Shoshoni language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Shoshoni |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sosoni' ta̲i̲kwappe, Neme ta̲i̲kwappeh | ||||

| Native to | United States | |||

| Region | Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Idaho | |||

| Ethnicity | Shoshone people | |||

| Native speakers | 1,000 (2007)e18 1,000 additional non-fluent speakers (2007) |

|||

| Language family |

Uto-Aztecan

|

|||

| Early forms: |

Proto-Numic

|

|||

| Dialects |

Western Shoshoni

Northern Shoshoni

Eastern Shoshoni

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin | |||

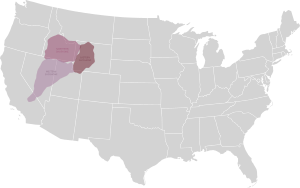

Map of the Shoshoni (and Timbisha) languages prior to European contact

|

||||

|

||||

Shoshoni is a language spoken by the Shoshone people in the Western United States. You might also see it called Shoshoni-Gosiute or Shoshone. It belongs to the Numic group, which is part of the larger Uto-Aztecan language family.

Most Shoshoni speakers live in the Great Basin area. This includes parts of Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and Idaho. The language has a small set of basic sounds (consonants and vowels). It uses many endings (suffixes) to change the meaning of words. This helps show things like if a word is singular or plural, or when an action happened.

The Shoshoni people have their own names for their language. Newe ta̲i̲kwappe means "the people's language." Sosoni' ta̲i̲kwappe means "the Shoshoni language." Sadly, Shoshoni is considered a threatened language. But people are working hard to keep it alive!

Contents

Understanding the Shoshoni Language

Shoshoni is part of the big Uto-Aztecan language family. This family has almost 60 living languages. They are spoken from the Western United States all the way down to El Salvador. Shoshoni is the northernmost language in this family.

What is Numic?

Shoshoni is also part of the Numic group. The word Numic comes from a word that means "person" in all Numic languages. For example, in Shoshoni, "person" is neme or newe.

Shoshoni's Closest Relatives

Shoshoni's closest language relatives are Timbisha and Comanche. These are also Central Numic languages.

Timbisha is spoken in southeastern California. It is spoken by the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe. Even though it's close, Timbisha is seen as a different language from Shoshoni.

The Comanche people separated from the Shoshone around the year 1700. Over time, the sounds in their languages changed. This means that Comanche and Shoshoni speakers now have trouble understanding each other.

Different Ways to Speak Shoshoni

Shoshoni has several main dialects, which are like different versions of the language.

- Western Shoshoni is spoken in Nevada.

- Gosiute is spoken in western Utah.

- Northern Shoshoni is found in southern Idaho and northern Utah.

- Eastern Shoshoni is spoken in Wyoming.

The biggest differences between these dialects are in how words sound.

The Future of Shoshoni

The number of people who speak Shoshoni has been going down. In the early 2000s, only a few hundred to a few thousand people spoke it fluently. About 1,000 more people knew some of the language but were not fluent.

Efforts to Keep the Language Alive

Many communities are working to save the Shoshoni language.

- The Duck Valley and Gosiute communities have programs. They teach the language to their children.

- Ethnologue calls Shoshoni "threatened." This is because many fluent speakers are 50 years old or older.

- UNESCO says Shoshoni is "severely endangered" in Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming.

- Even so, the language is still taught to children in a few places.

- Tribes really want to bring the language back. Efforts are happening, but they are not always connected.

- More people are learning to read and write Shoshoni. Dictionaries have been made. Parts of the Bible were translated in 1986.

Learning Shoshoni Today

- Since 2012, Idaho State University has offered Shoshoni classes. This is part of a 20-year project to save the language. You can even find free Shoshoni audio online to help with learning.

- The Shoshone-Bannock Tribe teaches Shoshoni to kids and adults. This is part of their Language and Culture Preservation Program.

- On the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, elders are saving recordings of the language.

- Shoshoni is taught using special methods to help people learn it faster.

Fun Ways to Learn Shoshoni

- A summer program called SYLAP (Shoshone/Goshute Youth Language Apprenticeship Program) started in 2009. It's at the University of Utah. Young Shoshoni people help turn old recordings into digital files. This makes them available for tribal members.

- In 2013, this program even released the first Shoshone language video game!

- In 2012, Blackfoot High School in Idaho started offering Shoshoni classes.

- The Chief Tahgee Elementary Academy opened in 2013. It's a school at Fort Hall that teaches both English and Shoshoni.

How Shoshoni Sounds

Shoshoni has a typical set of sounds for Numic languages.

Vowels

Shoshoni has five main vowel sounds. These vowels can be short or long. There is also a special sound, `ai`, which acts like a vowel. It can sometimes sound like `e`.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| High | short | i | ɨ | u |

| long | iː | ɨː | uː | |

| Mid | short | ai | o | |

| long | aiː | oː | ||

| Low | short | a | ||

| long | aː | |||

Consonants

Shoshoni also has a typical set of consonant sounds for Numic languages.

| Bilabial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Stop | p | t | k | kʷ | ʔ | |

| Affricate | t͡s | |||||

| Fricative | s | h | ||||

| Semivowel | j | w | ||||

Word Stress

In Shoshoni, stress (which part of a word you say louder) is usually on the first part of a word. But if the second part of the word is long, the stress moves there. For example, in natsattamahkantɨn ("tied up"), the stress is on the first part. But in kottoohkwa ("made a fire"), the stress is on the second part because it has a long vowel sound.

How Shoshoni Words Are Built

Shoshoni is an agglutinative language. This means words, especially verbs, can be very long. They are made by sticking many small parts (called morphemes) together. Shoshoni mostly uses suffixes, which are endings added to words.

Nouns: People, Places, Things

Special Noun Endings

Many Shoshoni nouns have a special ending called an "absolutive suffix." This ending usually disappears when the noun is part of a longer word or followed by another ending. For example, sɨhɨpin means "willow." But if you say "to gather willows," it becomes sɨhɨykwi, and the -pin ending is gone.

Singular, Dual, and Plural

Shoshoni nouns change their form to show if there is one, two, or many of something. This is called number.

- Singular (one) has no special ending.

- Dual (two) uses the ending -nɨwɨh for people.

- Plural (many) uses the ending -nɨɨn for people.

Nouns also change to show their case. Case tells you if a noun is the subject (doing the action), the object (receiving the action), or showing possession (owning something).

Verbs: Actions and States

Verb Number

Shoshoni verbs can also show number. This means the verb changes if one person, two people, or many people are doing the action.

- Sometimes, the first part of the verb is repeated. For example, kimma ("come") for one person becomes kikimma for two people.

- Sometimes, the verb changes completely. For example, yaa ("carry") for one person becomes hima for two or more people.

Action Prefixes

Shoshoni uses prefixes (beginnings added to words) to show how an action is done. These are called "instrumental prefixes." They tell you what part of the body or what tool was used.

Here are some examples:

- kɨ"- means "with the teeth or mouth."

- to"- means "with the hand or fist." So, tsima ("scrape") becomes tottsima ("wipe").

- ta"- means "with the feet."

- wɨ"- means "with a long tool or body part." It can also be a general tool prefix.

How Shoshoni Sentences Are Made

Word Order

The usual word order in Shoshoni sentences is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV). This means the person or thing doing the action comes first, then the thing receiving the action, and finally the action itself.

For example:

- nɨ hunanna puinnu means "I saw a badger." (Literally: "I badger saw.")

- nɨwɨ sakkuhtɨn paittsɨkkinna means "the person was making a fuss there." (Literally: "person there was hollering.")

Sometimes, the subject (the person or thing doing the action) is not even in the sentence. This happens if it's clear from the situation who is doing the action. For example, if you're telling a story about someone killing another, you might just say u paikkahkwa ("him killed"). The listener knows who "he" is from the story.

The meaning of a Shoshoni sentence does not always depend on the word order. So, sometimes the subject can come after the object.

Combining Sentences

Relative Clauses

Shoshoni uses "relative clauses" to add more information about a noun. For example, "the woman who was crying arrived."

If the subject of the smaller clause (like "who was crying") is the same as the main subject ("the woman"), special endings are added to the verb.

If the subjects are different, the subject of the smaller clause changes its case. For example, in "this fish that we are eating tastes rotten," "we" is the subject of "eating." It becomes "our" (possessive case).

Writing Shoshoni

There isn't one single way to write Shoshoni that everyone agrees on. Different writing systems exist. There are also different ideas among Shoshoni speakers about whether the language should be written down at all.

Some people believe Shoshoni should stay an oral language. They think this protects it from outsiders. Others argue that writing it down will help save it and make it useful today.

Main Writing Systems

The two main writing systems for Shoshoni are:

- The Crum-Miller system: This was created in the 1960s by Beverly Crum (a Shoshone elder) and Wick Miller (a linguist). It focuses on showing the basic sounds of the language.

- The Idaho State University system (or Gould system): This was developed by Drusilla Gould (a Shoshone elder) and Christopher Loether (a linguist). It is used more in southern Idaho. This system tries to show how words are actually pronounced.

You can find Shoshoni dictionaries online to help with everyday use.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma shoshoni para niños

In Spanish: Idioma shoshoni para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |