Yakima War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Yakima War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

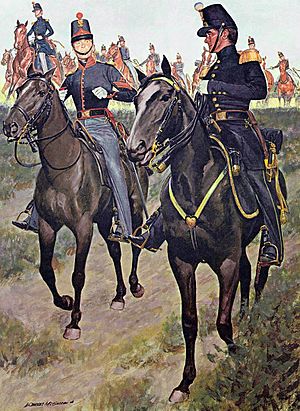

Illustration of U.S. Army artillerymen in 1855 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Snoqualmie |

Yakama Walla Walla Umatilla Nisqually Cayuse Palouse Puyallup Klickitat |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Chief Patkanim |

Chief Kamiakin Chief Leschi Chief Kanaskat |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 4th Infantry Regiment 6th Infantry Regiment 9th Infantry Regiment 3rd Artillery Regiment Washington militia Oregon militia USS Decatur Snoqualmie warriors |

Yakama warriors Walla Walla warriors Umatilla warriors Nisqually warriors Cayuse warriors Palouse warriors Puyallup warriors Klickitat warriors |

||||||

The Yakima War (1855–1858) was a conflict between the United States and the Yakama people. The Yakama are a Native American group from the Northwest Plateau region. At the time, their land was part of the Washington Territory. Other Native American tribes joined both sides of the conflict.

This war mostly happened in what is now southern Washington. Some smaller battles in western Washington and the northern Inland Empire were also part of this larger conflict. These were sometimes called the Puget Sound War and the Palouse War. People also called this conflict the Yakima Native American War of 1855.

Contents

Why Did the Yakima War Happen?

Before the war, the United States made agreements, called treaties, with several Native American tribes in the Washington Territory. In these treaties, the tribes agreed that the U.S. government had power over a large area of land. In return, the tribes were promised:

- Half of the fish in the territory forever.

- Money and supplies.

- Special lands, called reservations, where white settlers could not live.

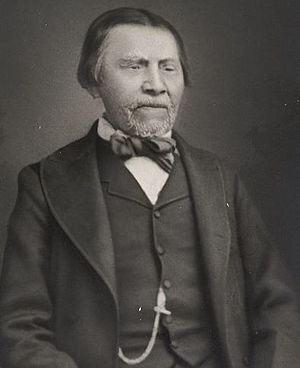

The governor, Isaac Stevens, promised that Native American lands would be safe. However, he could not make this promise official until the U.S. Senate approved the treaties. Meanwhile, people heard that gold was found in Yakama territory. This caused many gold seekers, called prospectors, to rush into the area. They traveled across the newly defined tribal lands without permission. This made Native American leaders very upset. In 1855, two prospectors were killed by Qualchin, who was the nephew of Chief Kamiakin. This happened after the prospectors had harmed a Yakama woman.

How the Fighting Started

The Death of Mosheel’s Family

A group of American miners met two Yakama women, a mother and her daughter, who were traveling with a baby. The miners attacked and killed all three. The husband and father of the women, a Yakama man named Mosheel, gathered two friends, including Qualchin. They found the miners and killed them in their camp.

The Death of Andrew Bolon

On September 20, 1855, Bureau of Indian Affairs agent Andrew Bolon heard about the miners' deaths. He rode out to investigate. A Yakama chief named Shumaway warned him that Qualchin was too dangerous. Bolon listened and started to ride home. On his way, he met a group of Yakama people traveling south and decided to ride with them. Mosheel, Shumaway's son, was in this group.

Bolon told Mosheel that the miners' deaths were wrong and that American soldiers would punish those responsible. Mosheel became angry. He decided Bolon should be killed. Some Yakama in the group disagreed, but Mosheel, who was a leader, insisted. Bolon, who did not speak Yakama, did not know what was being discussed. During a rest stop, as they ate lunch, Mosheel and at least three other Yakama attacked Bolon with knives. Bolon cried out, "I did not come to fight you!" before he was hurt. Bolon's horse was then shot, and his body was burned.

The Battle of Toppenish Creek

When Shumaway heard about Bolon's death, he immediately sent a messenger to the U.S. Army at Fort Dalles. He also wanted his son, Mosheel, arrested and given to the government to prevent American revenge. However, a Yakama council disagreed. They sided with Shumaway's older brother, Kamiakin, who called for war.

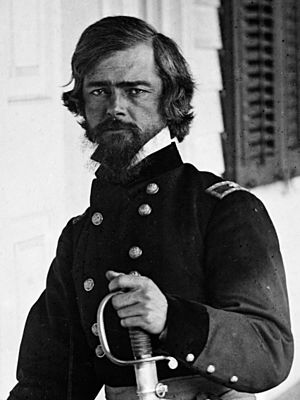

Meanwhile, the army commander, Gabriel Rains, heard the news. He ordered Major Granville O. Haller to lead a group of soldiers from Fort Dalles. Haller's soldiers were met by a large group of Yakama warriors at the edge of their territory. As Haller's group pulled back, the Yakama attacked them at the Battle of Toppenish Creek. The American soldiers were defeated.

The War Spreads

The death of Bolon and the American defeat at Toppenish Creek caused great fear across the territory. People worried that a Native American uprising was happening. This news also made the Yakama people feel stronger, and more tribes joined Kamiakin.

General Rains had only 350 federal soldiers. He asked the acting governor, Charles Mason, for help. Governor Isaac Stevens was away in Washington, D.C., trying to get the treaties approved. Rains asked for two companies of volunteers to join the fight quickly.

Oregon Governor George Law Curry also gathered 800 cavalry soldiers. Some of these soldiers entered Washington territory in early November. With over 700 soldiers, Rains prepared to march toward Kamiakin, who had 300 warriors camped at Union Gap.

Attack on White River Settlements

While Rains gathered his forces, Leschi, a Nisqually chief who was half Yakama, tried to unite the Puget Sound tribes against the government. Leschi started with 31 warriors from his own group. He gathered over 150 Muckleshoot, Puyallup, and Klickitat warriors. Other tribes did not join him. When news spread about Leschi's growing army, a group of 18 volunteer soldiers, called Eaton's Rangers, was sent to arrest him.

On October 27, ranger James McAllister and farmer Michael Connell were attacked and killed by Leschi's men near the White River. The rest of Eaton's Rangers were trapped inside an old cabin for four days before they escaped. The next morning, Muckleshoot and Klickitat warriors attacked three settler cabins along the White River, killing nine people. Many settlers had already left the area because Chief Kitsap of the neutral Suquamish tribe had warned them.

John King, one of four survivors, told about the attack. He was seven years old and, along with two younger siblings, was spared by the attackers. They were told to go west. The King children eventually met a local Native American named Tom.

I told him of the massacre. He said he suspected something of the kind, as he had heard firing in that direction. He told me that I should get the children and take them to his wigwam, adding that 'when the moon was high' he would take us to Seattle in his canoe. His squaw was as kind and amiable as could be, and did all in her power to make it pleasant for us, but the children were very shy. She set out dried fish and whortleberries for our repast, but nothing she could do would induce them to go to her. Our hunger was so great that the various and penetrating odors permeating the food she had brought us was no bar to our relish for it as I remember.

Leschi later said he was sorry for the attack on the White River settlements. After the war, Nisqually people in his group confirmed that Leschi had told off his commanders who planned the attack.

The Battle of White River

Army Captain Maurice Maloney, with 243 soldiers, had been sent east to cross the Naches Pass. He planned to enter Yakama land from the back. But the pass was blocked by snow, so he started returning west after the White River attacks. On November 2, 1855, Leschi's men were seen by Maloney's returning soldiers. They moved back to the White River's right bank.

On November 3, Maloney ordered 100 men under Lt. William Slaughter to cross the White River and fight Leschi's forces. But Native American sharpshooters stopped them. One American soldier was killed. Reports of Native American deaths vary, from one (reported by a Puyallup man named Tyee Dick) to 30 (claimed in Slaughter's report). The lower number might be more accurate. At four o'clock, it was too dark for the Americans to cross. Leschi's men moved back three miles to their camp on the Green River. They were happy they had stopped the Americans. Tyee Dick later said the battle was "lots and lots of fun."

The next morning, Maloney advanced with 150 men across the White River. He tried to attack Leschi at his camp on the Green River. But the difficult land made it impossible, and he quickly called off the attack. Another small fight on November 5 resulted in five American deaths, but no Native American deaths. Maloney could not make progress, so he began to leave the area on November 7. He arrived at Fort Steilacoom two days later.

The Battle of Union Gap

One hundred fifty miles to the east, on November 9, General Rains met Kamiakin near Union Gap. The Yakama had built a stone wall for defense. American cannons quickly destroyed it. Kamiakin had not expected such a large force. The Yakama, thinking they would win easily like at Toppenish Creek, had brought their families. Kamiakin now ordered the women and children to run away while he and his warriors fought to slow down the Americans.

While checking the American lines, Kamiakin and 50 mounted warriors met an American patrol. The patrol chased them. Kamiakin and his men escaped across the Yakima River. The Americans could not keep up, and two soldiers drowned before the chase ended.

That evening, Kamiakin held a war meeting. They decided the Yakama would make a stand in the hills of Union Gap. Rains began moving toward the hills the next morning. Small groups of Yakama used quick attacks to slow the American advance. At four in the afternoon, Major Haller, with cannon support, led a charge against the Yakama position. Kamiakin's forces scattered into the bushes near Ahtanum Creek, and the American attack was called off.

In Kamiakin's camp, they planned a night attack against the Americans but decided not to. Instead, early the next day, the Yakama continued to retreat defensively. This tired the American soldiers, who eventually stopped fighting. On the last day of fighting, the Yakama had only one death: a warrior killed by U.S. Army Indian Scout Cutmouth John.

Rains continued to Saint Joseph's Mission, which was empty because the priests had fled with the Yakama. Soldiers found a barrel of gunpowder there. They wrongly thought the priests had been secretly giving weapons to the Yakama. The soldiers rioted, and the mission was burned down. With snow starting to fall, Rains ordered his soldiers to return to Fort Dalles.

Skirmish at Brannan's Prairie

By the end of November, federal soldiers were back in the White River area. A group of soldiers, led by Lt. Slaughter, and militia, led by Capt. Gilmore Hays, searched the area. They fought Nisqually and Klickitat warriors at Biting's Prairie on November 25, 1855. Several people were hurt, but there was no clear winner. The next day, a Native American sharpshooter killed two of Slaughter's soldiers. Finally, on December 3, as Slaughter and his men camped for the night on Brannan's Prairie, they were fired upon, and Slaughter was killed. News of Slaughter's death greatly saddened settlers in the main towns. Slaughter and his wife were a popular young couple, and the government paused for a day of mourning.

Disagreements Among Leaders

In late November 1855, General John E. Wool arrived from California and took charge of the U.S. side of the conflict. His main office was at Fort Vancouver. Wool was seen as proud and bossy. Some people criticized him for blaming white settlers for many of the conflicts between Native Americans and white people in the west. After looking at the situation in Washington, he thought that chasing Yakama groups around the territory would lead to defeat. Wool planned a different kind of war. He wanted the local militia to protect the main settlements. Then, better-trained U.S. Army soldiers would move in and take over traditional Native American hunting and fishing grounds. This would force the Yakama to surrender by making them hungry.

However, Oregon Governor Curry decided to attack the eastern tribes first. These tribes were the Walla Walla, Palouse, Umatilla, and Cayuse. They had stayed neutral until then. Curry believed it was only a matter of time before they joined the war, so he wanted to attack first. Oregon militia, led by Lt. Col. James Kelley, entered the Walla Walla Valley in December. They fought with the tribes and captured Peopeomoxmox and other chiefs. Now, the eastern tribes were fully involved in the war. General Wool blamed Governor Curry for this.

Meanwhile, on December 20, Washington Governor Isaac Stevens finally returned to the territory. He had a dangerous journey through the Walla Walla Valley. Stevens was unhappy with Wool's plan to wait until spring to continue military actions. He also learned about the attack on the White River settlements. Stevens told the Washington Legislature that "the war shall be prosecuted until the last hostile Indian is exterminated." Stevens was also angry that he did not have a military escort during his dangerous trip through Walla Walla. He accused Wool of "criminal neglect of my safety." Oregon Governor Curry also demanded that Wool be removed from his position. (This disagreement ended in the fall of 1856, and Wool was moved to command the Eastern Department.)

1856

The Battle of Seattle

In late January 1856, Governor Stevens arrived in Seattle by ship to calm the town's citizens. Stevens confidently said that "New York and San Francisco will as soon be attacked by the Indians as the town of Seattle." But even as Stevens spoke, a large Native American army of 6,000 was moving toward the town. As the governor's ship sailed away, members of some neutral Puget Sound tribes came into Seattle. They asked for safety from a large Yakama war party that had just crossed Lake Washington. The danger was confirmed when Princess Angeline arrived. She brought news from her father, Chief Seattle, that an attack was coming. Doc Maynard began moving women and children from the neutral Duwamish tribe by boat to the west side of Puget Sound. A group of citizen volunteers, led by the Marines from the nearby ship USS Decatur, started building a blockhouse.

On the evening of January 24, 1856, two scouts from the Native American forces, dressed in disguise, entered Seattle to gather information. Some people believe one of these scouts might have been Leschi.

Just after sunrise on January 25, 1856, American lookouts saw a large group of Native Americans approaching the settlement hidden by trees. The USS Decatur began firing into the woods. This made townspeople hurry to the blockhouse. The tribal forces, which some accounts say included Yakama, Walla Walla, Klickitat, and Puyallup warriors, fired back with small guns. They quickly moved toward the settlement. But the constant firing from the Decatur's guns forced the attackers to pull back and regroup. They then decided to stop the attack. Two Americans were killed in the fighting, and 28 Native Americans died.

Snoqualmie Operations

To block the passes across the Cascade Mountains and stop more Yakama movements into western Washington, a small fort was built at Snoqualmie Pass in February 1856. Fort Tilton opened in March 1856. It had a blockhouse and several storage buildings. A small group of volunteers manned the fort, supported by 100 Snoqualmie warriors. This was part of an agreement made by the powerful Snoqualmie chief Patkanim with the government the previous November.

Meanwhile, Leschi had successfully fought off and avoided earlier American attempts to defeat his forces along the White River. Now, he faced a third attack. As Fort Tilton was being built, Patkanim, who was made a captain in the Volunteers, led 55 Snoqualmie and Snohomish warriors to capture Leschi. A newspaper in Olympia, the Pioneer and Democrat, proudly announced their mission with the headline "Pat Kanim in the Field!"

Patkanim tracked Leschi to his camp along the White River. But a planned night attack was stopped when a barking dog alerted the guards. Instead, Patkanim got close enough to Leschi's camp to speak. He told the Nisqually chief, "I will have your head." Early the next morning, Patkanim began his attack. The fierce fight reportedly lasted ten hours and only ended when the Snoqualmie ran out of bullets.

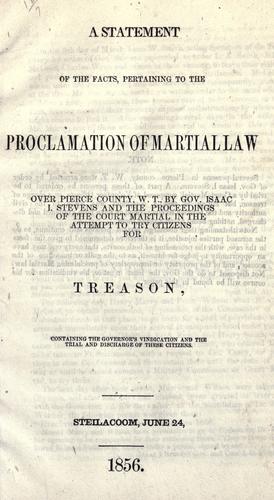

Martial Law Declared

By the spring of 1856, Governor Stevens began to suspect that some settlers in Pierce County, who had married into local tribes, were secretly helping their Native American relatives against the government. Stevens may have distrusted these settlers more because Pierce County had strong support for the Whig Party, which opposed the Democratic policies Stevens supported. Stevens ordered the suspected farmers arrested and held at Camp Montgomery. When Judge Edward Lander ordered their release, Stevens declared martial law in Pierce and Thurston counties. This meant the military took control. On May 12, Judge Lander ruled that Stevens had ignored the court. Marshals sent to Olympia to arrest the governor were thrown out of the capitol, and Stevens ordered Judge Lander's arrest by the militia.

When Francis A. Chenoweth, the chief justice of the territorial supreme court, learned of Lander's arrest, he left Whidbey Island and traveled by canoe to Pierce County. In Steilacoom, Chenoweth reopened the court. He prepared to again issue orders to release the settlers. Stevens sent militia to stop the chief justice. But the troops were met by the Pierce County Sheriff, whom Chenoweth had ordered to gather a group of citizens to defend the court. The standoff ended when Stevens agreed to back down and release the farmers.

Stevens later pardoned himself for ignoring the court. However, the United States Senate called for him to be removed from his position. The Secretary of State also criticized him, writing that "... your conduct, in that respect, does not therefore meet with the favorable regard of the President."

The Cascades Massacre

The Cascades Massacre happened on March 26, 1856. It was an attack by several tribes against white soldiers and settlers at the Cascades Rapids. The attackers included warriors from the Yakama, Klickitat, and Cascades tribes (now known as Wasco tribes). Fourteen settlers and three U.S. soldiers died in this attack. These were the most losses for U.S. citizens during the Yakima War. The United States sent more soldiers the next day to defend against further attacks. The Yakama people fled. However, nine Cascades Indians who surrendered, including Chenoweth, Chief of the Hood River Band, were wrongly charged and executed.

Puget Sound War

The U.S. Army arrived in the region in the summer of 1856. That August, Robert S. Garnett oversaw the building of Fort Simcoe as a military base. At first, the conflict was only with the Yakama. But eventually, the Walla Walla and Cayuse tribes were drawn into the war. They carried out several attacks and battles against the American soldiers.

Coeur d'Alene War

The last part of the conflict, sometimes called the Coeur d'Alene War, happened in 1858. General Newman S. Clarke was in charge of the Department of the Pacific. He sent soldiers under Col. George Wright to deal with the recent fighting. At the Battle of Four Lakes near Spokane, Washington in September 1858, Wright strongly defeated the Native Americans. He called a meeting of all the local Native Americans at Latah Creek (southwest of Spokane). On September 23, he made a peace treaty. Under this treaty, most of the tribes had to go to reservations.

What Happened After the War?

As the war ended, Kamiakin fled north to British Columbia. Leschi was tried twice for murder by the government. His first trial ended with a hung jury (the jury could not agree). He was found guilty in the second trial and then executed outside Fort Steilacoom. The U.S. Army refused to let him be executed on Army land because military leaders considered him a lawful combatant (a soldier in a war). In 2004, a special Historical Court in Washington State agreed with the Army's view and officially cleared Leschi of murder after his death.

U.S. Army Native American scouts found and captured Andrew Bolon's attackers, who were later executed.

Snoqualmie warriors were sent to hunt down remaining enemy forces. The government agreed to pay them for scalps. However, this practice was quickly stopped by the government auditor. Questions arose about whether the Snoqualmie were actually fighting enemies or killing their own slaves.

The Yakama people were forced to live on a reservation south of the city of Yakima.

Images for kids

-

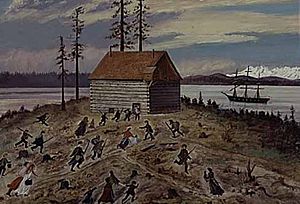

Seattleites move to the town blockhouse as USS Decatur fires on approaching tribal forces.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |