Thule people facts for kids

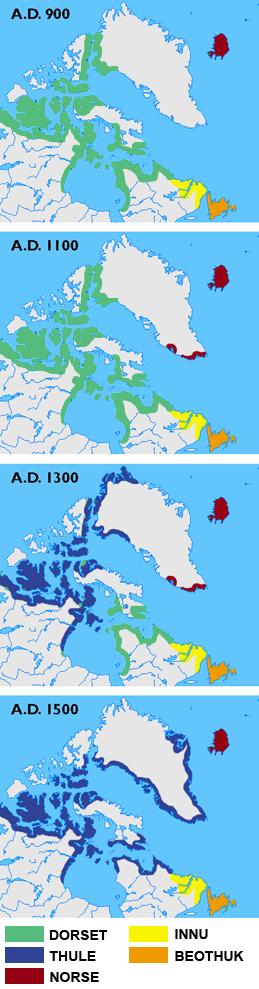

The Thule people were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They started developing in coastal Alaska around the year 1000. From there, they moved eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 1200s. As they spread, they replaced the people of the earlier Dorset culture who lived in those areas. The name "Thule" comes from a place in northwest Greenland where their ancient remains were first found. The Thule people are connected to the Inuit through their genes, way of life, and language.

There is proof that the Thule people, and also the Dorset culture, met the Vikings. The Vikings arrived in Canada in the 1000s. In Viking writings, these people were called the Skrælingjar. Some Thule people moved south in a "Second Expansion." By the 1200s or 1300s, the Thule had taken over areas where the Central Inuit lived. By the 1400s, the Thule had completely replaced the Dorset people. More contact with Europeans began in the 1700s. Along with the tough times of the "Little Ice Age" (1650–1850), the Thule communities started to break apart. From then on, these people became known as the Inuit.

Contents

History of the Thule People

The Thule Tradition lasted from about 200 BC to 1600 AD around the Bering Strait. The Thule people are the ancient ancestors of the Inuit who now live in Northern Labrador. A scientist named Therkel Mathiassen helped map out the Thule culture. He was an archaeologist on a Danish expedition to Arctic America from 1921 to 1924. He dug up sites on Baffin Island and in the northwestern Hudson Bay area. He believed these were the remains of a skilled Eskimo whaling culture. This culture started in Alaska and moved to Arctic Canada about 1000 years ago.

There are three main stages that led to the Thule culture: Okvik/Old Bering Sea, Punuk, and Birnirk. These groups are sometimes called "Neo-Eskimo" cultures. They are different from the older Norton tradition. The Thule Tradition replaced the Dorset Tradition in the Eastern Arctic. The Thule brought kayaks and umiaks (skin-covered boats) to the area. They also found new ways to use iron and copper. They had advanced harpoon technology and were skilled at hunting bowhead whales. Bowhead whales are the largest animals in the Arctic. The Thule culture spread across the coasts of Labrador and Greenland. It is the most recent "neo-Eskimo" culture.

Early Thule Stages: Old Bering Sea, Punuk, and Birnirk

The early stages of the Thule Tradition show how their culture changed over time.

Old Bering Sea Stage (200 BC to 500 AD)

The Old Bering Sea (OBS) stage was first described by Diamond Jenness. He found decorated ivory harpoon heads and other items on St. Lawrence and Diomede Islands. Jenness thought the Bering Sea culture was a very advanced Inuit culture from Asia, existing before the main Thule period.

The Thule people, starting with the OBS stage, were very good at living by the sea. This is clear from the tools they left behind. Kayaks and umiaks (large skin boats) appear in their archaeological record for the first time. Their tools were mostly made of polished slate, not flaked stone. These included knives, spear points, and the ulu (a special knife with a curved blade). They also made simple pottery. They used a lot of bone and antlers for harpoon heads, darts, spears, snow goggles, and shovels.

Many new ideas helped them hunt more effectively. They used harpoons with ice picks for seal hunting. They also had ivory plugs and mouthpieces for inflating harpoon line floats. These floats helped them recover larger sea mammals after they were hunted. These people relied heavily on seals and walruses for food. OBS tools are easy to spot because they had artistic designs. These designs included curved lines, dots, circles, and short lines.

Punuk and Birnirk Stages (800 to 1400 AD)

The Punuk stage developed from the Old Bering Sea stage. It was found on the main Strait islands and along the shores of the Chukchi Peninsula. The Punuk culture was first identified by Henry Collins in 1928. He found items in a deep midden (an ancient trash heap) on one of the Punuk Islands. Later digs on St. Lawrence Island showed a continuous cultural change from Old Bering Sea to Punuk, and then to modern Eskimo culture.

Punuk culture is different from Old Bering Sea in its tools, house shapes, harpoon styles, and whale hunting methods. Punuk settlements were larger and more common than earlier villages. Their houses were built partly underground, square or rectangular, with wooden floors. Whale jawbones held up the houses, which were covered with skins, sod, and snow. These houses were well insulated and hidden from view.

Whaling became more important in the Punuk stage. Hunters used umiaks to kill whales in narrow ice channels and in the open sea in the fall. Open sea whaling needed skilled leaders, expert boatmen, and several boats working together. The whaleboat captain, called the umialik, is still an important person in Arctic communities today. Chipped stone tools were replaced by ground slate. Ivory winged tools were mostly replaced by tridents. Iron-tipped tools were used for engraving. Harpoon styles became simpler and more standard. Punuk art also became simpler. The Punuk people improved their hunting methods. They also created armor made from bone and developed the bow and arrow. Bone-plated wrist guards, stronger bows, bird bolas, heavy ivory net sinkers, and blunt-tipped bird arrows also appeared in the Punuk stage.

The Birnirk culture is best known along the coasts of northern and western Alaska. There are three phases: Early, Middle, and Late Birnirk. These phases are mainly known by small changes in harpoon head and arrow styles. Harpoon heads were often made of antler instead of ivory. Early Birnirk harpoons had three spurs in the middle. Middle Birnirk had two spurs, and Late Birnirk had a single spur on one side.

The Birnirk people used many of the same hunting methods and technology as Punuk and Old Bering Sea. However, there was almost no art. There is very little proof of decorated tools or weapons. The small amount of art in the Birnirk stage was limited to spirals and circles on clay pots. They used sledges, similar to those later pulled by dog teams. Birnirk people hunted sea mammals and also fished and whaled. Birnirk houses were square-shaped. Their walls were made of horizontal logs with single or double posts in each corner. Sleeping areas were at the back of the house, either raised or at floor level. No indoor fireplaces were found, but pottery pieces with fire marks suggest they used open fires a lot.

Classic Thule (1100 to 1400 AD)

During this time, the eastern Thule people spread across the High Arctic and further south. Thule people lived along the Hudson Strait coasts, in the Hudson Bay area, on the shores of the Foxe Basin, and along the Canadian mainland from the Mackenzie Delta to the Melville Peninsula. The archaeologist Alan McCartney first used the term "Classic Thule" for the people living between 1100 and 1400 AD.

The Thule people still lived in semi-underground winter houses. In the summer, they moved into skin tents, held down by circles of stone. The Thule used iron long before they met Europeans. In the west, they used small amounts of iron for carving knives and engraving tools. The iron came from meteorites and from trade with the Norse. Thule people used the metal to make stronger, harder, and more effective spear points. Iron allowed the Thule people to work with more materials to make more wood and bone tools. Their main problem was not having a steady supply of metal. The Thule were smart with technology. Reports on Classic Thule sites list many tools used for hunting. Classic Thule people did not focus much on art. There were small artistic details on household items like combs. These designs were very simple, with straight lines showing people without arms or legs, animals, or symbols about human connections to the supernatural world.

Post-Classic Thule (1400 AD to European Contact)

The Post-Classic Thule tradition existed from 1400 until Europeans arrived. In areas where whales were not as common, there is more evidence of other ways to get food. These included hunting caribou, seals, and fish. These settlements show a slower move away from whaling and using more different ways to find food. The movement of the Thule people shows the pressure from the Classic Thule population. However, the climate played a more important role. The start of the "Little Ice Age" between 1400 and 1600 limited the use of boats and the number of whales in the area. This made the season for open-water whale hunting shorter. By the 1500s, umiak and kayak whale hunting had stopped in the High Arctic. By 1600, people had moved away and left the High Arctic due to severe climate change. The Thule Eskimos who lived near open water were not as affected by the colder temperatures. During this time, local groups like the Copper Inuit, Netsilingmuit, and Inglulingmuit appeared.

Thule Expansion: East and West

Between 900 and 1100 AD, the Thule Tradition spread westward. Their housing became more efficient as they moved west. Hunting methods also improved with the use of dog sleds, umiaks, and kayaks. This allowed hunters to travel further to find and follow large game and sea mammals. After 1000 AD, the method of using polished slate for tool making continued to spread to the Aleutian Islands. Pottery making methods also spread and replaced the Norton tradition in Southern Alaska. There were differences in the areas where the tradition spread. Houses in the eastern region were more above ground and round. They had stone platforms for sleeping. Whale bones were used for the shape and support of the buildings. Eastern populations preferred soapstone items for their homes instead of pottery. They also developed the use of dogs to pull sleds.

Around the beginning of the 1000s, Thule people started moving east. As western Thule people settled the northern and western coasts of Alaska, other Thule groups moved eastward across the Canadian Arctic all the way to Greenland. Before 1000 AD, the central and eastern Canadian Arctic were home to the Dorset culture. Within a few centuries, the Dorset culture was completely replaced by Thule people who came from the west. There is not much evidence of contact between Dorset and Thule peoples. How the Dorset were replaced by the Thule is still not fully understood.

Thule culture was first found in the Eastern Arctic by Danish scientists between 1921 and 1924. A team of experts put together a huge description of the Canadian Arctic on the fifth Thule expedition. Therkel Mathiassen added to their research. He said that the tradition started in Alaska. He also said that Thule hunting relied on the dog sled, large skin boats, and kayaks. These tools allowed them to hunt over a much larger area, trade widely, and carry heavier loads. Mathiassen was right about his ideas. He even mapped out the Thule migration and their interactions with Greenland.

There are different ideas about why the Thule moved out of the Bering Strait. One idea, by R. McGhee, is that the first Thule families followed groups of bowhead whales. Whales were a very important source of food, fuel, and materials. A warming trend called the Neo-Atlantic climatic episode happened between 900 and 1200 AD in the northern hemisphere. This warming meant longer seasons of open water along the North Alaskan Coast. It also allowed bowhead whales to extend their summer range into the Beaufort Sea and further east into the Canadian Arctic islands. Whales usually avoid ice-filled channels because they can get trapped. The general warming may have reduced the amount and harshness of the sea ice. This allowed bowheads and the Thule hunters to move eastward.

Another idea is that fighting in Alaska or a desire to find new sources of iron for tools like knives may have encouraged people to move east. Archaeologists have used the spread of early Alaskan-style harpoon heads to track the paths taken by Thule people. One path follows the Beaufort Sea coast and Amundsen Gulf. It enters the High Arctic through Parry Channel and Smith Sound. A second path led the Thule south, along the western coast of Hudson Bay.

Thule Culture

The Thule people were known for using slate knives, umiaks (large open boats), seal-skin floats, and toggling harpoons. They mainly got their food from marine animals, especially large sea mammals.

Thule winter settlements usually had one to four houses, with about ten people in each. Their houses were made from whale bones from their summer hunts. Other structures included hunting sites, places to store food, and tent camps. Some larger settlements might have had more than a dozen houses. However, not all were lived in at the same time by the roughly fifty residents.

Thule Tools

The different stages of the Thule Tradition are known by their unique styles of tools and art. The later stages, Punuk and Birnirk, have more remains found by archaeologists. They are thought to have spread further and lasted longer than the earlier Old Bering Sea Stage. The Thule people are famous for their advanced transportation and hunting tools and methods. The harpoon was very important for whaling. The Thule people made several types of harpoon points from whale bone. They also made inflated harpoon line floats. These helped them hunt larger prey. Where available, they used and traded iron from meteorites, such as the Cape York meteorite.

How the Thule Got Food

The Classic Thule tradition relied heavily on the bowhead whale to survive. This is because bowhead whales swim slowly and sleep near the water's surface. Bowhead whales served many purposes for the Thule people. They provided a lot of meat for food. Their blubber gave oil for fires, light, and cooking. Their bones could be used for building structures and making tools. Outside of whaling communities, the Thule people mostly survived on fish, large sea mammals, and caribou. Because they had advanced transportation, they could reach a wider range of food sources.

There are many well-preserved animal remains at Thule sites. This is due to their relatively recent age and the cold Arctic environment. Most of the bowhead artifacts came from whales that were hunted alive. The Thule became experts at hunting and using as many parts of an animal as possible. This knowledge, along with their growing number of tools and ways to travel, allowed the Thule people to do well. They whaled together. One person would shoot the whale with a harpoon, and others would throw floats on it. They all worked together to bring the whale to land and butcher it. They shared the meat with the whole community. Their teamwork played a big part in how long they thrived in the Arctic.

Thule Sites and Projects

Several important archaeological research projects have been done on the Thule culture. These include sites like the Torngat Archaeological Project, Somerset Island, The Clachan site, Coronation Gulf, Nelson River, Baffin Island, Victoria Island, the Bell site, Devon Island – QkHn-12, and Cape York.

Genetics of the Thule People

A genetic study published in the journal Science in 2014 looked at the remains of many Thule people. These people were buried between about 1050 AD and 1600 AD. The study found that most of these individuals belonged to a specific maternal genetic group called A2a. Some samples also showed A, A2b, and D3a2a. The study suggested that the Thule people likely came from the Birnirk culture in Siberia. They were genetically very different from the native Dorset people of northern Canada and Greenland. The Thule people completely replaced the Dorset culture and their genes around 1300 AD. The study found no evidence that the Thule people mixed genetically with the Greenlandic Norse people.

de:Inuit-Kultur#Kulturgeschichtlicher Überblick

See also

In Spanish: Thule (pueblo) para niños

In Spanish: Thule (pueblo) para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |