Isaac Stevens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

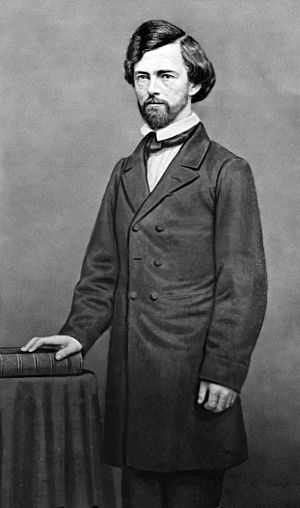

Isaac Ingalls Stevens

|

|

|---|---|

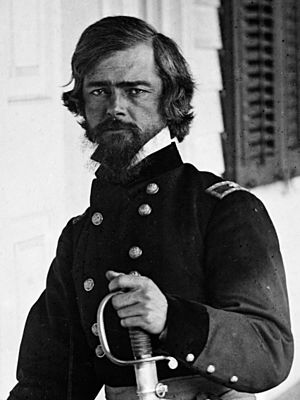

Isaac Ingalls Stevens during the American Civil War

|

|

| 1st Governor of Washington Territory | |

| In office November 25, 1853 – August 11, 1857 |

|

| Appointed by | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Fayette McMullen |

| Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives from Washington Territory's at-large district | |

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 3, 1861 |

|

| Preceded by | James Patton Anderson |

| Succeeded by | William H. Wallace |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 25, 1818 North Andover, Massachusetts |

| Died | September 1, 1862 (aged 44) Chantilly, Virginia |

| Resting place | Island Cemetery, Newport, Rhode Island |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Margaret Hazard Stevens |

| Relations | Oliver Stevens (brother) |

| Children | 5 (including Hazard Stevens) |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Profession | Soldier |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1839–1853 1861–1862 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 79th New York Infantry Rgt. 1st Division, IX Corps |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War Yakima War American Civil War |

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (born March 25, 1818 – died September 1, 1862) was an American soldier and politician. He was the first governor of Washington Territory from 1853 to 1857. Later, he represented Washington Territory in the United States House of Representatives. During the American Civil War, he led several Union Army groups. He died in battle at Battle of Chantilly, bravely carrying his regiment's flag. President Abraham Lincoln was reportedly thinking about giving him command of the Army of Virginia at the time of his death. After he died, he was given the higher rank of Major General. Many schools, towns, counties, and lakes are named in his honor.

Stevens came from early American families in New England. He was only 5 ft 3 in (1.60 m) tall. He graduated at the top of his class from West Point. He then had a successful military career. As governor of Washington Territory, he was a strong and sometimes controversial leader. Some people praised him, while others criticized him. One historian said that more has been written about Stevens than almost all the rest of the territory's history in the 1800s. Stevens tried to make peace with Native American tribes to avoid fighting. However, when the Yakama War started because Native Americans resisted settlers, he fought hard. He used martial law, put judges in jail who disagreed with him, and created his own army. This led to him being found guilty of disrespecting the court, but he famously pardoned himself. The President of the United States also criticized him. Still, his strong decisions during tough times were both praised by his supporters and noted by historians.

Isaac Stevens was the father of Hazard Stevens. Hazard was a hero in the Battle of Suffolk. He was also one of the first people to climb to the top of Mount Rainier.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Isaac Stevens was born in North Andover, Massachusetts. His parents were Isaac Stevens and Hannah Stevens. His mother's family were early Puritan settlers. They were a respected family with many clergy and military members. As a young man, Isaac was very smart, especially in math. He was short, standing 5 ft 3 in (1.60 m) tall as an adult. This might have been due to a problem with a gland.

Stevens did not get along with his father, who was described as a "stern taskmaster." His father's demands pushed him very hard. Once, while working on the family farm, Stevens almost died from sunstroke. After his mother died in a carriage accident, his father remarried a woman Stevens disliked. Stevens said he almost had a mental breakdown when he was young.

Stevens graduated from Phillips Academy, a prep school for boys, in 1833. He was accepted into the United States Military Academy at West Point. He graduated in 1839 as the top student in his class.

Military Career and Achievements

Stevens was a key officer in the Corps of Engineers during the Mexican–American War. He fought in major battles like the Siege of Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Contreras, and Churubusco. In the fight at Churubusco, his leaders noticed his bravery. He was given the special rank of brevet captain. He was honored again for his bravery at the Battle of Chapultepec, this time becoming a brevet major. Stevens also fought at Molino del Rey and the Battle for Mexico City. He was badly wounded in Mexico City. Later, he wrote a book about his experiences called Campaigns of the Rio Grande and Mexico (1851).

From 1841 to 1849, he oversaw the building of forts along the New England coast. He then led the coast survey office in Washington, D.C., until March 1853.

Governor of Washington Territory (1853–1857)

Stevens strongly supported Franklin Pierce for President of the United States in 1852. Both men had served in the Mexican–American War. President Pierce rewarded Stevens on March 17, 1853, by naming him governor of the new Washington Territory. This job also made him the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the region. Stevens decided to take on another important task as he traveled west. The government wanted a surveyor to map a good railroad route across the northern United States. This railroad would help open up trade with Asia. With his engineering skills and likely help from President Pierce and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, Stevens won the job.

His group, which included Dr. George Suckley, John Mullan, and Fred Burr, spent most of 1853 slowly surveying the land to Washington Territory. There, Stevens met George McClellan's group, who had surveyed the area between the Puget Sound and the Spokane River. Stevens began his job as governor in Olympia in November 1853.

After his journey, Stevens wrote a third book. It was called Report of Explorations for a Route for the Pacific Railroad near the 47th and 49th Parallels of North Latitude, from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Puget Sound. The United States Congress ordered and published this two-volume report between 1855 and 1860.

Stevens was a controversial governor. Historians still debate his actions. He used strong methods to make Native American tribes in Washington Territory sign treaties. These treaties gave most of their lands and rights to Stevens' government. Some of these treaties included the Treaty of Medicine Creek, Treaty of Hellgate, Treaty of Neah Bay, Treaty of Point Elliott, Point No Point Treaty, and Quinault Treaty. During this time, the Governor used martial law. This helped him enforce his will on both Native Americans and white settlers who disagreed with him. The political and legal fights that followed soon became more important than the Native American war.

Stevens used his troops to fight the Yakama tribe in a harsh winter campaign. This was led by Chief Kamiakin. Also, the execution of the Nisqually chieftain Leschi caused many people to ask President Pierce to remove Stevens. Two people spoke out strongly against Stevens: Judge Edward Lander and citizen Ezra Meeker. While Meeker was not listened to, Lander was arrested by Stevens' forces. President Pierce did not remove Stevens, but he did send a message saying he disagreed with the governor's actions. Most white settlers in Washington Territory felt Stevens was on "their side." They thought Meeker was too sympathetic to Native Americans. So, opposition to Stevens eventually faded.

Because of this public support, Stevens was popular enough to be elected as the territory's representative to the United States Congress in 1857 and 1858. The conflicts between white settlers and Native Americans were left for others to solve. Stevens is often blamed for later conflicts in eastern Washington and Idaho. This includes the war fought by the United States against Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce tribe. These events happened decades after Stevens left Washington State for good in 1857.

Martial Law and Legal Battles

In January 1856, Governor Stevens told the territorial House of Representatives in Olympia that "war shall be prosecuted until the last hostile Indian is exterminated." Historians are not sure if this meant he wanted to wipe out all Native Americans or just those fighting against the settlers.

In April 1856, Governor Stevens removed settlers he thought were helping the enemy. Many of these settlers had married into local tribes. He put them in military custody. Governor Stevens declared martial law in Pierce County to hold military trials for these settlers. He then declared martial law in Thurston County. However, only the territorial legislature had the power to declare martial law. Representatives fought Stevens' attempt to take away their power. A difficult political and legal battle followed.

Stevens had to cancel his declaration of martial law. He also had to fight calls for his removal from office. He decided to use martial law because he wanted to enforce a policy of building blockhouses. This was part of the war against the Native Americans in the Puget Sound region. Native American raids on scattered settlements and an attack on Seattle in February 1856 made Governor Stevens believe he needed to focus on defense. He had a limited number of men. He decided that the white population should gather at strong, protected places. So, volunteers under Stevens' command built forts and blockhouses along the Snoqualmie, White, and Nisqually rivers. Once these were finished, Stevens ordered settlers to leave their homes and stay in these safer areas temporarily.

When Stevens declared martial law, it created a big new problem. On May 11, 1856, lawyers George Gibbs and H. A. Goldsborough wrote a letter to the Secretary of State. They said the war situation, especially in Pierce County, was not as bad as Governor Stevens claimed when he declared martial law. They said Stevens' accusations against certain settlers were only based on suspicion. They stated that the only real evidence was that on Christmas Day, a group of Native Americans had visited a settler's cabin and forced him to give them food.

The territory's law said the governor was the "commander-in-chief of the militia." But there was no official militia. Stevens used his power by controlling local volunteer troops. These troops were formed to meet the needs of the situation. However, neither the federal government nor the territorial legislature had authorized them. Stevens' role as Superintendent of Indian Affairs gave him broad administrative power, but no direct military power. On May 24, 1856, after Judge Chenoweth ruled that Stevens had no legal power to declare martial law, Governor Stevens canceled his martial law orders in Pierce and Thurston counties.

Civil War Service and Death

After the American Civil War began in 1861, Stevens joined the Army again. This happened after the Union Army lost the First Battle of Bull Run. He became a Colonel of the 79th New York Volunteers, also known as the "Cameron Highlanders." He was promoted to brigadier general on September 28, 1861. He fought at Port Royal. He led the Second Brigade of the Expeditionary Forces that attacked the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. He led a division at the Battle of Secessionville. In this battle, he led an attack on Fort Lamar, where 25% of his men were killed or wounded.

Stevens' IX Corps division was moved to Virginia. There, he served under Major General John Pope in the Northern Virginia Campaign and the Second Battle of Bull Run. He was killed in action at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862. He died after picking up the fallen flag of his old regiment. He shouted, "Highlanders, my Highlanders, follow your general!" He charged with his troops, carrying the flag of Saint Andrew's Cross. A bullet hit him in the temple, and he died instantly.

He was buried in Newport, Rhode Island at Island Cemetery. In March 1863, he was given a higher rank after his death. He was promoted to major general, with the promotion dated back to July 18, 1862.

Stevens was married. His son, Hazard Stevens, became a career officer. He was also injured in the Battle of Chantilly. Hazard survived and later became a general in the U.S. Army and an author. With P. B. Van Trump, he made the first recorded climb of Mount Rainier in Washington State.

Death on the Battlefield

A strong thunderstorm and constant Confederate gunfire had slowed the 79th New York Regiment. Five soldiers who carried the regimental flag had already died leading the charge. When Stevens saw another soldier carrying the flag get shot, he ran from the back of his men. He grabbed the flag from the wounded soldier. Witnesses said the injured flag bearer yelled, "for God's sake, General, don't take the colors!" He knew the flag would be a target.

Stevens ignored him and took the flag. At that moment, his own son Hazard, who was in the regiment, was shot and injured by Confederate fire. Hazard Stevens called out to his father for help. The general replied, "I can't attend to you now, Hazard. Corporal Thompson, see to my boy." Stevens then turned to his men and yelled, "Follow your General!" He faced the Confederate line, waving the flag he had just picked up. Stevens charged the Confederate positions, with his men following closely. This new attack forced the defending Louisiana soldiers to retreat into the woods.

Stevens led his men over the abandoned Confederate defenses, chasing the retreating forces into the forest. At that moment, a Confederate bullet hit Stevens in the head, killing him instantly. As he fell, his body twisted, wrapping itself in the flag he was still holding. His blood stained the flag. A newspaper report from that time said Stevens' body was found an hour after he died, his hands still tightly holding the flag pole.

He was buried in Island Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island.

Legacy and Memorials

Historical Reputation

Historians see Stevens as a complex person. According to historian David Nicandri, the four years Stevens governed Washington are studied more than almost all the rest of the territory's official history until Washington became a state in 1889. Accounts of Stevens' time as governor have been very different. Some have "condemned" him, while others have "uncritically applauded" him. Ezra Meeker, a historian and settler who disagreed with Stevens, said he would "take no counsel, nor brook opposition to his will."

Posthumous Promotion

In March 1863, President Abraham Lincoln asked the United States Senate to promote Stevens after his death. He was promoted to Major General. According to George Cullum's Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, "at the very hour of his death, the President and Secretary of War were considering the advisability of placing Stevens in command of the Army in which he was serving."

Memorials and Honors

A marker at Ox Hill Battlefield Park, where the Battle of Chantilly took place, shows the approximate spot where Stevens died leading his men.

In Washington state, Stevens County is named after him. So is Lake Stevens. Several public schools in Washington are also named in his honor. These include Seattle's Isaac I. Stevens Elementary School, Port Angeles' Stevens Middle School, and Pasco's Isaac Stevens Middle School. The Washington State University dormitory Stevens Hall is also named for him. The Washington chapter of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War is called Isaac Stevens Camp No. 1.

Also, Stevensville, Montana, Stevens County, Minnesota, and Idaho's Stevens Peak, Upper Stevens Lake, and Lower Stevens Lake are named in tribute to Stevens.

The United States Army used to have two military bases named after Stevens: Fort Stevens in Washington, D.C., and Fort Stevens in Oregon.

Biographies

Hazard Stevens wrote a book about his father called The Life of Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1900). Kent Richards' book, Isaac I. Stevens: Young Man in a Hurry (1979), is still available today.

Hall of Fame

In 1962, Isaac Stevens was added to the Hall of Great Westerners at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

See also

In Spanish: Isaac Stevens para niños

In Spanish: Isaac Stevens para niños

- History of Olympia, Washington

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |