Pacific Fur Company facts for kids

A drawing of a North American beaver. Their fur was the main product collected by the company.

|

|

| Private | |

| Industry | Fur trade |

| Fate | Sold to competitors |

| Successor | North West Company |

| Founded | New York City, U.S., (1810) |

| Founder | John Jacob Astor |

| Defunct | 1813 |

| Headquarters | |

|

Area served

|

Pacific Northwest |

|

Key people

|

Wilson Price Hunt, Duncan McDougall, Alexander McKay, David Stuart |

| Total assets | $200,000 (1810) |

| Parent | American Fur Company |

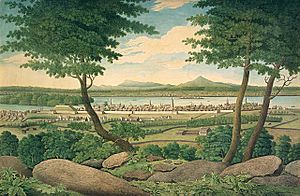

The Pacific Fur Company (PFC) was an American business that operated from 1810 to 1813. It was owned by John Jacob Astor. The company's goal was to trade furs in the Pacific Northwest. At that time, this region was not part of any single country. The United Kingdom, Spain, Russia, and the United States all wanted to control the area.

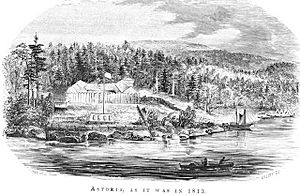

The company sent workers to the Pacific Coast by land and by sea. In 1811, they built a base called Fort Astoria near the Columbia River. This is now the city of Astoria, Oregon. The company faced many problems. One of their ships, the Tonquin, was destroyed. They also had to compete with a Canadian business called the North West Company.

The group that traveled by land faced hunger and difficult terrain. The War of 1812 made it hard to protect the business. In 1813, the company was sold to the North West Company. Although the business did not last long, the explorers found important paths through the Rocky Mountains. These paths were later used by settlers on the Oregon Trail.

Contents

Formation of the Company

John Jacob Astor was a merchant from New York City. He started the American Fur Company. He wanted to build a line of trading posts from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. To do this, he created the Pacific Fur Company in 1810.

Astor paid $200,000 to start the business. This was a lot of money at the time. He divided the ownership into 100 shares. He kept half of the shares for his company. The other shares were given to the men who would run the business.

Astor hired men who knew about the fur trade. Some of them used to work for Canadian companies. The partners met in New York in June 1810 to sign the agreement. Astor planned to send two groups to the Oregon Country. One group would go by ship around South America. The other group would walk across the continent. They planned to trade beads, blankets, and copper with Native Americans for furs.

Hiring Workers

The company needed many workers. They needed fur trappers and Voyageurs (travelers who moved goods by canoe). The leaders went to Montreal, Canada, to hire men.

The Overland Group

Wilson Price Hunt was chosen to lead the group that would travel by land. He was a businessman from St. Louis. He did not have much experience in the wilderness. He hired men in Montreal and Mackinac Island.

The workers were promised good pay. They would get a higher salary than usual and a five-year contract. The group gathered in St. Louis in September 1810. They bought supplies and prepared for the long journey.

The Sea Voyage

The first group traveled by ship to build the main trading post. They sailed on a ship called the Tonquin. The ship was commanded by Captain Jonathan Thorn.

Journey of the Tonquin

The Tonquin left New York on September 8, 1810. There were 33 company workers on board. The captain was very strict. He did not get along with the workers. The ship sailed around Cape Horn at the bottom of South America.

In February 1811, the ship stopped in Hawaii. They bought fresh food like coconuts, yams, and hogs. They also hired 24 Native Hawaiian workers to help them.

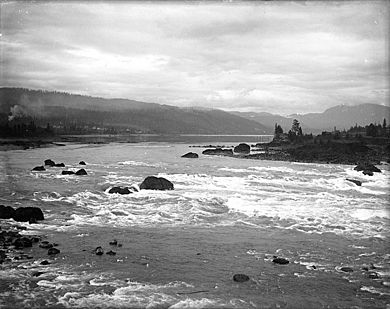

The ship reached the Columbia River in March 1811. The water at the mouth of the river was very rough. The captain sent small boats to find a safe path. Sadly, the boats tipped over, and eight men lost their lives. The ship finally entered the river on March 24.

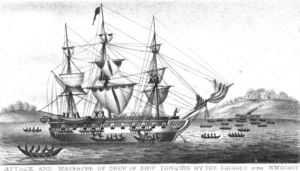

Later, the Tonquin sailed north to trade for furs. Near Vancouver Island, the crew got into a conflict with the Tla-o-qui-aht people. The ship was destroyed, and the crew was lost. This was a disaster for the company because they lost their ship and many supplies.

Building Fort Astoria

The workers started building Fort Astoria in April 1811. It was located near the mouth of the Columbia River. The land was covered with thick forests. The trees were huge and hard to cut down. Most of the men did not know how to cut such big trees. It took days to cut down just one tree.

Many men got sick while working. They did not have a doctor, so it was hard to treat illnesses. Despite the hard work, they built a small fort to live in and store their goods.

Fort Okanogan

In July 1811, a group led by David Stuart traveled up the river. They met the Syilx people (also known as the Okanogan people). The Syilx were friendly and welcomed the traders. They built a trading post called Fort Okanogan. This was the first American settlement in what is now Washington state.

Native American Neighbors

The people at Fort Astoria relied on the local Chinookan tribes. The most powerful leader was Comcomly. He helped the new settlers.

Trading for Food

The settlers often ran out of food. They traded with the Chinookan people for fish. The Columbia River had many fish, like salmon and sturgeon. The Native Americans were expert fishermen. They also sold wapato roots, which are like potatoes.

The settlers bought hats from the Native Americans. These hats were woven tightly and kept the rain off. This was very useful in the rainy Pacific Northwest.

Relationships

The relationship between the settlers and the Native Americans was mostly peaceful, but sometimes there was fear. The settlers built fences and guarded their fort because they were worried about attacks. However, trade continued because both sides benefited from it.

The Overland Expedition

Wilson Price Hunt led the group that walked across the continent. It was a very hard journey. They left St. Louis in October 1810.

Traveling up the River

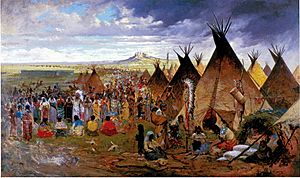

The group traveled up the Missouri River. They met the Omaha and Sioux nations. In May 1811, they met a large group of Sioux warriors. They had a meeting and smoked a peace pipe. The Sioux let them pass.

Later, they met traders from a rival company. They also met the Arikara people. Hunt decided to leave the river and travel by land to avoid the Blackfoot nation, who were known to be strong warriors.

Crossing the Mountains

The group bought horses from the Cheyenne and Crow nations. They crossed the Rocky Mountains in what is now Wyoming. The journey was difficult.

The Snake River

When they reached the Snake River, they made canoes. They thought it would be easier to travel by water. This was a mistake. The river had dangerous rapids and waterfalls. Some canoes tipped over, and they lost supplies.

They ran out of food. The men were starving. They had to split into smaller groups to find food. They traded with the Shoshone people for dried fish and dogs to eat.

Arrival

The groups slowly made their way to the Columbia River. They were helped by the Umatilla and Wasco-Wishram people. The first group arrived at Fort Astoria in January 1812. The main group led by Hunt arrived in February. They were exhausted and their clothes were in rags.

The End of the Business

In 1812, the War of 1812 began between the United States and the United Kingdom. The workers at Fort Astoria learned about the war in 1813. They were worried that a British warship would come and capture them.

The company was also running out of money and supplies. The partners decided to sell the fort and all their furs to the North West Company. This was a British company.

On December 12, 1813, a British ship called the HMS Racoon arrived. The captain took control of the fort and renamed it Fort George. The Pacific Fur Company was finished.

Why It Matters Today

Even though the Pacific Fur Company did not last long, it was important for history.

- Exploration: The men who traveled back to the east discovered the South Pass. This is a wide gap in the Rocky Mountains. Later, thousands of pioneers used this pass on the Oregon Trail to move west.

- Claims: The company's presence helped the United States claim the Oregon Country later on.

- Literature: The famous writer Washington Irving wrote a book called Astoria in 1836. It told the story of the company and made the West famous.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pacific Fur Company para niños

In Spanish: Pacific Fur Company para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |