Bannock War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bannock War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Bannock Shoshone Paiute |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Buffalo Horn Egan |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 900+ | 600-800 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12–15 | 7–15 | ||||||

The Bannock War of 1878 was a conflict between the U.S. military and Native American warriors. It involved the Bannock and Paiute tribes in Idaho and northeastern Oregon. The fighting took place from June to August 1878.

The Bannock tribe had about 600 to 800 people in 1870. Their leader was Chief Buffalo Horn. He was killed in battle on June 8, 1878. After his death, Chief Egan took over leadership. He and some of his warriors were killed in July by a group of Umatilla warriors.

The U.S. military was led by Brigadier General Oliver O. Howard. Soldiers from the 21st Infantry Regiment and volunteers fought in the war. Other states also sent their own militias to help. The war ended in August and September 1878. The remaining Bannock and Paiute forces surrendered. Many returned to the Fort Hall Reservation. The U.S. Army forced about 543 Paiute and Bannock prisoners to move to the Yakama Indian Reservation in southeastern Washington Territory.

Contents

Why the War Started

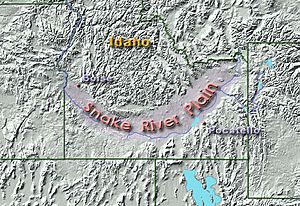

The Bannock people developed as a separate group from the Northern Paiute. In the 1700s, some Paiutes moved to the Snake River plain in Idaho. They wanted to join with the Shoshone people, who spoke a similar language and rode horses. These Paiutes became known as the Bannock.

The Bannock quickly adopted the Shoshone way of life. They rode horses and married into Shoshone families. The Bannone helped the Shoshone. Many Shoshone had died from diseases brought by Europeans.

Europeans Arrive

When the American Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived in Idaho in 1805, the Bannock-Shoshone were already trading. They traded with the Hudson's Bay Company and North West Company from Canada. They soon began trading with Americans for guns and horses.

The Shoshone-Bannock remained independent. They took part in the Rocky Mountain fur trade, which ended around 1840. After this, things changed. More European-Americans began moving into the Snake Valley plain in the 1850s. They were looking for gold in places like Boise and Montana. These new settlers competed for hunting grounds and water. By the mid-1860s, many settlers lived in the Snake region. This greatly affected the Shoshone-Bannock people.

The arrival of European-Americans changed the Shoshone-Bannock way of life. Their traditional customs and seasonal practices were challenged. New ways of farming and raising animals replaced their old ways of getting food. They started to rely more on European-American goods and methods.

American leaders wanted to buy land from the Shoshone-Bannock. In the 1860s, they began trading goods for land titles in the Snake River Plains. This brought even more settlers to the Idaho territory, especially near Boise. In 1866, Governor Lyon created a camp for some Bannock near Boise City. This was to protect them from fearful settlers. The camp did not have enough food or supplies. The Shoshone-Bannock had to depend on settlers for work and food. Many asked for their own reservation land.

Moving to eastern Idaho was a big challenge for the Shoshone-Bannock. Their culture and religion were tied to the land in the Snake Valley. They believed their ancestors' spirits lived there. After much discussion, the Shoshone-Bannock leaders agreed to move to the Fort Hall Reservation. They finished moving in 1869.

Life at Fort Hall Reservation

The Fort Hall Reservation was a large area of land. It was about 1.8 million acres along the Upper Snake River in eastern Idaho. The land could be used for farming. However, the Shoshone-Bannock faced problems right away. They depended on native foods and buffalo found outside the reservation. The government wanted them to stop this practice.

The reservation was very crowded. In 1872, there were 1,037 people. The Shoshone-Bannock struggled to find enough food. The government sent money to buy supplies. But there were food shortages in the winters of 1874–1875 and 1876–1877. This was because there was less game for hunters. Also, the government did not always provide enough food. Many Shoshone-Bannock left Fort Hall to find food on their own.

At the same time, the 1877 Nez Perce War made officials stricter. They demanded that Native Americans stay within reservation borders.

The Bannock War of 1878 happened for many reasons. The difficult conditions caused problems within the Shoshone-Bannock communities. The Bannock started to see the Shoshone as outsiders. They sometimes stole from them. Tensions also grew between Native Americans and European-Americans. In August 1877, a Native American named Pe-tope shot two teamsters. Agent William Danilson, the government agent at Fort Hall, wanted tribal leaders to punish Pe-tope. In response, a friend of Pe-tope, Nampe-yo-go, killed Alexander Rhodan, a beef contractor.

Agent Danilson asked the tribe to capture Nampe-yo-go. But the Shoshone-Bannock refused. Their tradition said that Nampe-yo-go's family should deal with his crime, not the whole tribe. That summer, many Shoshone-Bannock left the reservation. They left because of the lack of supplies, violence, and conflicts between tribes. This led to the Bannock War of 1878. The U.S. government ordered the Army to bring the people back to the reservation.

The Battles Begin

Camas Prairie Conflicts

In May 1878, Chief Buffalo Horn gathered 200 Bannock warriors. They left Fort Hall and went to the Big Camas Prairie. There were a few white settlers, 2500 cattle, and 80 horses in the area. On May 30, the Bannock tried to sell a buffalo skin to some cowboys. A fight broke out, and two cowboys were shot. They survived and went to a nearby camp. Soon after, white men attacked a Bannock camp. One settler was killed, and the Bannock lost their camp supplies.

News of the violence reached Boise City, Idaho. Governor Brayman told Brigadier General O. O. Howard, who was in charge of the military in the area. Brayman sent soldiers to the plains to show force. On June 2, the soldiers reached the Bannock camp. They forced the Bannock to retreat to the Lava Beds, which was a good place for defense. The Bannock moved west. They raided Glenn's Ferry and King Hill station, killing several settlers.

The soldiers followed the Bannock. They joined with more military and local volunteers. At this time, it was believed there were 300 Bannock warriors in the Lava Beds. Another 200 had raided other places. The Bannock were moving west to meet their Paiute allies.

Army vs. Bannock Warriors

On June 8, a group of 26 volunteer soldiers met Chief Buffalo Horn and his warriors. They fought at South Mountain. Two volunteers and several Bannock were killed, including Chief Buffalo Horn. The Bannock chose a new leader, Chief Egan. They headed to Juniper Mountain in Idaho and Steens Mountain in Oregon to meet the Paiute. Other states like California, Nevada, and Utah also sent their militias.

As the Bannock traveled west, they continued to raid camps. More settlers died. People in Idaho and nearby states worried the violence would spread. Soldiers followed Chief Egan's Bannock into Oregon. They fought on June 23 by Silver Creek. Three U.S. soldiers died, and three were wounded. The number of Bannock casualties is unknown.

On June 29, the Bannock fought with a volunteer militia. Soldiers arrived soon after and secured the area. The Bannock, estimated at 350 to 400 warriors, were moving toward Fox Valley. U.S. forces thought they wanted to join other Native American groups to the north.

On July 6, a volunteer group met hostile warriors near Willows Springs in Oregon.

General Howard fought the Bannock on July 7. Five U.S. soldiers were injured, and one died. The Bannock suffered an unknown number of casualties and moved southeast. The next fight was on July 12. Captain Miles met a large group of Umatilla warriors. The Umatilla felt threatened by the soldiers. They quickly surrendered and offered to fight with Miles against the Bannock. This conflict resulted in the deaths of five Bannock warriors, who then fled.

That night, Umatilla leaders went after the Bannock. They entered the Bannock camp pretending to talk. They then killed Chief Egan and several other warriors. On July 20, a group of soldiers met the Bannock in a canyon. The fight did not cause many deaths, but it forced the Bannock to retreat.

By July 27, General Howard changed his plan. Instead of fighting one large enemy, he pursued the smaller, scattered Bannock groups. Most of the final battles happened in August and September. The remaining Bannock returned to the Fort Hall Reservation. Some peaceful groups continued hunting on their own. A few more small fights happened, but no more deaths were recorded.

What Happened After the War

After the Bannock War of 1878, the American government limited the Bannock's movements. They could not easily leave or enter the Fort Hall Reservation. Their connections with other tribes were restricted. They also could not use local resources as freely. Weakened by the battles and lack of resources, the Bannock worked to rebuild their community on the reservation.

Other Bannock and Paiute prisoners were sent to the Malheur Reservation in Oregon. The Paiutes had been less involved in the war. But in November 1878, General Howard moved about 543 Bannock and Paiute prisoners from Malheur to the Yakama Indian Reservation in southeastern Washington Territory. They faced many hardships for years. In 1879, the Malheur Reservation was closed due to pressure from settlers.

Northern Paiutes from Idaho and Nevada were eventually released. In 1886, they were moved to an expanded Duck Valley Indian Reservation with their Western Shoshone relatives.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |