Sahaptin facts for kids

The Sahaptin are a group of Native American tribes. They all speak different forms of the Sahaptin language. These tribes lived along the Columbia River and its smaller rivers in the Pacific Northwest part of the United States. Some of the Sahaptin-speaking peoples included the Klickitat, Kittitas, Yakama, Wanapum, Palus, Lower Snake, Walla Walla, Umatilla, Tenino, and Nez Perce.

Contents

Where the Sahaptin Lived

Early records show that Sahaptin-speaking people lived in the southern part of the Columbia Basin. This area is in what is now Washington and Oregon. Many villages were found along the Columbia River, from the Cascades Rapids to near Vantage, Washington. They also lived along the Snake River up to the Idaho border. The Nez Perce tribe, who were closely related, lived to the east.

Other villages were located along rivers like the Yakima, Deschutes, and Walla Walla. Some Sahaptin villages were even west of the Cascade mountains in southern Washington. These included villages of the Upper Cowlitz tribe and some Klickitat groups. The western part of Sahaptin land was shared with Chinookan tribes.

Sahaptin Heritage and Connections

The Sahaptin people belong to the same language family as the Nez Perce. They were very good friends with the Nez Perce. However, they often competed with Salishan-speaking tribes to their north. These included the Flathead, Coeur d'Alene, and Spokane. The Sahaptin also had ongoing conflicts with the Blackfeet, Crow, and Shoshoni tribes to the east and south.

The Sahaptin people called themselves Ni Mii Puu. This means "the people" or "we the people." The name Sahaptin or Saptin was a name given to them by Salishan tribes. European Americans later started using this name. When Lewis and Clark explored the area in 1805, they called these people Chopunnish. This might have been another form of the name Saptin. The well-known name for the Nez Percé, "Pierced Noses," was given by French-Canadian trappers. It referred to their old custom of wearing a dentalium shell through a hole in their nose.

In 1805, there were likely more than 6,000 Sahaptin people. During the 1800s, their population dropped a lot. This was mainly because of new diseases brought by outsiders. Other reasons included wars with the Blackfeet, and illnesses like measles and smallpox after miners came in the 1860s. Losses from the 1877 war and later forced moves also played a part. By 1910, their official number was about 1,530.

Sahaptin Daily Life and Culture

The Sahaptin tribes did not have a clan system. Their chiefs were chosen by the people, not born into the role. Chiefs led with the help of a council. Their groups were spread out, and there was no single leader for all tribes.

Homes and Shelters

Their main homes were large buildings shared by many families. These houses were often long and narrow, about 20 feet (6 meters) wide and 60 to 90 feet (18 to 27 meters) long. They had a frame of poles covered with mats made from rushes. Inside, the floor was dug lower than the ground, and earth was piled up around the sides to keep the house warm. An opening in the middle of the roof let smoke escape.

Inside, fires were placed along the center, about 10 to 12 feet (3 to 3.6 meters) apart. Each fire served two families on opposite sides of the house. Sometimes, mat curtains separated the family areas. One house could hold over one hundred people. Lewis and Clark even saw one big enough for nearly fifty families! For short trips, they used tipis made of buffalo skin or shelters made of brush.

They also used sweat-houses. A permanent sweat-house was a shallow hole in the ground, covered with poles and earth, and lined with grass. Young, unmarried men often slept here in winter. They would sometimes create steam by pouring water on hot stones for cleansing ceremonies.

Temporary sweat-houses were also used by both men and women. These had a frame of willow branches covered with blankets. Hot stones were brought inside from fires.

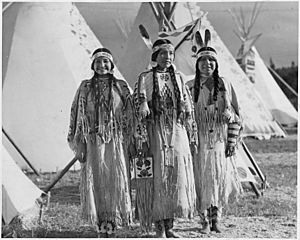

Sahaptin people did not use pottery. They made spoons from deer or bison horn. Women used digging sticks to gather roots. This tool was given to them in a special ceremony when they became adults. Women also prepared and tanned animal skins, sewing and decorating them for clothing. They wore a special basket hat shaped like a fez. Men hunted and fished. They used bows and arrows, lances, shields, and fishing tools. Warriors also wore helmets made of animal skin.

Food Sources

The Sahaptin people were hunter-gatherers, meaning they found their food in nature. Women gathered many wild roots and berries. They sometimes mixed these with cooked meat and dried the mixture for later. Besides fish and game, especially salmon and deer, their main foods were the roots of camas (Camassia quamash) and kouse (Lomatium cous). Camas roots were roasted in pits. Kouse was ground into flour and shaped into cakes for future use. Women were mainly in charge of gathering and preparing these root crops.

Beliefs and Traditions

Marriage usually happened around age fourteen. The wedding included a big feast and gift-giving. It was common for men to have more than one wife, but they could not marry close relatives. Their family system was patriarchal, meaning leadership and inheritance passed through the male line. People believed that the Sahaptin had very high moral standards both before and after marriage.

When someone died, they were buried in the ground. Their personal belongings were placed with them. Their home was either taken down or moved to a new spot. The new house was cleaned in a special ceremony, and rituals were done to make sure no spirits stayed behind. A funeral feast marked the end of the official mourning period. Sickness and death, especially of children, were often thought to be caused by spirits.

Their religion involved believing that spirits were in everything (called animistic). They didn't have many complex myths or ceremonies. A very important event for a boy or girl was the dream vigil. After fasting alone for several days, the child would try to have a vision of a spirit animal. This animal would be their guide and protector throughout life. Dreams were seen as a major way to get spiritual guidance, and children were taught how to understand them. The main ceremony was a dance to honor the spirit guide. The scalp dance was also important.

European missionaries later came to the area. Some Catholic ideas were shared with the Nez Percés by Canadian and Iroquois workers from the Hudson's Bay Company. By 1820, the Nez Percés and Flathead had started to adopt some Catholic practices. Missionaries noted that the Nez Percé seemed open to learning about the Christian faith.

Treaties and Conflicts

In 1855, the Sahaptin people sold a large part of their land through a treaty. During the general conflicts of 1855–56, sometimes called the Yakima War, the Nez Percés mostly remained friendly with the Americans.

In 1863, after gold was discovered, another treaty was made. This treaty was between Nez Percés chief Lawyer (whose group had become Christian and was adapting to white culture) and General Oliver O. Howard of the U.S. Army. Lawyer agreed to give up all their land except for the Lapwai reservation. However, Chief Joseph of the Wallowa group refused to sign this new treaty. He said that the Treaty of 1855 promised to protect their homeland "as long as the sun shines."

Because Nez Percés custom meant no single chief spoke for everyone, Chief Joseph and others (like Toohoolhoolzote and Looking Glass) did not sign the treaty. They believed the U.S. Government was still bound by the original agreement. Only Lawyer's group would be bound by the new treaty they signed.

But General Howard reportedly gathered other Nez Percé people to sign the document. This made it look like Joseph and the other chiefs had agreed to the treaty. So, in the eyes of the U.S. government, they would also have to follow its rules.

Chief Joseph strongly refused to accept the new treaty. He only gave in when it became clear that his people's survival depended on it. But as they made the difficult journey out of their homeland to the new reservation, a small group of young Nez Percés warriors broke away. They killed several white settlers along the Salmon River.

These events led to the Nez Percés war in 1877. For several months, Joseph, Looking Glass, and other chiefs skillfully avoided the U.S. Army troops and many Indian scouts. They retreated north for over a thousand miles across the mountains. However, they were stopped by the U.S. Army close to the Canadian border and forced to surrender.

Even though he was promised he would be returned to his own country, Joseph and the rest of his group were sent to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). So many people died there that in 1885, the few who survived were moved to the Colville Indian Reservation in eastern Washington. Throughout their entire retreat, Joseph's warriors did not commit any cruel acts. The main part of the tribe did not take part in the war.

In 1893, the shared land of the Lapwai reservation was divided among the tribe's families under the Dawes Act. The remaining lands were then sold to white settlers, which meant the Nez Percé lost more of their land.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |