Tuolumne River facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tuolumne River |

|

|---|---|

The Tuolumne River at Glen Aulin valley, below Tuolumne Meadows

|

|

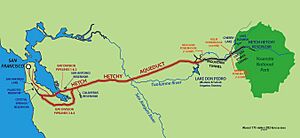

The Tuolumne River watershed

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Confluence of Lyell and Dana Forks Tuolumne Meadows, Yosemite National Park 8,589 ft (2,618 m) 37°52′31″N 119°21′08″W / 37.87528°N 119.35222°W |

| River mouth | San Joaquin River Grayson, Stanislaus County 26 ft (7.9 m) 37°36′21″N 121°10′25″W / 37.60583°N 121.17361°W |

| Length | 148.7 mi (239.3 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 1,958 sq mi (5,070 km2) |

| Tributaries |

|

| Type: | Wild, Scenic, Recreational |

| Designated: | September 28, 1984 |

The Tuolumne River (in the Yokutsan language: Tawalimnu) flows for about 149 miles (240 km) through Central California. It starts high in the Sierra Nevada mountains and joins the San Joaquin River in the Central Valley. The river begins over 8,000 feet (2,400 m) above sea level in Yosemite National Park. It drains a large area of 1,958 square miles (5,070 km2), carving deep canyons through the western side of the Sierra.

The upper Tuolumne is a fast-moving mountain stream. But the lower river flows across a wide, flat, and very fertile plain called an alluvial plain. This area is used a lot for farming. Like many rivers in central California, the Tuolumne has several dams. These dams help with irrigation (watering crops) and making hydroelectricity (power from water).

People have lived near the Tuolumne River for up to 10,000 years. Before Europeans arrived, the river canyon was an important place for summer hunting. It was also a trade route for Native Americans between the Central Valley and the Great Basin. A Spanish explorer first named the river in 1806 after a nearby village. In the 1850s, during the California Gold Rush, many people searched for gold in the Tuolumne area. Over the next few decades, American settlers farmed the lower valley. The city of Modesto grew along the Tuolumne as a railroad center.

From the 1900s to the 1930s, dams were built on the river at Don Pedro and Hetch Hetchy. These dams provided water for farmers in the Central Valley and for the city of San Francisco. The Hetch Hetchy project was built inside Yosemite National Park. This caused a big argument across the country. Many people say it helped start the modern environmental movement in the United States. As time went on, more water was needed from the Tuolumne. This led to the building of the New Don Pedro Dam in the early 1970s. These dams cut the amount of water flowing into the San Joaquin River by half. This greatly reduced the number of salmon and steelhead fish that used to live in both rivers.

Contents

Where Does the Tuolumne River Flow?

The Tuolumne River starts in Yosemite National Park, high in the Sierra Nevada mountains. It begins as two streams. The Lyell Fork is about 7-mile (11 km) long. It starts at the Lyell Glacier below Mount Lyell, which is the highest peak in Yosemite. This fork flows north through Lyell Canyon. The Dana Fork is about 5-mile (8.0 km) long. It starts between Mount Dana and Mount Gibbs and flows west.

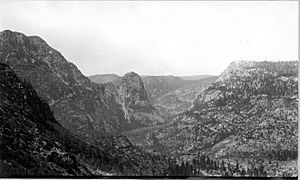

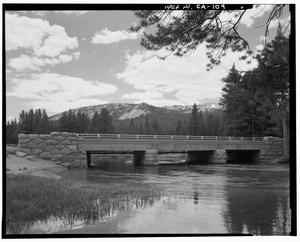

After these two forks meet in Tuolumne Meadows, the river flows northwest. It passes under Tioga Road. The river is calm for a few miles, but then it quickly drops over Tuolumne Falls and White Cascades. After a short time in Glen Aulin, the river enters the amazing 20-mile (32 km) Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne. Here, it forms three more big waterfalls: California, LeConte, and Waterwheel Falls. Return and Piute Creeks join the river from the north inside the Tuolumne Canyon.

At the end of the canyon, the river widens into Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. This reservoir was made by a dam built in 1923. It provides water to San Francisco. Falls Creek creates Wapama Falls and Tueeulala Falls, two of Yosemite's tallest waterfalls, as it flows into the reservoir. From its start at 8,589 feet (2,618 m) in Tuolumne Meadows, the river drops almost a mile (1.6 km) to Hetch Hetchy reservoir at 3,800 feet (1,200 m).

Below the O'Shaughnessy Dam, the Tuolumne flows through Poopenaut Valley. It then enters a series of canyons as it goes through the Sierra foothills. It leaves Yosemite National Park and enters the Stanislaus National Forest. Most of the Tuolumne's main smaller rivers (tributaries) join it here. First is Cherry Creek from the north. Then the South Fork of the Tuolumne joins from the south, near Groveland-Big Oak Flat. After that, the Clavey River joins from the north. The North Fork of the Tuolumne joins near the upper part of Lake Don Pedro. This lake was formed in 1971 when the New Don Pedro Dam was built. It helps make electricity and store water for farming. Right below Don Pedro Dam is the La Grange Dam. Here, about half of the river's natural flow is sent into canals. These canals, the Turlock and Modesto Main Canals, water over 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of farmland in the Central Valley.

After leaving the foothills, the Tuolumne flows about 50 miles (80 km) west across the Central Valley. It passes through towns like Waterford, Hughson, Empire, Ceres, and Modesto. The lower Tuolumne is wide and flows slowly. It drops only 230 feet (70 m) from La Grange Dam to where it meets the San Joaquin River. Highway 99 and the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks cross the river in Modesto. The Modesto Airport is also next to the river. Dry Creek joins the Tuolumne from the north. The Tuolumne and San Joaquin rivers meet in the San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge. This is about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Grayson in Stanislaus County.

How Much Water Flows in the Tuolumne?

The Tuolumne is the biggest river flowing from the southern Sierra Nevada mountains. It naturally carries about 1,850,000 acre-feet (2.28 km3) of water each year. This is more than 2,550 cubic feet per second (72 m3/s). Near the end of the river, the most water ever recorded in a year was 3,995,000 acre-feet (4.928 km3) (or 5,518 cubic feet per second (156.3 m3/s)) in 1983. The least was 134,000 acre-feet (0.165 km3) (or 185 cubic feet per second (5.2 m3/s)) in 1977. That's a huge difference!

Most of the river's water comes from melting snow in the summer. But very big floods can happen after heavy winter storms. The natural flow of the Tuolumne is much less now. This is because water is taken out for San Francisco's Hetch Hetchy water system. Water is also taken for the Modesto and Turlock irrigation canals.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) measures the river's flow. Today, the most water flows in the short part of the river between Don Pedro Dam and La Grange Dam. This is about 50 miles (80 km) from the river's end, before a lot of water is taken for farming. A USGS station here measured an average flow of 2,343 cubic feet per second (66.3 m3/s) between 1911 and 1970. The highest flow recorded was 60,300 cubic feet per second (1,710 m3/s) on January 31, 1911. The lowest monthly average was 57.5 cubic feet per second (1.63 m3/s) in October 1912. During the Great Flood of 1862, the river's flow was estimated to be 130,000 cubic feet per second (3,700 m3/s). This happened after a record 72 inches (1,800 mm) of rain fell in the Tuolumne River area.

Further downstream, near Modesto, another USGS station measured an average flow of 1,326 cubic feet per second (37.5 m3/s) between 1940 and 2013. The highest flow there was 57,000 cubic feet per second (1,600 m3/s) on December 9, 1950. The lowest was 56 cubic feet per second (1.6 m3/s) on August 6, 1977.

What is the Tuolumne River Watershed Like?

Different Parts of the Watershed

The Tuolumne River watershed (the area of land that drains into the river) has three main parts. From its start to below Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, the river flows through the high Sierra mountains. This area has hard, glacier-carved rocks, thin soils, and many forests. Most of the snow that feeds the Tuolumne falls here. The streams are usually fast, clear, and rocky. But large alpine meadows provide wet areas where plants and animals live. These meadows also add sediment to the river's flow. There are many natural lakes in the upper watershed. The Sierra peaks have several glaciers, like Lyell and Maclure Glaciers. These are the largest in Yosemite National Park. Melting ice from these glaciers feeds the upper Tuolumne River. This keeps water flowing in late summer when other streams might dry up.

Between Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and Lake Don Pedro, the Tuolumne flows through the Sierra foothills. Here, the river flows less steeply but is still fast. There are more pools and gravel bars, allowing plants to grow along the riverbanks. By the time the river reaches Lake Don Pedro, it has collected almost 90 percent of its water. This water comes from rain, snowmelt, and groundwater (water from underground).

Below Don Pedro Dam, the river flows across the large alluvial plain of the San Joaquin Valley. This plain was formed over millions of years by dirt and rocks washed down from the Sierra. In the past, this part of the river often changed its path. It also created thousands of acres of seasonal wetlands during spring floods. Now, because of large-scale farming, the Tuolumne River's path is fixed between many levees (raised banks). More than 300,000 acres (120,000 ha) in the San Joaquin Valley are watered using Tuolumne River water.

About 669 square miles (1,730 km2), or 34 percent, of the Tuolumne River watershed is inside Yosemite National Park. Other rivers near the Tuolumne's watershed include the Stanislaus River and West Walker River to the north. To the south is the Merced River. To the northeast is the East Walker River. The Mono Lake basin (with Mill Creek, Lee Vining Creek, and Rush Creek) is to the east. And the start of the San Joaquin River is to the southeast.

What Are the Main Streams Joining the Tuolumne?

Here are the major streams that flow into the Tuolumne River, listed from its start to its end:

| Name | Coordinates | Elevation | Distance from mouth |

Length | Watershed | Discharge | Bank | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dana Fork Tuolumne River | 37°52′31″N 119°21′08″W / 37.87528°N 119.35222°W | 8,589 ft (2,618 m) |

149 mi (240 km) |

5 mi (8 km) |

R |  |

||

| Lyell Fork Tuolumne River | 37°52′31″N 119°21′08″W / 37.87528°N 119.35222°W | 8,589 ft (2,618 m) |

149 mi (240 km) |

7 mi (11 km) |

L |  |

||

| Return Creek | 37°55′55″N 119°27′58″W / 37.93194°N 119.46611°W | 6,204 ft (1,891 m) |

139 mi (224 km) |

14 mi (23 km) |

R | |||

| Piute Creek | 37°55′48″N 119°36′03″W / 37.93000°N 119.60083°W | 4,344 ft (1,324 m) |

130 mi (209 km) |

20 mi (32 km) |

R | |||

| Rancheria Creek | 37°57′12″N 119°43′41″W / 37.95333°N 119.72806°W | 3,796 ft (1,157 m) |

121 mi (195 km) |

24 mi (39 km) |

R |  |

||

| Falls Creek | 37°57′47″N 119°45′55″W / 37.96306°N 119.76528°W | 3,783 ft (1,153 m) |

119 mi (192 km) |

23 mi (37 km) |

R |  |

||

| Cherry Creek | 37°53′19″N 119°58′19″W / 37.88861°N 119.97194°W | 2,162 ft (659 m) |

104 mi (167 km) |

42 mi (68 km) |

234 mi2 (607 km2) |

694 cfs (19.7 m3/s) |

R |  |

| South Fork Tuolumne River | 37°50′25″N 120°02′52″W / 37.84028°N 120.04778°W | 1,447 ft (441 m) |

96 mi (155 km) |

31 mi (50 km) |

164 mi2 (425 km2) |

167 cfs (4.7 m3/s) |

L |  |

| Clavey River | 37°51′50″N 120°06′59″W / 37.86389°N 120.11639°W | 1,178 ft (359 m) |

91 mi (147 km) |

42 mi (68 km) |

157 mi2 (407 km2) |

255 cfs (7.2 m3/s) |

R | |

| North Fork Tuolumne River | 37°53′49″N 120°15′14″W / 37.89694°N 120.25389°W | 853 ft (260 m) |

81 mi (130 km) |

36 mi (58 km) |

54 cfs (1.5 m3/s) |

R | ||

| Woods Creek | 37°50′45″N 120°22′41″W / 37.84583°N 120.37806°W | 791 ft (241 m) |

68 mi (109 km) |

28 mi (45 km) |

R | |||

| Dry Creek | 37°53′49″N 120°15′14″W / 37.89694°N 120.25389°W | 46 ft (14 m) |

10 mi (16 km) |

63 mi (101 km) |

R |

How is the Land Used Around the River?

Almost 80 percent of the Tuolumne River watershed is above the New Don Pedro Dam. This area is mostly forest, with some alpine (high mountain) areas, meadows, and grasslands. The lower part of the Tuolumne River watershed is mainly used for farming. There are also some big cities. Even though only about 68,000 acres (28,000 ha) (5.4 percent) of the watershed itself is farmed, river water is used to water almost five times that much land outside the watershed. About 16,500 acres (6,700 ha) (1.3 percent) of the watershed is city area, mostly around Modesto. About 550,000 people live in the Tuolumne River watershed, with about 210,000 living in Modesto.

How Do Dams and Engineering Help Control the River?

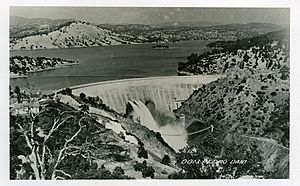

Like most rivers in the Sierra Nevada, the Tuolumne has many dams. These dams help control floods, provide water, and create hydroelectric power. The highest dam is the O'Shaughnessy Dam. It holds back the 360,000-acre-foot (440,000,000 m3) Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. This reservoir provides water and power to San Francisco. The Hetch Hetchy hydroelectric system sends large amounts of water through tunnels. These tunnels feed two power plants, Kirkwood and Moccasin. The power system works well because the Tuolumne drops over 2,750 feet (840 m) between Hetch Hetchy and the Moccasin Powerhouse.

However, this also means that parts of the Tuolumne River have less water, especially in dry summers. This is because almost all the water is sent through the power plants, except for a small amount released for fish. Not all the water used by the power plants returns to the river. About 244,000 acre-feet (301,000,000 m3) of water each year flows through the Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct. This water goes to San Francisco and other cities. The water from Hetch Hetchy is so clean that it doesn't need to be filtered. This is rare for big cities in the United States.

Cherry Creek, the Tuolumne's biggest tributary, is also part of San Francisco's hydroelectric system. Cherry Creek is dammed at the Cherry Valley Dam. This dam creates the 274,000-acre-foot (338,000,000 m3) Cherry Lake. Another important stream, Eleanor Creek, is dammed to form Lake Eleanor. Its water is sent into Cherry Lake through a tunnel. The combined water then goes through a pipe and returns to the river at the Holm Powerhouse. Unlike the Hetch Hetchy system, the Cherry Creek system is only used for making power, not for water supply. This is because its water quality is not quite as good. However, there is a connecting pipe that allows Cherry Lake water to be used by the Hetch Hetchy system during very dry times. This backup water supply was last used in late 2015 for testing.

Below where the North Fork of the Tuolumne joins, the river flows into Lake Don Pedro. This is the largest lake in the Tuolumne River system. It is also the sixth-largest man-made lake in California, holding 2,030,000 acre-feet (2.50×109 m3) of water. The New Don Pedro Dam is an earth-filled dam, 585 feet (178 m) high. It is the 10th tallest dam in the United States. It was built for many purposes: irrigation, city water supply, hydropower, and flood control. It replaced an older concrete dam in the same area.

The Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts control most of the water in the reservoir. San Francisco also has rights to store water here. They use this water mainly to make up for water taken upstream at Hetch Hetchy. Only 340,000 acre-feet (420,000,000 m3) of the reservoir is set aside for flood control. This is a small amount compared to other reservoirs in California. Because of this, Don Pedro often fills up and overflows during winter storms, which can cause damage downstream.

The La Grange Dam is a much smaller dam. It is the last dam on the Tuolumne before it joins the San Joaquin River. The Modesto Canal (on the north side) and Turlock Canal (on the south side) are both large canals for irrigation. The Modesto Canal fills the 29,000-acre-foot (36,000,000 m3) Modesto Reservoir, which helps distribute water to farmers. Turlock Lake is similar but much larger, with a capacity of 49,000-acre-foot (60,000,000 m3). About 867,000 acre-feet (1.069×109 m3) of water is taken for irrigation each year. This is about half of the Tuolumne River's natural flow.

Below La Grange, the Tuolumne River has much less water due to irrigation. It flows through a fixed channel with a very small floodplain (the flat land next to the river that floods). Before farming, the river would flood large areas of seasonal marshland. It could also change its path often. Today, farms and towns are protected by a levee system. The river channel can hold about 9,000 cubic feet per second (250 m3/s) at the 9th St. Bridge in Modesto. This is much less than the river's biggest flood potential. The valley relies on Lake Don Pedro to control floods. However, the river has still flooded many times. A famous flood was the New Year's Flood of 1997. During this flood, water flowing into Don Pedro reached 120,000 cubic feet per second (3,400 m3/s). This was the largest amount recorded since the Great Flood of 1862. Water released from Don Pedro Dam peaked at 60,000 cubic feet per second (1,700 m3/s). While this greatly reduced damage, it was still six times more than the channel could hold. This caused a lot of property damage along the river.

What Animals and Plants Live Here?

The Tuolumne River used to have many chinook salmon (also called king salmon) and steelhead trout. In its natural state, the fall Chinook salmon run alone might have had as many as 130,000 fish. This is the southernmost group of Chinook salmon in North America, except for the Merced River to the south. But large water diversions and river changes have caused the spring Chinook run to disappear. The fall run has also greatly decreased. Dams have blocked more than half of the original 99 miles (159 km) of spawning habitat (places where fish lay eggs) for migratory fish in the Tuolumne River watershed. The San Joaquin River and the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, which connect the Tuolumne salmon to the Pacific Ocean, have also been affected by less water and pollution.

Also, new species like striped bass eat young salmon. They can eat as much as 93 percent of the young fish before they can swim to the sea. Around 2013, a plan was suggested to increase spring and summer water flows on the Tuolumne River. This would help native anadromous fish (fish that swim from the sea to freshwater to breed). But it would also greatly reduce the water available for farms and cities. Farming groups argue that fish being eaten by other fish, not low water flows, is the main reason for salmon deaths.

The forests in the watershed have different types of trees. The foothill area has trees and plants that can handle hot, dry weather. These include chamise (greasewood), California lilac, manzanita, blue oak, interior live oak, and gray pine. Further east and higher up are the lower and upper montane forests. These are between 3,000 to 6,000 feet (910 to 1,830 m) and 6,000 to 8,000 feet (1,800 to 2,400 m) high. The lower montane forests have black oak, ponderosa pine, incense cedar, and white fir. Higher up, you'll find Jeffrey pine and western juniper. Even higher is the subalpine forest zone, between 8,000 to 9,500 feet (2,400 to 2,900 m). This area has mostly Western white pine, mountain hemlock, and lodgepole pine. Above 9500 feet, only small shrubs, flowering plants, and some whitebark pine grow. This alpine zone is only on the peaks around Tuolumne Meadows and along the Sierra Crest.

Humans have changed the natural conditions in the Tuolumne River watershed for hundreds of years. Native Americans used to set controlled fires in grasslands. This cleared out dead plants and allowed new growth. This new growth attracted animals like deer. They also burned oak woodland areas in the foothills to control pests. This protected their main food source, acorns. During the Spanish and Mexican times, the Central Valley was used for cattle ranching. This quickly destroyed the natural grasses. In the 1880s, American sheep ranchers brought their sheep to the upper Tuolumne River watershed for summer grazing. This further damaged the land in the foothills and Sierras. Hetch Hetchy Valley was one of the main summer grazing areas for sheep.

The loss of native perennial grasses caused invasive annual plants to grow widely. It also made the watershed more likely to have wildfires. To protect property and the watershed, people started to stop fires in the early 1900s. But this led to too many plants growing. It also stopped the natural forest succession process that wildfires used to control.

What is the Early History of the Tuolumne River?

People may have first lived along the Tuolumne River between 3000 and 7000 BC. The Plains and Sierra Miwok were the largest Native American group in the area before Europeans arrived. They settled here around 1200 CE. The Miwok lived in the Sierra foothills and Central Valley lowlands during winter. In summer, they traveled into the upper Tuolumne River area to hunt and escape the heat. The Paiute, who lived east of the Sierra, also came into the Tuolumne River basin in the summer. The Yokuts lived along the lower Tuolumne River and usually did not go up into the Sierra in summer.

The Hetch Hetchy Valley was a main meeting place for the Paiute and Miwok. It had many edible plants and animals. The name "Hetch Hetchy" might come from a type of edible grass that grew in the valley. Native peoples used this grass to make flour. They set controlled fires to clear old plants in their gathering areas. This made it easier to harvest new growth. It also helped grasses and ferns grow, which attracted animals like deer. This made the landscape easier to travel through. Many areas in the Tuolumne River region that the first European explorers saw were not untouched. They were the result of hundreds of years of management by Native Americans. The famous meadows of Hetch Hetchy Valley, before the dam, only existed because of these yearly burns.

The origin of the Tuolumne River's name is not fully clear. The Spanish explorer Gabriel Moraga first recorded the name "Tuolumne" in 1806. He might have named the river after a nearby Native American village called Tualamne or Tautamne. This name might come from the native word talmalamne, meaning "a group of stone huts or caves." Father Pedro Muñoz, who was with the 1806 expedition, wrote in his diary that they found "a village called Tautamne. This village is on some steep cliffs, hard to reach because of their rough rocks. The Indians live in their sótanos [cellars or caves]." At this time, about two thousand Native Americans lived along the lower Tuolumne and Stanislaus Rivers.

Another idea for the name Tuolumne is the Central Sierra Miwok word taawalïmi, meaning "squirrel place." This refers to a Native American village on the nearby Stanislaus River. The ending -umne, found in other California river names like the Mokelumne and Cosumnes, is thought to have meant "place of" or "people of" in the native language.

The Tuolumne River was a very active place for gold mining during the California Gold Rush. The first gold in the area was found by Benjamin Wood in the summer of 1848. By late 1848 and early 1849, mining camps like Jamestown, Tuttletown, and Don Pedros Bar were set up along the Tuolumne. The next spring, Mexican miners found even richer gold upstream. They started Sonoranian Camp, which became the town of Sonora, California. By the end of 1849, over 10,000 miners were in the Tuolumne River area. Sonora became the county seat in 1850.

Mining grew a lot in the early 1850s. In March 1850, a "very rich" gold deposit was found at Columbia. That same year, the Bonanza Mine near Sonora found a 1500-ounce gold nugget. This was the fourth largest ever found in California. The success in the region led to a search for a new way to cross the Sierra Nevada. This new route would give more direct access to the camps from the east. The Clark-Skidmore Party crossed in 1852 using the upper Stanislaus River and the north fork of the Tuolumne. Parts of their route later became the Walker River Trail, known as one of the harder Sierra crossings.

For a short time, the lower Tuolumne was a major steamboat route. Steamboats carried miners and supplies from Stockton. About 35 miles (56 km) of the lower river could be used by boats, from its mouth to above Waterford. The river's unpredictable nature made both boating and crossing difficult. So, many ferries were set up during the Gold Rush. One of the first was Dickenson's Ferry in the early 1850s. This spot was where Fort Miller Road crossed. This was a major trade route connecting Stockton with Millerton (now the site of the Millerton Lake reservoir).

By 1853, most of the easy-to-find gold was gone. Hydraulic mining (using powerful water jets to wash away hillsides) became the main way to get gold. The Tuolumne County Water Company, started in 1851, built a system of reservoirs, ditches, and flumes. These were first used for mining and later for irrigation. The Golden Rock Water Company, started in 1855, diverted the South Fork of the Tuolumne. This supplied gold diggings at Groveland and Big Oak Flat. Their biggest project was building a 2,200-foot (670 m) long, 265-foot (81 m) high aqueduct (the Big Gap Flume) over Buck Meadows. The first dam on the Tuolumne River itself, near La Grange, was built in 1852 for hydraulic mining. Dirt and rocks washed down by hydraulic mining built up along the lower Tuolumne. This destroyed natural floodplain habitats and made much of the river impossible to navigate.

How Have Dams Changed the River?

La Grange and Old Don Pedro Dams

After the gold rush, many miners became farmers along the lower Tuolumne River. Ferry sites grew into busy towns like Waterford. The town of Tuolumne City was founded near the mouth of the Tuolumne as a port. But it soon became clear that mining debris made the river unsuitable for boats, so the area was abandoned. In the mid-1860s, Tuolumne City and Paradise (about 5 miles (8.0 km) upstream) were restarted as farming communities. The founding of Modesto in 1870, along a new railroad, drew most people away from these towns. By the early 1900s, Modesto had over four thousand people.

It became clear that the Central Valley's seasonal rainfall made it hard to farm without irrigation. So, farmers created groups to build irrigation systems along the Tuolumne River. The Turlock Irrigation District (TID), started in 1887, was the first irrigation district in California. The Modesto Irrigation District (MID) started soon after in the same year. These two districts serve the south and north sides of the river. The current La Grange Dam, finished in 1893, replaced the older mining dam at the same spot. At 122 feet (37 m), it was the highest overflow dam in the United States. The dam sent river water into canals that watered most of the lower valley. The first TID farmers got water in 1900. The MID canal took thirteen years to build, with water deliveries starting on June 27, 1903.

As the population grew, the Tuolumne River districts started to have water shortages during certain seasons. The Dallas-Warner Reservoir (now Modesto Reservoir) was finished in 1912. But it was only a temporary solution. Construction on the first Don Pedro Dam began in 1921. This dam was meant to store floodwaters from the Tuolumne. This would allow for a longer irrigation season and provide water during dry years. Another reason for the dam was that TID and MID knew San Francisco wanted water from the Tuolumne. Even though the irrigation districts had the first rights to the Tuolumne's water, they could lose those rights if they didn't use the water fully. So, they needed to build storage to use the river water completely. The Don Pedro dam was finished in 1923, holding back 289,000 acre-feet (0.356 km3) of water. In 1923 and 1924, both Don Pedro and La Grange dams were set up to generate hydroelectricity.

The Hetch Hetchy Project

San Francisco didn't start plans to divert the Tuolumne until the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fires. These events showed that the city's water system wasn't good enough. After looking at fourteen sites in Central California, San Francisco chose the Tuolumne's Hetch Hetchy Valley. It seemed like the perfect place to store water and make hydroelectric power. Since the area was inside Yosemite National Park since 1890, the city asked Congress to pass the Raker Act. This Act was signed in 1913 by President Woodrow Wilson. It allowed San Francisco to dam the Tuolumne River, but only if the water and power were used for public benefit, not for private sale.

The Hetch Hetchy Valley became the center of the first big environmental argument in the United States. John Muir, the leader of the Sierra Club, led a legal fight against the proposed O'Shaughnessy Dam. He famously said, "Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the peoples' cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man." The Hetch Hetchy debate is often seen as the start of modern environmentalism. It sharply divided the conservation movement (who wanted to use natural resources for public good) and the preservationists (who believed beautiful places like Hetch Hetchy should be left untouched for people to enjoy).

Despite the arguments, San Francisco went ahead with the project. Construction began in early 1914, and the reservoir was filled for the first time in May 1923. The Hetch Hetchy Railroad was built along 68 miles (109 km) of the Tuolumne River Canyon. This helped bring materials to the remote construction site. Hydroelectric power reached San Francisco by 1925, but water wasn't delivered until 1934. Today, San Francisco diverts about 33 percent of the Tuolumne's flow at Hetch Hetchy. This is about 14 percent of the river's total flow.

New Don Pedro Dam and Modern Changes

By the mid-1900s, it was clear that the Tuolumne River reservoirs couldn't hold enough water for growing needs. The Don Pedro irrigation dam could only store enough water for one growing season. This meant little water was left for drought years, and it didn't help much with flood control. In the late 1950s, TID and MID started planning for a new, taller dam on the Tuolumne River. This new dam would be several miles below the old Don Pedro Dam. In 1961, voters approved money to fund the project. However, it took until 1966 for the Federal Power Commission (now FERC) to approve the project. Concerns that the new dam would harm king salmon populations were the main reason for the delay.

Construction of the new dam began in 1967. The river was diverted in September 1968. The dam was finished on May 28, 1970. The project was officially opened on May 22, 1971. It took four years to build and cost over $110 million. It took eleven more years for the new reservoir, which holds 2,030,000 acre-feet (2.50 km3) of water (ten times the size of Old Don Pedro), to fill completely in June 1982. The reservoir covered 25 miles (40 km) of the middle Tuolumne River and 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) of land around it. This included the historic Gold Rush town of Jacksonville.

What Can You Do for Fun on the Tuolumne River?

The Tuolumne River watershed gets over a million visitors each year. Most people visit the protected wilderness areas of Yosemite National Park. They also enjoy the challenging but popular whitewater rafting on the Main Tuolumne and Cherry Creek.

The Tuolumne is known as a great place for whitewater rafting in California. People have been rafting here since the 1960s. Most rafters start at Meral's Pool, about 2 miles (3.2 km) below Cherry Creek. They then raft for 18-mile (29 km) to Lake Don Pedro. Several rafting companies offer trips on the main Tuolumne. It is a Class IV+ (advanced) river with many rapids. These rapids can become Class V (very difficult) when the water flow is over 4,000 cubic feet per second (110 m3/s). The hardest single rapid is Clavey Falls. The longest is Grey's Grindstone, which is almost a mile (1.6 km) long. Between these two rapids, the swimming holes of the Clavey are a popular camping spot in the summer.

Cherry Creek also has commercial rafting trips. It is considered one of the most difficult whitewater rivers in the United States, with fifteen Class V rapids. Both the Tuolumne and Cherry Creek runs are controlled by dams. This usually means the rafting season can last longer, even through the dry late summer and fall.

In Yosemite National Park, the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne (from Tuolumne Meadows to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir) was first kayaked in 1983. This 32-mile (51 km) section is rated Class IV-V+. It has many waterfalls that require kayakers to carry their boats around them. Besides being extremely difficult, the water flow depends entirely on rain and melting snow. So, the whitewater season can be very short in dry years. Most people agree that the best paddling is in the upper miles. The middle section is better for hikers and canyoneers.

The Clavey River is not in the national park, so it is open to the public. But it is remote and very difficult (Class V+). Also, the short time when spring runoff makes it runnable means only a few kayakers go there each year.

To protect the river, the U.S. Forest Service requires private groups to get a permit before floating the Tuolumne. Rafting the Tuolumne inside Yosemite National Park was also a bit unclear legally until 2015. That year, the park allowed limited paddling and rafting on the Tuolumne and Merced Rivers.

What About Wildfires?

In 2013, the Rim Fire burned 257,314 acres (104,131 ha). At the time, this huge fire was California's third largest wildfire ever recorded. This wildfire destroyed homes for many native and endangered animals and plants. It also affected fun activities, communities, and local businesses.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Río Tuolumne para niños

In Spanish: Río Tuolumne para niños