Hetch Hetchy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hetch Hetchy Valley |

|

|---|---|

|

Top: Hetch Hetchy Valley in the early 1900s, before the dam was built. You can see Wapama Falls on the left and Kolana Rock on the right. Bottom: A recent photo from the same spot, showing the valley floor now covered by the reservoir.

|

|

| Floor elevation | 3,783 ft (1,153 m) |

| Length | 3 mi (4.8 km) |

| Width | 0.5 mi (0.80 km) |

| Area | 1,200 acres (490 ha) |

| Depth | 1,800 ft (550 m) |

| Geology | |

| Type | Glacial |

| Age | 10,000–15,000 years |

| Geography | |

| Location | Yosemite National Park, California, United States |

| River | Tuolumne River |

Hetch Hetchy is a special place in California, United States. It's a valley, a large lake (called a reservoir), and a water system. The Hetch Hetchy Valley is located in the northwestern part of Yosemite National Park. The Tuolumne River flows through it.

For thousands of years, Native Americans lived in the valley. They hunted and gathered food. In the late 1800s, people admired the valley's natural beauty. Many compared it to the famous Yosemite Valley. However, some also wanted to use its water for cities and farms.

The decision to build a dam in Hetch Hetchy became a big debate. It involved many political issues and lasted for years. This debate showed how much the country was changing during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Powerful people, like newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst, influenced the public. In 1913, the Raker Act was passed by Congress, allowing the dam to be built.

In 1923, the O'Shaughnessy Dam was finished. It flooded the valley, creating the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. This dam and reservoir are key parts of the Hetch Hetchy Project. Since 1934, the project has sent water 167 miles (269 km) west to San Francisco and other nearby cities.

Contents

Exploring Hetch Hetchy's Landscape

Before the dam, Hetch Hetchy Valley was very deep. It was about 1,800 ft (550 m) deep on average, and up to 3,000 ft (910 m) in some spots. The valley was 3 mi (4.8 km) long and about 0.5 mi (0.80 km) wide. Its floor had 1,200 acres (490 ha) of meadows surrounded by pine trees. The Tuolumne River and many smaller streams flowed through these meadows.

Kolana Rock is a huge rock spire on the south side of the valley. It stands 5,772 ft (1,759 m) tall. Hetch Hetchy Dome is directly north of it, at 6,197 ft (1,889 m). These rocks are like El Capitan and Cathedral Rocks in Yosemite Valley.

The valley gets its water from the Tuolumne River, Falls Creek, and other streams. These streams drain a large area of 459 sq mi (1,190 km2). Before the dam, the valley floor was often wet and flooded in spring. This happened when melting snow from the Sierra Nevada mountains flowed down the Tuolumne River. Now, the valley is covered by about 300 ft (91 m) of water. But during very dry years, like 1955, 1977, and 1991, parts of the valley floor can be seen again.

Upstream from the valley is the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne. Downstream from the dam is the smaller Poopenaut Valley. The Hetch Hetchy Road leads to the dam. Beyond the dam, you can only explore by hiking or riding horses. The reservoir stretches eastward for about 8 miles (13 km).

Two tall waterfalls are in Hetch Hetchy Valley: Wapama Falls (1,080 ft (330 m)) and Tueeulala Falls (840 ft (260 m)). Both are among the tallest in North America. Rancheria Falls is further southeast. There was also a waterfall on the Tuolumne River itself, but it is now underwater.

How Hetch Hetchy Was Formed

Hetch Hetchy Valley started as a V-shaped canyon carved by the Tuolumne River. About one million years ago, huge glaciers (large sheets of ice) moved through the area. These glaciers made river valleys wider, deeper, and straighter. This is how Hetch Hetchy, Yosemite Valley, and Kings Canyon were shaped.

During the last glacial period, a glacier called the Tioga Glacier formed. It was up to 4,000 ft (1,200 m) thick and filled Hetch Hetchy Valley. As the ice moved, it carved the valley into its current smooth, rounded shape. When the glacier melted, it left behind thick layers of dirt and sand. This formed the flat floor of the valley.

Hetch Hetchy's walls are smoother than Yosemite Valley's. This is because more ice flowed through Hetch Hetchy. The area that feeds the Tuolumne River above Hetch Hetchy is almost three times larger than the area that feeds the Merced River above Yosemite. This allowed a much larger glacier to form in Hetch Hetchy.

Plants and Animals of Hetch Hetchy

Hetch Hetchy is home to many different plants and animals. You can find trees like gray pine, incense-cedar, and California black oak. Red-barked manzanita plants grow along the Hetch Hetchy Road. In spring and early summer, wildflowers like lupine, wallflower, and buttercup bloom. Seventeen types of bats live in the area, including the large western mastiff bat.

Before the dam, the valley floor had many black oaks, live oaks, Ponderosa pines, and Douglas firs. Along the Tuolumne River, there were alders, willows, and dogwoods. The valley's rich plant life provided food for animals like mule deer, black bears, and bighorn sheep.

Early travelers often found Hetch Hetchy full of mosquitoes in the summer. One person in 1918 said, "The first time I went into the Hetch Hetchy the mosquitoes were intolerable. They would light upon a man's blue shirt and turn it brown."

History of Hetch Hetchy

Native American Life

People have lived in Hetch Hetchy Valley for over 6,000 years. Native American groups, like the Miwok and Paiute, visited the valley in summer. They came from the Central Valley and the Great Basin. The valley offered a cool escape from the summer heat. They hunted and gathered seeds and plants for food, trade, and crafts. Even today, descendants use plants like milkweed and willow for baskets, medicines, and string.

Meadow plants were very important to these tribes. For thousands of years, Native Americans used controlled fires to keep the valley meadows open. This prevented forests from growing too much. These fires helped grasses and shrubs grow, which were important for food. They also created more space for large animals like deer. Early white visitors didn't realize that the meadows were created by people. They thought the valley was purely natural.

The name Hetch Hetchy might come from the Miwok word hatchhatchie. This means "edible grasses" or "magpie." It's thought the edible grass was blue dicks. Chief Tenaya of the Yosemite Valley's Ahwaneechee tribe said Hetch Hetchy meant "Valley of the Two Trees." This referred to two yellow pines that once stood there. Miwok names are still used for places like Tueeulala Fall and Kolana Rock.

Unlike Yosemite Valley, Hetch Hetchy was only lived in during certain seasons. This was likely because its narrow outlet caused flooding when a lot of snow melted.

Building the Dam

In 1906, a huge earthquake and fire destroyed much of San Francisco. This showed that the city's water system was not good enough. San Francisco asked the U.S. government for the right to use Hetch Hetchy's water. In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt's Secretary of the Interior, James R. Garfield, gave San Francisco permission.

This started a seven-year fight with environmental groups like the Sierra Club, led by John Muir. Muir famously said, "Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people's cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man."

People who supported the dam said Hetch Hetchy was perfect for a reservoir. They said it had clean water, no private property, and steep sides that would hold a lot of water. They also said the valley was not unique and would look even better with a lake. Muir, however, warned that the lake would leave an ugly "bathtub ring" on the canyon walls when water levels dropped.

Because the valley was inside Yosemite National Park, Congress had to approve the project. In 1913, Congress passed and President Woodrow Wilson signed the Raker Act. This law allowed the valley to be flooded. It also said that the power and water from the river could only be used for public benefit. However, the city later sold some of the power to a private company, Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E). This led to many legal arguments over the years.

Work on the Hetch Hetchy Project began in 1914. A 68 mi (109 km) railroad was built to bring materials to the dam site. Construction of O'Shaughnessy Dam started in 1919 and finished in 1923. The reservoir filled with water in May 1923. The dam was first 227 feet (69 m) high and was made taller in 1938 to 312 feet (95 m). On October 28, 1934, San Francisco celebrated the arrival of the first Hetch Hetchy water in the city.

Several powerhouses were built as part of the project. The Early Intake Powerhouse started in 1920. The first Moccasin Powerhouse in Moccasin opened in 1925. Over the years, new powerhouses were built and old ones were replaced or updated.

The Hetch Hetchy Project Today

|

Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct

|

|

|---|---|

| Begins | Tuolumne River 37°51′09″N 119°59′30″W / 37.852425°N 119.991572°W |

| Ends | Crystal Springs Reservoir 37°29′01″N 122°18′59″W / 37.483508°N 122.316306°W |

| Maintained by | San Francisco Public Utilities Commission |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 167 mi (269 km) |

| Capacity | 366 cu ft/s (10.4 m3/s) |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1914 |

| Opened | 24 October 1934 |

| References | |

| . Note that map above only shows Bay Area portion of aqueduct. |

|

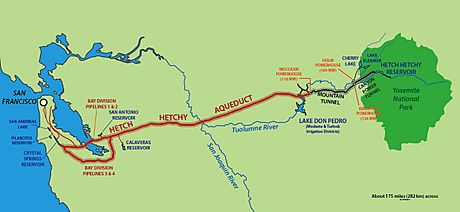

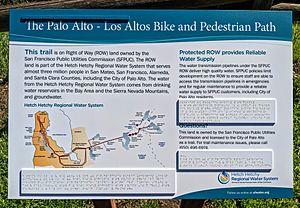

Hetch Hetchy Valley is the main water source for San Francisco and other cities in the San Francisco Bay Area. The dam, reservoir, and a system of aqueducts, tunnels, and hydroelectric plants make up the Hetch Hetchy Project. This system provides 80% of the water for 2.6 million people. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission operates the project. The city pays $30,000 a year to use Hetch Hetchy, as it's on federal land. The aqueduct delivers about 265,000 acre⋅ft (327,000 dam3) of water each year. This is about 31,900,000 cu ft (900,000 m3) per day, to residents in San Francisco and nearby counties.

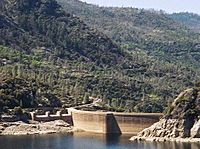

The O'Shaughnessy Dam is 910 feet (280 m) long. It spans the narrowest part of the valley. The dam is made of 675,000 cu yd (516,000 m3) of concrete. The Hetch Hetchy Reservoir holds 360,400 acre⋅ft (0.4445 km3) of water. It has a maximum area of 1,972 acres (798 ha) and a depth of 306 feet (93 m).

Water from the reservoir flows through tunnels to powerhouses. These powerhouses, like Kirkwood and Moccasin, generate electricity. Another hydroelectric system, including Cherry Lake and Lake Eleanor, also adds to the power. The entire system produces about 1.7 billion kilowatt hours of electricity each year. This is enough to meet 20% of San Francisco's electricity needs.

After the powerhouses, the water flows into the 167 mi (269 km) Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct. This aqueduct crosses the Central Valley. Near Fremont, it splits into four large pipelines. These pipelines cross the Hayward fault. Two pipelines cross the San Francisco Bay, while the other two run south of the bay. In the Bay Area, Hetch Hetchy water is stored in local reservoirs like Calaveras Reservoir and Crystal Springs Reservoir.

Hetch Hetchy water is some of the cleanest city water in the United States. San Francisco is one of only six U.S. cities that doesn't have to filter its tap water. The water is cleaned using ozone and UV light. The water is so clean because the area it comes from is mostly bare granite. This means the rivers feeding the reservoir have very little dirt or nutrients. The watershed is also strictly protected. Swimming and boating are not allowed in the reservoir, which helps keep the water clean. Fishing is allowed in the reservoir and the rivers that feed it.

In 2018, the Department of the Interior thought about allowing some boating on the reservoir. A group called Restore Hetch Hetchy supported this idea. They argued that San Francisco has benefited from the water for a long time, but the American people haven't been able to fully enjoy the valley.

Should Hetch Hetchy Be Restored?

Arguments for Restoration

The debate over Hetch Hetchy Valley continues today. Some people want to keep the dam and reservoir. Others want to drain the reservoir and return Hetch Hetchy Valley to its natural state. Those who want to remove the dam say that San Francisco has broken the rules of the Raker Act. This act said that power and water from Hetch Hetchy could not be sold to private companies. However, San Francisco sells some of the hydroelectric power to a private company, Pacific Gas & Electric. The city said this was a temporary solution, but it was never changed.

Groups like the Sierra Club and Restore Hetch Hetchy believe that draining the reservoir would allow people to enjoy the valley again. They say this is a right for the American people, especially since the reservoir is inside a national park. They know that managing wildlife and tourism would be important to protect the ecosystem. It might take many years for the valley to return to its natural conditions.

In 1987, Don Hodel, who was the Secretary of the Interior under President Ronald Reagan, supported studying the idea of tearing down the dam. The National Park Service studied it. They found that two years after draining the valley, grasses would cover most of the floor. Within 10 years, trees would start to grow. After 50 years, most of the valley would be covered in plants, except for rocky areas. If left alone, a forest would grow instead of the original meadow. However, the study also said that with careful management, the valley could look much like it did before the reservoir.

The dam might not need to be completely removed. A hole could be cut through its base to drain the water and let the Tuolumne River flow naturally again. Most of the dam could stay as a monument. The water storage from Hetch Hetchy could be moved to New Don Pedro Dam further down the Tuolumne River by making that dam 30 ft (9.1 m) taller. This would also increase power generation there. Removing O'Shaughnessy Dam would not require a lot of costly sediment removal. This is because the Tuolumne River water is very clean. In 90 years, only about 2 in (5.1 cm) of sediment had built up in the reservoir. A 2019 study said that draining the reservoir and adding tourism facilities could bring in up to $178 million per year.

Arguments Against Restoration

Those against removing the dam say it would mean losing a valuable source of clean, renewable hydroelectric power. Even if some power could still be generated, it would be much less. The missing power would likely have to come from fossil fuels, which cause pollution. Removing the dam would also be very expensive, costing at least $3–10 billion. Transporting the demolished materials away from the dam site would be very difficult.

Most importantly, San Francisco would lose its source of high-quality mountain water. The city would have to rely on lower-quality water from other reservoirs. This would require expensive filtering and changes to the water system.

Some people, like Carl Pope from the Sierra Club, thought that Don Hodel's idea to study dam removal was political. They thought it was meant to divide environmental groups. Dianne Feinstein, who was the mayor of San Francisco at the time, said in 1987, "All this is for an expanded campground? It's dumb, dumb, dumb." Hodel still supports restoring Hetch Hetchy Valley, while Feinstein is still against it.

Opponents of dam removal also point out that the flooding of Hetch Hetchy Valley has kept crowds away. Hetch Hetchy is still the least visited area of Yosemite National Park. Some describe Yosemite Valley as "so crammed that it looks more like a ripstop ghetto than the site of a nature experience."

In November 2012, San Francisco voters rejected a proposal to study draining and restoring the valley. The study would have cost $8 million and looked for ways to replace the water storage and power generation.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |