Shoshone Falls facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Shoshone Falls |

|

|---|---|

Shoshone Falls in August 2018

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Infobox_mapframe at line 185: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Jerome/Twin Falls County, Idaho, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 42°35′43″N 114°24′03″W / 42.59528°N 114.40083°W |

| Type | Block |

| Elevation | 3,255 ft (992 m) at crest |

| Total height | 212 ft (65 m) |

| Number of drops | 1 |

| Total width | 925 ft (282 m) |

| Watercourse | Snake River |

| Average flow rate |

3,530 cu ft/s (100 m3/s) |

Shoshone Falls is a huge waterfall on the Snake River in southern Idaho, United States. It's about 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of the city of Twin Falls. People sometimes call it the "Niagara of the West." Shoshone Falls is 212 feet (65 m) high, which is 45 feet (14 m) taller than Niagara Falls! It flows over a wide edge that is almost 1,000 feet (300 m) across.

This amazing waterfall was formed by a giant flood from Lake Bonneville about 14,000 years ago, during the last Pleistocene Ice Age. Shoshone Falls was the natural end point for fish like salmon swimming upstream in the Snake River. This made it a very important place for Native Americans to fish and trade.

Europeans first wrote about the falls in the 1840s. Even though it was in a far-off place, it became a popular spot for tourists starting in the 1860s. Later, in the early 1900s, some of the Snake River's water was moved to help grow crops in the Magic Valley. Today, you can see the falls at their best in spring. The amount of water flowing over them changes with the snowmelt, how much water is needed for farms, and for making electricity. The power plants and irrigation systems built here helped southern Idaho's economy grow a lot.

The City of Twin Falls owns and runs a park where you can see the waterfall. The best time to visit is in the spring. In late summer and fall, less water flows over the falls because it's used for irrigation. The water flow can be huge, over 20,000 cubic feet per second (570 m3/s), in wet springs. But in dry years, it can be as low as 300 cubic feet per second (8.5 m3/s).

Contents

Discover Shoshone Falls: A Natural Wonder

Shoshone Falls is located in the Snake River Canyon. It sits on the border between Jerome and Twin Falls Counties. The falls are about 615 miles (990 km) upstream from where the Snake River joins the Columbia River. It's the tallest of several waterfalls in this part of the Snake River. It's about 2 miles (3.2 km) downstream from Twin Falls and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) upstream from Pillar Falls.

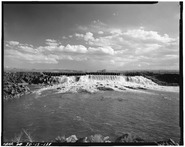

Right above Shoshone Falls, the Snake River gets narrow, less than 400 feet (120 m) wide. It then rushes over rapids and islands before dropping over a vertical, horseshoe-shaped cliff. This cliff is 212 feet (65 m) high and 925 feet (282 m) wide. How the falls look changes a lot depending on how much water is in the Snake River. When there's a lot of water, the falls look like one big sheet of water across the whole river. When water levels are low, the falls split into four or more separate drops. The widest part, on the north side, is also called Bridal Veil Falls.

Water Flow at Shoshone Falls

Shoshone Falls is in a dry area. Most of its water naturally comes from melting snow in the Rocky Mountains of Idaho and Wyoming. This includes areas near Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. Some water also comes from springs in the Snake River Canyon.

Today, many reservoirs and huge water diversions for farming have greatly reduced the water reaching the falls. Now, the canyon springs are the main source of water. The Snake River's average flow at Twin Falls is 3,530 cubic feet per second (100 m3/s). For comparison, the average flow at Idaho Falls, which is 190 miles (310 km) upstream, is 5,911 cubic feet per second (167.4 m3/s). Below Milner Dam, 24 miles (39 km) upstream, the average flow is only 884 cubic feet per second (25.0 m3/s). It's often zero in late summer and fall.

Idaho Power's Shoshone Falls Dam is right upstream from the falls. It sends water to the Shoshone hydroelectric plant, which further reduces the water going over the falls. Idaho Power must keep a minimum "scenic flow" of 300 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])* during the day from April through Labor Day. But even this small amount can be hard to achieve if there isn't enough water in the Snake River. Most water for farming is needed in the summer, which is also when most tourists visit. The Shoshone power plant uses up to 950 cubic feet (27 m3) of water per second. So, the falls will only get more water if the Snake River's flow is more than what the plant needs and the scenic flow requirement. The best time to see the falls is between April and June, when snowmelt is high. Also, water is released from upstream reservoirs to help steelhead fish migrate.

The highest flow ever recorded at Twin Falls was 32,200 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])* on June 10, 1914. The lowest was 303 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])* on April 1, 2013. June usually has the most water, at 6,280 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])*. August typically has the least, at 956 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])*.

How Shoshone Falls Was Formed

Most of the rocks under the Snake River Plain came from huge lava flows. These flows happened over millions of years due to eruptions from the Yellowstone hotspot. Shoshone Falls flows over a 6-million-year-old lava flow that is very hard. This hard rock crosses softer rock layers of the Snake River Plain. This creates a natural step that resists water erosion.

The falls themselves were created very quickly during the huge Bonneville Flood. This happened at the end of the Pleistocene Ice Age, about 14,500–17,500 years ago. At that time, Lake Bonneville, a giant freshwater lake that covered much of the Great Basin, overflowed into the Snake River. About 1,100 cubic miles (4,600 km3) of water was released. This was 1500 times the average yearly flow of the Snake River at Twin Falls! This massive flood carved the Snake River Canyon in just a few weeks. It also shaped waterfalls like Shoshone Falls where the local rock met harder layers underneath.

The enormous Snake River Aquifer is a huge underground water supply. It is formed in the porous volcanic rock of the region. Each year, melting snow from the surrounding mountains refills it. Because the Shoshone Falls canyon is lower than the land around it, groundwater is pushed to the surface. This happens through large springs in the canyon walls. Even though almost all the river water is taken upstream from Milner Dam, these springs can provide up to 3,000 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])* of water to the falls. The flow from these springs changes a lot with the seasons. However, it has increased since the 1950s. This is because irrigation water on the surrounding plain soaks into the aquifer.

Wildlife at Shoshone Falls

Because it is so tall, Shoshone Falls stops fish from swimming upstream. Fish that live in the ocean but return to fresh water to lay eggs, like salmon and steelhead/rainbow trout, cannot pass the falls. Other migrating fish, like sturgeon, also cannot get past. Before many dams were built on the Snake River below Shoshone Falls, spawning fish would gather in huge numbers at the bottom of the falls. They were a major food source for local Native Americans.

Yellowstone cutthroat trout lived above the falls. They filled the same role as rainbow trout below the falls. However, their numbers have gone down since the 1800s due to river diversions and competition from new species like lake trout. Because of this big difference, the World Wide Fund for Nature uses Shoshone Falls as the dividing line between the Upper Snake and the Columbia Unglaciated freshwater ecoregions. The Snake River above Shoshone Falls shares only 35 percent of its fish species with the lower Snake River below the falls. Fourteen fish species found in the upper Snake are also found in the Bonneville freshwater ecoregion (which covers part of Utah), but not in the lower Snake or Columbia rivers. The upper Snake River also has many unique freshwater mollusks (like snails and clams) that are found nowhere else.

History of Shoshone Falls

Native Peoples and Early Explorers

Shoshone Falls is named after the Lemhi Shoshone or Agaidika people, also known as "Salmon eaters." They relied on the Snake River's huge salmon runs for most of their food. They also ate roots, nuts, and hunted large animals like buffalo. Since the falls were the farthest point salmon could swim upstream in the Snake River, they became a key food source and trading spot for native peoples. They used willow spears with elk horn tips to catch fish. The Bannock people also visited Shoshone Falls every summer to gather salmon.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition met the Shoshone Indians in 1805-06, but they did not go through the Shoshone Falls area. The 1811 Wilson Price Hunt Expedition aimed to find new routes for the fur trade. They traveled down the Snake River to Caldron Linn, a wild rapids near today's Murtaugh, Idaho. There, a canoe flipped, and one of Hunt’s boatmen drowned. Although the group explored the canyon for several miles downstream, Hunt’s journal does not mention any waterfalls as big as Shoshone Falls. Hunt then split his group to find food more easily, and they left Idaho. The paths they explored later became part of the Oregon Trail. This trail would bring many settlers from the eastern United States to the Shoshone Falls area.

For the next thirty years, American and British-Canadian fur trappers hunted in south-central Idaho. They likely saw Shoshone Falls. However, none of their journals mentioned the waterfall.

John C. Frémont passed near Shoshone Falls during his 1843 expedition. His goal was to map the western part of the Oregon Trail. But his group did not see the falls. They left the river canyon and cut across a sandy plain to Rock Creek. They returned to the canyon rim where Rock Creek enters the Snake River. There, he saw the Thousands Springs. He described them as “a subterranean river [that] bursts out directly from the face of the escarpment.”

They went down into the canyon with some difficulty, measured the river, and continued downstream. They camped about a mile below what Frémont called "Fishing Falls." He said these falls were "a series of cataracts with very inclined planes, which are probably so named because they form a barrier to the ascent of the salmon; and the great fisheries from which the inhabitants of this barren region almost entirely derive a subsistence commence at this place." He noted that salmon were "so abundant that they [the Shoshone] merely throw in their spears at random, certain of bringing out fish." This part of the river is now known as Salmon Falls. Early meetings between Europeans and Native Americans were usually friendly. But later, serious conflicts started over land. After the Snake War, about twenty years later, the Shoshone people were moved to reservations.

More pioneers traveled along the Oregon Trail through Idaho from 1843 onward. This increased even more after Frémont’s journal was published. In 1847, about 4,000 settlers passed through on their way to Oregon. One group that year included Roman Catholic Bishop Augustin-Magloire Blanchet. He was appointed to lead the new Diocese of Walla Walla. Traveling along the north side of the river, the group took a detour, perhaps guided by a former trapper. Blanchet then made the first known written record of seeing Shoshone Falls. Being from Quebec, Canada, he called the feature “Canadian Falls.”

That name did not last long. In August 1849, a group of U.S. Army “Mounted Rifles” marched by, heading for Oregon. They took a route closer to the canyon and could hear the thunder of the falls. A local Indian had told their guide about the falls. So, the guide led Lieutenant Andrew Lindsay and George Gibbs, a writer and artist, to see them. Gibbs drew the first known picture of the falls. They chose “Shoshone Falls” as a more fitting name.

The 1868 Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, led by U.S. Geological Survey director Clarence King, was the first to closely study the geology, soils, and minerals of the Shoshone Falls area. King described the area as "strange and savage." Of the falls, he said: "You ride upon a waste. Suddenly, you stand upon a brink. Black walls flank the abyss. A great river fights its way through the labyrinth of blackened ruins and plunges in foaming whiteness." He was also the first to guess that the falls and canyon were created by "moments of great catastrophe" rather than slow erosion over millions of years, given the region's wild volcanic history. Timothy H. O'Sullivan was also part of the 1868 expedition. He became the first national photographer to take pictures of the falls. O'Sullivan returned to the area in 1874 to photograph Shoshone Falls again.

Tourism and Development

Shoshone Falls first became a tourist spot in the mid-1800s. This was true even though the area was isolated and harsh. Travelers on the Oregon Trail often stopped to see the falls, which was only a "slight detour" to the north. People promoting tourism to the falls talked about the "lonely grandeur" of the area. They also liked that the falls were not "overshadowed by a city." This was perhaps a jab at Niagara Falls, which by then was known for lots of buildings next to it. The first time Shoshone Falls was called "The Niagara of the West" was in a Salt Lake City newspaper article. It was reprinted in the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1866. The article described the falls as "a world wonder which for savage scenery and power sublime stands unrivaled in America." The falls were painted by Thomas Moran in 1900 for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition. Moran was famous for his paintings of wild Western landscapes like Yellowstone.

In 1869, gold was found in the Snake River Canyon near Shoshone Falls. By 1872, about 3,000 miners had come to the area looking for gold. The richest gold was said to be between Murtaugh, about 15 miles (24 km) above Shoshone Falls, and Clark's Ferry, about 20 miles (32 km) below the falls. The towns of Shoshone City, Springtown, and Drytown grew because of the gold rush. However, the boom quickly ended. The local geology and how the sediment was deposited made it hard to get the gold out. The first miners were mostly from Europe. Later, Chinese miners took over and continued to work the claims into the early 1880s. They looked for tiny gold particles called "gold flour."

In 1876, Charles Walgamott, a local farmer, saw that the falls could be a tourist spot. He fenced off large areas around the falls and started building a lodge. He hoped to gain ownership of the land through squatter's rights. In 1883, the Oregon Short Line Railroad was extended to Shoshone, Idaho. This made travel to the falls much easier. Walgamott then sold the land to a group of wealthy investors, including Montana Senator William A. Clark. They planned to replace the hotel with a much grander one and put a steamship on the river for fun. In April of the next year, Walgamott got a license to run a cable ferry across the Snake River upstream of the falls. This ferry was one of the most dangerous river crossings in Idaho. In 1904 and 1905, boats broke free from the cable and were swept over the falls, killing four people. Many other close calls and accidents also happened. The dangers of the crossing led to calls for a road or rail bridge across the canyon just below the falls. Although Twin Falls County officials thought the idea was "feasible," it was dropped because it was too expensive. In 1919, the Hansen suspension bridge was built across a narrower part of the Snake River Canyon, about 6 miles (9.7 km) upstream.

Farming and Less Water at Shoshone Falls

Ira Burton Perrine came to the Shoshone Falls area in 1884. He first settled at the bottom of the Snake River Canyon, where he raised cattle and grew fruit trees. Later, he got involved in the tourist business, starting a ferry and a stagecoach service, and building the Blue Lakes Hotel. However, Perrine is best known for his role in developing southern Idaho's economy through huge irrigation projects. These projects led to Shoshone Falls sometimes drying up. In 1900, the Twin Falls Land and Water Company was formed. They claimed 3,000 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])* of water from the Snake River. Perrine's main goal was to irrigate 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) of land. This would not have been allowed in other parts of the western U.S. because of rules like the Homestead Act, which limited each settler's claim to 160 acres (65 ha). But Perrine's project fit under the 1894 Carey Act. This act allowed private companies to build large irrigation systems in desert areas where the job would be too big for individual settlers.

Perrine suggested moving the Snake River's water at Caldron Linn. This spot is about 24 miles (39 km) upstream from Shoshone Falls. Senator Clark and others who owned land at Shoshone Falls sued the Twin Falls Land and Water Company. But they lost in the Idaho Supreme Court in 1904. The Milner Dam and the main canals needed to deliver water were finished by 1905. "On March 1, 1905, Frank Buhl ceremonially pulled a wheel on a winch. The gates of Milner Dam were closed, and the gates to a thousand miles of canal and laterals were opened. The Snake River was diverted, and that night Shoshone Falls went dry as the water rushed across the desert far above. Perrine's dream came true, and 262,000 acres of desert were soon changed."

Turning huge areas of desert into productive farmland almost overnight led to the region being called "Magic Valley". This project, powered entirely by gravity, was a rare successful example of private irrigation development under the Carey Act. The city of Twin Falls was officially started in 1905. Its lands were originally planned for town development as part of the irrigation project. In 1913, Perrine built an electric streetcar system to take tourists from Twin Falls to Shoshone Falls. Because of World War I, iron was in short supply, so the rail line was never fully completed as planned. The rise in car ownership after the war also made the line outdated, and it was stopped in 1916.

The Shoshone Falls Power Plant was finished in 1907 by the Greater Shoshone and Twin Falls Water Power Company. A low diversion dam (the Shoshone Falls Dam) was built right upstream of the falls. It sent water into a penstock, which further reduced the amount of water flowing over the falls. The plant first had a capacity of 500 kilowatts (KW). Idaho Power bought the plant in 1916. Over the years, the power plant was expanded and later replaced with newer units that could generate 12,500 KW. Currently, about 950 cubic feet ([convert: unit mismatch])* are needed to run the plant at full capacity. In 2015, Idaho Power announced a plan to increase the capacity to 64,000 KW. This would mean diverting even more water, which would further reduce the water available to flow over the falls.

Evel Knievel's Canyon Jump

On September 8, 1974, American daredevil Evel Knievel tried to jump over the Snake River. This was about 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the falls. He used a rocket-powered motorcycle called the Skycycle X-2. He had tried to get permission from the U.S. Government to jump over the Grand Canyon, but he was not successful. Knievel and his team bought land on both sides of the Snake River. They built a large dirt ramp and launch structure. About 30,000 people came to watch Knievel's jump.

His jump failed because his parachute opened too early. This caused him to float down towards the river. Knievel likely would have drowned if strong canyon winds had not blown him to the river bank. He survived with only a broken nose. In September 2016, professional stuntman Eddie Braun successfully jumped the Snake River Canyon. He used a replica of Knievel's rocket.

Visiting Shoshone Falls Park

As early as 1900, local people wanted Shoshone Falls to become a national park. However, Congress never approved this idea. In 1919, the Shoshone Falls Memorial Park Association suggested creating a memorial park at the falls for World War I veterans. The association hired California landscape architect Florence Yoch to design a plan for the park. But these plans never happened. This was partly because it was hard to get the needed land from its previous owners. Frederick and Martha Adams later bought the land from Senator Clark. They donated it to the City of Twin Falls in 1932. The state of Idaho donated another piece of land in 1933 to add to the park.

Today, Shoshone Falls Park covers the south bank of the Snake River at the falls. There is a $5 fee per vehicle from March 30 through September 30. The park has an overlook, signs with information, and trails along the south rim of the Snake River Canyon. The trails lead to nearby interesting places like Dierkes Lake and the spot where Evel Knievel tried his jump in 1974. About 250,000 to 300,000 vehicles enter the park each year.

In 2015, Idaho Power finished the Shoshone Falls Expansion Project. This project rebuilt parts of the Shoshone Falls Dam to make it look better. It also directed low water releases to the most scenic part of the falls, the "Bridal Veil Falls" on the north bank of the river.

See also

In Spanish: Cascadas Shoshone para niños

In Spanish: Cascadas Shoshone para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |