Timbisha facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 124 (2010 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

The Timbisha people, whose name means "rock paint" in their language, are a Native American tribe. They are officially recognized by the U.S. government as the Death Valley Timbisha Shoshone Band of California. They are also known as the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe. You can find them in south central California, close to the Nevada border. In 2010, about 124 people lived in their village. Older members of the tribe still speak their traditional language, which is also called Timbisha.

Contents

History of the Timbisha Shoshone People

The Timbisha people have lived in the Death Valley area of North America for more than a thousand years. They were first known as Panamints, which was also the name of their language. This group was traditionally very small. Experts believe fewer than 200 people ever spoke the Panamint Shoshone language.

People from Europe and America first met the Timbisha Shoshone during the California Gold Rush in 1849. However, these newcomers quickly moved on to find gold. This left the Shoshone homeland with its current name, Death Valley.

More regular contact happened from the 1860s to the 1880s. During this time, many ranchers, miners, and settlers moved to Death Valley. They claimed the few water sources and good land. New settlers used laws to take control of the Valley's limited water and land. This forced the Shoshone people onto less desirable land. The settlers' animals also ate plants that the tribe needed for food. Some of their original lands now include the Furnace Creek Inn and golf course.

The U.S. government did not officially recognize the Timbisha Shoshone as a tribe for a long time. Like many small Native American groups in California, their rights were not protected. Later, the Bureau of Indian Affairs did help a Timbisha man named Hungry Bill claim 160 acres of land near Death Valley in 1908. They also helped Robert Thompson get land at Warm Springs in Death Valley. In 1928, federal agents created a small settlement called "Indian Ranch" east of Death Valley for Panamint Bill and his family. Even without official recognition, some Timbisha Shoshone attended federal Indian boarding schools in the early 1900s.

Establishing Death Valley National Monument

In 1933, President Herbert Hoover created Death Valley National Monument. This action meant the tribe's homeland was now inside the park's boundaries. Even though the Timbisha had lived there for a long time, the park's creation did not give them their own homeland.

After attempts to move the tribe to other reservations failed, the National Park Service made an agreement with tribal leaders. In 1938, the Civilian Conservation Corps built an Indian village for tribal members. This village was near the park's main office at Furnace Creek. From then on, tribal members lived within the monument. However, park officials often questioned their right to be there.

The Timbisha also lived in the Great Basin Saline Valley and northern Mojave Desert areas of southeastern California. In some border areas, it was common for settlements to include people speaking different but related languages.

Challenges and Efforts for Recognition

During the 1950s, National Park Service officials tried to remove the Shoshone people from Indian Village. The park had already stopped the Shoshone from continuing their traditional ways of life. This included gathering firewood and plants, hunting, and holding sacred ceremonies within the monument.

The adobe houses built in the 1930s were falling apart by the mid-1900s. An electric line was very close to the village, but the Park Service did not pay to extend it to the homes. The houses had no electricity, air conditioning, indoor plumbing, or running water.

Using these poor conditions as a reason, the Park Service started a plan in 1957 to remove the Timbisha Shoshone from Indian Village. They began charging rent and evicting people who could not pay. They also limited who could live there to only current residents and their close relatives. Park officials hoped these rules would eventually cause the village to disappear. Many Shoshone men had already moved away for jobs in nearby Beatty, Nevada, or to cities in California.

The 1950s was a time when the U.S. government tried to end its relationship with Native American tribes. In 1958, Congress closed "Indian Ranch," the settlement created earlier for Panamint Bill.

At this time, Pauline Esteves, a tribal member, began fighting the National Park Service's plan to evict people from Indian Village. The village residents were mostly elderly Shoshone women from several families. Only about 20 to 25 people lived there full-time. Some worked for the Park Service or local hotels, but most were unemployed.

By the late 1960s, the Park Service began destroying houses in Indian Village. They did this when residents failed to pay rent or were away for long periods. They used powerful hoses to wash down the adobe houses. Seeing this, Pauline Esteves started organizing her people to fight back. She contacted California Indian Legal Services, a group that helps Native Americans with their rights.

In 1975, the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) took on the Timbisha Shoshone's legal case. NARF lawyers helped organize Esteves' people as a recognized group under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The Bureau of Indian Affairs approved their request in 1977. This official recognition gave the tribe certain rights and powers to fight against the Park Service's evictions.

The next year, Pauline Esteves made an agreement with the Indian Health Service and the National Park Service for a water supply for the village. The tribe also got a loan from the Bureau of Indian Affairs for trailers to replace the old houses. During this time, the Park Service still resisted the tribe's efforts to build permanent homes. The tribe did not yet own the land they lived on. Park Service leaders worried about setting a new rule if they gave land to Native American groups. In 1979, with help from NARF, the Timbisha Shoshone wrote a request for full federal tribal recognition.

How Many Timbisha People Are There?

Historians have made different guesses about how many Native Americans lived in California before Europeans arrived. Alfred L. Kroeber estimated that in 1770, there were about 1,500 Timbisha and Chemehuevi people combined. He thought this number dropped to 500 by 1910.

Official Tribal Recognition

With help from California Indian Legal Services, Timbisha Shoshone members like Pauline Esteves and Barbara Durham started working for a formal reservation in the 1960s. The Timbisha Shoshone Tribe was officially recognized by the U.S. government in 1982. They were one of the first tribes to gain this status through the Bureau of Indian Affairs' Federal Acknowledgment Process.

Tribal Land and Where They Live Now

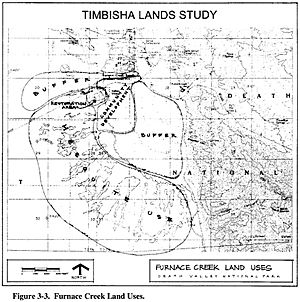

The tribe's reservation, called the Death Valley Indian Community, was created in 1982. At first, it was only the original 40 acres set aside for Indian Village. This land is located within Death Valley National Park at Furnace Creek in Death Valley, Inyo County, California. In 1990, it was still 40 acres in size and had 199 tribal members living there.

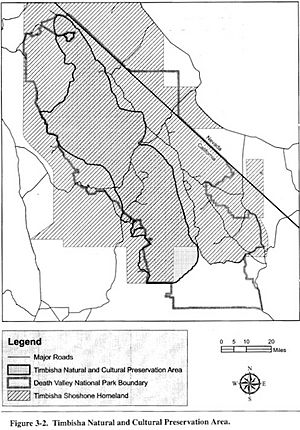

Even with federal recognition and their small reservation, the Timbisha still faced challenges with the Death Valley National Park's National Park Service. They wanted to get more of their ancestral lands back within the Park. After much effort from the tribe, and some federal political work, the Timbisha Shoshone Homeland Act of 2000 finally returned 7,500 acres of their ancestral lands to the Timbisha Shoshone tribe.

Today, the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe has about 300 members. Usually, about 50 of them live at the Death Valley Indian Community at Furnace Creek inside Death Valley National Park. Many members spend their summers in Lone Pine in the Owens Valley to the west.

Timbisha Tribal Name and Groups

The Timbisha Shoshone (Tümpisa Shoshoni) have been known by other names like California Shoshoni, Death Valley Shoshone, or Panamint. The name "Coso" or "Koso," which used to be common, is now less used in favor of Timbisha.

The Timbisha people of Death Valley call themselves Nümü Tümpisattsi. This means "Death Valley People" or "People from the Place of red ochre (face) paint." Death Valley was named after an important source of red ochre. This is a type of clay found in Golden Valley, south of Furnace Creek, California. The clay is called "Tümpisa" and is used to make paint. Sometimes they even called themselves Tsakwatan Tükkatün, which means "Chuckwalla Eaters."

However, they simply call themselves Nümü, which means "Person" or "People."

The Timbisha had names for other tribes too. They called the Kawaiisu people Mukunnümü ("Hummingbird people"). Their northern neighbors, the Eastern Mono (Owens Valley Paiute), were called Kwinawetün ("north place people"). The Western Mono were called Panawe ("western people"). Their neighbors to the west, the Tübatulabal, were known as Waapi(ttsi) ("enemy"). The Yokuts were called Toyapittam maanangkwa nümü ("people on the other (western) side of Sierras"). Their Western and Northern Shoshone relatives were called Sosoniammü Kwinawen (Kuinawen) Nangkwatün Nümü ("Shoshoni speaking northwards people").

In official U.S. government lists, their name is sometimes written as "Timbi-Sha." However, this is a mistake and not correct in the Timbisha language. The tribe never uses a hyphen in its name. Both the California Desert Protection Act and the Timbisha Shoshone Homeland Act spell their name correctly.

The tribe has a website with photos, history, and old documents, including their 1863 treaty. The tribal government has offices in Bishop, California. A large collection of baskets made by tribal members can be seen at the Eastern California Museum in Independence, California.

Historic Timbisha Groups and Areas

Harold Driver recorded two Timbisha subgroups in Death Valley in 1937: the "o'hya" and the "tu'mbica."

Julian Steward identified four main "districts" or groups (süüpantün) of Timbisha Shoshone. Each group had a leader (pokwinapi) and was made up of several family groups (nanümü). These groups were connected by family ties and shared resources. The "districts" were often named after their most important village.

- Little Lake Band: These groups lived around Little Lake, Indian Gardens, Coso Hot Springs, and the Coso Range. Much of their land is now part of the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake.

- Kuhwitsi (People from Little Lake area)

- Koosotsi (People from Coso Hot Springs area)

- Saline Valley Band: These groups lived from the Inyo Mountains in the west to Saline Valley, Eureka Valley, and the Last Chance Range to the east.

- Ko'ontsi (People of Saline Valley)

- Pawüntsitsi (People from the high country between Saline and Eureka Valleys)

- Panamint Valley Band: These groups lived from Panamint Valley north of Ballarat, California eastward to the Panamint Range.

- Haüttantsi (People of Warm Springs and Indian Ranch area of Panamint Valley)

- Kaikottantsi (People of the Panamint Range)

- Death Valley Band: These groups lived from Death Valley north of Furnace Creek, California west to the Funeral Mountains and Amargosa Range, and around Beatty, Nevada.

- Tümpisattsi (People of Furnace Creek and Death Valley)

- Ohyüttsi (People of Mesquite Flats in northern Death Valley)

See also

In Spanish: Timbisha para niños

In Spanish: Timbisha para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |