John Colter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Colter

|

|

|---|---|

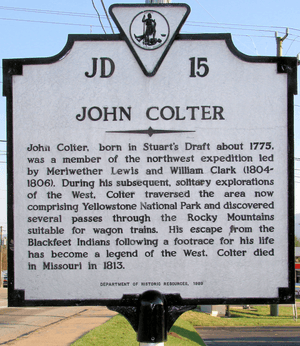

John Colter historical marker, located in Stuarts Draft, Virginia

|

|

| Born | c.1770–1775 Stuarts Draft, Colony of Virginia (present-day Stuarts Draft, Virginia)

|

| Died | May 7, 1812 or November 22, 1813 (age 36–43) Sullen Springs, St. Louis, Territory of Missouri (present-day St. Louis, Missouri)

|

| Resting place | Miller's Landing, Franklin County, Missouri (present-day New Haven, Franklin County, Missouri) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | John Coulter, John Coalter |

| Occupation | frontiersman, soldier, fur trapper |

| Employer | U.S. Government, self employed |

| Spouse(s) | Sallie Loucy |

| Children | 1 |

John Colter (born around 1770-1775, died 1812 or 1813) was a brave American explorer. He was part of the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition from 1804 to 1806. Colter is best known for his own amazing explorations. In the winter of 1807-1808, he became the first known person of European descent to explore the area that is now Yellowstone National Park. He also saw the Teton Mountain Range for the first time. Colter spent many months alone in the wild. People often call him the first true mountain man.

Contents

Early Life and Family

John Colter was born in Stuarts Draft, Virginia around 1774. His family believed this was his birth year. There are different spellings of his last name, like Coalter, Coulter, or Colter. Even William Clark used all three in his journals! We don't know if Colter could read or write much. However, two signatures show he could at least write his own name. Around 1780, his family moved west to what is now Maysville, Kentucky. As a young man, Colter might have worked as a ranger.

Joining the Lewis and Clark Expedition

John Colter joined the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1803. He met Meriwether Lewis in Pittsburgh. Lewis was impressed by Colter's outdoor skills. Colter was offered a job as a private and would earn five dollars a month.

The expedition set up its winter camp near St. Louis in December 1803. While Lewis and Clark were away, Colter and some others left camp without permission. When they returned, Lewis disciplined them. Later, Colter had a disagreement with a sergeant. He apologized and promised to do better, and was allowed to stay with the group.

Colter was one of the best hunters on the expedition. He often went out alone to find food for the group. He also helped the expedition find passes through the Rocky Mountains. Once, Clark chose Colter to deliver an important message to Lewis. Another time, he went back into the Bitterroot Mountains to find lost horses and supplies. He returned with them and even brought deer for the friendly Nez Perce tribes. Lewis noted that Colter was good at trading with different Native American tribes. This skill helped him later in life.

Colter was always healthy and rarely appeared on sick lists. He was one of the few hunters allowed to leave camp when others were sick. This shows how much Lewis and Clark trusted him. Colter also helped the group travel quickly down the Bitterroot Mountains. This allowed them to reach the Snake River and Columbia River, leading to the Pacific Ocean. While hunting, Colter met three Tushepawe Flatheads. He used peaceful signs to convince them to guide the expedition. This was a huge help in the difficult, unfamiliar mountains.

Once they reached the mouth of the Columbia River, Colter was chosen for a small group. They explored the Pacific Ocean coast. They also went north into what is now Washington state.

In 1806, the expedition returned to the Mandan villages in North Dakota. There, Colter met two fur trappers, Forest Hancock and Joseph Dickson. They were heading into the Missouri River area to trap beaver. Lewis and Clark allowed Colter to leave the expedition early. He joined the trappers to explore the region they had just seen. Colter had earned good pay for his time with the expedition.

Becoming a Mountain Man

Colter, Hancock, and Dickson went into the wilderness with beaver traps and supplies. Their exact route is not known. They might have avoided the unfriendly Blackfeet in the Lower Missouri area. Instead, they likely went to the Yellowstone Valley, where the Crows were friendlier. The dangerous Yellowstone River and lack of game might have caused their group to split up quickly.

The trio only stayed together for about two months. They reached a place where the Gallatin, Jefferson, and Madison Rivers meet. This spot is now called Three Forks, Montana. After a disagreement, Dixon left the group. Colter and Hancock spent the winter of 1806-07 together. A historian named J.K. Rollinson heard a story from Dave Fleming, the stepson of one of Colter's companions (likely Hancock). Fleming said his stepfather told him that Colter got restless during that winter. Colter climbed into the Sunlight Basin of modern-day Wyoming. This would make him the first known white man to enter this area.

In 1807, Colter started heading back to civilization. Near the Platte River, he met Manuel Lisa. Lisa was a founder of the Missouri Fur Trading Company. He was leading a group towards the Rocky Mountains. This group included some former Lewis and Clark members like George Drouillard and John Potts. Even though Colter was only a week away from St. Louis, he decided to return to the wilderness with Lisa's group.

At the meeting point of the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers, Colter helped build Fort Raymond. Lisa then sent Colter to find the Crow Indian tribe. He wanted Colter to see if they could trade with them.

Exploring Yellowstone and Grand Teton

Colter left Fort Raymond in October 1807. He traveled over 500 miles to trade with the Crow nation. During that winter, he explored the region that later became Yellowstone National Park and Grand Teton National Park. Colter reportedly saw at least one geyser basin. It's believed he was near present-day Cody, Wyoming, which had some geothermal activity back then.

Colter likely traveled along parts of Jackson Lake. He crossed the Continental Divide near Togwotee Pass or Union Pass. Then he explored Jackson Hole, below the Teton Range. He later crossed Teton Pass into Pierre's Hole (now Teton Basin in Idaho). After heading north and east, he probably saw Yellowstone Lake. Here, he also saw geysers and other hot features. Colter returned to Fort Raymond in March or April 1808. He had traveled hundreds of miles, often alone, in the middle of winter. Temperatures in January in that region can drop to -30°F!

When Colter returned to Fort Raymond, few believed his stories. They laughed at his reports of geysers, bubbling mudpots, and steaming pools. They jokingly called the region "Colter's Hell". The area Colter described is now thought to be west of Cody, Wyoming. While there is thermal activity there, other reports from that time also mention similar features. The exact location of "Colter's Hell" is still debated. It might have referred to several areas with hot springs. It's commonly believed to be the area of the Stinking Water (now Shoshone River) near Cody. The river got its original name from the sulfur in the area. Colter's detailed exploration of this region was the first by a white man in what is now Wyoming.

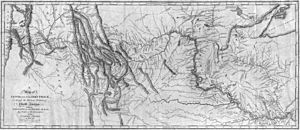

Colter's Route on Maps

We don't know if Colter drew his own map or just told William Clark the details. Colter's Route was included on Clark's map, called "A Map of Lewis and Clark's Track Across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean." This map was published in 1814. Clark's first sketches, drawn in 1807, didn't include Colter's route because Colter was still exploring. A later version of these maps from 1810 included details from Colter. Some parts of the 1814 map had errors, like the Big Horn Mountains being drawn too large. Historians are still unsure why these errors exist.

Colter's Famous Run

The next year, Colter teamed up with John Potts. Potts was also a former member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. They were again near Three Forks, Montana. In 1808, Colter and Potts left Fort Raymond to make trade deals with local tribes. While leading 800 Flathead and Crow Indians back to the fort, Colter's group was attacked by over 1,500 Blackfeet. The Flatheads and Crows fought back and made the Blackfeet retreat. Colter was wounded in the leg, but it wasn't serious. He recovered quickly.

In 1809, Colter and Potts had another fight with the Blackfeet. This time, Potts was killed, and Colter was captured. They were going up the Jefferson River in a canoe when hundreds of Blackfeet demanded they come ashore. Colter went ashore and was disarmed and stripped naked. Potts refused to come ashore and was shot. Potts then shot one of the Blackfeet warriors and was immediately killed by arrows.

After a discussion, Colter was told to run. A group of Blackfeet chased him. He ran 5 miles to the Madison River. He hid inside a beaver lodge and escaped. At night, he came out and walked for eleven days. He finally reached a trading fort on the Little Big Horn. This amazing escape became known as "Colter's Run."

In 1810, Colter helped build another fort at Three Forks, Montana. When he returned from collecting furs, he found that two of his partners had been killed by the Blackfeet. This event made Colter decide to leave the wilderness for good. He returned to St. Louis before the end of 1810. He had been away from civilization for almost six years.

Later Life and Death

After returning to St. Louis, Colter married a woman named Sallie. He bought a farm near Miller's Landing, Missouri. Around 1810, he met with William Clark and gave him detailed reports of his explorations. Clark used this information to create a map. Even with some errors, it was the most complete map of the region for the next 75 years. During the War of 1812, Colter joined and fought with Nathan Boone's Rangers.

It's not clear exactly when or how Colter died. One report says he got sick with jaundice and died on May 7, 1812. He was buried near Miller's Landing. Other sources say he died on November 22, 1813.

Colter's Legacy

Colter's story greatly shaped how people saw the American West. His famous "Colter's Run" has been retold many times, including by writer Washington Irving. The idea of a lonely, wild mountain man might have come from how Nicholas Biddle described Colter. Biddle wrote that Colter was easily drawn to trapping and scared of returning to normal life. Since Colter didn't leave any writings (besides his signature), we can't know his true thoughts.

It's often thought that the Lewis and Clark Expedition made things worse between white explorers and the Blackfeet Indians. However, Manuel Lisa's group first had peaceful interactions with the Blackfeet. It was after Colter and Potts fought alongside the Flatheads and Crows against the Blackfeet that relations seemed to get worse. Many frontiersmen believed Colter had caused problems with the Blackfeet, especially after his famous run.

Many places in northwestern Wyoming are named after him. These include Colter Bay on Jackson Lake in Grand Teton National Park. There's also Colter Peak in the Absaroka Mountains in Yellowstone National Park. A plaque honoring Colter is near his birthplace in Stuarts Draft, Virginia. Another historical marker in Maysville, Kentucky remembers him as one of the "nine young men from Kentucky" on the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Colter Stone and Other Artifacts

Between 1931 and 1933, a farmer named William Beard and his son found a rock. It was carved into the shape of a man's head. They found it while clearing a field in Tetonia, Idaho, west of the Teton Range. This rock is made of rhyolite lava. It is 13 inches long, 8 inches wide, and 4 inches thick. The words "John Colter" are carved on the right side of the face, and "1808" is on the left. This rock is called the "Colter Stone."

A man named A.C. Lyon bought the stone in 1933. He gave it to Grand Teton National Park in 1934. A geologist and park naturalist, Fritiof Fryxell, studied the stone. He thought the carvings looked like they were made in 1808. Fryxell also believed the Beards didn't know about John Colter. However, the stone has not been fully proven to be carved by Colter himself. If it is real, it would mean Colter was in that area in 1808. It would also confirm that he crossed the Teton Range into Idaho, as he described to William Clark.

Another possible artifact linked to Colter was found in Yellowstone National Park in the 1880s. It was a log with the carved initials "J C" under a large X. It was found near Coulter Creek, a stream with a similar name but no relation to Colter. Experts thought the carving was about eighty years old. Sadly, this artifact was lost around 1890 while being moved to the park museum.

Colter in Popular Culture

- The first movie about John Colter's life was a silent film from 1912, called John Colter's Escape.

- The 1965 movie The Naked Prey was largely based on Colter's story of being chased by Blackfeet Indians.

- Other movies like Run of the Arrow (1957) and The Mountain Men (1980) have scenes similar to Colter's Run.

- A.B. Guthrie's 1947 story "Mountain Medicine" is a fictional version of Colter's Run.

- The TV series Into The Wild Frontier (2022) has an episode about John Colter. It's Season 1, Episode 1: "John Colter: King of the Mountain Men."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John Colter para niños

In Spanish: John Colter para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |