Ezra Meeker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ezra Meeker

|

|

|---|---|

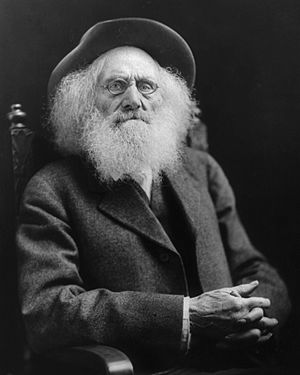

Meeker in 1921

|

|

| 1st Mayor of Puyallup, Washington | |

| In office August 1890 – January 1891 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | James Mason |

| In office January 1892 – January 1893 |

|

| Preceded by | James Mason |

| Succeeded by | L. W. Hill |

| 1st Postmaster of Puyallup, Washington Territory | |

| In office 1877–1882 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Marion Meeker |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Ezra Manning Meeker

December 29, 1830 Butler County, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | December 3, 1928 (aged 97) Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

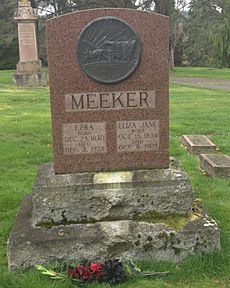

| Resting place | Woodbine Cemetery, Puyallup, Washington, U.S. 47°10′14″N 122°18′8″W / 47.17056°N 122.30222°W |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Eliza Jane Sumner

(m. 1851; |

| Children | 6 |

| Residence | Meeker Mansion |

| Occupation | Farmer |

| Signature | |

| Nicknames |

|

Ezra Morgan Meeker (December 29, 1830 – December 3, 1928) was a famous American pioneer. When he was a young man, he traveled the long Oregon Trail in an ox-drawn wagon. He moved from Iowa all the way to the Pacific Coast. Later in his life, he worked hard to make sure people remembered the Oregon Trail. He even traveled the Trail again many times, just like he did when he was young. Ezra Meeker was also known as the "Hop King of the World" because of his successful farm. He was the first mayor of Puyallup, Washington.

Ezra Meeker was born in Butler County, Ohio. His family moved to Indiana when he was a boy. In 1851, he married Eliza Jane Sumner. The next year, they set off for the Oregon Territory with their new baby son and Ezra's brother. They wanted to find free land to settle on. Their journey on the Trail was very hard and took almost six months, but everyone in their group survived.

The Meekers first stayed near Portland. Then they moved north to the Puget Sound region. In 1862, they settled in what is now Puyallup. There, Ezra Meeker grew hops, which are used to make beer. By 1887, his hop business made him very rich. His wife even built a huge house for their family. But in 1891, tiny bugs called hop aphids destroyed his crops. This caused him to lose most of his money. After that, he tried many different businesses. He even went to the Klondike four times, hoping to make money from the gold rush by selling groceries. These trips were mostly not successful.

Ezra Meeker became worried that people were forgetting the Oregon Trail. He decided to bring attention to it so it could be marked with monuments. From 1906 to 1908, when he was in his late 70s, he traveled the Oregon Trail again by wagon. He wanted to build monuments in towns along the way. His journey took him all the way to New York City. In Washington, D.C., he even met President Theodore Roosevelt. He traveled the Trail several more times in his last twenty years. This included another oxcart trip from 1910 to 1912, and even by airplane in 1924! During another trip in 1928, Meeker became sick. Henry Ford helped him get better. When he returned to Washington state, Meeker got sick again and passed away on December 3, 1928. He was 97 years old. Ezra Meeker wrote several books about his experiences. His work to preserve the Trail is continued by groups like the Oregon-California Trails Association.

Contents

Ezra Meeker's Early Life

Ezra Morgan Meeker was born on December 29, 1830. This was in Butler County, Ohio, near a place called Huntsville. His parents were Jacob and Phoebe Meeker. His family had lived in New Jersey for a long time. Many of his relatives fought for the United States in the American Revolutionary War. Ezra was the fourth of six children.

In 1839, his family moved from Ohio to Indiana. Ezra and his older brother Oliver walked about 200 miles behind the family wagon! Ezra didn't go to school much, maybe only for six months in total. His mother saw that he loved being outdoors more than studying. So, she let him earn money by doing small jobs. He worked at a newspaper called the Indianapolis Journal. His job was to deliver newspapers to people, including a local pastor named Henry Ward Beecher.

In 1845, Ezra's grandfather gave his mother $1,000. This was enough money to buy a farm for the family. Both Jacob and Ezra realized that Ezra enjoyed farm work. So, Jacob put Ezra in charge of the farm. This allowed his father to work as a miller.

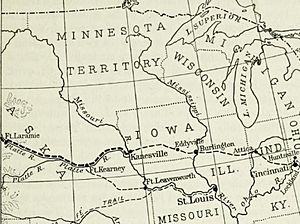

Journey to Oregon (1852)

Ezra Meeker married his childhood sweetheart, Eliza Jane Sumner, in May 1851. They wanted to start their own farm. In October 1851, they moved to Eddyville, Iowa, and rented a farm. They had heard that land there was free, but it wasn't. Ezra didn't like Iowa's cold winters, and neither did his wife, who was expecting a baby.

Stories were spreading about free land and good weather in the Oregon Territory. Ezra's brother, Oliver, also encouraged them to go. Oliver had already prepared for the trip to Oregon. Ezra and Eliza Jane thought about it for a while. In April 1852, after their son Marion was born, they decided to travel the Oregon Trail.

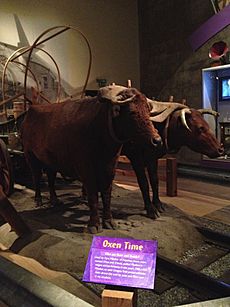

That April, Ezra, Eliza Jane, Oliver, and baby Marion started their journey to Oregon. It was about 2,000 miles long. They had a wagon pulled by two pairs of oxen and one pair of cows. They also had an extra cow. A friend named William Buck joined them. He helped prepare the wagon, and the Meekers carefully packed food. Their group of wagons traveled together, but there wasn't one leader for everyone.

More friends joined them before they left Iowa. They crossed the Missouri River at a small town called Kanesville (now Council Bluffs, Iowa). Ezra felt like he was leaving the United States behind. As they traveled west along the Platte River in Nebraska Territory, there were so many people. They could always see thousands of other pioneers heading west that year. Sometimes, many wagons traveled side by side.

The Meekers moved slowly and steadily. Many others rushed, but their wagons often broke down. Their oxen also died because they weren't cared for properly. Sickness was always a risk. Near Kearney, Nebraska, Oliver Meeker became very ill. Most of Oliver's friends left them, refusing to wait. Oliver got better after four days. Ezra later guessed that one out of ten people on the Trail died during the trip. Ezra remembered seeing one wagon train moving east. They had reached Fort Laramie (in Wyoming today) but had lost all their men. The women and children were turning back, hoping to return home. He never knew if they made it. These deaths made a big impact on young Ezra.

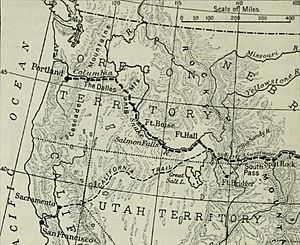

They met Native Americans. Sometimes, the Native Americans asked for supplies to let them pass. But no supplies were given, and there was never any violence. The travelers also hunted bison for food. Bison were a danger too, as their stampedes could destroy wagons. In Idaho, the California Trail split from the Oregon Trail. Buck and some others left the group to go to California. They remained friends with Meeker for life.

Ezra found that the last part of the journey was the hardest. This was between Fort Boise and The Dalles. This section had mountains and deserts, and it was hard to find more food. Many people died here if their animals were tired or they didn't have enough supplies. Others threw away their belongings to make their loads lighter. Some tried to float down the Snake and Columbia Rivers, but many drowned in the fast water.

At The Dalles, they could take a boat to Portland. The Meeker group found many other travelers there. With money Ezra earned from a ferry, they booked passage downriver. Oliver Meeker took the animals overland. They all met in Portland on October 1, 1852. That night, they slept inside a house for the first time since leaving Iowa. Ezra Meeker had lost 20 pounds and only had $2.75 left. Everyone in their group survived the journey. Only one cow was lost while crossing the Missouri River. Ezra Meeker felt that this journey on the Oregon Trail helped him become a man.

Life as a Pioneer

Early Days in the Pacific Northwest

Ezra Meeker's first job in the Pacific Northwest was unloading a ship in Portland. He then moved to St. Helens. His brother Oliver rented a house for workers there, and Ezra helped him. Ezra and his wife still wanted to farm. When the work stopped, he went to find good land to grow crops.

In January 1853, Meeker claimed land about 40 miles downriver from Portland. This is where Kalama, Washington is today. He built a log cabin and started his first farm. He built it away from the water, which was lucky. A big flood happened on the Columbia River soon after. Ezra made money by selling logs that the river left on his land. He also cut down trees to sell for lumber.

In April 1853, Meeker heard that the land north of the Columbia River would become a new territory. It would be called Washington Territory. Its capital would be on Puget Sound. He decided to travel north with his brother to look for land there. At that time, only about 500 people of European descent lived in the Puget Sound area. Most of them were in Olympia, which became the capital. Even with few settlers, there was a lot of activity. Lumber from Puget Sound was used to build San Francisco.

The Meekers' first look at Puget Sound wasn't great. The tide was out, showing muddy areas. But they kept going. They built a small boat to travel by water. Friendly Native Americans met them. They sold them clams and showed them how to cook them. With a Native American guide, they explored the area. They looked for good farmland. They even went into the Puyallup River area, where no white settlers lived. They camped where Puyallup is now. But there were too many huge trees, which would be hard to clear for farming.

They decided on land on McNeil Island. This was close to the busy town of Steilacoom. They could sell their farm goods there. Oliver stayed on the island to build a cabin. Ezra went back to get his family and belongings. He also sold their old land in Kalama. He returned to a cabin with a glass window looking over the water to Steilacoom. They could even see Mount Rainier. Ezra Meeker's land claim later became the site of a prison.

Later in 1853, Ezra and Oliver Meeker got a letter from their father. He said he and other family members wanted to move west. They would come if Oliver returned to help them. The brothers quickly replied that Oliver would go back to Indiana. They put their plans on hold to prepare for his trip by steamship and train. In August 1854, Ezra heard his relatives were on their way. But they were delayed and low on supplies. He quickly went to help them. He planned to guide them through the Naches Pass to Puget Sound. When he found his family near Fort Walla Walla, he learned that his mother and a younger brother had died on the Trail. He guided the survivors through the pass to his land on McNeil Island.

Jacob Meeker didn't see much future on the island. So, the family claimed land near Tacoma. They also ran a general store in Steilacoom. On November 5, 1855, Ezra Meeker claimed 325 acres of land. He called it Swamp Place, near Fern Hill, southeast of Tacoma. He started to improve the land, planting a garden and an orchard.

In 1854, a treaty was signed with the local Native Americans. This treaty restricted them to small reservations. In 1855, the Puget Sound War started. This caused trouble in the area for two years. Ezra Meeker had good relationships with the Native Americans. He didn't fight in the war. In 1895, Meeker helped bring people to a special reburial for a Native American leader named Leschi. In 2004, the Washington State Senate said that Leschi had been treated unfairly.

The "Hop King of the World"

Ezra Meeker's farm at Swamp Place didn't do well. The land was too poor for crops. The family kept running the store in Steilacoom. On January 5, 1861, Oliver Meeker drowned. His ship sank off the California coast while he was returning from a buying trip. The Meekers had borrowed money for the trip. This disaster made Ezra Meeker almost poor. He got land in the Puyallup Valley and moved his wife and children there in 1862. He earned money by helping others clear their land. His father and other brother, John, also had land in the valley. Ezra Meeker ran for the Washington Territorial Legislature in 1861 but lost.

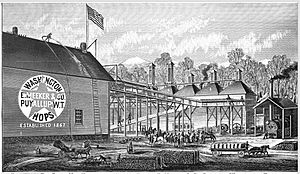

In 1865, a brewer from Olympia named Isaac Wood brought some hop roots from the United Kingdom. He hoped they would grow well in the Pacific Northwest. Hops are used to flavor beer. Since hops weren't grown locally, it was expensive to bring them from far away. Wood hoped local farmers would grow them. He was a friend of Jacob Meeker and gave him some roots to plant. Jacob gave some to Ezra. The plants grew very well! At the end of the season, the Meekers earned $185 from selling their hops to Wood. This was a lot of money back then. Soon, many people started growing hops. Ezra Meeker had a head start. He expanded his hop farms and eventually had 500 acres of land for hops. He also built one of the first hop-drying buildings in the valley. For years, he supplied a famous brewer named Henry Weinhard.

The rich soil and mild weather in the valley were perfect for hops. The plants grew very well, and farmers got four or five times more hops than usual. Ezra Meeker, always looking for a chance, started his own business to buy and sell hops. In 1870, he wrote a pamphlet (a small book) to encourage people to invest in the region. He traveled to San Francisco, then east by the new transcontinental railroad. He wanted to convince railroads to expand to his area. He met with a newspaper editor named Horace Greeley and a railroad owner named Jay Cooke. Cooke bought Meeker's pamphlets to give to possible investors. He even hired Meeker to promote his railroad. While working in Manhattan, Meeker dressed like a city person. But he still kept some of his frontier habits, like stirring butter into his coffee.

In 1877, Meeker planned out a town around his cabin. He named the town Puyallup. He said it meant "generous people" in the local Native American language. The local post office was called "Franklin," a common name. Meeker, who was the town's first postmaster, said the new name would be unique. He later admitted that people in England had trouble saying "Puyallup." It's still hard for people who aren't from the area!

Meeker worked to make life better in the region. He gave land and money for town buildings, parks, a theater, and a hotel. He also helped start a wood products factory.

Hops made many farmers rich, including Meeker. At one point, he said he earned half a million dollars from his crops. In 1880, he wrote his first book, Hop Culture in the United States. Soon after, he became known as the "Hop King of the World." By the 1880s, he was the richest man in the territory. He even had a hop business branch in London. He represented Washington Territory at an exposition in New Orleans in 1885–1886. He also took exhibits to a fair in London. In 1886, Meeker tried to become the territory's representative in Congress, but he lost. He supported women's right to vote. This was a big political fight in Washington Territory that lasted many years.

Eliza Jane felt the family should live in a nicer house than their old cabin. Between 1887 and 1890, she built what is now called the Meeker Mansion in Puyallup. It cost $26,000, which was a huge amount of money then. An Italian artist lived with the Meekers for a year, painting beautiful details on the ceilings. The Meekers moved in during 1890. That same year, Puyallup officially became a town. They gave their old homesite to the town for a park. In 1890, Meeker was the first mayor of Puyallup. He was elected mayor again in 1892.

Financial Troubles and the Klondike Gold Rush

In 1891, a disease caused by tiny bugs called hop aphids hit the hop farms. It spread from British Columbia to California. People tried spraying liquids to kill the bugs, but these sprays also hurt the hops. In 1892, the hop crop was only half of what it used to be. Meeker had given money to many farmers, and they couldn't pay him back. The problems in the valley got worse because of the Panic of 1893. This was a very bad worldwide economic downturn. Many businesses Meeker had invested in failed, like the Puyallup Electric Light Company. He had spent too much money and lost most of his fortune. Eventually, he lost his lands because he couldn't pay his debts.

Meeker spent part of the winter of 1895–1896 in London. He tried to get back what he could from his businesses there. In 1896, gold was found in Alaska and Canada. When Meeker returned from the United Kingdom, his sons, Marion and Fred, were getting ready to go to Alaska. They found that all the good gold claims were already taken. Still, the Meeker family thought finding gold could help them get their money back. They started a company to buy and sell mining claims, even though they didn't know much about mining.

In 1897, Meeker and his sons went to the Kootenay region of British Columbia, where gold had been found. Even though Meeker was 66 years old, he did his full share of the hard work. Both Meeker sons claimed land in Canada. But the mines needed more money to operate. Meeker tried to raise money in New York by talking to his old contacts. He got promises but not much cash. By July 1897, he was back in the Kootenays, working the claim. When gold was found in the Klondike that year, Meeker thought it was a better chance. He sent his son Fred to check it out. Fred returned with a report in November. The Meekers tried to get money for a mining trip to the Klondike, but they couldn't get enough from investors.

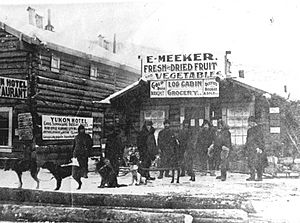

Even though he couldn't raise money for mining, Meeker was sure he could make money from the gold rush. He and Eliza Jane spent much of the winter of 1897–1898 drying vegetables. Ezra Meeker left for Skagway, Alaska, on March 20, 1898. He had 30,000 pounds of dried food. Fred Meeker and his wife Clara were already across the border in what would become the Yukon Territory. The 67-year-old Meeker, with a business partner, climbed the steep Chilkoot Pass. With thousands of others in boats, he floated down the Yukon River after the ice melted in late May. He sold all his vegetables in Dawson City in two weeks. He returned to Puyallup in July. But he set out again with more supplies the next month. This time, he and his son-in-law, Roderick McDonald, opened a store called the Log Cabin Grocery in Dawson City. They stayed there through the winter.

Meeker returned to the Yukon two more times, in 1899 and 1900. Most of the money he earned from groceries was invested in gold mining, and it was lost. When he left the Klondike for the last time in April 1901, he left behind his son Fred. Fred had died of pneumonia in Dawson City on January 30, 1901. In his writings, Meeker said he left the Yukon because of mining losses and his upcoming 50th wedding anniversary. Some historians think he left because people who had lost money in his businesses were trying to take the Meeker Mansion. Eliza Jane Meeker sold the mansion to their daughter Caroline and son-in-law Eben Osborne for $10,000 in mid-1901. Later that year, Ezra and Eliza Jane signed papers saying the house was her separate property. The sale allowed Ezra and Eliza Jane to live in the house for life and receive $50 per month. Ezra Meeker did not live there after his wife died in 1909. The Osbornes sold the house in 1915.

Promoting the Oregon Trail

Planning the 1906 Trip

After the Klondike trips, Meeker lived in Puyallup. He wrote books and was president of the Washington State Historical Society. He had helped start this group in 1891.

Meeker had thought for a long time about marking the Oregon Trail with stone monuments. He had traveled the Trail in 1852. By the early 1900s, he was worried that the Trail was being forgotten. Farmers were plowing over parts of it. As towns grew, the Trail disappeared under streets and buildings. Meeker felt it was urgent to save it. He wanted the Trail properly marked, and monuments built to honor those who died.

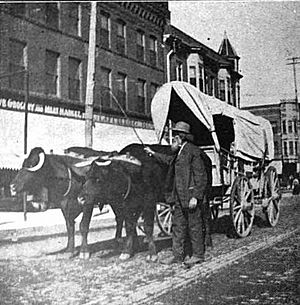

Meeker came up with a plan. He would travel the Trail again in an ox-drawn wagon. He hoped this would make people care about his cause. He believed that public interest would bring enough money to build markers and support him on his journey. Many people traveled by wagon selling fake medicines. But Meeker felt he would stand out. He was a real pioneer who could tell true stories of the Trail. He thought newspapers would write a lot about his travels.

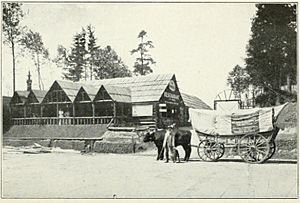

Meeker didn't have much money. So, he got help from friends. Ox-drawn wagons were not common in Puyallup in 1906. Meeker couldn't find a complete old wagon. He ended up using metal parts from three different old wagons. The wagon was built by Cline & McCoy in Puyallup. Meeker found a pair of oxen. One wasn't good, but the owner made him buy both. The one Meeker kept was named Twist. He found another ox, a very heavy one, from Montana. He named him Dave. Dave was difficult at first, but he eventually helped pull the wagon over 8,000 miles.

Meeker didn't have a dog on his 1852 trip. But he knew people liked dogs. So, he wanted to add one to his team. Jim was a big, friendly collie. He belonged to one of Meeker's neighbors. Meeker was impressed by how Jim slowly moved the neighbor's chickens away from the berry patch. He bought Jim for five dollars from one of the neighbor's children. Some of Meeker's friends tried to talk him out of the trip. One minister said it was "cruel" to let an old man start such a journey. He worried Meeker would die from the cold in the mountains.

Meeker had taken an ox team and wagon to an exhibition in Portland in 1905. On that trip, he looked for places to put monuments on the Cowlitz Trail. This was a trail pioneers used to go from the Columbia River to Puget Sound. He made plans with people in towns along that trail to raise money for monuments. He gave lectures to raise money, but he didn't get much. He took his team and wagon on short practice trips. Some people who remembered him as the "Hop King" made fun of him. After several days practicing camping on his lawn, Meeker left Olympia on February 19, 1906.

Traveling the Trail Again (1906–1908)

The first stop for "The Old Oregon Trail Monument Expedition" was Tenino, Washington. Meeker went ahead by train on February 20, 1906, to prepare for the first monument. He still didn't have a driver. So, his wagon was pulled to Tenino by horses, with the oxen walking behind. He asked a local stone quarry for a suitable stone. It was carved and dedicated in Tenino at a ceremony on February 21. He had less success as he traveled south towards Portland. No monuments were built at the other stops in Washington. Meeker placed wooden posts where monuments should go, but most towns didn't follow through.

People in Portland were also not very excited about Meeker's mission. Church leaders voted against letting Meeker use their building for a fundraising lecture. They said they wouldn't "encourage that old man to go out on the Plains to die."

In Portland, Meeker lost his remaining helpers. One refused a pay cut, and others left for personal reasons. One helper stayed for the boat trip up the Columbia River. He left at The Dalles. There, Meeker hired a driver and cook named William Mardon for $30 a month. Mardon stayed with Meeker for the next three years. Meeker also put a device to measure distance on his wagon. He called The Dalles "Mile Zero" of his trip. In The Dalles, Meeker started a pattern for his journey. He showed himself, his wagon, and his animals to the public. He sold tickets for his lectures about the Oregon Trail. He showed pictures using a special projector. He also met with town groups to raise money for a local monument. Often, these monuments were built after Meeker left. He would place a post to show where it should go.

A reporter named James Aldredge wrote in 1975 that Meeker, in his 70s, "must have been blessed with remarkable health and endurance." He added that Meeker himself was impressive, with his long white hair and beard. Another reporter, Bart Ripp, wrote in 1993 that Meeker's first trip in 1906 was supposed to be a speaking tour. But people were more interested in seeing "the old coot in a covered wagon." It was the 20th century, and Americans wanted a show.

As he traveled east from The Dalles, Meeker found more excitement than in his home state. He slowly passed through Oregon and Idaho. As word spread, sometimes towns were ready for him. They might have already ordered a stone or even had one ready. The monument in Boise, dedicated by Meeker on April 30, 1906, stands on the grounds of the Idaho State Capitol. On the road, he camped just like he had 50 years before. But in towns, he usually stayed in a hotel. Near Pacific Springs, at South Pass in Wyoming, Meeker had a stone carved. It marked where the Trail crosses the Continental Divide.

Nebraska was not very interested in Meeker's ideas. Near Brady, his ox Twist died. Meeker had to ask supporters back home for money. He hired horses to pull the wagon for a while. He tried using two cows, but it didn't work well. He was able to temporarily pair Dave with a more suitable cow. At the Omaha Stockyards, Meeker found another ox. He named him Dandy. He trained Dandy on the way to Indianapolis, near where Meeker used to live. This was 2,600 miles by road from Puyallup.

Starting in Nebraska, Meeker began selling postcards with photos from his trip. Postcards were very popular in the United States then. He also arranged to print a book about his 1852 journey. He wrote much of it during his lunch breaks on the 1906 trip. The money from selling these items helped him pay for his journey. Newspapers on the West Coast closely followed Meeker's adventures. When they heard of any disrespect towards Meeker, angry articles were printed.

After visiting Eddyville, Iowa, where he started in 1852, Meeker spent several weeks in Indianapolis. He left on March 1, 1907, when his permit to sell things on the streets expired. The Oregon Trail part of his trip was done. He continued east through Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York State. He wanted to raise public awareness and earn some money by selling his items. He often stayed several days in one place if sales of postcards and books were good.

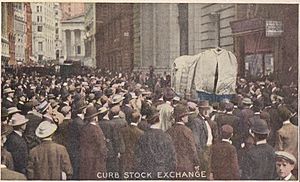

When the expedition reached New York City, the mayor was away. But the acting mayor told Meeker he couldn't give him a permit. However, he would tell the police not to bother him. This message didn't seem to get through. At 161st Street and Amsterdam Avenue, a policeman arrested Meeker's helper, Mardon. He was arrested for driving cattle on the streets of New York, which was against a local rule. Meeker refused to move his oxen, and the police didn't know how to move them. The problem was solved when higher officials ordered Mardon's release. Meeker wanted to drive down Broadway. It took a month to fix the legal issues. It took him six hours to drive the length of Manhattan. He had arranged for photographers from the press. They took pictures of him at the New York Stock Exchange and the sub-Treasury building on Wall Street. Later, he drove across the Brooklyn Bridge.

After a small family reunion near Elizabeth, New Jersey, Meeker headed south to Washington, D.C. He had hoped to meet President Theodore Roosevelt at his summer home. But Roosevelt's staff said no, offering a meeting in Washington instead. Members of Washington State's Congress helped arrange it. Meeker met Roosevelt on November 29, 1907. The President came outside the White House to see Meeker's wagon and team. He supported Meeker's work. He also supported Meeker's idea for a cross-country highway to honor the pioneers. (There were no such highways then.)

After Washington, the tour ended. Meeker went home to Puyallup by train to see his sick wife. When he returned to the East, he traveled by riverboat and train. He also had a wagon journey across Missouri. The expedition was unloaded from the train in Portland. Meeker then traveled north across Washington State. He received a much warmer welcome this time. He finished his journey in Seattle on July 18, 1908.

Working for the Oregon Trail (1909–1925)

Meeker ran a large pioneer exhibit and restaurant at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle. He later sadly said the Exposition cost him the money he earned from his book and card sales during his wagon tour. Later that year, he spent time in California, traveling with his wagon and team. Eliza Jane Meeker died in 1909 in Seattle. She had been sick for some years. Ezra Meeker was in San Francisco selling his goods when his wife died. It took three days to find him. Then he traveled north for the funeral before returning to his work. On New Year's Day 1910, Meeker and his wagon and team were in the Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena.

In 1910, a bill to give money for monuments to mark the Trail passed the House of Representatives. It was introduced in the Senate. It said no money would be spent unless the Secretary of War said no more money would be needed. Ezra Meeker started another two-year trip that year. This time, he focused on finding and marking where the Trail had been. Sometimes, the ruts (grooves) in the ground from the emigrants' wagons still existed. Other times, he had to ask old settlers where the Trail was. He traveled to Texas, but he couldn't get people interested in his project there. His tour ended in 1912 in Denver when a flood damaged his books. Still, Meeker's two trips led to 150 monuments being placed. A version of the bill passed the Senate in 1913, but it didn't pass the House. Even though this bill failed, groups started marking western trails. The Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution put up plaques along the Cowlitz Trail in 1916.

Starting in 1913, Meeker began planning his part in the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. He had given his wagon and oxen to a park in Tacoma. But when officials worried about the cost of building a proper display for them, Meeker took them back. He set off with them to California. Meeker decided Dandy was too old for the road. He had him killed in Portland in June 1914 and sent his hide back to Tacoma to be preserved. In November, the same happened to Dave in California. Meeker's wagon was shown at the Exposition in San Francisco. His stories of the Oregon Trail became one of the most popular attractions. However, he argued with the people running the Washington State Building. He felt it should be open on Sundays, when the most people came. When he returned, the preserved oxen and wagon were displayed at the Washington State History Museum. They were moved in 1995 and are now too fragile to display.

In 1916, 85-year-old Meeker made another trip. This time, he traveled by Pathfinder automobile. The Pathfinder Company lent Meeker a car with a covered-wagon-style top and a driver. This was a way to get publicity. Meeker also received a small payment. He traveled in the car from Washington, D.C., to Olympia. Meeker saw using a car as a way to promote the need for a highway across the country. During this trip, he gave talks about needing a national highway. Before he left, he met with President Woodrow Wilson and talked about it.

A man named Bernard Sun, whose grandparents were Oregon Trail pioneers, remembered another side of Meeker:

He would camp down on Rush Creek with a covered wagon. The old bum was riding a grub line. He would get meals from all the ranchers around here. My grandmother hated the sight of him. He would comb that long hair at the dinner table. Put his [false] teeth in to eat and take them out to talk.

World War I took public attention away from Meeker. But he used that time to plan for the future. On December 29, 1919, his 89th birthday, he started a new book. It was called Seventy Years of Progress in Washington. It received good reviews. With Dr. Howard R. Driggs, a professor, he published a new version of his memories. It was called Ox-Team Days on the Oregon Trail. In 1922, he got sick, which was rare for him. Newspapers reported that he refused to stay in bed. His grandson, who was a doctor, said he would put Meeker back to bed and keep him there "if I can."

After recovering, Meeker, who was in his 90s, started making new travel plans. The International Air Races were in Dayton, Ohio, in 1924. Meeker tried to get the War Department to let him fly there. He succeeded! He flew with an Army pilot, Oakley G. Kelly. At a stop in Boise, Meeker joked that they were going faster than his ox team. In Dayton, he met aviation pioneer Orville Wright. Meeker told him, "You'd be surprised at the difference between riding in a Prairie Schooner and in an airplane." The publicity was so good that the Army had Kelly fly Meeker the rest of the way to Washington, D.C. There, the former pioneer met President Calvin Coolidge in October 1924. Meeker returned to Seattle by train. He wanted the government to build a road over Naches Pass. He had guided his father's group through that pass 70 years before. Meeker ran for the Washington House of Representatives in 1924 but lost. In 1925, Meeker drove an ox team for several months while touring in J.C. Miller's Wild West Show.

The End of the Trail (1925–1928)

By 1925, Congress still hadn't given money to mark the Trail. One way to raise money from the government was to get Congress to approve a special coin. This coin was usually a half dollar. A group would buy the coins from the government at their face value. Then they would sell them to the public for more money. Meeker got this idea from a group in Idaho. They wanted a coin to help save Fort Hall. He arranged for their efforts to combine.

Starting in 1925, Meeker pushed for such a half dollar coin. It would honor the pioneers and provide money for his work. In April 1926, he spoke to a Senate committee. He urged them to pass the law. Congress agreed, and President Coolidge signed the bill on May 17, 1926. Meeker was there at the ceremony.

Meeker had started the Old Oregon Trail Association in 1922. In early 1926, it became the Oregon Trail Memorial Association (OTMA) in New York. It was given office space by the National Highways Association. The law for the new coin said the OTMA could buy Oregon Trail Memorial half dollars from the government. The coin was designed by Laura Gardin Fraser and her husband, James Earle Fraser. He designed the Buffalo nickel. Six million coins were approved. The first 48,000 were made for the Association at the Philadelphia Mint. When those ran low, 100,000 more were made at the San Francisco Mint. Meeker was less successful with the later coins, and many were not sold. Even though the Bureau of the Mint made more in 1928, these were held until after Meeker died. Tens of thousands of the earlier coins were also unsold.

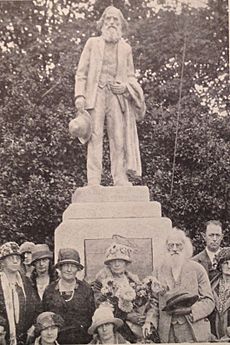

Seattle had been Meeker's home since he moved out of the mansion. But in the mid-1920s, the people of Puyallup wanted to honor him. They planned to put up a statue in Pioneer Park. This was the site of Meeker's old home. They also wanted to save the home site. Eliza Jane Meeker had planted ivy there 50 years before. They built a pergola (a garden structure) to support the plant. With the statue and pergola finished, Meeker returned to Puyallup for the dedication ceremony in 1926. That same year, at age 95, Meeker published his first and only novel. It was called Kate Mulhall, a Romance of the Oregon Trail.

Meeker was again speaking out for better roads. He got the support of Henry Ford. Ford built him a Model A car with a covered wagon-style top. It was called the Oxmobile. It was to be used in another trip over the Trail to promote Meeker's highway ideas. In October 1928, Meeker was in the hospital with pneumonia in Detroit. He returned to Seattle, where he got sick again. Meeker was taken to a room in the Frye Hotel. He told his daughter Ella Meeker Templeton, "I can't go. I have not yet finished my work." Ezra Meeker died there on December 3, 1928. This was just under a month before his 98th birthday. His body was taken in a procession back to Puyallup. He was buried next to his wife Eliza Jane in Woodbine Cemetery. Their gravestone was put up by the OTMA in 1939. It has a plaque based on the Oregon Trail Memorial coin that Ezra Meeker inspired. It reads, "They came this way to win and hold the West."

Ezra Meeker's Legacy

Dr. Howard R. Driggs took over as president of the OTMA after Meeker died. He stayed in that role until he died in 1963. The year 1930 marked 100 years since Meeker's birth. It was also 100 years since the first wagon train left St. Louis for the Oregon Country. This year was called the Covered Wagon Centennial. The biggest event was at Independence Rock in Wyoming, a famous landmark on the Oregon Trail. This event included dedicating a plaque of Meeker, placed in the rock. For many years, the OTMA dedicated monuments along the Oregon Trail every summer. Even though the OTMA no longer exists, state historical groups continue this work.

The special half dollar coins were made in small numbers in most years of the 1930s. After coin collectors complained about the long series and high prices, Congress stopped further minting in 1939. The first road across America, the Lincoln Highway, was finished in the 1920s. Others soon followed. Meeker's idea for a highway along the Trail wasn't built. But U.S. 30 generally follows the route of the Oregon Trail.

Several places related to Meeker are still in Puyallup. Besides his grave, there is the Meeker Mansion. It is now owned and being restored by the Ezra Meeker Historical Society. There is also Pioneer Park, where the ivy-covered pergola and the statue of Meeker can be found.

Historian Lori Price said, "Throughout his long life of nearly 98 years, the word for Meeker was action." Historian David Dary says Meeker was mainly responsible for making people interested in the Oregon Trail again. According to Bert Webber, "There would be no 'Oregon Trail' to enjoy today if Ezra Meeker had not set out, by himself, and without government subsidy, to preserve it."

Books by Ezra Meeker

- Washington Territory West of the Cascade Mountains (1870)

- Hop Culture in the United States (1880)

- Pioneer Reminiscences of Puget Sound, the Tragedy of Leschi (1905)

- Ox Team; or, The Old Oregon Trail, 1852–1906 (1907)

- Ventures and Adventures of Ezra Meeker (1908)

- Personal Experiences on the Oregon Trail Sixty Years Ago (1912)

- Uncle Ezra's Pioneer Short Stories for Children (c. 1915)

- The Busy Life of Eighty-Five Years of Ezra Meeker (1916)

- Seventy Years of Progress in Washington (1921)

- Ox-Team Days on the Oregon Trail (1922)

- Kate Mulhall, a Romance of the Oregon Trail (1926)

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |