Stanislaus River facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stanislaus River |

|

|---|---|

Stanislaus River at the historic covered bridge in Knights Ferry

|

|

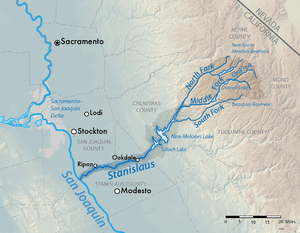

Map of the Stanislaus River watershed

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Counties | Alpine, Calaveras, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Tuolumne |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Middle Fork Stanislaus River–Kennedy Creek Near Leavitt Peak, Tuolumne County 9,635 ft (2,937 m) 38°14′21″N 119°36′43″W / 38.23917°N 119.61194°W |

| 2nd source | North Fork Stanislaus River Mosquito Lake, Alpine County 8,075 ft (2,461 m) 38°30′54″N 119°54′52″W / 38.51500°N 119.91444°W |

| River mouth | San Joaquin River Near Vernalis, San Joaquin 20 ft (6.1 m) 38°09′15″N 120°21′27″W / 38.15417°N 120.35750°W |

| Length | 95.9 mi (154.3 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 1,075 sq mi (2,780 km2) |

| Tributaries | |

The Stanislaus River is a river in north-central California, United States. It flows for about 96 miles (154 km) and is a branch of the San Joaquin River. The river starts as three different branches high up in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The Stanislaus River flows generally southwest through the farming area of the San Joaquin Valley. It joins the San Joaquin River south of Manteca. The river helps drain parts of five California counties. It is known for its fast-moving water and beautiful canyons in its upper parts. The river's water is used a lot for watering farms, making electricity, and providing drinking water.

Long ago, the Miwok people lived along the Stanislaus River. In the early 1800s, Spanish explorers came to the area. The river is named after Estanislao, a Native American leader. He led a rebellion in 1828 against the Mexican government, but was defeated on this river. During the California Gold Rush, many gold seekers came to the Stanislaus River. They often arrived through Sonora Pass, which is near the river's source. Many miners later settled along the lower Stanislaus River. Their farms and ranches are now part of a very rich farming area in the United States.

Early mining companies built canals and flumes to bring water from the Stanislaus River to gold mining sites. Later, farmers formed groups to control the river's water for irrigation. Starting in the early 1900s, many dams were built to store and move water. These dams often included systems to make hydroelectricity. In the 1970s, a large dam called New Melones Dam was built. This project faced strong opposition from people who enjoyed outdoor activities and environmental groups. They protested losing one of the last free-flowing parts of the Stanislaus River. Even though New Melones Dam was built, its completion is seen as the end of building large dams in the United States.

How water is used along the Stanislaus River is a debated topic. Farmers have older rights to use water, but there are also laws to protect endangered fish like salmon and steelhead trout. Farmers argue that giving water to fish harms the local economy, especially during dry years. Water managers try to find a balance between these different needs. These needs also include refilling underground water, controlling floods, and river activities like fishing and whitewater rafting.

Contents

Journey of the Stanislaus River

The Stanislaus River begins with three branches high in the Sierra Nevada mountains. These branches are in Alpine, Calaveras, and Tuolumne counties. The Middle Fork is the largest branch, about 46 miles (74 km) long. It starts in the Emigrant Wilderness area of the Stanislaus National Forest. It flows northwest and then west, passing through Donnell Lake and Beardsley Lake. These lakes are formed by dams that make hydroelectric power.

Below Beardsley Dam, the Middle Fork flows west to meet the North Fork at Camp Nine. Camp Nine is a popular spot for swimming and fishing. The North Fork is about 31 miles (50 km) long and starts in the Carson-Iceberg Wilderness. It flows southwest through several smaller dams that also make hydropower. Both forks flow through deep canyons in rough, heavily forested areas. The Stanislaus River is about 150 miles (240 km) long from its mouth to the very start of Kennedy Creek in the Emigrant Wilderness.

Where the Middle and North Forks meet is the official start of the Stanislaus River. It flows southwest through a canyon into the 12,500-acre (5,100 ha) New Melones Lake. This lake is in the Sierra Nevada foothills and forms the border between Calaveras and Tuolumne counties. The smaller South Fork joins the river at the reservoir. The South Fork flows for 42 miles (68 km) from the Sierra Nevada. Much of State Route 108 (the Sonora Pass Highway) runs next to the South Fork. It connects small towns in the upper Stanislaus area.

At the lower end of New Melones Lake is the 625-foot (191 m) tall New Melones Dam. This dam is the sixth tallest in the U.S. It was finished in 1979 to help control floods, provide water for farms, make electricity, and manage fish. Below New Melones, the river flows through the smaller Tulloch Reservoir. Then it reaches Goodwin Dam, which is the oldest dam on the river (built in 1913). Here, a lot of water is taken out for irrigation.

The Stanislaus River becomes much smaller after Goodwin Dam. It leaves the foothills and enters the farming area of Stanislaus County. This happens at the historic Gold Rush town of Knights Ferry. State Route 120 runs next to the river as it flows west into the Central Valley. It passes through Oakdale, the biggest town on the river. The river also flows along the northern edge of the Modesto area.

At Riverbank, the river starts to form the border between Stanislaus County and San Joaquin County. At Ripon, Highway 99 crosses the river. Below Ripon, the Stanislaus flows west-southwest through a low area called River Junction. It also passes Caswell Memorial State Park. Finally, it joins the San Joaquin River about 2 miles (3.2 km) northeast of Vernalis. This is about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Manteca.

River Flow and Water Levels

The Stanislaus River's natural flow, measured at New Melones Dam, is about 1,121,000 acre-feet (1.383 km3) each year. This is about 1,500 cubic feet per second (42 m3/s). About two-thirds of the river's water comes from melting snow between April and July. However, the highest water flows usually happen during winter rains. The amount of water in the river changes a lot from year to year. For example, in 1983, it had a high flow of 2,950,000 acre-feet (3.64 km3). In 1977, it had a very low flow of 155,000 acre-feet (0.191 km3).

The highest monthly flow is usually in May or June when snow melts the most. The lowest flow is typically in September or October, before autumn storms arrive. Since the late 1800s, the spring snowmelt has started two to six weeks earlier. This is because temperatures in the Sierra Nevada are getting warmer.

Taking water for farms and controlling it with dams has made the lower Stanislaus River flow less. It has also made the seasonal changes in water flow less extreme. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) measures the river's flow at Ripon. Before New Melones Dam was built (1941-1978), the average yearly flow was 1,008 cubic feet per second (28.5 m3/s). After the dam was built (1978-2013), the average yearly flow was 855 cubic feet per second (24.2 m3/s).

Stanislaus River Watershed

The Stanislaus River watershed covers 1,075 square miles (2,780 km2) of land. It has two main parts: the mountainous upper watershed and the lower watershed. Most of the river's water comes from the upper watershed. The lower watershed is narrower and has a lot of development. Goodwin Dam is usually seen as the line between these two parts.

The land in the watershed ranges from less than 15 feet (4.6 m) high at the San Joaquin River to over 10,000 feet (3,000 m) high in the Sierra Nevada. The amount of rain and snow changes from 20 inches (510 mm) in the valley to 50 inches (1,300 mm) or more at higher elevations. Above 5,000 feet (1,500 m), most of the precipitation falls as snow.

The upper watershed makes up 90 percent of the total area. It also provides most of the river's water. This area stretches from the foothills to the high alpine regions of the Sierra Nevada. It has rough, narrow canyons and ridges. The higher parts of the watershed are mostly federal Forest Service land and protected wilderness. The middle parts are a mix of state, federal, and private land.

The lower Stanislaus River watershed is only about one-tenth of the total area. It is mainly used for farming (61 percent) and city development (34 percent). Major towns near the lower river include Oakdale, Riverbank, and Ripon. The 60-mile (97 km) long lower river has been changed a lot. Water is taken out, and levees have been built to prevent floods. Much of the natural flood areas and riverside habitats are gone. The riverbed has also been dug up a lot for gravel mining.

River's History and Geology

The Stanislaus River likely formed about 23 million years ago. It flowed down from an ancient mountain range where the Sierra Nevada is now. Over time, huge lava flows filled the old canyon. About 9 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada mountains began to rise. This caused the Stanislaus River to carve new canyons through the rock. These lava flows are now known as the Stanislaus Formation. You can see them as the caprock on the "table mountains" around New Melones Lake.

As the mountains rose and erosion continued, the Stanislaus River carved the deep canyons we see today. It also helped create the flat floor of the Central Valley with its deposits of alluvium. Some of these river sediments contained placer gold. This gold was later discovered during the California Gold Rush. The lower part of the river is geologically young. It has continually cut new channels and filled in older ones.

Most of the shaping of the Stanislaus River basin happened during the Pleistocene Ice Ages, starting about 1 million years ago. During these ice ages, California had a much wetter climate. The average river flows might have been as high as today's flood levels. The climate was also cold enough for large glaciers in the Sierra Nevada. These glaciers carved large U-shaped valleys in the high elevations. They also provided huge amounts of meltwater, which sped up erosion in the river's canyons. During the last glacial period, the main Stanislaus glacier was up to 30 miles (48 km) long. Many features of the upper Stanislaus, like the Clark Fork valley, were shaped by ice.

History of the Stanislaus River

First People and Early Life

Humans first arrived in the Sierra Nevada area over 10,000 years ago. Near the Stanislaus River, archaeologists found the remains of a dwelling. This oval-shaped site, about 12 feet (3.7 m) wide, is estimated to be about 9,500 years old. It is the oldest known built home in North America. For centuries before Spanish explorers arrived, the Central Sierra Miwok people lived in the Stanislaus River basin.

The Miwok people mostly lived by hunter-gatherer methods. They also did some simple farming and used controlled fires to improve hunting grounds. The Miwok had their main villages in the lower foothills and the Central Valley. They spent winters there. In the summer, they traveled into the Sierra Nevada along the Stanislaus River. They gathered plant foods in the high mountains and escaped the summer heat.

Native Americans in the region lived in small groups called "tribelets." These groups had between 100 and 500 people. One group connected to the Stanislaus River was the "Walla" or "Wal-li." They lived in the hills between the Stanislaus and Tuolumne Rivers. The Stanislaus River's yearly floods created large areas of wetlands. These wetlands had many animals, birds, and fish. This supported a large Native American population.

European Explorers and the River's Name

The Spanish Empire claimed California in the 1770s. However, much of the Central Valley remained unexplored by the Spanish for decades. The first Spaniards to see the Stanislaus River were from Gabriel Moraga's expedition in 1806. They named the river Rio de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, meaning "River of Our Lady of Guadalupe". The river later became known as Río de los Laquisimes.

The Spanish did not build missions in the Central Valley. Instead, they forced thousands of Native Americans to work at missions along the coast. Mission San José was a common destination for Miwok people from the Laquisimes River area.

American explorers also visited the Laquisimes River area starting in the 1820s. They were looking for beaver and otter furs. Famous mountain men like Jedediah Smith explored the area. In 1827, Smith's group camped on the Laquisimes River near today's Oakdale. Smith called the river the "Appelamminy." He and two others later crossed the Sierra Nevada from this river. They were the first Europeans to do so.

Native Americans strongly resisted the Spanish mission system. Many escaped Native Americans fled to the Central Valley. Around November 1828, a Yokuts man named Estanislao led a revolt at Mission San Jose. He fled to the Laquisimes River area with many other natives. There, he gathered an army of different Native American groups. They raided missions and large ranches, stealing animals and freeing laborers.

The Mexican army, led by Mariano Vallejo, tried to stop the revolt. They were first defeated by the natives on the Laquisimes River. This battle is believed to have happened near today's Caswell Memorial State Park. Vallejo returned with more soldiers and cannon. He set fire to plants along the river banks to force the natives out. But Estanislao and his fighters escaped. They continued to raid Mexican settlements that winter. According to stories, Estanislao would carve an "S" into a tree after his attacks. This legend may have inspired the fictional character Zorro.

In June 1829, Vallejo finally defeated Estanislao on the Laquisimes River. Estanislao eventually returned to Mission San Jose. He was pardoned by the Mexican government. However, the Mexicans never again tried to control the eastern part of the San Joaquin Valley. The Laquisimes River was renamed the Stanislaus in Estanislao's honor.

European arrival also brought new diseases. In 1832, a fur trapping group may have accidentally brought malaria to the Central Valley. Over the next few years, malaria outbreaks killed thousands of Native Americans. They had no natural protection against these European diseases. A smallpox outbreak in 1837 killed even more people, including Estanislao.

Gold Rush and River Development

In the 1840s, many American settlers moved to the Central Valley of California. They wanted to claim the area's rich farmland. The first major American settlement on the Stanislaus River was founded in January 1847. About 30 Mormon colonists established "Stanislaus City." They built a sawmill and started growing wheat and vegetables. However, the settlement did not grow much and ended the next year. A huge flood in January 1848 was one reason for its decline.

California became part of the United States in 1848. In the same year, gold was found on the American River. This started the California Gold Rush. Gold was also found on the Stanislaus River in August 1848. Hundreds of miners quickly arrived. Many miners from the eastern United States came to California through Sonora Pass. This pass is near the source of the Middle Fork of the Stanislaus River. By 1849, about 10,000 miners had come to the Stanislaus River area.

The Stanislaus River was a very good place to find gold. In the early Gold Rush, it was known as the "Southern Mines." This was because it was the southernmost area where gold was being dug. At first, miners worked on their own small claims. But as the easy gold ran out, they worked together. They built large dam, ditch, and flume systems. These systems helped them wash gold out of the ground more efficiently. They also brought water to areas that didn't have it and provided water for farming. These were some of the first claims for water rights on the Stanislaus River.

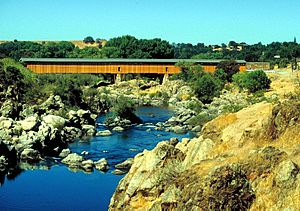

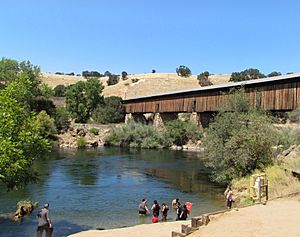

In 1849, William Knight started a ferry and trading post on the Stanislaus River. This served thousands of miners going to Sonora and other mining camps. Knight's Ferry became the main supply point for the region. It had daily stagecoach service to Stockton. After Knight's death, Lewis Dent took over the ferry. In 1854, a wooden covered bridge replaced the ferry. Knights Ferry also became home to a hotel, courthouse, flour mill, and jail. A huge flood in 1862 destroyed much of the town, including the bridge. But it was soon rebuilt. Knights Ferry was the county seat of Stanislaus County until 1872.

Mining companies built large water systems. For example, the Tuolumne County Water Company diverted water from the South Fork of the Stanislaus River. By 1853, it had 80 miles (130 km) of canals. These served up to 1,800 miners. Huge amounts of wood were needed to build these mining flumes and aqueducts. This led to a lot of trees being cut down in the lower Stanislaus area. These early waterworks were often poorly built and sometimes failed. In 1857, a dam on the South Fork collapsed. It flooded mining camps and killed sixteen people. Just a few years later, the 1862 flood destroyed most of the mining sites and buildings.

After the Gold Rush, fewer people visited the rough Stanislaus River area above the Sierra foothills. Knights Ferry became less important as many miners settled around Oakdale. The Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in Oakdale in 1872. This drew people to Oakdale instead of Knights Ferry. In 1895, Charles Tulloch bought water rights to an old mining ditch. He turned an old flour mill into the first hydroelectric plant on the Stanislaus River.

Development slowly moved higher into the Stanislaus watershed in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This was partly due to improvements to the Sonora Pass Highway. This road was a toll road from 1864 and was used a lot during the gold strike in Bodie in the 1870s. Today, most of the road has been replaced by the newer Highway 108.

Tourists started visiting the high country when cars became popular in the early 1900s. Many camps and resorts were built along the river. The Dardanelle Resort, built in 1923, operated until 2018. The new Dardanelle Bridge was built in 1933 to replace an older one. Both the resort and the bridge were destroyed in the 2018 Donnell Fire. There was also a lot of logging in the Stanislaus watershed foothills. Several small railroads went into the foothills to help with logging.

The upper Stanislaus watershed was also used for filming movies and TV shows. The Sierra Railway was a popular filming spot. In the 1930s, scenes for Robin Hood of El Dorado were filmed near the old Douglas Resort. In the 1970s, several episodes of the TV series Little House on the Prairie were filmed near Donnell Lake.

Stanislaus River Ecosystem

Plants and Animals of the River

The upper Stanislaus River watershed is mostly covered by forests. These forests have a mix of trees like ponderosa pine, white fir, Jeffrey pine, incense cedar, and sugar pine. Hardwood trees like California black oak and canyon live oak are common along streams and in canyons. In the foothills, you can find other hardwoods like chamise and manzanita.

Areas along the riverbanks, called riparian zones, are rare because the streambeds are narrow and rocky. These areas have trees like white alder and willow. Vernal pools, which are seasonal ponds, are found in flatter areas and also support riverside plants. The lower watershed, now mostly farmland, used to have grasslands, oak woodlands, and chaparral. The river's yearly floods once spread for miles, creating large wetlands. These wetlands had cottonwood, sycamore, and valley oak trees. However, much of this natural habitat has been lost due to development and gravel mining. Some large areas of riverside habitat still exist, like around Caswell Memorial State Park.

The California Department of Fish and Game has identified many animal species in the Stanislaus River watershed. These include up to 35 types of amphibians and reptiles, 57 mammal species, and over 200 bird species. Large mammals like mule deer, bighorn sheep, and black bear are common in the Stanislaus National Forest. The Stanislaus River is home to aquatic animals like beaver, river otter, and mink. These animals were hunted a lot for their fur in the 1800s.

At least 36 fish species live in the lower Stanislaus River. These include native fish like salmon, steelhead/rainbow trout, Pacific lamprey, hardhead, and Sacramento pikeminnow. There are also introduced fish like carp, sunfish, and bass.

Salmon and Steelhead Life Cycle

The Stanislaus River provides a home for native fish that travel between fresh water and the ocean. These are mainly Chinook (king) salmon and steelhead. These fish live most of their adult lives in the ocean. But they must return to fresh water in the river to lay their eggs (spawn). Naturally, the Stanislaus River had a large spawning run in late spring (April–June) and smaller runs in fall and winter.

When Goodwin Dam was built in 1913, it blocked fish from reaching about half of their spawning areas. Fish populations have gone down since then, especially after the Melones and Tri-Dam projects changed the river's flow. Between 1952 and 2015, the fall chinook population varied greatly. It was as high as 35,000 in 1953 and as low as zero in 1977. The average number of fall chinook in the 21st century has been 3,558 fish.

Historically, taking water for farms was seen as the main reason for fewer salmon and steelhead. Before New Melones Dam, the river often dried up in early summer. This happened because farmers used all the water, especially in dry years. This stopped young fish (smolt) from reaching the sea. The little water left was often too warm for fish to survive.

In 1992, federal dam operators started releasing large amounts of water into the Stanislaus River. These "pulse flows" happened during important spring and fall spawning seasons. They hoped to copy the natural conditions of snowmelt and autumn storms to help the fish reproduce. Between 2000 and 2009, about 55 percent of the Stanislaus River's natural flow was released from Goodwin Dam. This was much more than the historical average of 39 percent. In fall 2015, higher flows on the Stanislaus River led to over 11,000 chinook salmon returning to the river.

However, releasing water for fish competes with the need for water for farming. This program has not been popular with local farmers and water districts. Also, despite the pulse flows, salmon and steelhead numbers have continued to decline. Spring-run chinook salmon have disappeared from the Stanislaus watershed. Spring and fall steelhead runs are considered threatened. One big problem is that water temperatures must be below 55 °F (13 °C) for fish to spawn well. In dry years, releasing too much water for steelhead in the spring leaves less cold water for salmon and steelhead in the fall. Other factors like less riverside habitat, gravel mining, and introduced fish that eat native fish have also greatly affected native fish populations.

Balancing River Flow Needs

On April 8, 2015, after four years of severe drought, the Bureau of Reclamation started releasing water from New Melones for fish. Farmers protested this. Irrigation district managers tried to close the gates at Tulloch Dam to stop the water from flowing downstream. After a short disagreement, the Bureau of Reclamation stopped the flow. The districts objected because releasing water in the spring would greatly reduce their water supply. State rules require that a certain amount of water stay in New Melones for fall fish releases. Because of the drought, New Melones Lake was already low. There was not enough water for both farmers and the required spring and fall fish releases. Eventually, a temporary agreement was made. It allowed the lake to be drawn down to a lower level than environmental rules usually permit. This met the farmers' needs for the year but also led to warmer water temperatures.

It has been hard to measure how higher flows affect fish that travel between fresh water and the ocean. This is partly because of many other factors like pollution and non-native fish that eat them. A 2009 report suggested that even higher flows would be needed for fish populations to truly benefit. In 2017, a study found that the number of fish migrating out of the river might not be as closely related to artificial pulse flows as once thought. Data from 2005–2016 showed that fish migration reacted the same way to river flows of 700 cubic feet per second (20 m3/s) as they did to the required flows of 1,200 to 1,500 cubic feet per second (34 to 42 m3/s). The study also found that most fish migration happened during natural rainfall events in the lower river. It was not mainly due to artificial pulse flows from upstream dams.

The California Department of Water Resources still wants higher flows in the Stanislaus, Tuolumne, Merced, and San Joaquin Rivers. They focus on the amount of water released during spring snowmelt. While over half of the Stanislaus River's runoff flows freely down the river over the year, this amount is much lower (20 percent or less) during spring snowmelt. This is when most water is stored in reservoirs for later use. The state has suggested that 40 percent of the spring runoff should flow down the river. Some environmental groups want as much as 60 percent. These amounts would be more than what is already required. This would leave even less water to support the local farming economy.

The environmental program has also faced opposition from federal representatives. In 2015, a bill was introduced to Congress that would have allowed saving reservoir water during droughts. This water would not be released for environmental purposes. Because the Stanislaus River has limited flow, it is clear that not all demands on the river can be fully met. This forces water managers to find compromises. An temporary program started in 2016 allows Stanislaus irrigation districts to sell some river water to another water authority. This water must travel down the Stanislaus and San Joaquin Rivers. It can then be used to meet Stanislaus fish flow requirements, essentially doing two jobs at once. In 2016, this plan saved 75,000 acre-feet (93,000,000 m3) of water.

Fun on the Stanislaus River

Whitewater Adventures

The Stanislaus River was California's first popular river for whitewater rafting. In the 1970s, many companies offered rafting trips between Camp Nine and Parrott's Ferry Bridge. Although this part of the river was flooded by New Melones Lake in 1983, rafting and kayaking are still popular. People can raft on parts of the Middle Fork and North Fork, and on the main river below Goodwin Dam. The Camp Nine area can be rafted again when New Melones Lake is low.

The North Fork is the highest commercially rafted river in California. It is also considered one of the most challenging runs in the state. It has thirteen rapids that are Class IV or higher. The best times to raft are usually for six weeks in April and May. During the summer, water flows are controlled by New Spicer Meadow Reservoir. This reservoir usually releases water at night to make hydropower. The Forest Service suggests taking a guided trip because the river is very demanding. However, private trips are also allowed. The section from Goodwin to Knight's Ferry also has Class IV-V rapids. Below Knights Ferry, the Stanislaus River becomes wider and calmer. It has Class I-II rapids between there and Orange Blossom Park. Further downstream, many parts of the river are good for flat-water boating and swimming.

The Middle Fork has the most water flow. However, many hydropower projects take water from it. This often leaves the riverbed dry in summer. The Sand Bar and Mt. Knight runs are rated "difficult" (Class IV–V+). They depend on water releases from Sand Bar Dam. These releases only happen when the river flow is more than what the Stanislaus Powerhouse can handle. The average season for this run is only about 3 weeks long, usually in early June. The 8-mile (13 km) section between Donnells Dam and Beardsley Reservoir is known as "Hell's Half Acre." It flows through a narrow granite canyon with many very difficult drops. This section only runs when water is released from Donnells Dam. Because whitewater boating is becoming more popular, PG&E is thinking about releasing more water from the dam during the summer.

Parks and Public Places

About 520 square miles (1,300 km2) of the upper Stanislaus basin is inside the Stanislaus National Forest. This forest offers many outdoor activities. These include fishing, camping, backpacking, horseback riding, mountain biking, and snowmobiling. Highway 108 along the South/Middle Forks and Highway 4 along the North Fork provide access to the forest. Part of the Pacific Crest Trail also runs through the Stanislaus River watershed.

The upper Stanislaus also includes parts of two major wilderness areas. The 161,000-acre (65,000 ha) Carson-Iceberg Wilderness is along the North Fork and Clark Fork. The Emigrant Wilderness, covering 113,000 acres (46,000 ha), includes the upper Middle Fork. It also borders Yosemite National Park.

Boating, water-skiing, and camping are popular on the many reservoirs along the Stanislaus River. The largest, 12,500-acre (5,100 ha) New Melones Lake, is visited by up to 800,000 people each year. It has a full-service marina with boat rentals and supplies. The 2,000-acre (810 ha) New Spicer Meadow Reservoir and Beardsley Reservoir both have camping areas and boat ramps. These are managed by the Forest Service. Donnell Lake is also open to the public, but it is less crowded because it is harder to reach.

Along the lower Stanislaus River, most of the land is privately owned. However, there are sixteen public access points in the 60-mile (97 km) stretch between New Melones Dam and the San Joaquin River. The Knights Ferry Recreation Area has the historic Knights Ferry Covered Bridge. This is the longest such bridge in the western US. Other parks along the lower Stanislaus include Horseshoe, Orange Blossom, and Jacob Meyers Parks. The Oakdale and McHenry Recreation Areas also offer riverside trails, campgrounds, and access for boating and fishing. Caswell Memorial State Park covers 258 acres (104 ha) along the lower Stanislaus River. It is home to one of the last native oak woodlands along a river in the Central Valley.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |