Dakota War of 1862 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dakota War of 1862 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sioux Wars and the American Civil War | |||||||

1904 painting "Attack on New Ulm" by Anton Gag |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Dakota | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Little Crow Shakopee Red Middle Voice Mankato † Big Eagle Cut Nose |

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 77 USV, and 29 volunteers killed 358 civilians killed |

150 dead, 38 executed+2 executed November 11, 1865 | ||||||

The Dakota War of 1862 was a fight between the United States and some groups of eastern Dakota people, also known as the Santee Sioux. It started on August 18, 1862, in southwest Minnesota. This conflict is also known by other names, like the Sioux Uprising or Little Crow's War.

Before the war, the Dakota had given up large areas of their land to the U.S. government. They did this through several treaties in exchange for money and supplies. The Dakota were moved to a reservation, a special area of land set aside for them. On this land, they were told to become farmers instead of continuing their traditional hunting way of life.

At the same time, many new settlers moved into Minnesota. In 1861, there was a crop failure, meaning not enough food grew. This, along with a hard winter and less wild game to hunt, caused great hardship for the Dakota. By the summer of 1862, tensions grew because the U.S. government was late with its promised payments to the Dakota. Traders also refused to give the Dakota food on credit, partly because of the American Civil War.

On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men killed five settlers. After this, a leader named Little Crow decided to attack the Lower Sioux Agency the next day. This started the war, which led to many battles and much suffering.

Contents

Why the War Started

Land and Broken Promises

The U.S. government and Dakota leaders signed treaties in 1851. In these agreements, the Dakota gave up huge parts of their land in Minnesota Territory. In return, the U.S. promised them money and supplies.

The Dakota were supposed to live on a reservation along the Minnesota River. However, the U.S. Senate later changed the treaties. They removed the parts that set aside these reservations. Also, much of the promised money went to traders for debts the Dakota supposedly owed.

Money Problems and Hunger

When Minnesota became a state in 1858, Dakota leaders, including Little Crow, went to Washington. They wanted to talk about the treaties. Instead, they lost even more land along the Minnesota River. This made Little Crow less respected among his people.

New settlers used the land for farming and logging. This destroyed forests and prairies. It made it hard for the Dakota to farm, hunt, fish, and gather wild rice. Hunting by settlers also greatly reduced animals like bison and deer. This meant less food for the Dakota and less fur to trade.

The U.S. government was supposed to make payments, but they were often late. When the war started, they were two months behind on money and food. The government was busy fighting the American Civil War. Much of the reservation land was not good for farming. Hunting could no longer feed the Dakota. They became very unhappy about losing their land, not getting payments, and facing hunger.

A Trader's Harsh Words

On August 15, 1862, some Dakota groups went to the Lower Sioux Agency for food. The Indian Agent, Thomas J. Galbraith, would not give them food without payment.

At a meeting, Dakota representatives asked a trader named Andrew Myrick to sell them food on credit. Myrick reportedly said, "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung." This comment deeply angered Little Crow and his people. Little Crow later said Myrick's words were a main reason for starting the war.

The promised treaty payments finally arrived in St. Paul on August 16. They reached Fort Ridgely the next day. But it was too late to stop the fighting.

The War Begins

Acton Incident and Attack Plans

On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men were hunting. They killed five settlers near Acton Township, Minnesota. Some stories say they did it on a dare. Others say the farmer refused them food or water.

The four men knew they were in trouble. They went to their leaders, including Cut Nose and Chief Shakopee III. They all went to Little Crow's village. That night, a war council was held at Little Crow's house. Other leaders like Mankato and Big Eagle were there.

The leaders disagreed about what to do. Many say Little Crow was against fighting at first. But a young warrior called him a coward. By morning, Little Crow ordered an attack on the Lower Sioux Agency.

Historian Mary Wingerd says that not all Dakota fought. She believes fewer than 1,000 men out of 7,000 Dakota were involved. Many tribal elders did not want to fight.

Attack on the Lower Sioux Agency

On August 18, 1862, Little Crow led a surprise attack on the Lower Sioux Agency. Thirteen clerks, traders, and government workers were killed. Ten people were taken captive. About 47 people managed to escape.

Soldiers from Fort Ridgely tried to stop the uprising. They were defeated at the Battle of Redwood Ferry. Twenty-four soldiers, including their leader Captain John Marsh, died. Dakota warriors then swept through the Minnesota River Valley. They killed many settlers and burned towns like Milford and Leavenworth.

Captives Taken

The Dakota took many captives, mostly women and children. This created a problem for the Dakota leaders. Some, like Big Eagle, wanted to return them to the fort. But Little Crow believed they were important for the war effort. He wanted to keep them safe. Over time, different Dakota families helped care for the captives.

Dakota Attacks and Defenses

Battles at New Ulm and Fort Ridgely

After their first success, the Dakota attacked New Ulm on August 19 and again on August 23, 1862. The people of New Ulm had set up defenses in the town center. They managed to hold off the Dakota during the short attack. Dakota warriors burned much of the town. A thunderstorm that evening stopped further attacks.

Soldiers and local fighters from nearby towns helped defend New Ulm. They continued to build barricades around the town.

The Dakota also attacked Fort Ridgely on August 20 and 22, 1862. They could not take the fort. But they ambushed a group of soldiers going from the fort to New Ulm. This limited the U.S. forces' ability to help other settlements. The Dakota raided farms and small towns across southern Minnesota.

Defending the Southern Border

On August 28, Governor Ramsey sent Judge Charles Eugene Flandrau to protect the southern border of Minnesota. Flandrau became a colonel in the militia. He set up his headquarters near Mankato with 80 men. He organized a line of forts with soldiers under his command. These forts were in towns like New Ulm and Garden City.

In Iowa, people were worried about the Dakota attacks. They built a line of forts from Sioux City to Iowa Lake. Although no fighting happened in Iowa, the Dakota uprising led to the removal of the remaining Dakota people from the area.

Battle of Birch Coulee

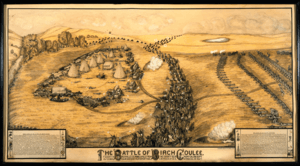

On August 31, Colonel Sibley sent 153 men to bury dead settlers and soldiers. In the early morning of September 2, 1862, about 200 Dakota warriors surrounded and attacked their camp. This started the Battle of Birch Coulee, a 31-hour fight. Colonel Sibley arrived with more troops and cannons on September 3. The U.S. military suffered many losses, with 13 soldiers dead and nearly 50 wounded. Only two Dakota soldiers were confirmed dead.

Attacks in Northern Areas

Further north, the Dakota attacked stagecoach stops and river crossings. These were along the Red River Trails, a trade route in northwestern Minnesota. Many settlers and workers hid in Fort Abercrombie. Between late August and late September, the Dakota attacked Fort Abercrombie several times. The fort's defenders, including soldiers and citizens, fought them off.

Boat traffic on the Red River stopped. Mail carriers and soldiers were killed trying to reach other towns. Eventually, more soldiers came to Fort Abercrombie. The people hiding there were moved to St. Cloud, Minnesota.

More Soldiers Arrive

The American Civil War made it hard for Minnesota to get help. Governor Alexander Ramsey asked for assistance from other states and President Abraham Lincoln. On September 6, 1862, General John Pope was put in charge of the military in the Northwest. He was ordered to stop the violence. Pope arrived in Minnesota on September 16. He told Colonel Sibley to act quickly.

Minnesota began recruiting more soldiers in July 1862. When the war started in August, new regiments were quickly formed. Many soldiers who were home on leave were called back. New recruits were asked to join, bringing their own weapons and horses if they could.

Sibley was worried his troops were not experienced enough. He asked for the 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment to return to Minnesota. These soldiers had been captured by the Confederates but were later released. They joined Sibley's forces on September 13.

End of the War

Battle of Wood Lake

The last major battle of the war was the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. It was a victory for the U.S. forces led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley. Sibley's army had 1,619 men. They had better weapons, like rifled muskets and artillery with exploding shells.

Little Crow and his warriors knew Sibley was coming. They planned to attack Sibley's troops as they marched. On the night of September 22, Little Crow's warriors moved into position. They hid in the tall grass, waiting for morning.

But on September 23, around 7 am, some U.S. soldiers left camp in wagons to find potatoes. About half a mile from camp, they were attacked by 25 to 30 Dakota warriors. This started the Battle of Wood Lake. The U.S. soldiers fought back.

The battle lasted about two hours. Little Crow and the Dakota warriors retreated. Chief Mankato was killed by a cannonball. Many Dakota fighters could not join the battle because they were too far away. Sibley did not chase the retreating Dakota because he did not have enough cavalry. His men buried 14 fallen Dakota. Sibley lost seven men, and 34 were wounded. This battle effectively ended the war.

Surrender at Camp Release

At Camp Release on September 26, 1862, a group of Dakota who wanted peace handed over 269 prisoners to Colonel Sibley's troops. These captives included 162 "mixed-bloods" (people of mixed heritage) and 107 white people, mostly women and children. Little Crow and some of his followers fled to the northern plains.

Many Dakota warriors who had fought in battles later joined the "friendly" Dakota at Camp Release. They did not want to spend winter on the plains. Sibley had promised to punish only those who had killed settlers.

The surrendered Dakota warriors and their families were held while military trials took place. Out of 498 trials, 303 men were found guilty and sentenced to death. President Lincoln reviewed the cases. He approved the death sentences for 39 men. One sentence was later changed, so 38 men were executed.

Little Crow's Escape and Death

Little Crow fled north on September 24, after the Battle of Wood Lake. He hoped to get help from other Native American tribes and from the British in Canada. But he did not get much support.

Little Crow eventually returned to Minnesota in late June 1863. He was killed on July 3, 1863, near Hutchinson, Minnesota. He was gathering raspberries with his teenage son, Wowinape. Nathan Lamson and his son saw them while hunting. Lamson and Little Crow exchanged fire, and Little Crow was fatally wounded.

Weeks later, when it was confirmed it was Little Crow, Lamson received a $500 reward from Minnesota.

After the War

Trials and Executions

On September 27, 1862, Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley ordered military trials for the Dakota. Later, it was decided that Sibley did not have the authority to hold these trials. The trials themselves were very quick. Some lasted less than 5 minutes. The Dakota did not have lawyers, and no one explained the process to them.

A legal expert named Carol Chomsky wrote that the Dakota were tried by a military group made of Minnesota settlers. They were found guilty of killings that happened during wartime. She noted that in other wars between Americans and Native American nations, the U.S. did not punish those defeated in war with criminal charges.

The trials happened in a very hostile environment. Many people in Minnesota were very angry at the Dakota. By November 3, 392 Dakota men had been tried. The military group announced that 303 Dakota prisoners were sentenced to death.

President Lincoln was told about the sentences. He asked for all the trial records. He wanted to know who was most guilty. Lincoln reviewed the records with the help of two lawyers. He wanted to be fair, not too harsh or too lenient.

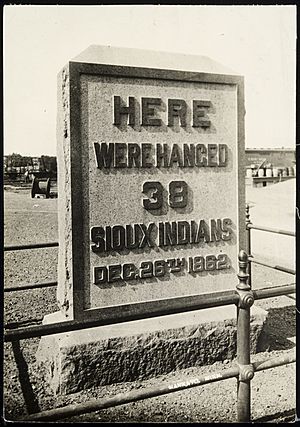

On December 11, 1862, Lincoln announced his decision. He said he looked for those who had harmed women and those who had taken part in massacres, not just battles. He found 40 men in this group. He decided to execute 39 of them. One sentence was changed later, making it 38 men. They were executed by hanging on December 26, 1862.

Lincoln's decision to spare most of the men caused protests in Minnesota. But Lincoln reportedly said, "I could not afford to hang men for votes."

Imprisonment and Exile

The Dakota who were not executed were kept in prison that winter. The next spring, they were moved to Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa. They stayed there from 1863 to 1866. Many prisoners died from disease. The survivors were sent with their families to Nebraska. Their families had already been forced out of Minnesota.

During their time in prison, missionaries tried to convert the Dakota to Christianity. The Dakota prisoners also made and sold crafts like rings and beadwork. They used the money to buy blankets, clothes, and food for themselves and their families. They also sent money and supplies to their families who had been sent to the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota.

In April 1864, the imprisoned Dakota helped pay for a missionary to go to Washington, D.C. He argued for their release. President Lincoln listened, but only a few Dakota were released at that time. The rest were finally released two years later, in April 1866, by President Andrew Johnson. They were then moved to the Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska.

Pike Island Internment

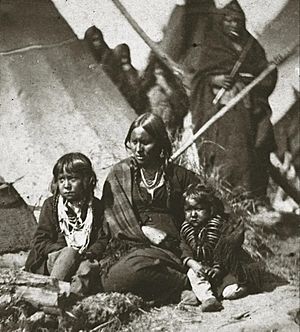

On November 7, 1862, about 1,658 Dakota non-combatants, mostly women, children, and elders, began a 150-mile journey. They traveled from the Lower Sioux Agency to Fort Snelling. They were protected by soldiers. The soldiers asked people along the way to remember that these were "friendly Indians, women and children." However, when they reached Henderson, an angry crowd attacked the Dakota, badly hurting a baby.

They arrived at Fort Snelling on November 13, 1862. They were first in an open camp, then moved to a fenced area for protection. Conditions were bad, and diseases like measles spread. Many Dakota died there.

In April 1863, the U.S. Congress ended the Dakota reservation. They declared all treaties with the Dakota invalid. They decided to remove the Dakota people entirely from Minnesota. The state even offered a bounty of $25 for the scalp of any Dakota male found free in the state. Only 208 Mdewakanton, who had stayed neutral or helped settlers, were allowed to remain.

In May 1863, the 1,300 surviving Dakota were put on two steamboats. They were moved to the Crow Creek Reservation in Dakota Territory. This place was suffering from drought, making it hard to live there. Many more Dakota died during the journey and within six months of arriving.

Minnesota After the War

During the war, at least 30,000 settlers left their farms and homes in Minnesota. A year later, no one had returned to 19 of the 23 counties affected by the conflict.

After the American Civil War, people began to resettle the area. By the mid-1870s, European Americans were again using the land for farming.

The federal government later created the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation near Morton. Much later, in the 1930s, the smaller Upper Sioux Indian Reservation was created near Granite Falls.

Most Dakota were forced out of Minnesota, even those who had opposed the war or helped settlers. However, by the 1880s, some Dakota families moved back to the Minnesota River valley. These included the Good Thunder, Wabasha, Bluestone, and Lawrence families.

The stories of the war have been passed down through generations. Settlers' descendants remember the pioneer farmers being killed. Dakota descendants remember their people losing their land and being sent into exile.

The New Ulm Battery, a local militia formed during the uprising, is still active today. It is the only Civil War-era militia remaining in the U.S.

Land Returned

On February 12, 2021, the Minnesota government and the Minnesota Historical Society gave back half of the lands near the Battle of Lower Sioux Agency to the Lower Sioux Community. This included about 115 acres from the Historical Society and 114 acres from the state government.

Lower Sioux President Robert Larsen said, "I don't know if it's ever happened before, where a state gave land back to a tribe." He added that their ancestors "paid for this land over and over with their blood, with their lives. It's not a sale; it's been paid for by the ones that aren't here anymore."

Monuments and Memorials

- The Camp Release State Monument remembers the surrender of many Native Americans and the release of 269 captives on September 26, 1862. It also honors the U.S. victory at Wood Lake.

- The Wood Lake Battlefield State Monument was built in 1910. It honors the U.S. soldiers who died at the Battle of Wood Lake.

- The Birch Coulee Battlefield in Morton, Minnesota, has trails and markers. These tell the story of the battle from both the U.S. and Dakota points of view.

- The Faithful Indians' Monument was built in 1899. It honors Dakota people who stayed loyal and saved white settlers.

- The Fort Ridgely State Monument was built in 1896. It remembers the soldiers and citizens who defended the fort during the siege.

- The Henderson Monument is dedicated to five members of the Henderson family who were killed.

- The Radnor Erle Monument remembers Erle, who died saving his father's life.

- The Schwandt State Monument was built in 1915. It remembers six members of the Schwandt family and a friend who were killed.

- The Redwood Ferry Monument honors Captain John Marsh and 24 men who died in an ambush on August 18.

- The Defenders State Monument was built in 1890 in New Ulm. It honors the citizens who helped defend the town.

- The "Hanging Monument" in Mankato, Minnesota, was a large stone marker. It was built in 1912 to remember the execution of 38 Dakota men. It was removed in 1971 due to protests from Native American groups. Its current location is unknown.

- Reconciliation Park in Mankato was created in 1997. It aims to help heal relations between Dakota and non-Dakota peoples. It has a large buffalo statue and a quote from a Dakota spiritual leader. In 2012, a memorial with the names of the 38 executed men was added.

- The Acton State Monument was built in 1909. It marks where the first killings happened on August 17, 1862.

- The Guri Endreson-Rosseland State Monument honors Mrs. Guri Enderson-Rosseland. She survived an attack and helped wounded settlers.

- The White Family Monument is near Brownton, Minnesota. It remembers the four members of the White family who were killed.

- The Lake Shetek State Park monument remembers 15 white settlers killed there.

- A stone monument was built in 1929 near where Little Crow was killed by Nathan Lamson.

Commemorative Events

- The annual Mankato Pow-wow is held in September. It remembers the lives of the executed men. It also aims to bring together European-American and Dakota communities.

- In 2012, for the 150th anniversary of the executions, a group of Dakota rode horses from South Dakota to Mankato. This journey was filmed for the documentary Dakota 38. This memorial ride continues every year.

In Popular Media

- In the book Little House on the Prairie (1935), Laura asks her parents about the Minnesota massacre, but they do not tell her details.

- The uprising is important in the historical novel The Last Letter Home (1959) by Swedish author Vilhelm Moberg. This book is part of his The Emigrants series.

- These novels were made into Swedish films, The Emigrants (1971) and The New Land (1972). The second film shows the Dakota Wars and the mass execution.

- Poet Layli Long Soldier's poem "38" is about the massacre.

- Minnesota House of Representatives member Dean Urdahl wrote a historical fiction novel called "Uprising" in 2007, followed by sequels.

Several works were made for the 150th anniversary:

- The This American Life episode "Little War on the Prairie" (2012) talks about the lasting impact of the conflict.

- The Past Is Alive Within Us: The U.S.- Dakota Conflict (2013) is a video documentary. It looks at Minnesota's role in the Dakota War and shares current stories.

- Dakota 38 (2012) is a film that shows the long horse ride made by a group of Dakota in 2008. They rode over 330 miles to Mankato to encourage healing and understanding.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |