California Trail facts for kids

| California Trails |

|---|

| California Trail Map (NPS) |

| National Trail Map |

| Oregon Trail Map (NPS) |

| Pony Express Map (BLM) |

| Oregon-California Trail Map (OCTA) |

| Proposed Oregon, California, Mormon, Pony Express Trail Map (NPS) |

| U.S. River Maps (USGS) |

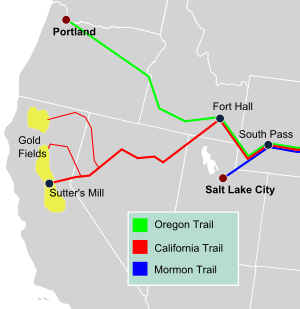

The California Trail was a very long path, about 1,600 miles (2,600 km) across the western part of North America. It stretched from towns along the Missouri River to what is now the state of California. This trail was used by many people, called emigrants, who wanted to move west.

The first part of the California Trail followed the same paths as the Oregon Trail and the Mormon Trail. These paths went along river valleys like the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater rivers in Wyoming. The trail had many different routes and shortcuts, adding up to over 5,000 miles (8,000 km) in total.

Contents

- Journey to California

- How the Trail Began (1811–1840)

- Preparing for the Journey

- Main Routes

- Trail Statistics

- Legacy of the Trail

- See also

Journey to California

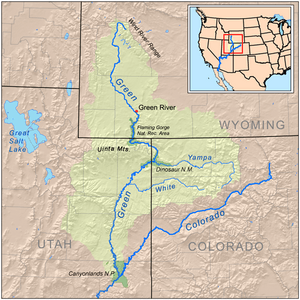

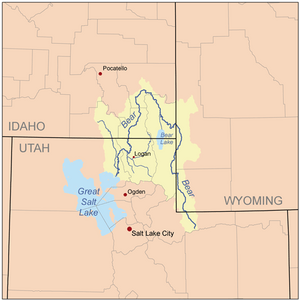

By 1847, two old fur trading forts became important starting points for different routes to Northern California. One was Fort Bridger in Wyoming, where the Mormon Trail turned southwest towards Salt Lake City. From Salt Lake, the Salt Lake Cutoff went north and west, rejoining the California Trail in the City of Rocks National Reserve in Idaho.

The main Oregon and California Trails crossed the Green River and then went over hills to the Bear River. Near Soda Springs, Idaho, both trails turned northwest to Fort Hall on the Snake River. From Fort Hall, the trails went southwest along the Snake River Valley for about 50 miles (80 km). Here, the California Trail split off, following the Raft River to the City of Rocks. Both the Salt Lake and Fort Hall routes were about the same length, around 190 miles (300 km).

From the City of Rocks, the trail entered Utah and then Nevada, following small streams until it reached the Humboldt River. The Humboldt River Valley was a key part of the journey. It provided water, grass, and wood, which were essential for travelers and their animals. However, the water became more salty, and there were very few trees. Travelers often found this part of the journey difficult.

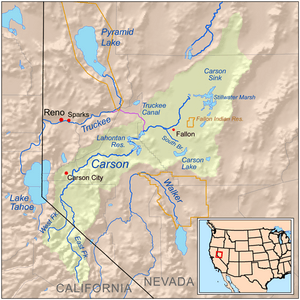

At the end of the Humboldt River, where it disappeared into the Humboldt Sink, travelers faced a tough challenge: the Forty Mile Desert. This was a very dry stretch before they could reach the Truckee River or Carson River in the Sierra Nevada mountains. These mountains were the last major obstacle before reaching Northern California.

In 1859, a shorter route called the Central Overland Route was developed. This route was about 280 miles (450 km) shorter and saved more than 10 days of travel. It went south of the Great Salt Lake and across central Utah and Nevada, using a series of springs. This route was later used by the Pony Express and the First transcontinental telegraph.

Once in western Nevada and eastern California, pioneers found several ways to cross the rugged Carson Range and Sierra Nevada mountains. These paths led to the gold fields and settlements of Northern California. The main routes were the Truckee Trail to the Sacramento Valley and, after 1849, the Carson Trail to the American River and the gold digging area around Placerville, California.

After 1859, the Johnson Cutoff and the Henness Pass Route across the Sierra were greatly improved. These became toll roads, meaning travelers paid a fee to use them. This money helped maintain the roads. These roads were also used to carry supplies from California to Nevada, especially for miners working at the Comstock Lode. The Johnson Cutoff was even used by the Pony Express year-round.

The California Trail was heavily used from 1845 until after the American Civil War. In 1869, the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed. This made cross-country travel much quicker and easier, taking about seven days by train. As a result, trail traffic dropped very quickly.

About 2,700 settlers used the trail from 1846 to 1849. These settlers helped California become a U.S. possession. After gold was discovered in January 1848, word spread about the California Gold Rush. From late 1848 to 1869, over 250,000 people, including businessmen, farmers, pioneers, and miners, traveled the California Trail. The number of new settlers was so high that by 1850, California had enough residents (120,000) to become the 31st state.

The original trail had many branches, totaling about 5,500 miles (8,900 km). About 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of the old wagon ruts still exist in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, and California. These are historical reminders of the huge migration westward. Parts of the trail are now protected by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the National Park Service (NPS) as the California National Historic Trail.

How the Trail Began (1811–1840)

The California and Oregon Trails started as paths used by mountain men and fur traders between 1811 and 1840. At first, you could only travel them on foot or horseback. South Pass (Wyoming), an easy way to cross the U.S. continental divide, was found in 1812 by Robert Stuart. In 1824, fur traders Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick rediscovered South Pass and the river valleys leading to the Missouri River.

After 1824, U.S. fur traders developed trails that could be used by wagons. These trails followed the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater rivers to the Green River. Here, fur trading companies often held their yearly Rocky Mountain Rendezvous. This was a lively event where trappers, Native Americans, and travelers traded furs and restocked supplies.

Early Explorers

Parts of the California Trail were discovered by American fur traders like Kit Carson, Joseph R. Walker, and Jedediah Smith. They explored much of the West. British traders from the Hudson's Bay Company also explored the Humboldt River from 1830 to 1840, but their findings were not widely known. The Humboldt River was important because it offered a natural path across Nevada to California, providing water and grass.

In 1832, Captain Benjamin Bonneville used the fur traders' paths to take 20 wagons over South Pass to the Green River. This was the first time wagons crossed South Pass.

In 1833, Captain Bonneville sent Joseph R. Walker to explore the Great Salt Lake desert and find a route to California. Walker rediscovered the Humboldt River in Nevada. After crossing the dry Forty Mile Desert, they went through the Carson River Canyon and over the Sierra Nevada mountains. They reached the Central Valley of California and continued to Monterey. Walker's return route crossed the southern Sierra mountains through what is now called Walker Pass.

The Humboldt River Valley was crucial for the California Trail. It provided water and grass for livestock and emigrants. The trail connected the Snake River to the Humboldt River using the Raft River, Junction Creek, and Thousand Springs Creek.

By 1836, a rough wagon trail existed to Fort Hall, Idaho. In July 1836, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding were the first white pioneer women to cross South Pass on their way to Oregon. They left their wagons at Fort Hall and continued by pack train.

Around 1837, John Marsh (pioneer), the first American doctor in California, wanted to encourage Americans to move to California. He wrote many letters describing California's climate and soil, and the best route to follow (the California Trail). His letters were widely read and helped start the first major immigration to California. The trail ended at his ranch, and he welcomed immigrants there.

First Wagons to California

The first group to use part of the California Trail to reach California was the Bartleson–Bidwell Party in 1841. They left Missouri with 69 people. Near Soda Springs, Idaho, about half the group decided to go to Oregon, while the other half tried to reach California. Without guides or maps, they followed the Bear River, which led them to the Great Salt Lake. They then traveled west across the desert north of the Great Salt Lake.

They missed the start of the Humboldt River and had to leave their wagons in Nevada. They continued west using their oxen and mules as pack animals. They eventually found the Humboldt River and followed it to its end. After crossing the difficult Forty Mile Desert, they turned south and followed the Walker River to the Sierra Nevada mountains. They crossed the Sierra, eating many of their oxen for food, but everyone survived.

Joseph Chiles, a member of the 1841 party, returned east in 1842. In 1843, he led his own company back to California. He hired Joseph R. Walker as a guide. Walker led the wagons along the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall, then turned west towards the Humboldt River. They blazed a wagon trail down the Humboldt River Valley and across the Forty Mile Desert to the Carson River. They then turned south, traveling east of the Sierra, and eventually abandoned their wagons near Owens Lake. They crossed the Sierra via Walker Pass by pack train.

In 1843–1844, U.S. Army Colonel John C. Frémont and his scout Kit Carson explored the Humboldt River. They crossed the Forty Mile Desert and followed the Carson River over the Carson Range and Sierra Nevada in February 1843. They reached Sutter's Fort near Sacramento, California. Fremont used the information from his explorations to create the first good map of California and Oregon in 1848.

The first group to cross the Sierra with their wagons was the Stephens–Townsend–Murphy Party in 1844. They followed the Humboldt River across Nevada and the Truckee Trail Route across the Forty Mile Desert and along the Truckee River to the Sierra. They crossed the Sierra at Donner Pass by unloading their wagons and pulling the parts up steep slopes with oxen. Some wagons were left at Donner Lake. They were caught by early winter snows and had to hike out, but their wagons were retrieved in the spring of 1845. This established a rough wagon route over the Sierra.

Hastings Cutoff

In 1846, Lansford Hastings led a party on the Hastings Cutoff, which left the California Trail at Fort Bridger. This route went through the rugged Weber River canyon and then south of the Great Salt Lake, across about 80 miles (130 km) of waterless Bonneville Salt Flats. The Hastings Cutoff rejoined the California Trail near Elko, Nevada. Hastings's party was just two weeks ahead of the Donner Party.

The Donner Party also took a branch of the Hastings trail across the Wasatch Range. This rough trail slowed them down by about two weeks. The Mormon Trail later followed a similar path but built a much better trail in 1847. All of the Hastings Cutoffs were very hard on wagons, livestock, and travelers. They were longer, harder, and slower than the regular trail, so they were mostly abandoned after 1846.

Salt Lake Cutoff

In 1848, the Salt Lake Cutoff was discovered. This allowed travelers to use the Mormon Trail from Fort Bridger to Salt Lake City. In Salt Lake, they could get repairs, fresh supplies, and livestock. The trail from Fort Bridger to Salt Lake City and over the Salt Lake Cutoff was about 180 miles (290 km) before rejoining the California Trail near the City of Rocks. This cutoff had good water and grass, and many thousands of travelers used it.

Central Overland Route

In 1859, Captain James H. Simpson of the U.S. Army surveyed what became the Central Overland Route. This route went from central Utah to Genoa, Nevada, through central Nevada. It was about 280 miles (450 km) shorter than the Humboldt River route and saved over ten days. This route was used by settlers, the Pony Express, stagecoach lines, and the First transcontinental telegraph after 1859.

Preparing for the Journey

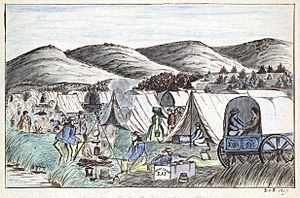

Before starting, travelers often sold their farms or businesses to buy supplies. Most people going to California in 1849 were men. About half of the gold seekers went by sea, and half went overland. Those going overland usually lived in the Midwest and traveled by steamboat to their starting point on the Missouri River.

Most travelers were farmers and already owned a wagon and livestock. A typical setup for three to six people included one or two small farm wagons with canvas covers, six to ten oxen, and chains and yokes. Wagons were light, about 1,300 pounds (590 kg) empty, and could carry about 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg) of supplies. They were pulled by 4 to 6 oxen, mules, or horses. More animals were usually brought along in case some got lost or died.

Oxen were popular because they were cheaper, tougher, stronger, and easier to train. They could also survive on the sparse feed found along the way. Most people walked alongside their wagons. Mules were the second choice, but trained mules were hard to find. Horses often struggled with the long journey and poor feed.

Food for the trip had to be compact and nonperishable. Many brought dried fruit and vegetables to prevent scurvy. Recommended food per adult for the four- to six-month trip included 150 pounds (68 kg) of flour, 50 pounds (23 kg) of bacon, and smaller amounts of sugar, coffee, and dried fruit. Some families brought milk cows, goats, and chickens for fresh milk and eggs.

Cooking was done over a campfire, using wood, dried buffalo dung, or sagebrush as fuel. Simple cooking tools like Dutch ovens, pots, and pans were used. Meals often included bacon, beans, coffee, and biscuits.

Most travelers slept on the ground, only using the wagon in bad weather. Water buckets and canteens were essential. One of the first tasks at each stop was to find water and gather fuel for a fire.

Each man usually carried a rifle or shotgun for hunting and protection. Farm tools like shovels, picks, and axes were also brought to clear paths or repair wagons. Awls, needles, and thread were used for repairs. Travelers also brought books, Bibles, and diaries.

Non-essential items were often left behind to lighten the load, especially before difficult sections of the trail. Many discarded items were salvaged by others. For example, Mormons sent groups to collect iron and other supplies from abandoned wagons.

Main Routes

The Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails often followed the same paths until they split in Wyoming, Utah, or Idaho. The exact route to California depended on the starting point, the final destination, and the time of year. There was no government control over the routes. Travelers relied on each other, trading posts, and a few Army forts.

To find water and grass, the trails usually followed river valleys. Wood for fires came from trees, brush, or dried buffalo dung. Wagons could travel over very rough terrain, including steep mountains and streams. Early travelers had to find or make paths through difficult areas. Later travelers used the improvements made by those before them. Most trips started in April or May, when grass was growing and trails were dry, and aimed to finish by September or October before winter snows.

Feeder routes crossed Missouri and Iowa to the Missouri River. Early starting points included Independence, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas. Later, Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha, Nebraska, became popular. Many emigrants from the East Coast traveled by steamboat down the Ohio River to St. Louis, then up the Missouri River to their departure point.

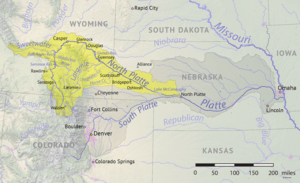

Those starting in Kansas often followed the Santa Fe Trail route, then crossed the Kansas and Wakarusa rivers. They then followed the Little Blue River or Republican River into Nebraska. Those starting in Iowa or Nebraska followed the north side of the Platte River. The eastern end of the trail was like a frayed rope, with many paths joining near Fort Kearny in Nebraska.

Dangers on the Trail

Preferred camping spots along the Platte River often became sources of cholera infections, especially during the cholera pandemic of 1849-1855. Cholera caused severe vomiting and diarrhea, and could spread easily through contaminated water. Thousands died from cholera along the trail, often buried in unmarked graves in Kansas and Nebraska. At the time, people didn't know about germs, so they didn't understand how cholera spread.

The Great Platte River Road

The Platte River in Nebraska and Wyoming was too shallow and muddy for boats, but its valley provided an easy path for wagons. It sloped gently upward as it went west, offering water, grass, and buffalo for food. There were trails on both sides of the river. The Platte's water was silty, but it could be used if no other water was available.

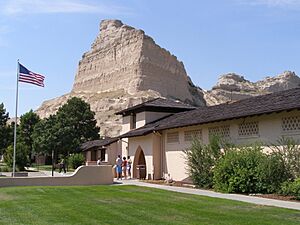

Travelers south of the Platte crossed the South Platte River, often by ferry, before continuing up the North Platte River to Fort Laramie. Along this route, they saw famous landmarks like Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff. After Fort Laramie, the road became much rougher. The Platte and North Platte rivers were followed for about 650 miles (1,050 km) to Casper, Wyoming.

Sweetwater River

Southwest of Casper, the North Platte River meets the Sweetwater River (Wyoming). The trail crossed the North Platte by ferry or bridge. From here, settlers entered a difficult section called Rock Avenue, which led to the Sweetwater River. Later settlers used a route through Emigrant Gap to reach Rock Avenue, bypassing Red Buttes.

Along the Sweetwater valley, travelers reached Independence Rock (Wyoming). This rock was named by Jedediah Smith in 1824 on July 4th. Emigrants tried to reach it by July 4th to ensure they would arrive in California or Oregon before winter snows. Many carved or painted their names on the rock. Other landmarks included Split Rock and Devil's Gate (Wyoming).

The trail crossed the Sweetwater River nine times. Before the sixth crossing, travelers found Ice Slough, a welcome treat of ice that lasted until early summer. The trail then crossed a large hill called Rocky Ridge, a major obstacle. After Rocky Ridge, the trail descended to the ninth and final crossing of the Sweetwater at Burnt Ranch.

In 1853, the Seminoe Cutoff was established. It bypassed Rocky Ridge and four river crossings, which was helpful during high water. This route was used often in the 1850s, especially by Mormon groups.

Immediately after crossing the Sweetwater at Burnt Ranch, the trail crossed the continental divide at South Pass (Wyoming). This was a major milestone, meaning settlers had truly entered the Oregon Territory. Nearby Pacific Springs offered the first water after leaving the Sweetwater River.

From South Pass to the Humboldt River

After South Pass, the main trail went to the Green River. After crossing the Green River by ferry, the trail continued to Fort Bridger. Here, travelers could take the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City or go to Fort Hall. The main trail to Fort Hall went north from Fort Bridger to the Bear River Valley. The trail along the Bear River usually had good grass, water, and wood. They followed the Bear River to Soda Springs, Idaho.

About 5 miles (8 km) west of Soda Springs, "Hudspeth's Cutoff" (1849) went west, bypassing Fort Hall. It had five mountain ranges to cross but took about the same time as the main route. Its main benefit was spreading out traffic in busy years.

The first California Trail pioneers, the Bartleson–Bidwell Party, followed the Bear River southwest from Soda Springs, not knowing it led to the Great Salt Lake. They then struggled across the desert north of the Great Salt Lake, eventually abandoning their wagons in eastern Nevada. This very difficult route was rarely used again.

West of Fort Hall, the trail went southwest along the Snake River. At the junction of the Raft River and Snake River, the trail split from the Oregon Trail. It followed the Raft River southwest to the City of Rocks National Reserve. Hudspeth's Cutoff and the Salt Lake Cutoff both rejoined the California Trail near the City of Rocks. The trail then continued west over Granite Pass, entering the Great Basin. It followed Goose Creek and Thousand Springs Valley to the Humboldt River near Wells, Nevada. This 160-mile (260 km) section provided enough water and feed for emigrants.

Cutoffs to the Humboldt River

The Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff (1844) saved about 50 miles (80 km) from the main route through Fort Bridger. It left the main trail near South Pass and went west across about 45 miles (72 km) of desert before reaching the Green River. This cutoff saved distance but often resulted in dead oxen and wrecked wagons due to the harsh desert.

The Green River was wide, deep, and powerful. Several ferries were set up to cross it. After crossing the Green River, many took the Slate Creek Cutoff, which avoided most of the waterless desert of the Sublette Cutoff.

Salt Lake Cutoff

After 1848, travelers needing repairs or supplies could stay on the Mormon Trail for about 120 miles (190 km) from Fort Bridger to Salt Lake City. Salt Lake City was the only major settlement along the route. From there, they could return to the California Trail using the Salt Lake Cutoff, which went northwest around the Great Salt Lake, rejoining the main trail at the City of Rocks. This route was about 20 miles (32 km) shorter than going via Fort Hall.

Central Overland Route

In 1859, the Central Overland Route was developed. This route bypassed both Fort Hall and the Humboldt River trails. It was discovered by U.S. Army Captain James H. Simpson. This route was about 280 miles (450 km) shorter and over ten days quicker. It followed the Mormon Trail from South Pass to Salt Lake City, then went south of the Great Salt Lake across central Utah and Nevada. This route was used by wagon trains, the Pony Express, stagecoach lines, and the First transcontinental telegraph after 1859.

Across the Great Basin on the Humboldt River

The Humboldt River flows over 300 miles (480 km) westward across the Great Basin in Nevada, eventually evaporating into the Humboldt Sink. The Great Basin has no outlet to the sea. The Humboldt River provided a natural path with water and feed. However, its water quality worsened further west, and wood for fires was scarce, consisting mostly of sagebrush and willows.

The trail from the Snake River to the Humboldt River passed through the City of Rocks. The trail then continued west over Granite Pass, which had a steep descent. The trail then went through Thousand Springs Valley, eventually reaching the Humboldt River near Wells, Nevada.

The trail followed the Humboldt west for about 65 miles (105 km) to Carlin Canyon (Nevada). This narrow canyon required many river crossings and could be impassable during high water. The Greenhorn Cutoff was developed to bypass it. West of Carlin Canyon, the trail climbed through Emigrant Pass and rejoined the Humboldt at Gravelly Ford. Here, the river had a gravel bottom and was easy to cross. Many travelers rested here. The trail then split, following both the north and south banks of the river, rejoining at Humboldt Bar.

At the Humboldt Sink, the Humboldt River disappeared into a marshy, salty lake. Near here was one of the worst sections of the California Trail: the Forty Mile Desert.

The Truckee River and the Carson River flow eastward from the Sierra Nevada into the Great Basin, about 40 miles (64 km) from the end of the Humboldt. All California Trail emigrants had to cross the Forty Mile Desert to reach either river. Before crossing, the main trail split into the Truckee River Route (1844) and the Carson Trail (1848).

The Forty Mile Desert was a barren, waterless, salty wasteland. It was one of the most feared sections of the trail because emigrants were often weak, tired, and low on supplies. They usually crossed it at night to avoid the intense heat. The ground was littered with abandoned goods, wagons, and dead animals. Many animals and people died on this crossing. In 1850, a count showed over 1,000 dead mules, 5,000 dead horses, 3,750 dead cattle, and 953 emigrant graves in the Forty Mile Desert.

Crossing the Sierra Nevada

The high, rugged Carson Range and Sierra Nevada mountains were the final obstacles. The Sierra Nevada is a large block of granite that slopes gradually west but rises steeply on its eastern side. Today, only about nine roads cross the Sierra, and half may be closed in winter.

Truckee Trail

The Truckee Trail (1844) crossed the Forty Mile Desert. After reaching the Truckee River near Wadsworth, Nevada, emigrants were relieved by its cool water, fresh grass, and shade. They often rested for a few days. The Truckee Trail followed the Truckee River past Reno, Nevada, to the Truckee River Canyon near the Nevada-California border. This canyon was steep and rocky, requiring many crossings of the cold river.

In 1845, Caleb Greenwood developed a new route that bypassed the difficult Truckee River Canyon. This route, though longer, avoided many river crossings and became the main Truckee Trail. The trail passed north of Lake Tahoe and followed Donner Creek to Donner Lake, then ascended to Donner Pass.

Crossing Donner Pass often required disassembling wagons and hoisting them up cliffs with oxen. From Donner Summit, the trail descended the South Fork of the Yuba River. The first resting spot was Summit Valley. The trail down the western slope was very rocky and steep, passing through Emigrant Gap (California). This difficult route, ending far from the main gold regions, was little used after 1849 when the Carson Trail became popular.

Later, the Truckee Trail was improved for freight wagons and emigrants. In 1863, the Central Pacific Railroad spent over $300,000 improving a new toll road, the Dutch Flat Donner Lake Toll Wagon Road, along the Truckee route. This road was used to haul freight to Nevada and supply railroad workers. Today, Interstate 80 roughly follows the original Truckee Trail.

Carson Trail

The widely used Carson Trail (1848), also called the Mormon Emigrant Trail, crossed the Forty Mile Desert from the Humboldt Sink to the Carson River near Fallon, Nevada. The desert crossing was very hard due to loose sand and poisonous water. It was often littered with discarded supplies, dead animals, and graves.

The Carson Trail was first developed by about 45 members of the Mormon Battalion in 1848. They were driving wagons and livestock east to Salt Lake City. They followed Iron Mountain Ridge to Tragedy Spring, where they found three of their scouts murdered. From there, the Mormon group ascended to West Pass and then dropped to Caples Lake. They went through Carson Pass, elevation 8,574 feet (2,613 m).

To cross the Carson Range, the trail followed the Carson River through a very rough canyon filled with boulders. The Mormons used fire and cold water to break up rocks and widen the canyon. By 1853, this road became a toll road and was improved.

Travelers heading west in 1848 and later followed the trail blazed by the Mormons. After crossing the Forty Mile Desert, they went up the Carson River valley. The road through Carson River Canyon was very rough, but it led to beautiful Hope Valley. From Hope Valley, travelers climbed a steep, rocky path called "The Devil's Ladder" to reach Carson Pass. This section was very difficult but could be done in about one day. The trail crossed the Sierra Crest through Carson Pass.

At that time, the trail was blocked by the Carson Spur. The Carson Trail had to turn south at Caples Lake and ascend West Pass to cross the Sierra Crest. This path was easier than the climb to Carson Pass and was used by thousands of wagons. The Carson Trail was a direct route to Placerville and the gold country.

One drawback of the Carson Trail was its high elevation, often over 8,000 feet (2,400 m), where snow covered it for much of the year. The Johnson Cutoff became the preferred trail because it was lower and improved.

Today, California State Route 88 follows much of the original Carson Trail.

Johnson Cutoff

The Johnson Cutoff (1850–51), also called the Placerville Route, went from Carson City, Nevada, to Placerville. It crossed the Carson Range by following Cold Creek and Spooner Summit. Near Lake Tahoe, it climbed steep ridges and then made a steep ascent over Echo Summit (Johnson's Pass). The descent from Johnson's Pass led to Slippery Ford on the South Fork American River. From there, it followed the river to Placerville. This route became a major competitor as the main route over the Sierra. It could be kept at least partly open in winter.

In 1855, California tried to fund a wagon road over the Sierra, but it was ruled unconstitutional. Local counties then funded improvements to the Placerville route, which was called the Day Route. This was the first publicly financed road improvement over the Sierra. The Pony Express used this route in 1860–61. After 1860, the road was greatly improved as a toll road to the mines in Virginia City, Nevada. Today, U.S. Route 50 in California roughly follows this route.

Henness Pass Road

The Henness Pass Road (1850) was an 80-mile (130 km) trail over the Sierra from Verdi, Nevada, to Camptonville, California. It was developed as a wagon toll route by Patrick Henness. The route went from Dog Valley (near Verdi) to Webber Lake, over 6,920-foot (2,110 m) Henness Pass, and into Camptonville. After 1860, extensions went south to Carson City and the Comstock Lode. This road became one of the busiest trans-Sierra trails, favored by teamsters and stage drivers for its lower elevations and easier grades. It had many camps and relay stations. The route was mostly abandoned after the railroads were completed in 1869. Today, it is a gravel U.S. Forest Service road.

Beckwourth Trail

The Beckwourth Trail (1850) left the Truckee River Route at Truckee Meadows (now Sparks, Nevada). It went north and crossed the Sierra at 5,221-foot (1,591 m) Beckwourth Pass. After the pass, the trail went west through Plumas, Butte, and Yuba counties, ending at Marysville, California. Today, California State Route 70 generally follows this path.

Other Sierra Roads

- Nevada City Road (1850): A 25-mile (40 km) cutoff from the Truckee Trail to Nevada City, California. California State Route 20 follows it today.

- Auburn Emigrant Road (1852): From the Truckee trail to Auburn, California, for new gold diggings. California State Route 49 approximates this path.

- Luther Pass Trail (1854): Connected the Carson River Canyon road with the Johnson Cutoff. California State Route 89 follows it today.

- Daggett Pass (1850): A 10-mile (16 km) toll road across the Carson Range, used to get to Virginia City, Nevada. Nevada State Route 207 approximates this road.

- Grizzly Flat Road (1852): An extension of the Carson trail to the gold diggings at Grizzly Flat.

- Volcano Road (1852): From the Carson Trail to Volcano, California.

- Big Tree Road & Ebbetts Pass Road (1851–1862): From Murphys and Stockton to mining towns near Markleeville, California. It approximates California State Route 4 over 8,730-foot (2,660 m) Ebbetts Pass. This route was little used by emigrants.

- Sonora Road (1852): From the Carson Trail to Sonora, California. It crossed the Forty Mile Desert to the Carson River, then went south to the Walker River, following it to the Sierra. It made a very steep ascent to 9,625-foot (2,934 m) Sonora Pass. This was the highest road across the Sierra. California State Route 108 roughly follows this route. It was little used after 1854.

Applegate–Lassen Cutoff

The Applegate–Lassen Cutoff (1846–48) left the California Trail near the Rye Patch Reservoir on the Humboldt River in Nevada. It went northwest, bypassing the worst of the Sierra Nevada, through Rabbithole Springs, the Black Rock Desert, and High Rock Canyon. After about 100 miles (160 km) of desert travel, it reached Surprise Valley and climbed steeply to 6,300-foot (1,900 m) Fandango Pass. From there, it descended to Fandango Valley on the shores of Goose Lake.

The Applegate Trail branch went northwest into Oregon. The California branch, the Lassen Cutoff (1848), went southwest through the Devil's Garden along the Pit River, passing east of Lassen Peak. It eventually swung west to Lassen's rancho near the Sacramento River, then followed the river south to Sutter's Fort and the gold fields. This road was very rough.

The Applegate–Lassen Cutoff was about 150 miles (240 km) longer than other routes, adding 15 to 30 days of travel. It avoided the Forty Mile Desert and high passes but had difficult desert crossings with limited grass and water. Many travelers took it by mistake, finding that earlier travelers had stripped the land bare. In 1849, about 7,000 to 8,000 people took this longer trail, losing many animals and suffering greatly. By 1853, faster routes were developed, and traffic on this cutoff declined.

Nobles Road

In 1851, William Nobles surveyed a shorter version of the Applegate–Lassen trail. This route, called Noble's Road, left the main trail near Lassen's meadow (Rye Patch Reservoir) and went west to Shasta, California. It bypassed most of the long Applegate-Lassen loop. It depended on springs for water. Today, Nevada State Route 49 and California State Route 44 approximate this route.

California Toll Roads over the Sierra

The discovery of the rich Comstock Lode in Nevada in 1859 led to major improvements on Sierra roads. Good roads were needed to transport miners, workers, and supplies. Tolls paid for these improvements. The mines required millions of dollars of investment and thousands of tons of supplies, food, and firewood.

Starting in 1860, many emigrant trails were improved into toll roads and bridges by private companies. The two main toll roads were the Henness Pass Route and the Placerville Route (Johnson's Cutoff). The Placerville route was shorter and had the advantage of connecting to the Sacramento Valley Railroad. These roads had major improvements, costing thousands of dollars, and employed many workers.

During summer, the roads were often packed with heavily loaded wagons. Mail and passenger stages usually traveled at night to avoid slower wagon traffic. Stagecoaches could make the trip from Placerville to Virginia City in about 18 hours. These toll roads generated significant income.

Competition arrived in July 1864 when the Central Pacific Railroad opened the Dutch Flat and Donner Lake Wagon Road. This route followed much of the original Truckee Trail but was greatly improved by the railroad's large workforce. This new toll road helped the railroad earn money while it was being built. It slowly took over much of the shipping to Virginia City. Today's Interstate 80 follows much of this route.

Tolls were charged on nearly all Sierra trail crossings. A typical toll from Sacramento to Virginia City was about $25–$30 for a freight wagon. These tolls paid for road improvements and maintenance.

Most heavy wagon freighting and stage use over the Sierra stopped after the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. The railroad made the trip faster, cheaper, and safer. The California Trail then reverted mostly to local traffic.

Trail Statistics

Immigrants

| Year | Oregon | California | Utah | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1834–39 | 20 | - | - | 20 |

| 1840 | 13 | - | - | 13 |

| 1841 | 24 | 34 | - | 58 |

| 1842 | 125 | - | - | 125 |

| 1843 | 875 | 38 | - | 913 |

| 1844 | 1,475 | 53 | - | 1,528 |

| 1845 | 2,500 | 260 | - | 2,760 |

| 1846 | 1,200 | 1,500 | - | 2,700 |

| 1847 | 4,000 | 450 | 2,200 | 6,650 |

| 1848 | 1,300 | 400 | 2,400 | 4,100 |

| Tot to '49 | 11,512 | 2,735 | 4,600 | 18,847 |

| 1849 | 450 | 25,000 | 1,500 | 26,950 |

| 1850 | 6,000 | 44,000 | 2,500 | 52,500 |

| 1851 | 3,600 | 1,100 | 1,500 | 6,200 |

| 1852 | 10,000 | 50,000 | 10,000 | 70,000 |

| 1853 | 7,500 | 20,000 | 8,000 | 35,500 |

| 1854 | 6,000 | 12,000 | 3,200 | 21,200 |

| 1855 | 500 | 1,500 | 4,700 | 6,700 |

| 1856 | 1,000 | 8,000 | 2,400 | 11,400 |

| 1857 | 1,500 | 4,000 | 1,300 | 6,800 |

| 1858 | 1,500 | 6,000 | 150 | 7,650 |

| 1859 | 2,000 | 17,000 | 1,400 | 20,400 |

| 1860 | 1,500 | 9,000 | 1,600 | 12,100 |

| Total | 53,000 | 200,300 | 43,000 | 296,300 |

| 1834–60 | Oregon | California | Utah | Total |

| 1861 | – | – | 3,148 | 5,000 |

| 1862 | – | – | 5,244 | 5,000 |

| 1863 | - | – | 4,760 | 10,000 |

| 1864 | - | – | 2,626 | 10,000 |

| 1865 | - | – | 690 | 20,000 |

| 1866 | - | – | 3,299 | 25,000 |

| 1867 | - | – | 700 | 25,000 |

| 1868 | - | – | 4,285 | 25,000 |

| Total | 80,000 | 250,000 | 70,000 | 400,000 |

| 1834–67 | Oregon | California | Utah | Total |

Records of emigrants for early years are not complete. However, emigration to California greatly increased due to the California Gold Rush in 1849. After gold was discovered, California remained the top destination for most emigrants until 1860, with almost 200,000 people traveling there between 1849 and 1860.

Travel after 1860 is less known because the American Civil War caused many disruptions. Many people on the trail from 1861–1863 were trying to escape the war.

While many people moved west, far more chose to stay home. Between 1840 and 1860, the U.S. population grew by 14 million, but only about 300,000 made the trip. Between 1860 and 1870, the U.S. population increased by seven million, with about 350,000 of this growth in Western states. Many were discouraged by the cost, effort, and dangers of the trip. It's estimated that 3–10% of immigrants died on the way west.

Costs

The cost of traveling the California or Oregon Trail varied. The cheapest way was to work as a wagon driver or herd animals, which could even earn a small profit. Farmers often already owned a wagon and livestock, so their trip cost about $50 per person for food and other items. Individuals buying everything needed could spend $150 to $300 per person.

As the trail became more developed, additional costs for ferries and toll roads were about $30 per wagon, or about $10 per person.

Deaths

| Cause | Estimated deaths |

|---|---|

| Cholera1 | 6,000–12,500 |

| Indian attacks2 | 3000–4500 |

| Freezing3 | 300–500 |

| Run overs4 | 200–500 |

| Drownings5 | 200–500 |

| Shootings6 | 200–500 |

| Scurvy7 | 300–500 |

| Accidents with Animals8 | 100–200 |

| Miscellaneous9 | 200–500 |

| Total Deaths | 9,700–21,000 |

| See Notes |

The journey west was difficult and dangerous, but the exact number of deaths is not known. Graves were often hidden to prevent animals or Native Americans from disturbing them. Diseases like cholera were the main cause of death, especially from 1849 to 1855, killing 6,000 to 12,000 people.

Attacks by Native Americans were probably the second leading cause of death, with about 500 to 1,000 people killed between 1841 and 1870. Other common causes included freezing to death (300–500), drowning in river crossings (200–500), being run over by wagons (200–500), and accidental gun deaths (200–500).

Many travelers suffered from scurvy by the end of their trips. Their diet of flour, dried corn, and salted pork lacked important nutrients. Scurvy is a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C and can be deadly if not treated. Some believe scurvy deaths might have been as high as cholera deaths.

Accidents with animals, such as kicks, falls, or stampedes, caused 100 to 200 or more deaths. Miscellaneous deaths included homicides, lightning strikes, childbirths, snake bites, flash floods, falling trees, and wagon wrecks, totaling 200 to 500 or more deaths.

According to historian John Unruh, about 4% of all travelers on the trails, or 16,000 out of 400,000 pioneers, may have died during the journey.

Legacy of the Trail

The California Trail, along with the Oregon Trail, played a huge role in expanding the United States to the West Coast. Without the thousands of American settlers in Oregon and California, this expansion might not have happened. Interestingly, both the Oregon and California Trails were established as known routes in 1841 by the same group of emigrants, the Bartleson–Bidwell Party.

Part of the trail's route across Nevada was later used for the Central Pacific Railroad, which was part of the First Transcontinental Railroad. In the 20th century, the trail's route was used for modern highways, like U.S. Route 40 and later Interstate 80. You can still see ruts from wagon wheels and names carved with axle grease on rocks in the City of Rocks National Reserve in southern Idaho, reminding us of this great migration.

|

See also

In Spanish: Ruta de California para niños

In Spanish: Ruta de California para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |