captain. He led the photography unit for Australian war records.

Wilkins often found himself in the middle of battles. During the Battle of the Hindenburg Line, he took command of American soldiers. Their officers had been lost in an attack. Wilkins led them until help arrived. For this bravery, he received another bar for his Military Cross in 1919.

A famous Australian general, Sir John Monash, once spoke highly of Wilkins. He called him "a highly accomplished and absolutely fearless combat photographer." Monash said Wilkins was wounded many times but always kept going. He rescued wounded soldiers and gathered important information about the enemy. He even led troops in battle.

Exploring the World

After the war, Wilkins continued his adventures. From 1921 to 1922, he worked as a bird scientist (ornithologist). He sailed on the ship Quest to the Southern Ocean.

From 1923 to 1925, Wilkins studied birds in Northern Australia for the British Museum. The museum praised his work. However, Australian officials didn't like his sympathetic views on Indigenous Australians. They also didn't like his criticisms of environmental damage in the country.

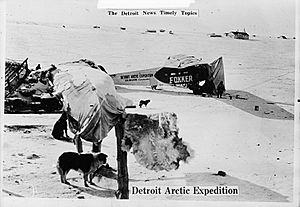

In March 1927, Wilkins and pilot Carl Ben Eielson explored the ice north of Alaska. They landed their airplane on the floating ice. This was the first time a land-plane had landed on drift ice. Wilkins believed aircraft would be very useful for future Arctic explorations.

In December 1928, Wilkins and Eielson made history again. They flew from Deception Island in Antarctica. This was the first successful airplane flight over the continent of Antarctica.

Wilkins received important awards for his work. In 1928, he got the Samuel Finley Breese Morse Medal. He also received the Patron's Medal from the Royal Geographical Society that same year.

On April 15, 1928, Wilkins and Eielson flew across the Arctic. They went from Point Barrow, Alaska, to Spitsbergen. The flight took about 20 hours. For this amazing feat, Wilkins was knighted. This means he became "Sir" Hubert Wilkins. During a celebration in New York, he met an Australian actress, Suzanne Bennett. They later got married.

Wilkins continued his polar flights. He flew over Antarctica in a plane called the San Francisco. He named an island, Hearst Land, after his sponsor, William Randolph Hearst. Hearst thanked Wilkins by giving him and his wife a flight on the famous airship Graf Zeppelin.

The Nautilus Submarine Expedition

Planning the Journey

In 1930, Wilkins and his wife were on vacation with a friend, Lincoln Ellsworth. During this trip, Wilkins and Ellsworth planned an expedition to cross the Arctic in a submarine. Wilkins wanted to study the weather and collect scientific information. He hoped to forecast Arctic weather years in advance. He believed a submarine could carry a full laboratory under the ice.

Many people helped fund the trip. Ellsworth gave $70,000 and loaned $20,000. A newspaper owner, William Randolph Hearst, bought the exclusive story rights for $61,000. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute gave $35,000. Wilkins himself added $25,000 of his own money.

Wilkins leased a submarine that was being retired from the US Navy. It was the O-12. He renamed it Nautilus, after the submarine in Jules Verne's famous book, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. The submarine was specially fitted with a drill. This drill would allow it to bore through the ice above for air. A crew of eighteen skilled men was chosen for the journey.

The Expedition Begins

The expedition faced problems even before leaving New York Harbor. A crew member, Willard Grimmer, fell overboard and drowned.

Wilkins didn't give up. He prepared for test cruises and dives. The crew sailed up the Hudson River to Yonkers. Then they went to New London, Connecticut, for more changes and tests. Wilkins was happy with the submarine and the crew. On June 4, 1931, they left the coast for the North Atlantic.

Soon after starting, the submarine's engines broke down. On June 14, Wilkins had to send an SOS. The USS Wyoming rescued them. The Nautilus was towed to Ireland and then to England for repairs.

By June 28, the Nautilus was fixed and on its way to Norway. They picked up more scientists there. By August 23, they were only 600 miles from the North Pole. But then Wilkins found another big problem. The submarine was missing its diving planes. Without them, he couldn't control the Nautilus when it was underwater.

Wilkins was determined to do what he could. They couldn't explore much under the ice. But the crew did take ice core samples. They also tested the water's saltiness and gravity near the pole.

Wilkins realized the adventure was becoming too dangerous. He received a message from Hearst, begging him to return to safety.

Wilkins ended the first submarine expedition to the poles. He headed for England. But a fierce storm forced them to take shelter in Bergen, Norway. The Nautilus was badly damaged. It couldn't be used anymore. Wilkins got permission from the US Navy to sink the submarine in a Norwegian fjord on November 20, 1931.

Even though he didn't reach his main goal, Wilkins proved something very important. He showed that submarines could operate under the polar ice cap. This paved the way for future successful missions.

Later Life and Legacy

Wilkins became interested in The Urantia Book. He supported the Urantia movement. After the book was published in 1955, he carried it on his travels, even to Antarctica. He told friends it was his religion.

On March 16, 1958, Wilkins appeared on a TV show called What's My Line?

Wilkins passed away in Framingham, Massachusetts, on November 30, 1958. As he wished, the US Navy took his ashes to the North Pole. This happened on March 17, 1959, aboard the submarine USS Skate. The Navy confirmed that his ashes were scattered at the North Pole in a special ceremony.

Many places are named after him in Antarctica. These include the Wilkins Sound, Wilkins Coast, the Wilkins Runway (an airfield), and the Wilkins Ice Shelf. The airport at Jamestown, South Australia, and a road at Adelaide Airport are also named after him. Most of Wilkins' papers and belongings are kept at The Ohio State University Byrd Polar Research Center.

Two animal species are named after him:

- A type of Australian skink (a kind of lizard), Lerista wilkinsi.

- A type of rock wallaby, Petrogale wilkinsi, discovered in 2014.

Wilkins was briefly played by actor John Dease in the 1946 film Smithy.

See also

- Thomas George Lanphier, Sr.