Jefferson River facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jefferson River |

|

|---|---|

Where the Beaverhead and Big Hole Rivers meet to form the Jefferson River near Twin Bridges, Montana

|

|

Montana rivers. The Jefferson–Beaverhead–Red Rock is in the southwest corner.

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Twin Bridges, Montana 45°34′05″N 112°20′21″W / 45.56806°N 112.33917°W |

| River mouth | Missouri River Three Forks, Montana 45°55′39″N 111°30′29″W / 45.92750°N 111.50806°W |

| Length | 83 mi (134 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 9,532 sq mi (24,690 km2) |

| Tributaries | |

The Jefferson River is a river in Montana, United States. It flows for about 83 miles (134 km). This river is a tributary, which means it's a smaller river that flows into a larger one. The Jefferson River flows into the Missouri River.

Together with the Madison River, the Jefferson River forms the official start of the Missouri River. This happens at Missouri Headwaters State Park near Three Forks. A little further downstream, the Gallatin River also joins them.

The Jefferson River flows through many different types of land. It goes from wide, open valleys to narrow canyons. This area has some of the oldest and newest rocks in North America. You can find many different kinds of rocks here, like igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks.

Native American tribes lived in this area at different times. No single tribe owned the Jefferson River when the Lewis and Clark Expedition first explored it in 1805. Today, the Jefferson River still has much of its natural beauty and many kinds of wildlife. However, it faces challenges from water use and new buildings. The Jefferson is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. This trail is managed by the National Park Service.

Contents

Where Does the Jefferson River Flow?

The Jefferson River starts in the Rocky Mountains of southwestern Montana. Three smaller rivers come together to form its beginning. The longest of these starts at Brower's Spring. This spot is 9,030 feet (2,750 m) high and is marked by a pile of rocks.

The water from Brower's Spring first flows as Hell Roaring Creek. It then joins Rock Creek and becomes the Red Rock River. This river flows through Lima Reservoir and then into Clark Canyon Reservoir near Dillon.

Below this dam, the river is called the Beaverhead River. The Ruby River joins it near Twin Bridges. Then, the Beaverhead River meets the Big Hole River. This meeting point is about two miles downstream from Twin Bridges, and it's where the Jefferson River officially begins.

The River's Journey to the Missouri

The Jefferson River flows north through the Jefferson Valley, past Whitehall. Then it turns east. The Boulder River joins it here. The Jefferson then flows through a narrow canyon near Lewis and Clark Caverns State Park.

After the canyon, the river opens up into a wide valley again near Willow Creek. Finally, the Jefferson River meets the Madison River at Missouri Headwaters State Park near Three Forks. This is where the mighty Missouri River officially starts. A short distance later, the Gallatin River also joins the Missouri.

The water from the Jefferson River then travels a very long way. It flows into the Missouri River, then into the Mississippi River, and finally reaches the Gulf of Mexico. These rivers together form the fourth longest river system on Earth.

The Story of the Rocks: Jefferson River Geology

The land around the Jefferson River has some of the oldest rocks in North America. Some of these rocks are 2.7 billion years old! These ancient rocks are metamorphic, meaning they changed form due to extreme heat and pressure deep underground. You can find them in the Tobacco Root and Ruby mountain ranges.

These old rocks often include layers of feldspars, gneiss, quartz, and sometimes marble. About a billion years ago, a large crack in the Earth's crust, called the Willow Creek Fault, formed north of the Jefferson River canyon. Seawater filled this crack, stretching far to the north.

Later, the sea went away, and erosion wore down the land. Then, about 530 million years ago, during the Cambrian Period, a new sea covered the area. This sea left behind layers of sedimentary rocks. These include limestone, dolomite, shale, and sandstone.

What are Sedimentary Rocks?

- Limestone is usually made from the shells and skeletons of tiny sea animals that have been pressed and glued together.

- Dolomite is similar to limestone but has more magnesium.

- Shale forms from fine mud, silts, and clays that have been compacted.

- Sandstone is made of grains of quartz and feldspar.

About 340 million years ago, much of western North America was covered by a warm, shallow sea. This was like the Gulf Coast of Florida today. You can find small marine fossils in the Madison Group limestone in the Jefferson River canyon.

Over time, the land slowly rose above sea level again. Rainwater seeped into cracks in the limestone, dissolving the rock. This created amazing caves, like those at Lewis and Clark Caverns State Park.

How Mountains Formed Here

Local mountains, like the Tobacco Roots, were formed by something called the Boulder Batholith. A batholith is a very large mass of igneous rock. Igneous rocks form when hot, melted rock (magma) cools and hardens underground.

The Boulder Batholith formed about 73 to 78 million years ago. This happened when magma pushed up from deep inside the Earth. This magma came from subduction, where one part of the Earth's crust slides under another. Over time, the deep-seated granite rock was pushed to the surface. Erosion then exposed these rocks and the valuable minerals they contained, like gold and silver.

The ancient metamorphic rocks and newer sedimentary layers that were above the batholiths wore away as the magma pushed up. This is why the granite batholiths are usually found in the center of mountain ranges. The older metamorphic rocks are lower down, and the limestone layers are often in the foothills near the river.

The Rocky Mountains began to stretch and pull apart again about 5 to 10 million years ago. This caused blocks of earth to drop down, forming valleys. The Jefferson River then carved its way through the rock, creating the Jefferson River canyon.

Native American History Along the River

Archaeologists believe the first people came to America from Asia. They crossed a land bridge between 12,000 and 30,000 years ago. These early people, called Paleo-Indians or Clovis people, hunted large animals like mammoths and bison. They used special spear points called Clovis points. Clovis points from 12,000 to 13,000 years ago have been found near the Missouri River.

Upstream from the Jefferson, at Barton Gulch, archaeologists found old cooking pits and ovens used by Paleo-Indians about 9,400 years ago.

Between 6,000 and 7,000 years ago, the climate became much drier. It's thought that fewer animals lived in the Northern Rockies, and many native peoples likely moved away. Montana was probably only lived in off and on after that for a long time.

Tribes and Their Journeys

In the 1500s, the Kootenai people came into Montana from the north. The Salish and Pend d'Oreille tribes also moved in from the north and northwest. They traveled south to the Jefferson River area.

Major changes in where people lived began in the early 1600s. New tribes came into Montana. The Shoshone people, who had horses from Spanish settlers, moved into Montana from the Great Basin. They hunted buffalo and became a very important tribe in the area.

However, as European settlers moved west, it pushed Native American tribes further west. This had a "domino effect" all the way to Montana. The Crow tribe came into Montana from the east in the 1600s. Then, the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, and Assiniboine tribes arrived in the 1700s.

With guns and horses, the Blackfeet became the most powerful tribe on the plains in the 1700s. The Shoshone were mostly pushed back into Idaho, but they still came into Montana to hunt. By 1800, the Missouri headwaters and southwest Montana were a busy place. Many tribes visited, including the Lemhi Shoshone, Bannock, Nez Perce, Flathead, Crow, Sioux, and Piegan Blackfeet.

Sacagawea, a young woman from the Lemhi Shoshone tribe, was captured by the Hidatsa people on the lower Jefferson River in 1800. She was about twelve years old then. Later, she married Toussaint Charbonneau. Both of them joined the Lewis and Clark Expedition when Lewis and Clark spent the winter with the Hidatsa in North Dakota.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition on the Jefferson River

At the start of the 1800s, not much was known about the American West. The Missouri River flowed southeast from a mystery source. The Columbia River started at a similar latitude and flowed west to the Pacific Ocean. What was in between these two rivers was a big question.

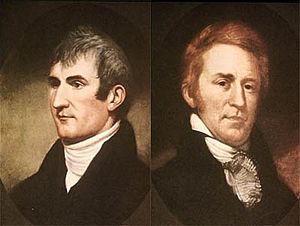

The United States bought the land that included the Missouri River in 1803. This was called the Louisiana Purchase. President Thomas Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the Missouri River. They hoped to find a water route to the Pacific Ocean, with an easy portage (carrying boats over land) between the two river systems.

The expedition left Saint Louis, Missouri, in the spring of 1804. They traveled up the Missouri River that summer. They spent the winter with the Hidatsa Indians in North Dakota. There, they met Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea. Lewis and Clark hired Charbonneau because Sacagawea's people lived near the Missouri headwaters.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition reached the Missouri Headwaters on July 27, 1805.

Naming the Rivers

There are three streams that form the headwaters of the Missouri River. The eastern one is the smallest. The middle and western ones are about the same size. Lewis and Clark decided that none of them should keep the name "Missouri."

Instead, they named the western fork the Jefferson, after President Thomas Jefferson. They named the middle fork the Madison, after the Secretary of State. And they named the eastern fork the Gallatin, after the Secretary of the Treasury. Meriwether Lewis wrote about this in his journal on July 28, 1805:

- "Both Capt. C. and myself agreed that it would be wrong to call any of these streams the Missouri. So we decided to name them after the President of the United States and the Secretaries of the Treasury and State..."

The expedition rested for a couple of days. Then, they started to go up the Jefferson River. They used ropes to pull their dugout canoes against the current. Along the way, they hunted deer, elk, and bighorn sheep. They also saw grizzly bears.

On August 2, 1805, Lewis described the upper Jefferson River:

The valley where we traveled today, and where the river winds, is a beautiful flat plain. There are few trees, mostly along the river's edge. The land is quite fertile, with dark soil, and covered with grass. The plain rises gently on both sides of the river to the base of two mountain ranges. These mountains run next to the river and mark the valley's width. The tops of these mountains still had some snow, while we in the valley were almost suffocated by the intense heat of the midday sun. The nights are so cold that two blankets are barely enough to stay warm.

When they reached another major meeting of rivers, Lewis and Clark named the western fork the Wisdom River. They named the eastern fork the Philanthropy River. They kept the middle fork as the Jefferson River. However, these names were not kept. Today, these rivers are known as the Big Hole, the Ruby, and the Beaverhead.

The Jefferson River is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. This trail was created by Congress in 1978 and is managed by the National Park Service.

Fun on the Jefferson River: Recreation

The Jefferson River is a great place for outdoor activities. It's known as "Class I water" for fun activities. This means it's suitable for most people, from where it starts to where it meets the Missouri River.

The river is good for floating and for people who are just starting to paddle canoes or kayaks. But be careful during high water in the spring. Some dangers can include fallen trees, called "sweeps," and dams that send water into irrigation ditches. In mid-summer, the water level often drops. This means you might have to drag your boat over shallow, rocky areas.

The Jefferson River has three main parts:

Upper Jefferson River: A Winding Wonderland

The upper Jefferson is a very winding river with many small channels. It flows through a floodplain, which is a flat area next to the river that can flood. This area has rich farmlands, many cottonwood trees, green meadows, and lots of wildlife.

The river naturally moves across the Jefferson Valley. This creates different habitats like oxbows (U-shaped bends) and swamps of various depths and ages. When the river shifts and floods, it helps new cottonwood tree seeds grow. Groups of cottonwood trees often grow after a single flood, so they tend to be the same age. The upper Jefferson stretches about 44 miles downstream to the community of Cardwell.

Middle Jefferson River: The Narrow Canyon

The middle Jefferson enters a narrow canyon a short distance downstream from Cardwell. The canyon walls hold the river in for most of the next 15 miles. Because the river can't flood or wander much here, this section has fewer trees, swamps, meadows, and less wildlife than the upper Jefferson.

Lower Jefferson River: Back to Wide Open Spaces

The lower Jefferson opens up again into a winding, braided river. It flows about 24 miles downstream from Sappington Bridge to where it meets the Madison River. In this section, the land along the river (called the riparian zone) again supports many swamps, meadows, cottonwood groves, and productive farmlands.

Challenges for the Jefferson River

The Jefferson River's water is used a lot for irrigating farms and ranches. Dams upstream on the Ruby and Beaverhead rivers store extra water from spring snowmelt. This water is then released in the summer to help with irrigation.

However, in dry years, parts of the river can become very shallow and warm. This can harm fish populations. The unusually warm water, along with extra nutrients from farm runoff, can cause algae to grow quickly in mid-summer. This is not good for people who like to fish or float on the river.

For example, on August 5, 2016, the Jefferson River's flow was very low. Even though its three main rivers were adding a lot of water, farmers used over 98% of it for irrigation. This left less than 2% of the water in the river itself. Montana does not have laws to prevent the river from losing almost all its water in the future.

While much of the Jefferson River is still beautiful and natural, it is threatened by new housing developments. These developments slowly break up the natural homes for wildlife and block scenic views along the river.

Also, some people try to stop the riverbanks from eroding by using rocks, concrete, and other materials. This stops the river from flooding naturally, which is important for creating new cottonwood groves and wildlife habitats. These hardened sections of the river can also push floodwaters downstream, causing more problems for other landowners.

Who Helps the Jefferson River?

Many groups work to protect and improve the Jefferson River:

- Jefferson River Watershed Council — This group works with the community to protect the natural resources, quality of life, and economy of the Jefferson River area.

- Jefferson River Canoe Trail — This group is part of the Lewis & Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Their goal is to protect the land and history of the Jefferson River and nearby parts of the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail.

- Trout Unlimited — This organization works to protect and restore coldwater fish habitats and their rivers in North America.

- Western Watersheds Project — This group aims to protect and restore western rivers and wildlife. They do this through education, public policy, and legal actions.

- Montana River Action — This group believes that Montana's clean rivers belong to the people. Their mission is to protect and restore rivers, streams, and other water bodies in Montana.

See also

In Spanish: Río Jefferson para niños

In Spanish: Río Jefferson para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |