New Melones Dam facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New Melones Dam |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | United States |

| Location | Near Jamestown, California |

| Coordinates | 37°56′50″N 120°31′41″W / 37.94722°N 120.52806°W |

| Construction began | 1966 |

| Opening date | 1979 |

| Owner(s) | U.S. Bureau of Reclamation |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Earth and rock embankment |

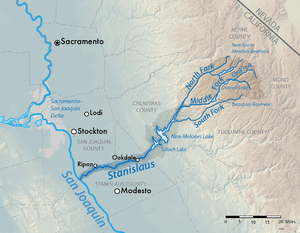

| Impounds | Stanislaus River |

| Height | 625 ft (191 m) |

| Length | 1,560 ft (480 m) |

| Spillway type | Ungated overflow |

| Spillway capacity | 112,600 cu ft/s (3,190 m3/s) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | New Melones Lake |

| Total capacity | 2,400,000 acre-feet (3,000,000 ML) |

| Catchment area | 904 sq mi (2,340 km2) |

| Surface area | 12,500 acres (5,100 ha) |

| Normal elevation | 1,088 ft (332 m) |

| Power station | |

| Commission date | 1979 |

| Hydraulic head | 480 ft (150 m) |

| Turbines | 2 × 150 MW Francis |

| Installed capacity | 300 MW |

| Annual generation | 417,880,000 KWh (2001-2015) |

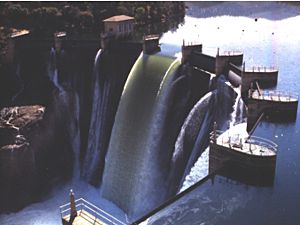

The New Melones Dam is a huge dam made of earth and rock. It is built on the Stanislaus River in California, USA. The dam is about 5 miles (8 km) west of Jamestown, California. It sits on the border of Calaveras and Tuolumne counties.

This impressive dam is 625 feet (191 meters) tall. It creates New Melones Lake, which is California's fourth largest reservoir. A reservoir is like a big artificial lake that stores water. New Melones Lake is located in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The dam helps in many ways. It supplies water for farming, generates electricity, controls floods, and offers fun recreation activities.

Building the New Melones Dam was approved in 1944. It was part of the Central Valley Project. This project helps bring water to farms in California's Central Valley. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the dam. Then, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation took over its operation.

Construction started in 1966. The new dam replaced an older, much smaller dam. The main part of the dam was finished in late 1978. New Melones Lake began filling up in 1978. The dam's power plant started making electricity in mid-1979.

The dam's construction led to a long environmental fight in the 1970s and 1980s. People protested because the dam would flood a beautiful part of the Stanislaus River. This area had exciting whitewater rapids. Protesters tried many ways to stop the lake from filling. But in 1983, huge floods filled the reservoir. The water almost went over the dam's emergency spillway.

The battle over New Melones Dam changed how people thought about rivers in California. It also influenced water rules for the whole country. Since this dam was built, no other dams of its size have been constructed in the United States.

Even today, the New Melones project causes some debate. The dam provides less water than expected. Also, some water is used to protect fish, which means less water for farms. The reservoir often doesn't have enough water to meet all the needs. Environmental groups want more water for fish. Farmers want more water for their crops.

Contents

How the Dam Works

The New Melones Dam and its lake are part of the Central Valley Project. The dam's main job is to control water from the Stanislaus River. This river's watershed covers about 904 square miles (2,341 km²). That's about 92% of the river's entire area.

The dam is 625 feet (191 meters) high from its base. It is 1,560 feet (475 meters) long. It contains about 15.7 million cubic yards (12 million m³) of material. This makes New Melones the second tallest earthfill dam in the U.S. It is also the sixth tallest dam overall.

When the lake is full, its surface is 1,088 feet (332 meters) above sea level. The lake covers 12,500 acres (5,059 ha) of land. It can hold 2.4 million acre-feet (3 km³) of water. An acre-foot is the amount of water needed to cover one acre of land with one foot of water.

About 450,000 acre-feet (0.56 km³) of the lake's capacity is saved for flood control. This means it can hold extra water during heavy rains. The dam helps keep the Stanislaus River from flooding. Between 1978 and 2010, the dam prevented about $505 million in flood damage. This included $231 million during the big flood of 1997.

Making Electricity

The dam has a power plant at its base. It uses the force of falling water to make electricity. The plant has two large turbines. Each turbine can make 150 MW of power. Together, they can produce 300 MW.

The plant makes electricity mostly when it's needed most, like during busy times of the day. The water released from New Melones Dam then flows into a smaller lake called Tulloch Dam. This helps keep the river flow steady.

From 2001 to 2015, the power plant made about 418 million kilowatt-hours (KWh) of electricity each year. In 2006, it made a lot of power, 910 million KWh. But in 2015, it made less, only 130 million KWh. This plant makes about four times more electricity than the old dam's power station did.

Water for People and Farms

The dam helps control the Stanislaus River's flow. This provides an extra 200,000 to 280,000 acre-feet (247 to 345 million m³) of water each year. About 213,000 acres (86,000 ha) of farmland use water from New Melones.

This extra water has helped the region grow. Cities like Tracy and Manteca have expanded. Farmers can grow valuable crops like almonds, walnuts, and grapes.

New Melones Lake is also a popular spot for tourists. People come to boat, fish, and camp. About 800,000 people visit the lake every year. However, during droughts, the lake level can get very low. This sometimes causes parts of the lake to close.

Dam's History

Early Days of the Dam

The Stanislaus River area began to develop with irrigation districts. These were groups that helped farmers get water. The Oakdale and South San Joaquin Irrigation Districts started in 1909. Farmers needed more water, especially in late summer and fall.

In 1926, these two districts built the first Melones Dam. It was a 211-foot (64-meter) high concrete dam. It could store 112,500 acre-feet (139 million m³) of water. But even this wasn't enough, especially during the long droughts of the 1930s.

The irrigation districts wanted a bigger dam. In 1944, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was allowed to build a new, larger dam. This dam would be 355 feet (108 meters) tall. It would hold 450,000 acre-feet (555 million m³) of water. Its main goal was to stop floods. It would protect 35,000 acres (14,000 ha) of farmland and towns like Oakdale.

However, building the dam just for flood control wasn't seen as worth the cost. If other benefits like irrigation and fishing were added, it looked better. But the Corps wanted it mainly for flood control. This was because irrigation projects were usually handled by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

In the 1950s, the irrigation districts built more dams upstream. These were Donnells and Beardsley Dams. The Corps worried these smaller dams would reduce the need for a big New Melones Dam. So, the first New Melones plan was put aside in 1954.

Meanwhile, the irrigation districts suggested an even bigger dam. It would be 460 feet (140 meters) tall and hold 1.1 million acre-feet (1.4 km³) of water.

The Bureau of Reclamation also looked at the Melones dam site. They decided to make the project even larger. This new plan, called "New Melones II," would be part of the Central Valley Project. The Bureau said a bigger lake would provide more water for farming. It would also help other parts of the Central Valley Project. Plus, it would keep enough water in the Stanislaus River for fish.

In 1962, the final design for the dam was approved. It changed from an arch dam to an earth and rock dam. The reservoir size grew to 2.4 million acre-feet (3 km³). A new power plant would also be built. The Corps would build the dam and manage floods. The Bureau would operate it for irrigation and power.

Some people in the early 1960s thought the dam was too big. They worried it might never fill up. There was also concern that the water might be sent outside the local area. So, a rule was added: water would be used locally first, and only extra water could be sent elsewhere.

Then, in 1964, a big flood caused a lot of damage along the Stanislaus River. This showed how much a large dam was needed. With more support, Congress approved funding in 1965. Construction began the next year.

Protests and the Lake's Filling

Building the New Melones Dam caused a lot of protests. People were worried about the beautiful Stanislaus River canyon being flooded.

On May 22, 1979, a man named Mark Dubois chained himself to a rock in the canyon. He wanted to stop the lake from filling. He wrote letters to the dam operators and Governor Jerry Brown. Dubois stayed hidden for five days. Because of his protest, the dam operators stopped filling the lake. The water level was halted at 808 feet (246 meters). This was about 280 feet (85 meters) below its planned maximum level.

Environmental groups wanted a compromise. They suggested keeping the lake level at the old Parrott's Ferry Bridge. This was 844 feet (257 meters) above sea level. It would mean the lake held about 438,000 acre-feet (540 million m³) of water. They said, "We can have a working dam and a wild river."

But the irrigation districts and government officials argued. They said it was silly to build a dam and not fill it. California's state government first agreed with the protesters. In November 1980, they set a temporary limit for the lake level.

For the next two years, the state kept delaying the filling of the reservoir. They wanted proof that the dam's benefits for farming would be greater than the harm to fish and wildlife. Studies showed that completely filling the lake might actually cause some problems. For example, more water might be needed to clean up polluted water from new farms. Also, a very full lake would leave less room for flood control.

The state decided that 623,000 acre-feet (768 million m³) was the best amount of water to store. This would provide enough water for farms and fish. It would also help during droughts and floods.

In the end, nature decided. The winters of 1982 and 1983 were very wet. The Stanislaus River swelled with so much water that the reservoir quickly went past its temporary limit. In 1983, the water reached the very edge of the emergency spillway. It hasn't been that high since.

With the lake full, California lifted the temporary limit in March 1983. The dam had prevented $50 million in damages in 1982 and 1983. This showed how important the dam was for flood control.

Water Challenges

New Melones Dam can hold a lot of water compared to the river that feeds it. The amount of water the dam was expected to provide was based on river flow data from 1922 to 1978. This period might have been wetter than average. The Bureau of Reclamation thought the dam would provide an extra 335,000 acre-feet (413 million m³) of water each year. But the actual amount has been closer to 200,000 acre-feet (247 million m³).

Because of this, the reservoir often has low water levels. Demand for water is usually higher than the supply. Between 1978 and 2016, New Melones only reached its full capacity five times. Only once, in 1983, did it reach the spillway level.

From 1987 to 1992, the Bureau of Reclamation even had to buy water from other places to meet its promises. In October 1992, the reservoir hit a record low. It was only 3.5% full. However, the dam's large storage capacity also means it can capture more floodwater than other dams.

The dam was supposed to provide 1,067,000 acre-feet (1.3 km³) of water. Of this, 600,000 acre-feet (740 million m³) went to the Oakdale and South San Joaquin Irrigation Districts. They owned the original dam and had the oldest water rights. Another 422,000 acre-feet (521 million m³) was for water quality and fish in the Stanislaus River. The Stockton East Water District got 45,000 acre-feet (55 million m³).

New Melones water is also important for refilling underground water sources. This is vital for farmers during droughts. It also helps keep the Stanislaus and San Joaquin Rivers clean by diluting pollution in the dry season.

Water for Fish

Since the 1990s, more water has been needed for environmental flows. This means releasing water to help fish, especially Chinook salmon and steelhead trout. This sometimes goes against the original plan for the dam.

One new requirement is for "pulse flows" in spring and autumn. These are sudden releases of water to help fish migrate. Farmers criticize this, saying it wastes water in dry years. They point out that fish populations still struggle. But officials say these flows are needed to meet state and federal rules.

Another problem is keeping the water cold enough for fish in autumn. Cold water needs to be released from the deepest parts of the reservoir. But the old Melones Dam was not removed. It is still underwater and can block the cold water from flowing out. This means warmer surface water might be released instead. So, sometimes less water is given to farms to keep enough cold water for the fish.

A 2016 study found that these artificial spring water releases don't help salmon and steelhead much. Fish naturally move when it rains. In 2016, few young salmon migrated during the special water release. If water is released in spring during a drought, there might not be enough cold water left for fish to spawn in the autumn.

California has suggested letting 20% to 60% of the river's natural flow go downstream in spring for fish. Also, New Melones Lake would always have to keep at least 700,000 acre-feet (863 million m³) of water. This would protect the cold water for fish. But this plan would limit how much water the dam can store for other uses.

Local cities and farmers are very concerned. They say this plan would hurt farming and cause many jobs to disappear. They also point out other problems, like striped bass in the San Joaquin River. These fish eat many young salmon and steelhead.

Finding Solutions

In 2015, Congressman Tom McClintock tried to pass a law. It would stop applying the Endangered Species Act to water releases during droughts. He mentioned that 30,000 acre-feet (37 million m³) of water was released from New Melones in spring 2015. This was when the lake was very low. He argued that this water helped very few fish. However, the bill did not pass.

A possible solution was discussed in a 2016 agreement. Local water districts would provide 75,000 acre-feet (92.5 million m³) of water for fish in the spring. This water would then be sold to another water authority. Instead of flowing into the ocean, it would be captured and reused for farming. This way, water can help fish and still be used for agriculture.

Dam's Impact

The debate over New Melones Dam was one of the biggest environmental fights in the U.S. at the time. The dam was built when more people cared about protecting nature. Friends of the River, an environmental group, calls the fight against the dam "probably the biggest citizen effort to save a river and stop a dam in American history." Even the Bureau of Reclamation has called New Melones "a case study of all that can go wrong with a project."

Even though the dam's opponents didn't stop it, their efforts made the river conservation movement much stronger. In California, many later dam projects were stopped by people's protests. This included a power project on the nearby Tuolumne River.

A book called Dam Politics: Restoring America's Rivers says:

The New Melones Dam was one of the last of its kind. No other structure as large or as important has been built on an American river since. And since this date, almost no changes to a river in this country have gone unopposed.

The New Melones debate helped protect other rivers in Northern California. Rivers like the Eel and Klamath were added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System starting in 1980. The debate also changed how California's government thought about water. They started focusing more on saving water and improving policies, instead of just building huge dams.

In 1982, a new law called the Reclamation Reform Act set stricter rules for federal dam projects. This moved away from building "dams-everywhere." However, the lack of new water storage has put a lot of strain on California's water system. California now has 15 million more people than when New Melones Dam was finished in 1979.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |