Last voyage of the Karluk facts for kids

The last voyage of the Karluk, a ship used for the Canadian Arctic Expedition from 1913 to 1916, ended sadly. The ship was lost in the Arctic seas, and nearly half of its 25 crew members and staff died. In August 1913, the Karluk, a type of sailing ship called a brigantine that used to be a whaler, got stuck in thick ice. It was on its way to meet other ships at Herschel Island.

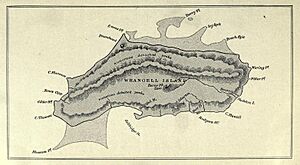

The ship then drifted for a long time across the Beaufort and Chukchi seas. In January 1914, the ice crushed the ship, and it sank. For many months after, the people on board struggled to survive. First, they lived on the ice, and later they reached the shores of Wrangel Island. In total, eleven men died before help finally arrived.

The Canadian Arctic Expedition was led by a Canadian explorer named Vilhjalmur Stefansson. It had goals to study science and explore new areas. Soon after the Karluk got stuck, Stefansson and a small group left the ship. They said they were going to hunt for caribou. But the ice carried the Karluk far to the west, away from the hunting party. Stefansson and his group could not get back to the ship. Stefansson then focused on the expedition's science goals on land. He left the crew and staff on the ship under the command of its captain, Robert Bartlett.

After the ship sank, Captain Bartlett led a difficult march across the ice to Wrangel Island, which was about 80 miles (130 km) away. The journey was very tough and dangerous. Two groups of four men each got lost before the main party reached the island. From Wrangel Island, Bartlett and an Inuk friend named Kataktovik bravely set out across the frozen sea. They were heading for the Siberian coast to find help. Local people helped them, and they eventually reached Alaska. But the sea ice was too bad for an immediate rescue mission.

On Wrangel Island, the stranded group survived by hunting animals. But they did not have enough food and had some disagreements among themselves. Before they were finally rescued in September 1914, three more people died. Two died from illness, and one died in unclear circumstances. In the end, 14 people were rescued.

Historians have different opinions about Stefansson leaving the ship. Some survivors felt he didn't care enough about their suffering and the loss of their friends. He was not officially blamed and was even honored for his later work. Captain Bartlett was criticized by a navy group for taking the Karluk into the ice. But the public and his shipmates saw him as a hero.

Contents

Planning the Arctic Expedition

Why the Expedition Started

The idea for the Canadian Arctic Expedition came from Vilhjalmur Stefansson. He was an anthropologist, a scientist who studies human cultures. Stefansson was born in Canada but lived in the U.S. He had spent many years studying the Inuit people in the Arctic. He learned a lot about the "blond Eskimos" (now known as Copper Inuit).

Stefansson wanted to do another expedition to continue his studies. He got promises of money from the National Geographic Society and the American Museum of Natural History. But he also wanted to explore the Beaufort Sea, which was a blank spot on world maps. For this bigger goal, he needed more money. So, he asked the Canadian government for help.

Canada was worried that an expedition paid for by Americans might give the United States a claim to any new land found. So, in February 1913, the Canadian prime minister, Robert Borden, offered to pay for the whole expedition. Canada hoped the expedition would make its claim to the Arctic islands stronger. The American sponsors agreed to step back, but they said Stefansson had to leave by June 1913. This meant preparations had to be very fast.

Expedition Goals and Plan

The Canadian government's involvement changed the expedition's main focus. It became more about exploring new lands than just scientific studies. Stefansson wrote that the main goal was to explore "a million or so square miles that is represented by white patches on our map." This was the area between Alaska and the North Pole. The expedition also aimed to be the most complete scientific study of the Arctic ever.

The plan was to have two main groups. A Northern Party would search for new lands. A Southern Party, led by zoologist Rudolph Anderson, would study animals, plants, and people on the islands off Canada's northern coast.

The Northern Party's ship, Karluk, would sail north until it found land or was stopped by ice. If it found land, they would explore it. If not, they would follow the ice edge east and try to spend the winter at Banks Island or Prince Patrick Island. If the ship got stuck in the ice and drifted, the party would study ocean currents.

How the Expedition Was Set Up

Stefansson planned to take the expedition to Herschel Island. There, the Northern and Southern Parties would be finalized, and supplies would be divided. Because they had to leave quickly, some members worried about having enough food, clothes, and equipment. Stefansson often wasn't around during these busy weeks and didn't share many of his plans. He dismissed concerns as "impertinent and disloyal."

There were also disagreements between Stefansson and the scientists. The Geological Survey of Canada wanted their scientists to report to them, not to Stefansson. Rudolph Anderson, the Southern Party leader, even threatened to quit.

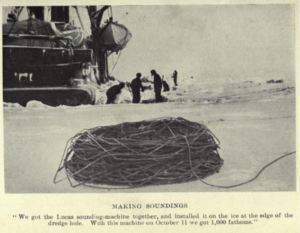

The scientific team included smart people from many countries. But only two had been to the polar regions before. Alistair Mackay, the doctor, had been to Antarctica. James Murray, the oceanographer, was also a veteran. Younger scientists included William Laird McKinlay, a 24-year-old teacher, and Bjarne Mamen, a 20-year-old skiing champion.

Stefansson wanted an experienced whaling captain named Christian Theodore Pedersen to lead the Karluk. When Pedersen couldn't do it, the job went to 36-year-old Robert Bartlett. Bartlett was a skilled Arctic sailor who had commanded Robert Peary's ship on polar trips. However, Bartlett didn't have time to choose the Karluk crew. They were quickly put together from a nearby navy dockyard. McKinlay worried that the crew might not be strong enough for the tough journey ahead. Bartlett shared these worries and even fired his first officer for not being good enough.

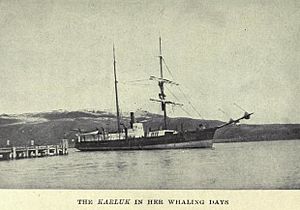

The Ships

Stefansson bought the Karluk for a low price. He was told it was the best ship available for their purpose. But Captain Bartlett had serious doubts about whether it was strong enough for a long trip in the Arctic. The ship was 29 years old and had been built for fishing. It was later changed for whaling. Its front and sides were covered with strong wood. Even though it had made 14 whaling trips to the Arctic, it wasn't built to handle constant ice pressure. It also didn't have a powerful enough engine to push through ice.

The Karluk spent April and May 1913 getting repairs. When Bartlett arrived in June, he ordered even more repairs. Besides the Karluk, Stefansson also bought two smaller ships, the Alaska and the Mary Sachs, to carry supplies for the Southern Party. In the rush to leave, supplies and people were mixed up. Scientists meant for the Southern Party found themselves on the Karluk, while their equipment was on the Alaska. McKinlay, on the Karluk, found most of his equipment on the Alaska. Stefansson promised everything would be sorted out at Herschel Island.

Journey to Herschel Island

The Karluk left Esquimalt, Canada, on June 17, 1913, sailing north towards Alaska. Right away, there were problems with the steering and engines. On July 8, the ship reached Nome, Alaska, where it met the Alaska and Mary Sachs. While loading supplies in Nome, some scientists wanted to meet Stefansson to clarify plans. The meeting didn't go well. Stefansson's attitude upset some, and they thought about leaving. They had read news reports where Stefansson seemed to say he expected the Karluk to be crushed. He also seemed to suggest that the lives of the staff were less important than the scientific work. Stefansson didn't explain these things or give more details about his plans. Despite their worries, no one quit.

At Port Clarence, north of Nome, 28 dogs were brought on board. The Karluk sailed north on July 27. The next day, it crossed the Arctic Circle and immediately hit bad weather. Cabins flooded, and people got seasick. But McKinlay noted that the Karluk was a good ship in rough seas. On July 31, they reached Point Hope, where two Inuit hunters, "Jerry" and "Jimmy," joined.

On August 1, they saw the permanent Arctic ice. Bartlett tried to break through it several times but had to turn back. On August 2, near Point Barrow, the Karluk pushed into the ice but soon got stuck. It drifted slowly east for three days before reaching open water. Stefansson had left the ship to travel over the ice to Point Barrow. He rejoined the ship on August 6, bringing Jack Hadley, an experienced trapper.

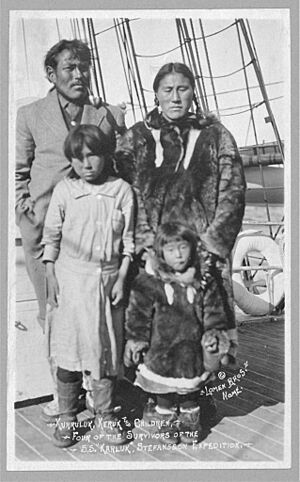

At Cape Smythe, two more Inuit hunters, Keraluk and Kataktovik, joined the expedition. Keraluk's wife, Keruk, and their two young daughters, Helen and Mugpi, also came aboard. As the journey continued, Bartlett worried more about the ice. The ship struggled to move forward. On August 13, Bartlett calculated their position as 235 miles (378 km) east of Point Barrow. This was the farthest east the ship would go. It became firmly stuck in the ice and began to drift slowly westward. By September 10, the Karluk had drifted nearly 100 miles (160 km) back towards Point Barrow. Soon after, Stefansson told Bartlett that they would have to spend the winter stuck in the ice.

Trapped in the Ice

Drifting Westward

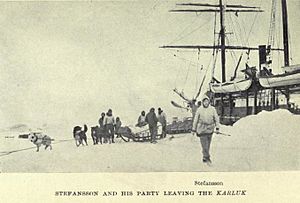

On September 19, with the Karluk stuck, Stefansson announced he would lead a small hunting party. They would look for caribou and other animals near the Colville River. He took two Inuit hunters, his secretary Burt McConnell, photographer George Wilkins, and anthropologist Diamond Jenness. Stefansson expected to be gone for about ten days. He told Bartlett that if the ship moved, he should send a party ashore to leave messages about the ship's location. The six men left the next day.

On September 23, after a snowstorm, the ice floe holding the Karluk began to move. The ship started drifting between 30 and 60 miles (48 and 97 km) a day. But it was moving west, farther and farther from Herschel Island and Stefansson's party. It soon became clear they couldn't get back to the ship.

Some people later suggested that Stefansson had abandoned the ship. However, the expedition's historian, S.E. Jenness, disagrees. He points out that Stefansson and his party left valuable things on board. Another idea is that Stefansson wanted to train the younger staff. Anthropologist Gísli Pálsson says that while the crew's anger is understandable, there's no proof Stefansson purposely left them. Pálsson believes Stefansson was trying to get fresh meat to prevent scurvy, a serious illness. Historian Richard Diubaldo also thinks it was a normal hunting trip.

Heavy snow and thick fog made it hard for Bartlett to know exactly where the Karluk was. On September 30, they briefly saw land, which they thought was Cooper Island near Point Barrow. On October 3, worries grew when the drift turned north, away from land. Some feared the Karluk would end up like the Jeannette, an American ship that sank after drifting for months, with most of its crew lost. Bartlett noticed that Murray and Mackay, the two veterans, were openly critical of his leadership. They were planning to leave the ship on their own.

As the weather worsened, Bartlett ordered supplies and equipment moved onto the ice. This lightened the ship and prepared them in case they had to abandon it quickly. They added to their food by hunting seals and even a polar bear. On November 15, the Karluk reached its farthest north point. Then it began moving southwest, towards the Siberian coast. By mid-December, they were about 140 miles (225 km) from Wrangel Island. Despite the grim outlook, they celebrated Christmas with decorations, presents, and games on the ice. By then, they were only 50 miles (80 km) north of Herald Island. On December 29, they saw land in the distance. This raised spirits, but in the New Year, the ice began to break up. McKinlay wrote that "the twanging, drumming, ominous ice sounds got louder and nearer."

The Ship Sinks

Early on January 10, 1914, McKinlay wrote that "a severe shudder shook the whole ship" as the ice hit the hull. Bartlett, still hoping to save his ship, ordered all snow removed from the decks to lighten it. He also told everyone to get warm clothes ready. At 6:45 p.m., a loud bang meant the hull had been pierced. Bartlett saw water pouring in through a 10-foot (3 m) gash. The pumps couldn't handle it, so the captain ordered everyone to leave the ship.

The weather was terrible, but the crew and staff worked all night in the dark and snow. They moved more food and equipment onto the ice. Bartlett stayed on board until the very last moments. He played loud music on the ship's record player and burned each record when it finished. At 3:15 p.m. on January 11, Bartlett played Chopin's Funeral March as a final goodbye to the ship, then stepped off. The Karluk sank within minutes, its masts breaking as it disappeared into the narrow hole in the ice. McKinlay counted the stranded party: 22 men, one woman, two children, 16 dogs, and a cat.

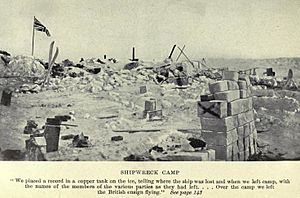

Life at Shipwreck Camp

Bartlett had already put supplies on the ice, so a camp, called "Shipwreck Camp," was mostly ready when the Karluk sank. They built two shelters: one was a snow igloo with a canvas roof, and the other was made from packing cases. They added a kitchen with a stove rescued from the ship. A small, separate shelter was built for the five Inuit. McKinlay said the camp provided "substantial and comfortable houses." They had plenty of food and ate well. In the first days, they spent time preparing clothes and sleeping gear for the march to Wrangel Island. The ice was slowly drifting the camp towards the island, but there wasn't enough daylight yet to start the march.

During this time, Mackay and Murray, joined by anthropologist Henri Beuchat, didn't participate much in camp life. They wanted to leave on their own as soon as possible. Bartlett wanted to wait for more daylight in February before marching. But McKinlay and Mamen convinced him to send a small group ahead to set up a camp on Wrangel Island. A group of four, led by first officer Alexander Anderson, left Shipwreck Camp on January 21. They were told to set up their camp on Wrangel Island's north shore. On February 4, Bjarne Mamen, who went as a scout, returned to Shipwreck Camp. He reported that he had left the group a few miles short of land. It was clearly not Wrangel Island, but probably Herald Island, 38 miles (61 km) from their goal. This was the last time Anderson's party was seen. Their fate was only discovered ten years later when their remains were found on Herald Island.

March to Wrangel Island

Bartlett decided to send a team back to find the exact location of the island Anderson's party had approached. Ship's steward Ernest Chafe, with the Inuit pair Kataktovik and Kuraluk, went on this mission. Chafe's group got within 2 miles (3 km) of Herald Island but were stopped by open water. They saw no signs of the missing party and concluded Anderson's group hadn't reached the island. Chafe and his party then returned to Shipwreck Camp.

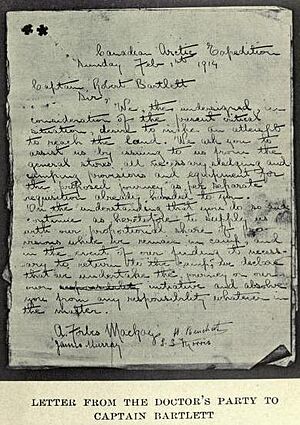

Meanwhile, on February 4, Mackay and his group (Murray, Beuchat, and seaman Stanley Morris) announced they were leaving the next day. Mackay gave Bartlett a letter saying they wanted to try to reach land on their own. They asked for supplies and said Bartlett wasn't responsible for them. Bartlett gave them a sledge, a tent, oil, a rifle, ammunition, and food for 50 days. They left on February 5. Chafe and the Inuit saw them a few days later, struggling. Some of their supplies were lost, and clothes were thrown away to lighten their load. Beuchat was in a very bad state, almost delirious from the cold. But the group refused help and wouldn't return to Shipwreck Camp. Later, a scarf belonging to Morris was found in an ice floe. It was thought the four had either been crushed by ice or fallen through it.

Bartlett's party now included eight Karluk crew members, three scientists, John Hadley, and five Inuit. Hadley, nearly 60, was one of the few with experience traveling on ice. Bartlett sent groups ahead to make a path and set up supply points on the way to Wrangel Island. This prepared his inexperienced party for the difficult ice travel. When he felt they were ready, he divided them into four teams. The first two left on February 19. Bartlett led the last two groups from the camp on February 24. He left a note in a copper drum in case the camp drifted into an inhabited area. Wrangel Island was estimated to be 40 miles (64 km) away, but the journey turned out to be twice as long.

The ice surface was very broken, making travel slow. Storms had destroyed much of the path made by the advance parties. At one point, breaking ice almost destroyed Bartlett's camp while his team slept. On February 28, all parties met in front of huge ice ridges, 25 to 100 feet (7.6 to 30.5 m) high, blocking their way. McKinlay, Hadley, and Chafe went back to Shipwreck Camp for supplies. The others slowly cut a path through the ridges. When McKinlay's group returned a week later, they had only moved forward three miles (5 km), but the worst ridges were behind them. Hadley said the ridges were worse than anything he had seen in his many years in the Arctic. The last part of the journey was easier, over smoother ice. On March 12, they reached land, a long sand spit on the north side of Wrangel Island.

Bartlett's Journey for Help

Bartlett's first plan was for the group to rest on Wrangel Island and then go together to the Siberian coast. But three men were injured, and others were weak from frostbite. So, Bartlett decided the main group should stay on the island while he went for help with only Kataktovik. They left on March 18 with seven dogs and food for 48 days. They took a long route around the island's southern shores to look for signs of Anderson's or Mackay's parties. Finding nothing, they headed across the ice towards Siberia. Progress was slow because the ice was constantly moving and breaking up. Snow also drifted, burying their supplies. As they got closer to the mainland, Kataktovik became nervous. He had heard that Alaskan Inuit were not liked by the native Chukchi people in Siberia. Bartlett tried to calm him as they moved forward.

On April 4, the pair reached land near Cape Jakan on the northern Siberian coast. Sledge marks in the snow showed people lived there. They followed the tracks for a day and arrived at a small Chukchi village. Here, they were welcomed kindly, given shelter and food. On April 7, they set out for East Cape. Bartlett had never experienced such cold weather, with blizzards, strong winds, and temperatures often below -50°C (-58°F). Along the way, they passed through several Chukchi villages. Bartlett traded goods for supplies, even exchanging his revolver for a strong young dog. Bartlett was touched by the kindness of the people they met. On April 24, they arrived at Emma Town. Bartlett calculated that in 37 days, he and Kataktovik had traveled about 700 miles (1,100 km), mostly on foot.

At Emma Town, Bartlett met Baron Kleist, a Russian official. Kleist offered to take him to Emma Harbour, a week's journey away, where he could look for a ship to Alaska. Bartlett accepted. On May 10, still weak from his journey and a throat infection, he said goodbye to Kataktovik and left with the baron. On the way, they learned that Captain Pedersen was in the area. On May 16, they reached Emma Harbour. Five days later, Pedersen arrived in his whaling ship, Herman. He immediately took Bartlett on board and set off for Alaska. They arrived off Nome on May 24, but ice prevented them from reaching shore. After three days, they turned south and landed at St Michael. There, Bartlett finally sent a radio message to Canada, telling them about the Karluk's fate. He also asked about the United States revenue cutter Bear, hoping it could rescue the stranded party.

On Wrangel Island

The group from Shipwreck Camp landed on the north side of Wrangel Island, at a place they called "Icy Spit." Before he left, Bartlett asked the party to set up several camps around the island. This would give them more areas to hunt. He also thought separating into smaller groups would help people get along better. He wanted all groups to meet again at Rodgers Harbor, on the south side of the island, around mid-July.

However, disagreements started almost immediately after Bartlett left, especially about sharing food. They hadn't been able to bring all the supplies from Shipwreck Camp, and the trek had taken longer than expected. So, they were short on biscuits, pemmican (a dried meat and fat mixture), and dog food. There was little chance of hunting birds and game until the weather improved in May or June. When Hadley and the Inuit, Kuraluk, returned from a seal hunt, Hadley was suspected of hiding some of the meat for himself. The same pair were also accused of wasting cooking oil. McKinlay wrote that these problems made everyone sad and destroyed their teamwork.

Two attempts were made to go back to Shipwreck Camp for more food, but both failed. Ernest Chafe's feet got so badly frozen that his toes had to be removed by second engineer Williamson, using makeshift tools. McKinlay and Munro risked their lives by traveling over the sea ice towards Herald Island. They wanted to find the missing parties. They couldn't get closer than 15 miles (24 km) and saw no signs of life through binoculars.

Other health problems continued. Malloch's frostbitten feet didn't heal, and Mamen's knee, which he had dislocated, bothered him constantly. A worrying illness began to affect many people. Symptoms included swelling of the legs and other body parts, along with extreme tiredness. Malloch was the worst affected; he died on May 17. But his tent-mate Mamen was too sick to bury him, so the body lay in the tent for several days, creating a "frightful smell," until McKinlay arrived to help. Mamen himself died ten days later from the same weakening disease.

From early June, birds appeared, providing much-needed food and eggs. As the seal meat ran out, the party was forced to eat rotten flippers, hide, or any edible part of a seal. Sharing birds also caused arguments. Breddy was suspected of stealing. On June 25, after a gunshot was heard, Breddy was found dead in his tent. The cause of his death was unclear. Various items stolen from McKinlay were found among Breddy's belongings.

Despite the difficult situation, the Canadian flag was raised at Rodgers Harbor on July 1 to celebrate Dominion Day. Later that month, spirits improved when Kuraluk caught a 600-pound (270 kg) walrus, providing fresh meat for several days. As August arrived with no sign of a ship and the weather turned cold again, hopes of rescue faded. The party began to prepare for another winter.

Rescue

The rescue ship Bear arrived in St Michael, Alaska, in mid-June. Its captain, Cochran, agreed to go to Wrangel Island as soon as he got permission from the U.S. government. They couldn't try the rescue before mid-July because the ice conditions were very bad that year. After getting permission, the Bear, with Bartlett on board, left St Michael on July 13. The ship had many stops to make along the Alaskan coast before it could go to Wrangel Island. On August 5, at Port Hope, Bartlett met Kataktovik and gave him his expedition wages and new clothes. At Point Barrow on August 21, Bartlett met Burt McConnell, Stefansson's former secretary. McConnell told him what Stefansson had been doing since leaving the Karluk the previous September. In April 1914, Stefansson had gone north with two friends, looking for new lands.

McConnell left Point Barrow for Nome on the King and Winge, an American walrus hunting ship. Meanwhile, the Bear finally sailed for Wrangel Island. On August 25, the Bear was stopped by ice 20 miles (32 km) from the island. After failing to break through, Captain Cochran had to return to Nome for more coal. Back in Nome, Bartlett met Olaf Swenson, who had rented the King and Winge for the season and was about to sail for Siberia. Bartlett asked if the King and Winge could stop by Wrangel Island and look for the stranded Karluk party. The Bear left Nome on September 4, a few days after Swenson's ship.

The King and Winge, with McConnell still aboard, reached Wrangel Island on September 7. That morning, the group at Rodgers Harbor woke up to the sound of a ship's whistle. The King and Winge was a quarter-mile offshore. The survivors were quickly taken to the ship. Then, the ship picked up the rest of the stranded party who were camped along the coast at Waring Point. By the afternoon, all 14 survivors were on board.

After a failed attempt to get close to Herald Island, the ship began the journey back to Alaska. The next day, it met the Bear, with Bartlett on board. McConnell wrote that the party wanted to stay on the ship that had rescued them. But Bartlett ordered them aboard the Bear. Before returning to Alaska, the Bear made one last attempt to reach Herald Island. Ice stopped them 12 miles (19 km away), and they saw no signs of life. The reunited party arrived at Nome on September 13, to a big welcome from the local people.

What Happened Next

Bartlett was celebrated as a hero by the newspapers and public. The Royal Geographical Society honored him for "outstanding bravery." However, a navy group later criticized him for taking the Karluk into the ice. They also blamed him for letting Mackay's party leave the main group, even though Mackay had signed a letter saying Bartlett wasn't responsible. Stefansson also privately criticized Bartlett. Bartlett continued his career at sea, leading many more trips to the Arctic over the next 30 years. He died in April 1946 at age 70. His book about the Karluk disaster, published in 1916, doesn't directly criticize Stefansson. But Niven notes that Bartlett told his friends he thought very poorly of his former leader.

In 1918, Stefansson returned after four years, saying he had discovered three new islands. He was honored by the National Geographical Society and became president of the Explorers Club of New York. In Canada, his reception was less enthusiastic. There were questions about the expedition's high costs, its poor initial organization, and how he managed the Southern Party. Rudolph Anderson and other Southern Party members later asked the Canadian government to investigate statements Stefansson made in his 1921 book The Friendly Arctic. They felt his words made them look bad. The request was denied. In his book, Stefansson took responsibility for the "bold" decision to take Karluk into the ice. However, McKinlay felt the book gave an inaccurate account, "putting the blame... on everyone but Vilhjalmur Stefansson." Historian Tom Henighan believes McKinlay's biggest complaint was that Stefansson "never at any time seemed able to express an appropriate sorrow over his lost men." Stefansson never returned to the Arctic and died in 1962 at age 82.

The fate of First Officer Alexander Anderson's party was unknown until 1924. An American ship landed at Herald Island and found human remains, along with food, clothing, and equipment. From these items, they knew it was Anderson's party. The cause of death was not clear, but since there was plenty of food, starvation was ruled out. One idea was that their tent blew away in a storm, and they froze to death. Another was carbon monoxide poisoning inside the tent.

The strange illness that affected most of the Wrangel Island party and led to the deaths of Malloch and Mamen was later identified as a kidney problem. This was caused by eating bad pemmican. Stefansson explained that "our pemmican makers had failed us through supplying us with a product deficient in fat." Peary, another explorer, had stressed that an Arctic explorer should pay very close attention to how their pemmican was made. McKinlay believed Stefansson spent too much time promoting the expedition and not enough time making sure the food was good.

Many of the Karluk survivors lived long lives. Williamson, who never spoke or wrote about his Arctic experiences, lived to be 97. McKinlay died in 1983 at 95, after publishing his own account in 1976. Kuraluk, Keruk, and their daughters, Helen and Mugpi, returned to their life at Point Barrow. The two girls, Pálsson says, "provided important sources of cheer at the darkest moments." Mugpi, later known as Ruth Makpii Ipalook, was the very last survivor of the Karluk voyage. She died in 2008 at age 97, after a full life.

Published Accounts of the Voyage

Six first-hand accounts of the Karluk's last voyage have been published. Stefansson's account only covers the period from June to September 1913. Expedition secretary Burt McConnell wrote an account of the Wrangel Island rescue, published in The New York Times in 1914. A version of McConnell's story appears in Stefansson's book.

- 1914: Bartlett's story of the Karluk – Robert Bartlett

- 1916: The Last Voyage of the Karluk – Robert Bartlett and Ralph Hale

- 1918: The Voyage of the Karluk, and its Tragic Ending – Ernest Chafe

- 1921: The Friendly Arctic – Vilhjalmur Stefansson

- 1921: The Story of the Karluk – John Hadley

- 1976: Karluk: The great untold story of Arctic exploration – William Laird McKinlay

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |