Minidoka National Historic Site facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Minidoka National Historic Site |

|

|---|---|

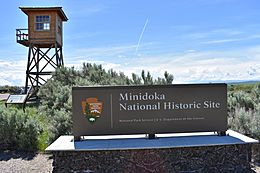

Entrance and guard tower in 2019

|

|

| Location | Hunt, Idaho, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Eden |

| Area | 210 acres (85 ha) |

| Authorized | January 17, 2001 |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Minidoka National Historic Site |

|

Minidoka National Historic Site

|

|

The Minidoka National Historic Site is a special place in the western United States. It remembers the more than 13,000 Japanese Americans who were forced to live at the Minidoka War Relocation Center during World War II. Many of these people were American citizens.

This site is located in a remote desert area in Hunt, Idaho. It is about 20 miles (32 km) northeast of Twin Falls. The National Park Service takes care of the site. It was first created as a National Monument in 2001. The area is nearly 4,000 feet (1,219 m) above sea level.

Contents

Minidoka War Relocation Center: A Wartime Camp

The Minidoka War Relocation Center was open from 1942 to 1945. It was one of ten camps where people of Japanese heritage were held during World War II. These people included both American citizens and immigrants.

This happened because of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066. This order forced all people of Japanese ancestry to leave the West Coast of the United States. At its busiest, Minidoka held 9,397 Japanese Americans. Most of them came from Oregon, Washington, and Alaska.

Building the Camp and Daily Life

The Minidoka camp was built in 1942. By the end of that year, it held 10,000 people. Many of the people held at Minidoka worked on farms. They also helped with an irrigation project and built the Anderson Ranch Dam.

A law from 1902 had rules about who could work on these projects. These rules were changed in 1943 so that Japanese Americans could work. The number of people at Minidoka went down to 8,500 by late 1943. By the end of 1944, it was 6,950.

The camp officially closed on October 28, 1945. After the war, the camp buildings were used to house soldiers returning home.

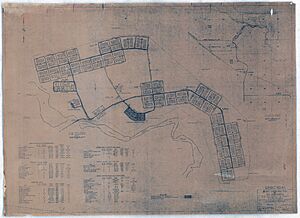

The Minidoka War Relocation Center had 44 housing blocks. Each block had 12 barracks, which were like small apartments. They also had laundry rooms, bathrooms, and a dining hall. Each block had a recreation hall for worship and learning.

Minidoka had a high school, a junior high school, and two elementary schools. The camp also had shops like dry cleaners, general stores, and barber shops. There were even radio and watch repair stores, plus two fire stations.

Japanese Americans in the Military

In 1942, the U.S. Army formed the 100th Infantry Battalion. This group had 1,432 men of Japanese descent from the Hawaii National Guard. They were sent for training.

Because they trained so well, President Roosevelt created the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) in 1943. About 10,000 men from Hawaii signed up, and 2,686 were chosen. Another 1,500 came from the mainland.

The people at Minidoka made an Honor Roll to celebrate the Japanese Americans serving in the military. About 844 men from this camp volunteered or were drafted. The original Honor Roll was lost, but a new one was made in 2011.

Understanding the Words We Use

Since World War II ended, people have talked about the best words to describe Minidoka and other camps. These camps held Americans of Japanese ancestry and their immigrant parents.

You might hear Minidoka called a "War Relocation Center," "relocation camp," "internment camp," or even a "concentration camp." People still discuss which term is the most accurate and fair.

Minidoka as a National Historic Site

The camp site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. In 2001, President Bill Clinton made it a national monument. This means it is a special place protected by the government.

Minidoka is one of the newer places in the National Park System. It has visitor facilities and services. A new visitor center was planned to open in 2020. Visitors can see the remains of the guard station and a rock garden.

You can also learn more at the Jerome County Museum in nearby Jerome. There is also a restored barracks building at the Idaho Farm and Ranch Museum. Signs at the site tell some of the camp's history.

In 2006, President George W. Bush signed a law that gave $38 million to help restore Minidoka and nine other former Japanese internment camps.

In 2008, President Bush signed another law. This law changed Minidoka from a National Monument to a National Historic Site. It also added the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial in Washington to the site.

There is a plan for a wind farm nearby called the Lava Ridge Wind Project. The plan was changed to make sure the wind turbines are at least 9 miles (14 km) away from Minidoka. This helps protect the historic site.

People Connected to Minidoka

Many people who were held at Minidoka went on to do important things. Here are a few:

- Paul Chihara (born 1938), a composer.

- May Mayko Ebihara (1934–2005), an anthropologist.

- Fumiko Hayashida (1911–2014), an activist.

- Shiro Kashino (1922–1997), a decorated soldier in World War II.

- Taky Kimura (1924–2021), a martial arts instructor.

- Fujitaro Kubota (1879–1973), a gardener and giver to charity.

- Aki Kurose (1925–1998), a teacher and civil rights activist.

- William K. Nakamura (1922–1944), a soldier who received the Medal of Honor.

- George Nakashima (1905–1990), a woodworker and furniture maker.

- Roger Shimomura (born 1939), an artist and professor.

- Monica Sone (1919–2011), a novelist.

- Minoru Yasui (1916–1986), a lawyer who challenged unfair curfew laws during the war.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |