Snake River facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Snake River |

|

|---|---|

The Tetons and the Snake River (photographed by Ansel Adams, 1942) shows the Snake River and the Teton Range.

|

|

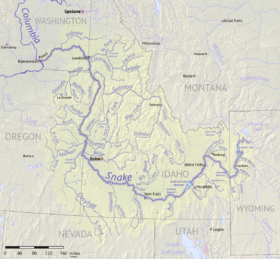

Map of the Snake River watershed

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, Washington |

| Region | Pacific Northwest |

| Cities | Jackson, Wyoming, Idaho Falls, Idaho, Blackfoot, Idaho, American Falls, Idaho, Burley, Idaho, Twin Falls, Idaho, Ontario, Oregon, Lewiston, Idaho, Clarkston, Washington, Tri-Cities, Washington |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Rocky Mountains Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming 9,200 ft (2,800 m) 44°07′49″N 110°13′10″W / 44.13028°N 110.21944°W |

| River mouth | Columbia River at Lake Wallula Burbank, Washington, near the Tri-Cities 341 ft (104 m) 46°11′10″N 119°1′43″W / 46.18611°N 119.02861°W |

| Length | 1,080 mi (1,740 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 107,500 sq mi (278,000 km2) |

| Tributaries |

|

| Type: | Wild 260.8 miles (419.7 km) Scenic 186.4 miles (300.0 km) Recreational 33.8 miles (54.4 km) |

| Reference #: | P.L. 94-199; P.L. 111-11 |

The Snake River is a very important river in the northwestern United States. It is about 1,080 miles (1,740 km) long. It is the biggest river that flows into the Columbia River. The Columbia River is the largest North American river that flows into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake River starts in Yellowstone National Park in western Wyoming. It then flows through the dry Snake River Plain in southern Idaho. Next, it goes through the deep Hells Canyon on the borders of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Finally, it winds through the Palouse Hills in southeast Washington. It joins the Columbia River near the Tri-Cities, Washington.

The area drained by the Snake River, called its watershed, covers parts of six U.S. states. This area is surrounded by the Rocky Mountains to the north and east. To the south is the Great Basin, and to the west are the Blue Mountains. Millions of years ago, volcanoes changed this land. Huge lava flows covered much of the western Snake River watershed. The Snake River Plain itself was formed by the Yellowstone hotspot, a place where hot rock rises from deep inside the Earth. The river was also shaped by huge floods during the last Ice Age. These floods created features like the Snake River Canyon and Shoshone Falls.

Long ago, the Snake River was home to many salmon and other fish that swim from the ocean to fresh water to lay eggs. For thousands of years, fishing for salmon was a big part of the culture and food for indigenous peoples. The Shoshone and Nez Perce were two of the largest tribes living along the river in the early 1800s. In 1805, Lewis and Clark were the first non-natives to see the river. They were looking for a route from the eastern U.S. to the Pacific Ocean. Later, fur trappers explored the area. They hunted beaver so much that the animals almost disappeared.

At first, travelers on the Oregon Trail avoided the dry Snake River region. But after gold was found in the 1860s, many settlers arrived. This led to conflicts with Native American tribes. Eventually, the tribes were moved to reservations. Around 1900, some of the first large irrigation projects in the western U.S. were built along the Snake River. Southern Idaho became known as "Magic Valley" because the desert quickly turned into farmland. Many dams were also built to create electricity. Four dams on the lower part of the river made a shipping channel. This channel allowed ships to reach Lewiston, Idaho, which is the furthest inland seaport on the West Coast.

Building dams and other human activities have greatly reduced the number of salmon and other ocean-going fish. But the Snake River watershed is still important for these fish. The Snake River and its tributary, the Salmon River, have the longest sockeye salmon run in the world. These salmon travel 900 miles (1,400 km) from the Pacific Ocean to Redfish Lake, Idaho. Since the 1950s, governments and private companies have tried hard to help fish populations recover. They have also built fish hatchery programs. There is a big debate in the Pacific Northwest about whether to remove the four lower Snake River dams to help the fish.

Contents

- The River's Journey: Where Does the Snake River Flow?

- The Snake River's Land: What is its Watershed Like?

- How the Snake River Was Formed: A Look at its Geology

- A Look Back: The History of the Snake River

- Shaping the River: Reclamation and Development

- Nature and Challenges: Ecology and Environmental Issues

- Images for kids

- See also

The River's Journey: Where Does the Snake River Flow?

The Snake River starts north of Two Ocean Pass. This is near the southern edge of Yellowstone National Park in the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming. It begins about 9,200 feet (2,800 m) above sea level. The river flows west through the high mountains of the Teton Wilderness. It meets the Lewis River and continues south into Jackson Lake. This is a natural lake in Grand Teton National Park that was made bigger by Jackson Lake Dam. Below the dam, it is joined by Pacific Creek and Buffalo Fork. The river then winds south through the valley of Jackson Hole. This valley sits in front of the Teton Range to the west and the Gros Ventre Range to the east.

Below the town of Jackson, the river forms the Snake River Canyon of Wyoming. It then turns west and flows into Idaho. Here, the Palisades Dam creates Palisades Reservoir. From there, it flows northwest through Swan Valley. It then joins the Henrys Fork near Rexburg. The Henrys Fork is sometimes called the "North Fork" of the Snake River. The part of the main Snake River above where they meet is sometimes called the "South Fork."

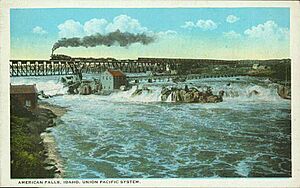

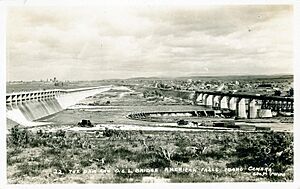

Turning southwest, the river begins its long journey across the Snake River Plain. It passes through Idaho Falls and receives the Blackfoot River from the left. Then it enters the 20-mile (32 km) long American Falls Reservoir, formed by American Falls Dam. From American Falls, it turns west. It flows through Minidoka Dam and Milner Dam. Here, a lot of water is taken out for irrigation. Below Milner Dam, it enters the Snake River Canyon of Idaho. In this canyon, the river gets narrow and forms rapids and waterfalls.

In a 70-mile (110 km) stretch between Milner Dam and the Malad River, the Snake River drops 1,300 feet (400 m). It goes over many waterfalls and rapids. The most famous ones include Caldron Linn, Twin, Shoshone, Pillar, Auger, and Salmon Falls. Idaho Power runs several small power plants along this part of the river. The biggest single drop is the 212-foot (65 m) Shoshone Falls. In the spring, it flows so powerfully that people in the 1800s called it the "Niagara of the West."

The Snake River keeps flowing west. It goes through the C. J. Strike Reservoir, where the Bruneau River joins it from the left. Then it passes through the Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area. After that, it enters farmland on the western side of Idaho's Treasure Valley. It passes about 30 miles (48 km) west of Boise. It briefly crosses into Oregon before turning north to form the border between Oregon and Idaho. Several major rivers join it quickly here. These include the Boise River from the right, the Owyhee and Malheur Rivers from the left. Then the Payette and Weiser Rivers join from the right near Ontario, Oregon. Finally, the Powder and Burnt Rivers join from the left.

Continuing north, the river enters Hells Canyon. This canyon cuts between the Rocky Mountains of Idaho and the Blue Mountains of Oregon and Washington. The Hells Canyon Hydroelectric Complex includes the Brownlee, Oxbow, and Hells Canyon Dams in the upper part of the canyon. Since it was built in 1967, Hells Canyon Dam has been the furthest upstream salmon can travel. In the past, salmon swam as far upriver as Shoshone Falls.

After Hells Canyon Dam, the Snake River rushes northward through the Hells Canyon Wilderness. Most of this river area can only be reached by boat. Its many rapids used to make it very hard to travel by boat. Today, the canyon and the nearby Hells Canyon National Recreation Area are popular for whitewater boating, fishing, and hiking. The Seven Devils Mountains rise up to 8,000 feet (2,400 m) above the river. This makes Hells Canyon one of the deepest canyons in North America, almost one-third deeper than the Grand Canyon. Inside the canyon, the Imnaha River joins from the left. Then its longest tributary, the Salmon River, joins from the right. Further north, it starts to form the Idaho–Washington border. The Grande Ronde River joins from the left. From the end of Hells Canyon at Asotin, Washington, it flows north to Lewiston, Idaho. Here, the Clearwater River, its largest tributary by water volume, joins from the right. The Snake then turns sharply west to enter Washington.

The last part of the Snake River flows through steep valleys in the Palouse Hills of southeast Washington. Near Lyons Ferry State Park, the Tucannon River joins from the left. Then the Palouse River joins from the right. The Palouse River forms Palouse Falls about 8 miles (13 km) upstream from where it meets the Snake. The Lower Snake River Project has four dams with navigation locks. These are Lower Granite, Little Goose, Lower Monumental, and Ice Harbor. These dams have changed the once fast-flowing lower Snake River into a series of lakes. This allows large barges to travel between the Columbia River and the Port of Lewiston. About 10 miles (16 km) downstream from Ice Harbor Dam, the Snake flows into the Columbia River at Burbank, Washington. This is southeast of the Tri-Cities. The rivers meet on Lake Wallula, which is formed by McNary Dam on the Columbia. From there, the Columbia River flows another 325 miles (523 km) west to the Pacific Ocean.

How Much Water Flows in the Snake River?

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has measured the flow rate of the Snake River at Ice Harbor Dam since 1962. The average flow rate for 61 years (1962-2023) was about 49,580 cubic feet per second (1,404 m³/s). The highest flow recorded in one day was 305,000 cubic feet per second (8,600 m³/s) on June 19, 1974. The lowest was 2,000 cubic feet per second (57 m³/s) on November 29, 1961. A huge flood in June 1894 reached an estimated peak of 409,000 cubic feet per second (11,600 m³/s). The Snake River is the twelfth largest river in the United States by flow rate. It provides about one-fifth of the Columbia River's total water that flows into the Pacific.

The Snake River's water level is highest in late spring and early summer. This is when snow melts in the Rocky Mountains. It is lowest in the fall. Even with many dams, its flow into the Columbia changes a lot with the seasons. At Ice Harbor Dam, the average monthly flow is highest in May and June. It is lowest in September and October. The average yearly flow also changes a lot. It was highest in 1965 and lowest in 1997.

In southern Idaho, the Eastern Snake River Plain Aquifer greatly affects the Snake River's flow. This aquifer is one of the largest underground water reserves in the U.S. It is in porous volcanic rock under the plain. It takes in a lot of water from the Snake River in the eastern plain. This water then comes out further west as springs in the Snake River Canyon. Water from "lost streams" (rivers that disappear underground in the eastern plain) also travels through the aquifer to reach the Snake River. Extra irrigation water that soaks into the ground also joins it. Large spring areas at American Falls and Thousand Springs (near Hagerman, Idaho) keep the river flowing steadily even in the driest summers.

The Snake River gets most of its water in the lower one-fourth of its course. By the time it reaches Hells Canyon Dam, its average flow is only about one-third of the flow at its mouth. Two rivers downstream, the Clearwater and Salmon Rivers, add about half of the Snake River's total water.

The Snake River's Land: What is its Watershed Like?

The Snake River watershed covers about 107,500 square miles (278,000 km²). It drains about 87% of Idaho, 18% of Washington, and 17% of Oregon. It also includes small parts of Wyoming, Utah, and Nevada. The eastern edge of the watershed follows the Continental Divide. This is the line that separates rivers flowing to the Pacific from those flowing to the Atlantic. The Snake River watershed is the largest area drained by any river flowing into the Columbia River. It makes up about 40% of the entire Columbia River watershed. The Snake River is about 180 miles (290 km) longer than the Columbia River above where they meet. They drain similar-sized areas, but the Columbia carries more than twice the water.

The Snake River watershed is very mountainous. The northern two-thirds have huge mountain ranges of the Rockies. These include the Salmon River Mountains and the Bitterroot Range. The Blue Mountains form much of the western edge of the watershed. To the south are smaller mountain ranges. To the east are more Rockies ranges, like the Tetons. Gannett Peak, the highest point in the Snake River basin, is in the Wind River Range. It is 13,816 feet (4,211 m) high.

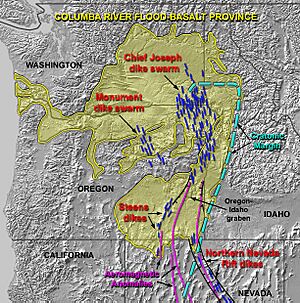

Volcanoes have left many features in the southern part of the watershed. These include lava fields and hot springs. The Columbia River basalts are ancient lava flows that lie under the western part of the watershed. The Snake River Plain is the largest area without mountains. But it still has rough land, with canyons formed by the Snake River and its branches.

Because of the rain shadow effect from the Cascades, there is not much rain. The whole watershed gets about 14 inches (360 mm) of rain on average. Most of the rain falls as snow in the higher mountains. So, most of the water in the Snake River comes from melting snow.

About 50% of the Snake River watershed is dry shrubland and rangeland. The natural plants are mostly sagebrush, with some wheatgrasses. About 30% of the watershed is farmland. Farmers grow potatoes, sugar beets, onions, grains, and alfalfa in the Snake River Plain. In the Palouse Hills, they mainly grow wheat and beans. About 15% of the watershed is forest. These forests have trees like Douglas fir, Engelmann spruce, and lodgepole pine. About 4% of the watershed is barren desert, and only about 1% is city areas.

Most of the Snake River watershed is public land. The U.S. Forest Service manages many national forests here. These forests have many protected wilderness areas. The National Park Service manages places like Craters of the Moon National Monument and Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. Large areas of private farmland are in the Snake River Plain and the Palouse. But most of the Snake River Plain is managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

The Snake River watershed shares borders with other big river systems in North America. To the south, it borders the Great Basin, which includes the area draining to Utah's Great Salt Lake. To the east, it borders the Green River (part of the Colorado River system) and the Yellowstone and upper Missouri Rivers (part of the Mississippi River system). To the north, it borders the Clark Fork and Spokane Rivers, which are also part of the Columbia River system. To the northwest, it borders other rivers that flow into the Columbia, like the John Day and Umatilla Rivers.

How the Snake River Was Formed: A Look at its Geology

The Snake River's path today was formed over millions of years. It was once made up of several separate river systems. Much of the Pacific Northwest was under shallow seas until about 60 million years ago (Ma). The Columbia River's path to the Pacific was set about 40 Ma. By about 17 Ma, the "Salmon-Clearwater River" (the modern lower Snake River) flowed west into the Columbia.

Then, the Columbia River basalts erupted. These were huge lava flows that covered vast areas. They changed the landscape and hid most of the old river channels starting about 17 Ma. The first lava flows pushed the ancient Salmon-Clearwater River much further north than it is today.

Around 12–10 Ma, the Blue Mountains region began to rise. This lifted the lava layers to form a plateau. From about 11–9 Ma, the western half of the Snake River Plain sank. This created a valley between fault lines. The old Snake River's path was blocked, and water collected to form the huge Lake Idaho around 10 Ma. The eastern half of the Snake River Plain formed as the North American Plate moved west over the Yellowstone hotspot. Hot rock rising from below caused the land to lift, forming highlands like the Yellowstone plateau today. As the hotspot moved east, the land behind it sank, creating the low area of the eastern Snake River Plain.

This eastward movement of the hotspot pushed the Continental Divide to the east. Before the eastern Snake River Plain formed, the area east of Arco, Idaho (the modern headwaters of the Snake River) flowed towards the Atlantic Ocean. The moving Continental Divide made the land slope west. So, water flowed west into Lake Idaho. The Snake River Plain's drainage system kept growing east, towards what is now Yellowstone National Park. During this time, the Snake also captured the Bear River. The Bear River was later rerouted towards the Great Salt Lake about 50,000 or 60,000 years ago by lava flows.

About 2.5 Ma, Lake Idaho reached its highest level. It then overflowed northward into the Salmon-Clearwater river system near Huntington, Oregon. Over about two million years, this overflow carved Hells Canyon. This emptied Lake Idaho and connected the upper Snake and Salmon-Clearwater into one river system.

The Teton Range, a key feature of the Snake River's headwaters, began to rise about 10 Ma. About 2 Ma, the Hoback Fault formed east of the Tetons. A valley formed between the faults, creating Jackson Hole. As the valley sank, water filled it to create Lake Teewinot. This lake drained east into the Green River–Colorado River system. About 1 Ma, the Snake River captured the Jackson Hole watershed. This drained Lake Teewinot and finally connected the modern Snake headwaters to the rest of the river. This area was shaped by several Ice Age glaciations. These glaciations carved the Tetons and created lakes like Jackson Lake.

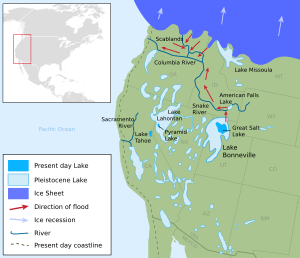

The Snake River's path beyond Jackson Hole was not directly affected by glaciers. But its landscape was greatly changed by Ice Age floods. About 15,000 years ago, the edge of Red Rock Pass south of Pocatello, Idaho broke. This released a huge amount of water from Lake Bonneville into the Snake River Plain. The flood was about 500 times bigger than the largest recorded flood of the Snake at Idaho Falls today. This flood completely changed the Snake River Plain. It created the Snake River Canyon, its waterfalls, and huge fields of boulders. The floodwaters then flowed through Hells Canyon. However, most signs of their effects on the lower Snake River were erased by the much larger Missoula Floods. These floods happened at the same time and covered the Columbia Basin. They were caused by an ice dam in western Montana repeatedly breaking. Dozens of floods overflowed into the lower Snake River from the north. They backed up water as far upstream as Lewiston. The Palouse River, which used to flow west, was rerouted to flow south into the Snake River. This formed Palouse Falls, whose large plunge pool shows the power of the floods.

A Look Back: The History of the Snake River

First Peoples Along the River

Around the end of the last Ice Age, the Snake River Plain was home to hunter-gatherers. These included people from the ancient Clovis, Folsom, and Plano groups. Along the lower Snake River in Washington, the Marmes Rockshelter shows signs of people living there continuously from about 9000 BCE until about 1300 CE. Around 2200 BCE, people in the western Snake River basin started living in one place for longer periods. They relied more on fish (especially salmon) and learned to preserve and store food. Shoshoni-speaking people arrived in the Snake River Plain between 600 and 1500 CE.

When Europeans first arrived, several Native American tribes lived in the Snake River watershed. The Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) lived in north-central Idaho, southeast Washington, and northeast Oregon. This included much of the lower Snake River below Hells Canyon. The Northern Shoshone and the Bannock lived from the Snake River Plain east to the Rocky Mountains. A Nez Perce name for the river was Kimooenim, meaning "the stream/place of the hemp weed." Another Nez Perce name was Pikúunen. The Wanapum and Walla Walla people called the lower Snake River Naxíyam Wána. The Shoshone called the river Yampapah, after the yampah plant that grew along its banks.

Downstream of Shoshone Falls, salmon and steelhead trout were a key food source for native peoples. These fish spend their adult lives in the ocean and return to fresh water to lay eggs. They were also very important culturally. Tribes held rituals like the first salmon ceremony. They also had strict rules about how many fish could be caught. This made sure enough salmon survived to lay eggs. The Nez Perce had more than seventy permanent villages near their fishing grounds on the Snake, Clearwater, and Salmon Rivers. Families gathered at fishing sites starting in May or June. Fishing moved to higher streams throughout the summer. Fall-run fish were saved for winter.

Shoshones in the western Snake River Plain also relied heavily on salmon. At Shoshone Falls and other waterfalls, they used fishing platforms, spears, baskets, and traps. In 1832, Captain Benjamin Bonneville saw that "Indians at Salmon Falls on the Snake River took several thousand salmon in one afternoon by means of spears." East of the falls, many Shoshone and Bannock lived in nomadic groups. They traveled to the falls during the spring salmon run. Then they gathered camas bulbs and hunted bison through the summer and fall.

Hells Canyon on the Snake River was a natural border between the Nez Perce and Shoshone, who were often enemies. Both tribes got horses in the late 1600s or early 1700s. This allowed them to trade and hunt over long distances. With horses, the Nez Perce could travel east of the Bitterroot Mountains to hunt bison. They used a trail over Lolo Pass. The Lewis and Clark expedition later followed this trail to reach the Snake and Columbia Rivers.

Why is it Called the Snake River?

The river's modern name comes from a misunderstanding. The Plains Indians called the Shoshone people "Snake People." The Shoshone are believed to have called themselves "People of the River of Many Fish." However, the Shoshone sign for "salmon" was similar to the Plains Indian sign for "snake." The English name for the river likely came from this interpretation of the hand gesture.

Early Explorers and Fur Traders

The first Europeans to reach the Snake River watershed were the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In August 1805, they crossed the Continental Divide and came down to the Salmon River. They named it "Lewis's River." The river's rapids stopped them, so they crossed the Bitterroot Mountains using a Nez Perce trail. After paddling down the Clearwater River, they reached the Snake River on October 10, 1805. They learned the Nez Perce name for it was Kimooenim. Six days later, they reached where the Snake and Columbia Rivers meet. The expedition made friends with the Nez Perce.

Other explorers soon followed, many of them fur trappers. John Colter, a former member of Lewis and Clark's group, explored the Jackson Hole area in 1808. In 1810, Andrew Henry explored and named the Henrys Fork of the Snake River. He built Fort Henry, the first American fur trading post west of the Rocky Mountains. But he left it after a harsh winter. The 1811 Pacific Fur Company expedition tried to find a route from Henrys Fork to the Columbia River. After their boat crashed in the Snake River Canyon, they traveled overland through the Snake River Plain. They crossed the Blue Mountains to avoid Hells Canyon and reach the lower Snake River. After this dangerous trip, the leader, Wilson Price Hunt, called it "Mad River." A group led by Robert Stuart returned east across the plain the next year. The route they mapped later became part of the Oregon Trail.

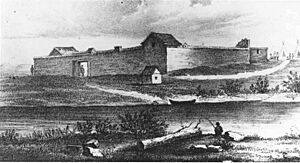

In 1818, Donald Mackenzie and Alexander Ross built Fort Nez Percés for the North West Company near where the Snake and Columbia Rivers meet. The next year, Mackenzie traveled up the Snake River and reached Boise Valley. He was the first to travel up Hells Canyon by river. Mackenzie wanted to avoid the hard trip over the Blue Mountains. He wrote that traveling by water was "safe and practicable for loaded boats."

Canadian fur trappers from the British Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) arrived in the Snake River watershed in 1819. As American fur trappers came to the region, the HBC told the Canadians to kill as many beavers as they could. Their idea was that "if there are no beavers, there will be no reason for the Yanks to come." This "fur desert" policy was carried out in nine trips from about 1824–1831. It aimed to reduce American interest in the Oregon Country. By the time the Americans took over Oregon Territory in 1848, beavers were almost gone from much of the Rocky Mountains.

Starting in the 1840s, the Oregon Trail became well-known. Thousands of settlers passed through the Snake River Plain on their way to the Willamette Valley. The Oregon Trail reached the Snake River at Fort Hall, Idaho. It stayed south of the river until Three Island Crossing. Here, the trail split. The northern route crossed the river to reach the HBC trading post at Fort Boise. The southern route continued into eastern Oregon. The northern route was better, but crossing the Snake River was very hard. During high water, many travelers had to take the hot, dry southern route or risk drowning. Travelers going through Fort Boise had to cross the river one more time. A ferry existed at Fort Boise since at least 1843. The Three Island crossing also got a ferry in 1869. A new wave of travelers came in the 1860s with the Montana Trail. This trail led to gold discoveries in Montana. It crossed the Snake River by the Eagle Rock Ferry and later a bridge. The city of Idaho Falls soon grew around this bridge.

Settlement and Conflict: The Snake River's Changing Landscape

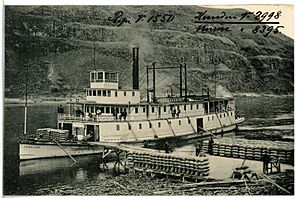

As more settlers arrived, the Nez Perce and their neighbors were pressured to give up parts of their land. Tensions grew in 1855 after tribes were forced to give up huge amounts of land in the Treaty of Walla Walla. In 1859, a force led by Col. George Wright entered the lower Snake River country. They built Fort Taylor and fought the natives, killing their horses and destroying food. The steamboat Colonel Wright was used to bring supplies up the Snake River to Fort Taylor. It was the first steamboat to travel on the Snake River.

Two years later, gold was discovered on Nez Perce land. Thousands of people rushed to the area. The city of Lewiston was founded in 1861, which broke the 1855 treaty. The U.S. government sided with the settlers. They pressured some Nez Perce leaders to sign a new treaty that made their reservation 90% smaller. Many Nez Perce, including Chief Joseph's group, refused to leave. They called the new treaty the "thief treaty." In March 1863, Idaho Territory was created, and Lewiston became its capital. More than 60,000 gold seekers came to the Lewiston Valley by 1863. Many new steamboats were used. The river's rapids made travel difficult, and from November to April, the river was often too low for ships. Still, transporting goods and people by water was very profitable.

Upriver, the Shoshone and other tribes also became worried about settlers. In 1854, a Shoshone group attacked a wagon train. The U.S. Army fought back. The situation became so bad that Fort Boise was abandoned. The Army had to escort wagon trains through the area. While early settlers just passed through, gold discoveries brought new interest in the 1860s. The Army rebuilt Fort Boise in 1863. A military group was stationed there to stop violence. But tensions kept growing, and more wagon trains were attacked. Starting in 1864, the Snake War was fought across much of southern Idaho. There were many battles between the U.S. Army and the Shoshone, Bannock, and Paiute. By 1868, after years of fighting, Chief Pocatello and many others surrendered. They moved to the Fort Hall Indian Reservation on the Snake River in southeast Idaho.

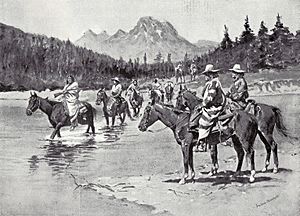

Tribal resistance continued for years. In 1877, the U.S. government tried to force the remaining Nez Perce onto their reservation. Chief Joseph's group and others decided to seek safety elsewhere. After a dangerous crossing of the Snake at Dug Bar, Hells Canyon, the Nez Perce were chased by the Army for over 1,000 miles (1,600 km). They fought several battles. On October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph surrendered, ending the Nez Perce War. The survivors were sent to different reservations. In 1878, an uprising happened because of overcrowding and food shortages at the Fort Hall Reservation. This led to the Bannock War. The U.S. Army defeated the Bannock and restricted travel in and out of the reservation.

While Lewiston was connected by river, travel to Boise and other places upriver on the Snake River remained hard due to Hells Canyon. In 1865, Thomas Stump tried to pilot the Colonel Wright up Hells Canyon. He made it 80 miles (130 km) upriver before hitting rocks and having to turn back. On the Snake River above Hells Canyon, several steamboats were built. The first was the Shoshone in 1866. However, running the upper Snake was not profitable. The owners of Shoshone decided to move her to the lower Snake River. In April 1870, they made the first successful trip down Hells Canyon. It was a very dangerous ride. In 1895, the steamboat Norma also made the trip.

In the 1870s, Boise (Idaho's capital since 1866) grew quickly. Gold brought more than 25,000 gold seekers to the Boise Valley. A new city quickly grew around the U.S. Army post at Fort Boise. Since Hells Canyon was not good for river travel, people wanted to connect the area by train. By 1884, the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company (later part of Union Pacific) connected Portland, Oregon, to the Union Pacific line in Wyoming. Boise was connected three years later. Besides trade, the railroad also opened the Snake River region to tourism. The Union Pacific promoted places like Shoshone Falls. A brochure described Shoshone Falls: "Shoshone differs from every other waterfall in this or the old country. It is its lonely grandeur that impresses one so deeply."

Shaping the River: Reclamation and Development

Farming and Water Use

Most travelers on the Oregon Trail saw the dry Snake River Plain as something to cross, not a place to settle. This changed with the gold discoveries in Boise. The demand from mining and the difficulty of bringing in goods led to a farming boom in the Boise Valley. By the 1880s, settlers also came to the upper Snake River north of Idaho Falls. The rich, sandy soils there were perfect for growing the famous russet potato ("Idaho potato"). The dry climate meant irrigation was needed. Many private irrigation companies were formed. They built canals around Boise and Idaho Falls, which worked well. But all the easy-to-farm land was soon used up. These companies could not afford to expand further or build dams to store water.

Many private irrigation companies were struggling. So, the federal government began to help with farming development. The 1894 Carey Act gave large areas of dry federal land to western states. The states then sold the land to farmers and asked private investors to create irrigation districts. Investors would make their money back by selling water rights to farmers. Engineers reviewed irrigation plans to see if they would be profitable. The Carey Act was not very successful in most states, but it greatly helped Idaho. About 60% of all land developed under this act was in Idaho, and almost all of it used Snake River water.

I. B. Perrine, who settled near Shoshone Falls in the 1880s, created one of the most successful projects. In 1900, Perrine claimed water from the Snake River. With a lot of private money, he oversaw the building of Milner Dam and a canal system. This system irrigated about 250,000 acres (1,000 km²) of the Snake River Plain. Completed in 1905, the project was an instant success. The quick change from barren land to productive farmland led to the nickname "Magic Valley". It also led to huge growth for the city of Twin Falls. At certain times of the year, almost all the Snake River's water was diverted at Milner Dam. Since then, Shoshone Falls often runs dry in the summer.

With the creation of the Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation) in 1902, the federal government became more involved in water development. The large Minidoka Project was the first federal project in Idaho. It started with Minidoka Dam in 1906. Over the next few decades, it grew to include major reservoirs at Jackson Lake, American Falls, and Island Park. It also had a large network of canals and pump stations. The Minidoka Project eventually brought water to a million acres (4,000 km²) of the Magic Valley. During World War II, many Japanese Americans interned at Minidoka were made to work on the project. The Boise Project, which would water 500,000 acres (2,000 km²) in and around the Boise Valley, was another big early project. When it was finished, Arrowrock Dam (1915) on the Boise River was the tallest dam in the world. Its building process was an important example for future federal projects like Hoover Dam.

Around the 1950s, farmers started using the Snake River aquifer a lot. This brought large new areas into production. Surface water development also increased with projects like Cascade Dam (1948) and Anderson Ranch Dam (1950). These provided more water storage for the Boise Project. Palisades Dam was built in 1956. It provided flood control and irrigation for the Snake River above Idaho Falls. Near Rexburg, the Teton Dam was also built to provide water for this area. In 1976, the Teton Dam failed completely. It killed eleven people and caused at least $400 million in damage. This disaster led to the end of large new irrigation projects for the Snake River system and for the Bureau of Reclamation.

Farming has greatly affected the water quality in the Snake River upstream of Hells Canyon. Water taken from the river for irrigation gets dirty with chemical fertilizers and animal waste. This water then soaks into the Snake River Aquifer. Pollutants collect in the groundwater and eventually enter the river through springs. Too much nitrogen, phosphorus, and bacteria are found in many places across southern Idaho. Large algae blooms are a common problem in summer. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has set rules for the quality of Snake River water entering Hells Canyon. These rules cover bacteria, mercury, nutrients, pesticides, and water temperature. To follow these rules, farmers and foresters use best management practices. Water quality is also checked regularly.

Making Electricity: Hydroelectric Power

Power development on the Snake River began in the early 1900s. Cities, farms, mines, and industries were growing. The first small hydroelectric plant on the Snake River, Swan Falls Dam, was built in 1901. Another was built at American Falls in 1902. Many other projects followed, especially around Shoshone Falls. The natural drop of the river there offered great potential for energy. After building the Milner Dam irrigation system, I. B. Perrine built a hydroelectric plant at Shoshone Falls in 1907. Small private companies built power plants at Salmon Falls (1910) and Thousand Springs (1912). Idaho Power was formed in 1915 and bought all these plants the next year. It then built a second, larger plant at Shoshone Falls in 1921, and another at Twin Falls in 1935. Electric pumps allowed farming in new areas where water could not flow by gravity before. The Minidoka Project, which included the Bureau of Reclamation's first hydroelectric plant in Idaho, was an early user of this system. The project made more power than it needed. The extra power was sold to nearby towns like Burley and Rupert.

By the 1940s, after huge dams like Grand Coulee were built on the Columbia River, people looked at the Snake River's power potential in Hells Canyon. In 1947, Idaho Power planned three medium-sized dams in the upper canyon. Two years later, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Army Corps) suggested one huge dam, over 700 feet (210 m) high, in lower Hells Canyon. In 1955, the Federal Power Commission approved Idaho Power's project. But at first, only one of the three dams, Brownlee (finished 1958), was built.

Another company proposed the "High Mountain Sheep Dam" on the Snake River. The "Nez Perce Dam" was even bigger. It was proposed by the Washington Public Power Supply System. This dam would have made more power, but it would have destroyed the valuable salmon fishery in the Salmon River. In 1964, the Commission chose the High Mountain Sheep project. By then, many people were against the high dam. They argued it would still block salmon migration and harm wildlife in Hells Canyon.

The case went to the Supreme Court. In 1967, the court stopped the project temporarily. Justice William O. Douglas wrote that when approving projects, the Commission must think about "future power demand and supply, alternate sources of power, the public interest in preserving reaches of wild rivers and wilderness areas, the preservation of anadromous fish for commercial and recreational purposes, and the protection of wildlife." This was the first time the court said protecting the environment was important for approving a dam. In 1975, President Gerald R. Ford signed the Hells Canyon Wilderness into law. This ended the high dam project for good.

Meanwhile, Idaho Power went ahead with the Oxbow and Hells Canyon Dams. But the problem of fish passage remained. From 1956 to 1964, adult salmon returning to lay eggs were caught at Brownlee Dam (which was too high for a fish ladder) and released upstream. Getting young salmon downstream was a bigger problem. Many died going through the power turbines. In 1960, Idaho Power suggested stopping fish passage and building fish hatcheries instead. By 1966, they agreed with the Federal Power Commission to do this. By 1967, both Oxbow and Hells Canyon dams were finished without fish passage. Idaho Power was in charge of building and running several fish hatcheries.

As of 2007, the Hells Canyon Hydroelectric Complex made 40% of Idaho Power's total electricity. The three dams produce about 6,053 gigawatt hours per year. Idaho Power's hatcheries release almost seven million young salmon and steelhead into the Snake River system each year. Since the Hells Canyon complex was finished, only one major hydroelectric dam has been built in the Snake River system. This was the Army Corps' Dworshak Dam (1973) in the Clearwater River basin. Like the Hells Canyon dams, Dworshak also caused arguments about its effect on fish. It also had no fish passage, but a hatchery was built at the dam's base.

As gold mining decreased in the late 1800s, the wheat industry grew in the Palouse of southeast Washington. By the 1870s, the Oregon Steam Navigation Company used seven steamboats to carry grain from the Snake River to ports on the lower Columbia River. In the 1890s, a huge copper deposit was found in Hells Canyon. Several ships carried ore from there to Lewiston. In 1893, the Annie Faxon steamboat exploded and sank below Lewiston, killing five people. Starting in the 1880s, the Army Corps began digging out the Snake River below Lewiston to keep a 5-foot (1.5 m) deep channel for boats.

River traffic quickly decreased once railroads arrived. By 1899, the Union Pacific line along the south bank of the Snake River reached Riparia, Washington. It then joined with the Northern Pacific Railroad to build the Camas Prairie Railroad to Lewiston, which it reached in 1908. The Open River Transportation Company, which ran steamboats between Lewiston and Celilo Falls on the Columbia, went out of business in 1912. The completion of the Celilo Canal in 1915 made it easier for boats from the upper Columbia and Snake to reach Portland. But steamboats could not compete with railroads in speed and efficiency. The last steamboat on the lower Snake ran in 1920.

Once railroads had a monopoly on grain shipments, they raised shipping rates. This made farmers upset. In 1934, Herbert G. West organized the Inland Empire Waterways Association (IEWA). This group wanted an "open river" – a deep shipping channel on the Snake and Columbia Rivers. This channel could compete with trains. The IEWA first pushed for bigger locks at Bonneville Dam in 1938 and the building of McNary Dam on the Columbia. These would improve travel to the mouth of the Snake. In 1941, a bill was introduced in Congress to let the Army Corps develop the lower Snake River. This bill failed. But after several years of debate, Congress finally approved the Snake River development in 1945. Early plans included six to ten small dams for the lower Snake. This was later reduced to four bigger dams. These dams would need the tallest navigation locks in the world at the time, over 100 feet (30 m) high.

Tribes, state wildlife agencies, and the fishing industry were against the dams. They argued the dams would kill too many salmon. In 1947, the U.S. Department of the Interior suggested a ten-year pause on dam building to study the fish problem. With the start of the Cold War, the need for electricity in the Pacific Northwest grew. So, the project's focus shifted to hydropower. By 1948, the Army Corps estimated that over 80% of the economic benefits would come from power, and only 15% from navigation. Dam opponents argued that if power was the main goal, other dam sites existed that would harm fish less. But these arguments failed, as the lower Snake River dams were already approved. Washington Senator Warren G. Magnuson pushed through a budget change in 1955 to start building the first dam, Ice Harbor.

Once construction began in 1956, Congress quickly approved more money to finish the project. Ice Harbor Dam was completed in 1962. Lower Monumental and Little Goose Dams were completed in 1969 and 1970. The Lower Monumental project caused controversy because it threatened to flood the Marmes Rockshelter archaeological site. Although the Army Corps agreed to build a dike around the site, it began to leak as the reservoir filled, and the site was flooded. By the 1970s, the environmental movement in the U.S. had grown much larger. Groups like the Association of Northwest Steelheaders tried to stop the building of the fourth dam, Lower Granite. These efforts were not successful, and the dam was completed in 1975. The first barge reached Lewiston on April 10 of that year. The Army Corps had planned one more dam at Asotin. This would have extended navigation to mines upstream of Lewiston. But facing public opposition, Congress stopped the project in 1975.

Once the dams were finished, barges up to 12,000 tons could reach Lewiston. Today, several barge terminals operate along the lower Snake. Grain makes up most of the barge traffic. Other shipments include wood products, fuel, and fertilizers. In 2020, a total of 4.2 million tons of cargo were barged on the Snake River. Since 2000, the amount of commercial shipping on the Snake River has decreased. This is mostly because a pipeline was built for petroleum products. After the Great Recession, other types of cargo have been slow to recover. As of 2015, grain tonnage had fallen by about a third from 2000 levels. Wood products had fallen by nearly three-quarters, with many shipments switching back to rail. Container shipping at the Port of Lewiston stopped in 2015. From 2015 to 2023, grain exports from the Port of Lewiston have stayed about the same.

As dam opponents feared, Snake River salmon numbers dropped greatly after the dams were built. Since 2000, there have been new calls for removing the lower Snake River dams. This has become a big political issue for the Pacific Northwest.

Nature and Challenges: Ecology and Environmental Issues

Water Homes: Aquatic Habitats

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) divides the Snake River into two freshwater ecoregions: the Upper Snake and Columbia Unglaciated. Shoshone Falls marks the border between them. Shoshone Falls has stopped fish from moving upstream for at least 15,000 years. The Big Wood River is also in the Upper Snake ecoregion because it has its own natural waterfall barrier. As a result, only 35% of the fish species above Shoshone Falls are also found in the lower Snake River.

Compared to the lower Snake River, the Upper Snake ecoregion has many unique species. This is especially true for freshwater molluscs like snails and clams. At least 21 snail and clam species are of special concern. There are 14 fish species in the Upper Snake region that are not found anywhere else in the Columbia's watershed. But they are found in some western Utah watersheds and the Yellowstone River. These include healthy numbers of Yellowstone cutthroat trout and Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout. The Wood River sculpin lives only in the Wood River. The Shoshone sculpin lives only in the small part of the Snake River between Shoshone Falls and the Wood River.

The Snake River below Shoshone Falls is home to about 35 native fish species. Twelve of these are also found in the Columbia River. Four are unique to the Snake or nearby areas: the sand roller, shorthead sculpin, margined sculpin, and the Oregon chub. Bull trout travel from the main Snake River to lay eggs in several tributary basins, including the Bruneau, Imnaha, and Grande Ronde Rivers. Large white sturgeon, introduced in the 1800s, were once common below Shoshone Falls. Because of dam building, only a few groups remain. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game has sometimes recorded sturgeon over 10 feet (3 m) long in Hells Canyon. Other common fish that have been introduced include whitefish, pikeminnow, smallmouth bass, and rainbow, brown, brook, and lake trout.

Salmon and Steelhead: Anadromous Fish Life Cycle

Anadromous salmonids (Oncorhynchus), like chinook, coho, and sockeye salmon, and redband and steelhead trout, were historically the most common fish. They were a keystone species (meaning they are very important to the ecosystem) in the Snake River system. Before the 1800s, between two and six million adult salmon and steelhead returned each year from the Pacific Ocean to lay eggs in the Snake River watershed. Salmon die after laying eggs. Their bodies provide important nutrients to mountain rivers that do not have many natural food sources. Rivers below Hells Canyon, especially the Salmon River, had the best places for laying eggs. Many fish also made it above Hells Canyon as far as Shoshone Falls. The Snake River produced about 40% of all chinook salmon and 50% of all steelhead in the Columbia River watershed.

The number of anadromous fish began to drop in the late 1800s. This was due to commercial fishing, logging, mining, and farming. But even in the 1930s, 500,000 fall chinook salmon returned each year. Fish numbers dropped even more once dams were built on the lower Snake and Columbia Rivers. Hells Canyon Dam blocked access to the upper Snake. Wild Snake River spring and summer chinook returns fell from 130,000 in the 1950s to less than 5,000 in the 1990s. Wild steelhead returns followed a similar pattern, falling from 110,000 in the 1960s to less than 10,000 in the 1990s. Spring, summer, and fall-run chinook were all listed as threatened in 1992. Snake River steelhead were also listed as threatened in 1997.

Wild chinook salmon and steelhead numbers continued to drop into the 1990s. But they have started to recover since 2000. In some years, both chinook and steelhead returns have been up to 20,000–30,000. Coho salmon had disappeared from the Snake River by the 1980s. They were brought back to the watershed in 1995.

Snake River sockeye salmon once numbered up to 150,000 adults. Between 24,000 and 30,000 sockeye returned to Wallowa Lake, but this group was gone by 1905 due to too much fishing and irrigation diversions. The Payette Lake population, once up to 100,000, was blocked by the Black Canyon Dam in 1924. Sockeye in the Sawtooth basin were wiped out by actions of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game in the 1950s. Snake River sockeye returns fell to 4,500 in the 1950s and only a few dozen by the late 1960s. Snake River sockeye were listed as endangered in 1991.

Many hatcheries are run by groups like the Army Corps and Idaho Power. They release about 33 million young salmon and steelhead into the Snake River watershed each year. However, the survival rate for hatchery fish is low. Only 0.4% of hatchery chinook and 1.5% of hatchery steelhead returned as adults between 2007 and 2016.

Upstream of the four lower dams, the Snake River watershed has some of the best remaining places for fish to lay eggs in the Columbia River system. This is especially true along the Clearwater and Salmon Rivers. The Salmon River is one of the longest undammed rivers in the continental U.S. A much smaller sockeye salmon group still lays eggs in Redfish Lake near Stanley, Idaho. This is more than 900 miles (1,400 km) inland from the Pacific Ocean. This is the southernmost, highest elevation, and longest sockeye run in the world.

Land and Water: Terrestrial and Wetland Habitats

The Snake River provides important habitat for wildlife along most of its path. This is especially true in the dry Snake River Plain, where it is the only water source for many miles. The upper parts of the Snake River, including Jackson Hole and the floodplain north of Idaho Falls, have large riparian forests. These forests are mostly made up of black cottonwood and narrowleaf cottonwood. The Northwest Power and Conservation Council says these are "some of the most important cottonwood gallery forests in the Intermountain West." Seasonal floods clean and change the shoreline. They clear out older trees and make room for new growth. A rare orchid, Ute lady's tresses, is found in wetlands along with willows and other plants.

The Fort Hall Bottoms in the southern Snake River Plain are an important wetland along the river. They are a major wintering and nesting site for waterfowl, shorebirds, and birds of prey, including bald eagles and trumpeter swans. Part of these wetlands were flooded when American Falls Dam was built. Large parts of the rest have been damaged by cattle grazing. Ponds and wetlands in the Hagerman Valley, near the Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, are also used a lot by migratory and resident birds. South of Boise, the nearly 500,000-acre (2,000 km²) Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area has the most nesting birds of prey in the U.S.

The Snake River headwaters are part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The National Park Service calls this "one of the largest nearly intact temperate-zone ecosystems on Earth." This area is home to some of the largest wild elk and bison populations in the U.S. It also provides habitat for grizzly bears, wolverines, and lynx. Another major wild area in the Snake River watershed is Idaho's very rugged Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness. This is the largest federally protected wilderness in the connected U.S. Although the Snake River watershed is not heavily populated, most of its landscape has been greatly changed by humans since the 1800s. Heavy logging has happened in the Boise area and on the Clearwater River. Logging is still a big industry in the region. Large areas of native sagebrush-steppe ecosystems, mostly in the Snake River Plain and Palouse, have been turned into farmland. About two-thirds of the Snake River Plain is still grassland or shrubland. However, much of this land is affected by livestock grazing. Fires have also become more severe with the spread of invasive plants like cheatgrass.

A Big Debate: Should Dams Be Removed?

The lower Snake River dams have been a source of debate since they were built. In the 21st century, there has been more discussion about possibly removing them. Even though the dams have fish ladders, the warm, slow-moving water in the reservoirs confused migrating fish. Young fish also died trying to pass through the dams. In 1980, Congress passed the Northwest Power Act. This law requires federal agencies in the Northwest to lessen the impact of their dams on fish and wildlife. Fish screens and bypasses have helped young fish survive. But efforts to catch fish and move them around the dams have not been very successful. Although wild salmon and steelhead numbers have improved since the 1990s, they are still much lower than before the dams.

People who support dam removal include tribal groups like the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and environmental groups like the Natural Resources Defense Council. They argue that the cheapest way to bring back the fish is to remove the dams. They say it is better than spending a lot of money on recovery efforts that are not working well. As of 2023, over $17 billion had been spent on Snake River salmon recovery and hatchery operations. There are other economic reasons for dam removal. For example, the yearly cost of keeping the barge channel open is more than the money made from shipping. Also, goods can be moved by train instead. The dams only produce a small amount of the total hydropower in the Northwest. A study by the University of Idaho estimated that over 20 years, removing the dams would be cheaper than continuing fish recovery efforts with the dams in place. Representative Mike Simpson (R-ID) is a big supporter of dam removal. In 2021, he proposed a plan to remove the dams.

People who are against dam removal include farmers, local governments like Lewiston, and the Bonneville Power Administration. They say that even though river traffic has decreased, it is still important to the area's economy. Moving cargo by barge is cheaper and uses less fuel than diesel trains. While the dams do not make a lot of constant power, they are important for managing peak electricity demand. Hydropower can be quickly increased or decreased. As more wind and solar energy are added to the Northwest power grid, more balancing will be needed. Washington governor Jay Inslee and Washington Senator Patty Murray have said they might support dam removal. But they stressed that hydropower must be replaced by other renewable sources. They also said that economic impacts, like losing the ship channel, should be "mitigated or replaced."

In December 2023, the Biden administration supported the Columbia Basin Restoration Initiative. This plan would find ways to replace the power and navigation benefits from the Snake River dams. It would also explore options for restoring the river after dam removal. This initiative is an agreement between the federal government, four tribal nations, Washington and Oregon states, and several conservation groups. It would not directly approve dam removal, which would need a separate law from Congress.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Río Snake para niños

In Spanish: Río Snake para niños

- List of crossings of the Snake River

- List of tributaries of the Columbia River

- List of rivers of Idaho

- List of rivers of Oregon

- List of rivers of Washington (state)

- List of rivers of Wyoming

- List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem)

- List of longest streams of Idaho

- List of longest streams of Oregon

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |