Jedediah Smith facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jedediah Smith

|

|

|---|---|

Jedediah Smith, life portrait, said to have been drawn by a friend, from memory, after the 1831 death of Smith

|

|

| Born |

Jedediah Strong Smith

January 6, 1799 |

| Died | May 27, 1831 (aged 32) Northern Mexico Territory, south of present-day Ulysses, Grant County, Kansas

|

| Cause of death | Attacked by Native Americans |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Diah, Old Jed, and Jed. |

| Occupation | clerk, frontiersman, hunter, trapper, author, cartographer, explorer |

| Employer | Ashley-Henry Fur Company, partner in the Ashley Smith Fur Company and Smith, Jackson and Sublette' |

| Known for | Being a mountain man and explorer of the Rocky Mountains, American West Coast, American Southwest, first west-east crossing of the Great Basin Desert and naming of Cache Valley, Utah |

| Parent(s) | Jedediah Smith, 1st and Sally Strong |

| Relatives | Austin Smith (brother) Ira Smith (brother) Peter Smith (brother) |

Jedediah Strong Smith (born January 6, 1799 – died May 27, 1831) was an American explorer and fur trapper. He was a brave frontiersman who explored much of the Rocky Mountains and the western parts of the United States in the early 1800s. He was also a mapmaker and writer.

After his death, people mostly forgot about Jedediah Smith for 75 years. But later, he became known as the American explorer whose journeys helped pioneers find the important South Pass. This pass was a key route for crossing the Continental Divide (the main mountain ridge that separates rivers flowing east from those flowing west) on the Oregon Trail.

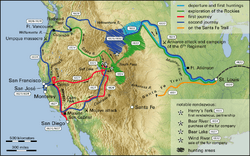

Smith came from a simple family. In 1822, he joined a fur trading company in St. Louis. He led the first recorded trip from the Great Salt Lake area to the Colorado River. His group was the first U.S. citizens to cross the Mojave Desert into what is now California, which was then part of Mexico. On their way back, Smith and his friends were also the first U.S. explorers to cross the Sierra Nevada mountains and the tough Great Basin Desert.

The next year, Smith's group was the first to travel north from California by land to reach the Oregon Country. Jedediah Smith survived three attacks by Native Americans and even a grizzly bear attack! His explorations and detailed travel notes were very helpful for later American westward expansion.

In March 1831, Smith asked the Secretary of War, John Eaton, for money to explore the West for the government. He also told Eaton he was finishing a map of the West based on his travels. In May, Smith and his business partners started a trading trip to Santa Fe. On May 27, while looking for water in what is now southwest Kansas, Smith disappeared. Weeks later, it was learned he had been killed by Comanche warriors. His body was never found.

After his death, Smith's achievements were largely forgotten. But in the early 1900s, historians began to study his life. Books written about him in 1936 and 1953 helped make him a national hero. Smith's 1831 map of the West was even used by the U.S. Army and explorer John C. Frémont in the 1840s.

Contents

- Early Life and Adventures

- Joining the Fur Trade

- Arikara Attack and Smith's Bravery

- First Big Expedition and a Grizzly Bear Attack

- Fur Trade Partnerships

- First Trip to California (1826–1827)

- Second Trip to California (1827–1828)

- Journey to the Oregon Country

- Blackfeet Expedition and Return to St. Louis

- Death of Jedediah Smith

- Smith's Legacy

- Who Was Jedediah Smith?

- How We Remember Him

- His Own Words

- Places Named After Him

- Honors and Memorials

- In Popular Culture

- See also

Early Life and Adventures

Jedediah Smith was born on January 6, 1799, in Jericho, New York. His father, Jedediah Smith I, owned a general store. His family had come to New England from England a long time ago.

Jedediah learned to read and write well. Around 1810, his family moved west to Erie County, Pennsylvania. When he was 13, Smith worked as a clerk on a ship on Lake Erie. This job taught him about business and made him want to explore the wilderness.

A family friend, Dr. Titus G. V. Simons, was a mentor to young Smith. It's believed that Simons gave Smith a copy of Meriwether Lewis' and William Clark's book about their famous 1804–1806 expedition to the Pacific Ocean. Legend says Smith carried this journal on all his travels. Smith later gave Clark, who was in charge of Indian affairs, a lot of information from his own trips. In 1817, Smith's family moved west again to Ohio.

Joining the Fur Trade

Jedediah Smith came from a modest family and wanted to make his own way. In 1822, he was in St. Louis. He answered an advertisement from General William H. Ashley. Ashley and Major Andrew Henry had started a fur trading company. They were looking for "One Hundred Enterprising Young Men" to explore and trap furs in the Rocky Mountains.

William Clark, who was in charge of Indian affairs, encouraged Ashley and Henry to compete with British fur traders. Smith, who was 23 years old and tall, impressed General Ashley and was hired. Smith started his journey up the Missouri River on a boat called the Enterprize. He soon saw the western frontier and met the Sioux and Arikara tribes.

Arikara Attack and Smith's Bravery

In the spring of 1823, Major Henry sent Smith to meet Ashley and buy horses from the Arikaras. The Arikaras were not friendly to white traders because of a recent fight. Ashley met Smith at the Arikara village. They traded for horses and buffalo robes and planned to leave quickly.

But bad weather delayed them. Before they could leave, an event caused the Arikaras to attack. Forty of Ashley's men, including Smith, were caught in a dangerous spot. Twelve men were killed in the battle. Smith showed great courage during the fight. People said he was always first to face danger and last to retreat.

Smith and another man walked back to Fort Henry to tell Major Henry about the defeat. Ashley and the others went downriver and got help from Colonel Henry Leavenworth. In August, Leavenworth led 250 soldiers, along with fur traders and Lakota Sioux warriors, to fight the Arikaras. After a difficult campaign, a peace treaty was made. Smith was made a commander of one of the groups of fur traders and was known as "Captain Smith" from then on.

First Big Expedition and a Grizzly Bear Attack

In the fall of 1823, Smith and about 10 to 16 men headed west into the Rocky Mountains. This was his first major expedition into the far West. Smith's group was the first Euro-Americans to explore the southern Black Hills in what is now South Dakota and eastern Wyoming.

While looking for the Crow tribe, Smith was attacked by a large grizzly bear. The bear tackled him, breaking his ribs. It ripped open his side with its claws and put his head in its mouth. When the bear left, Smith's men helped him. They cleaned his wounds and bandaged his broken ribs. After he recovered, Smith grew his hair long to cover the large scar from his eyebrow to his ear. The only known portrait of him, painted after his death, shows this long hair.

The group spent the winter of 1823 in the Wind River Basin. In 1824, Smith sent an expedition to find a good route through the Rocky Mountains. He got information from Crow natives. The Crows showed Smith and his men the way to the South Pass. Smith and his men crossed this pass from east to west. They found the Green River in what is now Wyoming.

The group split up to trap furs. They met again in July on the Sweetwater River. They decided that Thomas Fitzpatrick would take the furs and the news of the South Pass to Ashley in St. Louis. The South Pass had been discovered earlier by a Scottish-Canadian trapper named Robert Stuart in 1812. But this information was kept secret. Smith later wrote a letter in 1830 to the Secretary of War, John Eaton, making the location of the South Pass public. This was very important for future pioneers.

Fur Trade Partnerships

In July 1825, Ashley and Smith met at the first rendezvous. A rendezvous was a big meeting where fur trappers, traders, and Native Americans gathered to trade furs and supplies. Ashley offered Smith a partnership in his company.

At the second rendezvous in 1826, Ashley decided to leave the fur business. He sold his share to a new partnership: Smith, Jackson, and William Sublette. The new partners soon realized that beavers, whose furs they trapped, were becoming scarce in their usual areas. They looked at maps that showed rivers to the west that might have more beavers. They also hoped to find the legendary Buenaventura, which was thought to flow all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

First Trip to California (1826–1827)

Smith and 15 men left the Bear River on August 7, 1826. They headed south through present-day Utah and Nevada to the Colorado River. The journey was very difficult. They found shelter in a friendly Mojave village near what is now Needles, California. The men and horses rested there. Smith hired two guides to lead them west through the Mojave Desert.

They reached the San Bernardino Valley in California. Smith and a companion rode to the San Gabriel Mission on November 27, 1826. The mission director, Father José Bernardo Sánchez, welcomed them.

The next day, the rest of Smith's men arrived. The head of the mission's army took all their guns. On December 8, Smith was called to San Diego to meet Governor José María Echeandía. The governor was surprised and suspicious of the Americans entering California without permission. He arrested Smith, thinking he might be a spy.

Smith was held for about two weeks. He asked for permission to travel north to the Columbia River along the coast to return to U.S. territory. With help from an American sea captain, Smith was finally released. Governor Echeandía ordered Smith and his group to leave California the same way they came in. He told them not to travel up the coast. Smith was allowed to buy supplies for his return trip east.

Smith's group left the mission areas in mid-February 1827. Once outside the Mexican settlements, Smith decided he had followed the order to leave by the same route. He then turned north into the Central Valley. They trapped beavers along the Kings River.

By early May 1827, Smith and his men had traveled about 350 miles north. They were still looking for the Buenaventura River, but found no break in the Sierra Nevada mountains. They tried to cross the Sierra Nevada near Ebbetts Pass, but the snow was too deep.

Since they couldn't find a good path for their group to cross and faced unfriendly Native Americans, Smith made a decision. They didn't have time to travel north to the Columbia River and still make it to the 1827 rendezvous. So, they would go back to the Stanislaus River and set up camp. Smith would take two men and some extra horses to get to the rendezvous quickly. He would then return with more men later in the year, and the rest of the group would continue to the Columbia.

After a tough crossing of the Sierra Nevada, Smith and his two men traveled east across central Nevada. They crossed the Great Basin Desert during the hot summer. They and their horses struggled to find food and water. After two days without water, one man collapsed. Smith found water and brought it back to him. Finally, they saw the Great Salt Lake, which was a "joyful sight" for Smith. They reached the rendezvous on July 3. The mountain men celebrated Smith's arrival, as they had thought he was lost.

Second Trip to California (1827–1828)

After the rendezvous, Smith left to rejoin the men he had left in California. He was with 18 men and two French-Canadian women. They followed much of the same route as the year before. However, the Mojave people along the Colorado River, who had been friendly before, had fought with other trappers. They were now angry at white traders.

While crossing the river, Smith's group was attacked. Ten men, including Silas Gobel, were killed, and the two women were captured. Smith and the eight survivors fought back. They killed two Mojaves and wounded one, causing the rest to run off. Smith and his men then retreated on foot across the Mojave Desert to the San Bernardino Valley.

Smith and the other survivors were again welcomed at San Gabriel. They moved north to meet the group left in the San Joaquin Valley, reuniting on September 19, 1827. This time, the priests at Mission San José were not as welcoming. They had already heard that Smith was back in the area. Smith's group also visited settlements at Monterey and Yerba Buena (San Francisco).

Governor Echeandía, who was in Monterey, arrested Smith again, along with his men. But the governor released Smith again after some English-speaking residents spoke up for him. Smith had to pay a $30,000 bond. He promised to leave California immediately and not return. But as before, Smith and his group stayed in California, hunting in the Sacramento Valley for several months.

They reached the northern edge of the valley. They looked at the route to the northeast along the Pit River but decided it was too difficult. So, they turned northwest toward the Pacific coast to find the Columbia River and return to the Rocky Mountains. Jedediah Smith became the first explorer to reach the Oregon Country by land, traveling up the California coast.

Journey to the Oregon Country

When Smith's group left Mexican California and entered the Oregon Country, both Britain and the United States had rights to the land under the Treaty of 1818. Smith's group, which now had 19 men and over 250 horses, met the Umpqua people. The tribes along the coast had heard about conflicts between Smith's group and other Native Americans, so the Umpqua were cautious. One Umpqua person stole an ax. Smith's group treated some of the Umpqua harshly to get the ax back.

On July 14, 1828, while Smith and two others were scouting a trail north, his group was attacked in their camp on the Umpqua River. On August 8, 1828, Arthur Black, one of Smith's men, arrived at the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) post at Fort Vancouver. He was badly wounded and believed he was the only survivor.

Chief Factor John McLoughlin, who was in charge of Fort Vancouver, sent word to local tribes. He offered rewards if they brought Smith and his men to the fort safely. He also organized a search party. Smith and the two others, who had seen the attack from a hill, arrived at the fort two days after Black. Smith's group represented American interests in the fur trade.

McLoughlin sent Alexander McLeod south with Smith, Black, and others to find any other survivors and their goods. They found 11 bodies, which they buried. They confirmed that all 15 missing men had died. They also recovered 700 beaver skins and 39 horses.

When Smith returned to Fort Vancouver, he met with Governor Simpson of the HBC. Simpson paid Smith $2,600 for the horses and furs. In return, Smith promised that his American fur company would only operate east of the Great Divide. Smith stayed at Fort Vancouver until March 12, 1829, then traveled east to meet his partners.

Blackfeet Expedition and Return to St. Louis

In 1829, Captain Smith led a fur trade trip into Blackfeet territory. He managed to get a good amount of beaver furs before being driven back by the Blackfeet. Jim Bridger, another famous mountain man, helped on this profitable trip.

Over four years of fur trapping, Smith, Jackson, and Sublette made a lot of money. At the 1830 rendezvous on the Wind River, they sold their company to other trappers, who renamed it the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

After Smith returned to St. Louis in 1830, he and his partners wrote a letter to Secretary of War Eaton. They told him about the British possibly turning Native Americans against American trappers in the Pacific Northwest. Smith's letter was seen as a clear statement about American interests in the West. He also described Fort Vancouver and how the British were building a new fort, suggesting they wanted to settle the Oregon Country permanently.

Smith had not forgotten his family's financial struggles. After making a large profit from selling furs (over $17,000, which would be about $500,000 today), Smith sent $1,500 to his family in Ohio. His brother Ralph bought a farm with the money. Smith also bought a house in St. Louis to share with his brothers.

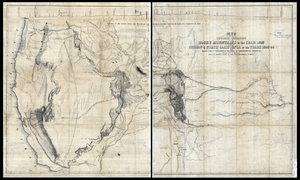

Smith and his partners also worked on a map of their discoveries in the West. Smith was the main contributor to this map. On March 2, 1831, Smith wrote another letter to Eaton. He mentioned the map and asked to lead a government-funded exploration, similar to the Lewis & Clark expedition.

Smith and his partners also prepared to join the supply trade to Santa Fe. They got a special travel document from Senator Thomas Hart Benton. They started a company of 74 men, twenty-two wagons, and a cannon for protection.

Death of Jedediah Smith

Since he didn't hear back from Secretary Eaton, Smith joined his partners and left St. Louis to trade in Santa Fe on April 10, 1831. Smith was leading the group on the Santa Fe Trail on May 27, 1831. He left the group to look for water near the Lower Spring on the Cimarron River in what is now southwest Kansas. He never returned.

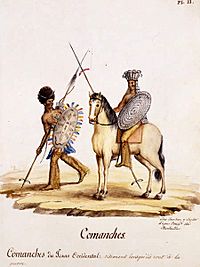

The rest of the group continued to Santa Fe, hoping Smith would meet them there, but he never did. They arrived in Santa Fe on July 4, 1831. Soon after, members of the group found a trader with some of Smith's personal items. It was learned that Smith had met with some traders just before approaching a group of Comanche warriors. Smith tried to talk with the Comanche, but they surrounded him, ready to attack.

Jedediah Smith was likely killed in what was then Northern Mexico Territory, south of present-day Ulysses, Kansas. According to his grand-nephew, there were 20 Comanches. Smith tried to make peace, but the Comanches scared his horse and shot him with an arrow. Smith fought back bravely, killing their chief. Another account says he killed two or three of their group before being overpowered. Smith's grand-nephew said that Smith fought so bravely that the Comanche thought he was more than human. They gave him the same funeral rites they gave their chief. Smith's brother, Austin, who was with the caravan, was able to get Smith's rifle and pistols back from the traders who had gotten them from the Comanche.

Smith's Legacy

After Smith's death, President Andrew Jackson launched a government-funded ocean exploration from 1838 to 1842. One goal was to explore the Pacific Northwest and claim the Oregon Country, which Smith had explored. The overland exploration of the West that Smith had asked for finally happened starting in 1842, led by Lieutenant John C. Frémont. Frémont's published explorations helped open the West for American expansion. Frémont became known as the "Pathfinder," while Smith's life was mostly forgotten for many years.

The shared control of the Oregon Country by Britain and the United States, where Smith stayed at Fort Vancouver, ended with the Oregon Treaty in 1846. In 1848, Mexico gave California, where Smith had been arrested twice, to the United States after the Mexican–American War.

Who Was Jedediah Smith?

Jedediah Smith was not a typical mountain man. He was known for being calm under pressure, very skilled at surviving in the wild, and a great leader. He was a practicing Christian, and his letters show his beliefs. While some stories say he always carried a Bible, there's no strong proof from his own writings or his companions. He was known for his strong moral code.

How We Remember Him

Smith was largely forgotten as a historical figure for over 75 years after his death. But in the early 1900s, people started to recognize his achievements. In 1918, a book by Harrison Clifford Dale helped bring his explorations to light.

Later, in the 1930s, Maurice S. Sullivan found parts of Smith's own travel writings. These writings gave a new, detailed look at Smith's explorations. In 1953, Dale Morgan's book, Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West, truly established Smith as an important American hero. His explorations were seen as just as important as the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

According to Maurice S. Sullivan, Smith was "the first white man to cross the future state of Nevada, the first to conquer the High Sierra of California, and the first to explore the entire Pacific Slope from Lower California to the banks of the Columbia River." He made many careful observations about nature and the land. His trips also showed that the legendary Buenaventura River probably didn't exist.

Jedediah Smith's explorations were key to making accurate maps of the Pacific West. He and his partners, Jackson and Sublette, created a map that was considered the best map of the Rocky Mountains and the country to the Pacific at the time. The original map is lost, but its information was added to an 1845 map by John C. Frémont.

His Own Words

Another important part of Jedediah Smith's story was found in 1967. More of his travel writings were discovered in an attic in St. Louis. This part described Smith's first California trip (1826–1827). These writings, along with a journal from his companion Harrison Rogers, were published in 1977.

Places Named After Him

Smith's explorations in California and Oregon led to two rivers being named for him: the Smith River (California) and Smith River (Oregon).

- Smith's Fork of the Bear River in Wyoming is named for him.

- The Jedediah Smith Wilderness in Wyoming also bears his name.

Honors and Memorials

Many places and groups honor Jedediah Smith:

- Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park and Campground

- Jedediah Smith Memorial Trail

- Dodge City Trail of Fame, inductee

- Jedediah Strong Smith's Route 1823, historic monument in South Dakota

- California Outdoors Hall of Fame, 2006 inductee

- Jedediah Smith Muzzleloaders Gun Club

- Jedediah Smith Road, Temecula, California

- Hall of Great Westerners, 1964 inductee, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

- Jedediah Smith Classic 50 mile run, Elverta, California

- Jed Smith Ultra Classic marathon, Sacramento, California

- Jedediah Smith Memorial, San Dimas, California

- Jedediah Smith Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, Apple Valley, California

In Popular Culture

- Jedidiah Smith - Frontier Legend (documentary)

- Taming the Wild West: The Legend of Jedediah Smith (2005) Reenactment Documentary; Smith is played by Sean Galuszka.

See also

In Spanish: Jedediah Smith para niños

In Spanish: Jedediah Smith para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |