Mule deer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mule deer |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male (buck) near Elk Creek, Oregon | |

|

|

| Female (doe) near Swall Meadows, California | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Genus: | Odocoileus |

| Species: |

O. hemionus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Odocoileus hemionus Rafinesque, 1817

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

10, but some disputed (see text) |

|

|

|

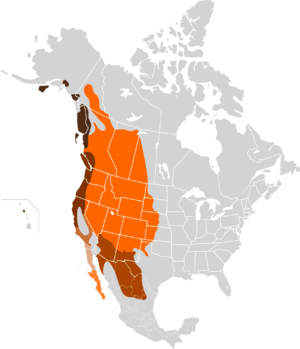

| Distribution map of subspecies:

Sitka black-tailed deer (O. h. sitkensis) Columbian black-tailed deer (O. h. columbianus) California mule deer (O. h. californicus) southern mule deer (O. h. fuliginatus) peninsular mule deer (O. h. peninsulae) desert mule deer (O. h. eremicus) Rocky Mountain mule deer (O. h. hemionus) |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) is a type of deer that lives in western North America. It gets its name because its ears are large, like those of a mule. There are two main groups of mule deer: the true mule deer and the black-tailed deer.

Unlike the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), which lives across most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains, mule deer are found mainly in the western Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, the southwest United States, and along the west coast. Mule deer have also been brought to Argentina and Kauai, Hawaii.

Contents

Types of Mule Deer

Mule deer are split into two main groups: the mule deer (the main group) and the black-tailed deer. Even though these groups are sometimes seen as separate species, they can mate and have babies together. Because of this, most experts now consider them the same species. Scientists believe that mule deer actually evolved from black-tailed deer.

Mule Deer Subspecies

There are 10 recognized types, or subspecies, of mule deer. Here are some of them:

- Mule deer group:

- O. h. californicus – California mule deer. These deer live in much of California, especially in the central and southern parts. You can find them in places like Sequoia National Park and the Sierra Nevada mountains. They also live in parts of western Nevada.

- O. h. cerrosensis – Cedros or Cerros Island mule deer. This subspecies only lives on Cedros Island, off the coast of Baja California in Mexico.

- O. h. eremicus – Desert or burro mule deer. These deer are found in hot, dry areas like the Lower Colorado River Valley, southern California, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico. They also live in parts of Mexico, including Sonora.

- O. h. fuliginatus – Southern mule deer. You can find these deer in Southern California, near cities like Los Angeles and San Diego. They also live along the U.S.-Mexico border and into the northern part of the Baja California peninsula.

- O. h. hemionus – Rocky Mountain mule deer. This is a common type found across western and central North America, from Colorado all the way north to Yukon and the Northwest Territories in Canada.

- O. h. inyoensis – Inyo mule deer. These deer live in the Sierra Nevada mountains and Yosemite National Park in central California. They can be seen as far south as Death Valley National Park.

- O. h. peninsulae – Baja or Peninsular mule deer. This subspecies lives in most of Baja California Sur, Mexico.

- O. h. sheldoni – Tiburón Island mule deer. This deer is only found on Tiburón Island, Mexico, which is in the Gulf of California.

- Black-tailed deer group:

- O. h. columbianus – Columbian black-tailed deer. These deer live in the rainy coastal forests of the Pacific Northwest and Northern California, stretching up to Vancouver, BC.

- O. h. sitkensis – Sitka black-tailed deer. Named after Sitka, Alaska, these deer live in similar rainforests as the Columbian subspecies, but further north. You can find them from central British Columbia up through Southeast Alaska, including places like the Tongass National Forest.

What Mule Deer Look Like

Mule deer have a few key differences from white-tailed deer. Their ears are much larger, their tails have a black tip, and their antlers grow differently. Mule deer antlers "fork" as they grow, meaning they split into two branches, unlike white-tailed deer antlers which grow from a single main beam.

Every spring, male deer (bucks) shed their old antlers, usually in mid-February. New antlers start growing almost right away.

Mule deer can run fast, but they are also known for a special jump called "stotting" or "pronking." When they stot, all four of their feet land on the ground at the same time.

Mule deer are generally larger than other deer species in their family. They stand about 80 to 106 centimeters (31 to 42 inches) tall at the shoulders. Their body length, from nose to tail, is about 1.2 to 2.1 meters (4 to 7 feet). Their tail itself can be 11.6 to 23 centimeters (4.6 to 9.1 inches) long.

Adult male deer (bucks) usually weigh between 55 and 150 kilograms (121 to 331 pounds), with an average of about 92 kilograms (203 pounds). Some very large bucks can weigh up to 210 kilograms (460 pounds). Female deer (does) are smaller, typically weighing 43 to 90 kilograms (95 to 198 pounds), with an average of about 68 kilograms (150 pounds).

One exception to their size is the Sitka deer subspecies (O. h. sitkensis). These deer are noticeably smaller than other mule deer. Males average about 54.5 kilograms (120 pounds), and females average about 36 kilograms (79 pounds).

Life Cycle and Behavior

The breeding season for mule deer, called the "rut," usually starts in the fall. During this time, female deer (does) are ready to mate for a few days. Male deer (bucks) become more aggressive and compete to find mates. A female deer might mate with more than one buck. If she doesn't get pregnant, she might be ready to mate again within a month.

Pregnancy lasts about 190 to 200 days. Fawns (baby deer) are born in the spring. About half of the fawns survive after birth. Fawns stay with their mothers through the summer and stop drinking milk in the fall, after about 60 to 75 days. Female mule deer usually give birth to two fawns, but if it's their first time, they often have just one.

A buck's antlers fall off during the winter. They then grow back in time for the next breeding season. The amount of daylight controls this yearly cycle of antler growth.

The size of mule deer groups changes with the seasons. Groups are smallest when fawns are born (June and July). They are largest in the winter (February and March), when females are pregnant.

Besides humans, the main predators of mule deer are coyotes, wolves, and cougars (also called mountain lions). Other animals like bobcats, Canada lynx, wolverines, American black bears, and grizzly bears might hunt adult deer, but they usually only attack fawns or sick deer. Bears and smaller meat-eaters often eat deer that have already died naturally. They usually don't threaten strong, healthy mule deer.

What Mule Deer Eat

Mule deer eat many different kinds of plants. In studies, they were found to eat 788 different plant species! What they eat changes a lot depending on the season, where they live, and how high up they are.

Here's a general idea of what Rocky Mountain mule deer eat:

| Season | Shrubs and trees | Forbs (flowering plants) | Grasses and grass-like plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | 74% | 15% | 11% |

| Spring | 49% | 25% | 26% |

| Summer | 49% | 46% | 3% |

| Fall | 60% | 30% | 9% |

Mule deer are "intermediate feeders." This means they mostly eat leaves and twigs from shrubs and trees (called "browsing"). But they also eat flowering plants (forbs), a small amount of grass, and fruits like beans, nuts (including acorns), and berries when they can find them.

Mule deer can also get used to eating farm crops and plants in gardens. In the Sierra Nevada mountains, mule deer rely on a type of lichen called Bryoria fremontii for food in winter.

Some common plants mule deer eat include:

- Trees and shrubs: Big sagebrush, curlleaf mountain mahogany, Mexican cliffrose, quaking aspen, antelope bitterbrush, Gambel oak, and skunkbush sumac.

- Flowering plants (forbs): Western yarrow, pussytoes, fringed sagebrush, aster species, milkvetch, arrowleaf balsamroot, thistle, fleabane, geranium, prickly lettuce, lupine, alfalfa, penstemon, phlox, knotweed, cinquefoil, dandelion, western salsify, clover, and American vetch.

- Grasses and grass-like plants: Wheatgrasses, bluebunch wheatgrass, cheatgrass, sedge, Idaho fescue, muttongrass, and Kentucky bluegrass.

Mule deer also eat other plants like ricegrass, gramagrass, needlegrass, bearberry, bitter cherry, black oak, ceanothus, cedar, cottonwood, elderberry, mesquite, pine, rabbitbrush, serviceberry, snowberry, sunflower, and wild oats. They also enjoy wild mushrooms, especially in late summer and fall. Mushrooms give them moisture, protein, and important minerals.

Sometimes, people try to feed mule deer during harsh winters to help them. However, wildlife experts usually advise against this. Feeding deer can cause problems like spreading diseases (such as tuberculosis and chronic wasting disease) because many deer gather in one spot. It can also change their natural migration paths and lead to too many deer in one area, which can damage their habitat. If feeding is done, it must be very carefully planned and started early in the winter.

Mule deer often live alone or in small groups. About 35% to 64% of them are solitary. Small groups usually have 5 or fewer deer. The average group size is about three to five deer.

Nutrition

Mule deer are ruminants. This means they have a special stomach system that helps them digest tough plant material. They ferment their food before it's fully digested. Deer that eat foods high in fiber need less food overall than those that eat foods high in starch. They also spend more time chewing their cud (ruminating) when they eat high-fiber foods. This helps them get more nutrients from their food.

Because some mule deer travel long distances, they find different kinds of food throughout the year. The food they eat in summer has more easy-to-digest parts like proteins and starches than the food they eat in winter.

Mule deer store fat in their bodies, and the amount changes throughout the year. They have the most fat stored in October, which they use up during the winter. By March, their fat levels are at their lowest.

Migration

Mule deer often travel from lower areas where they spend the winter to higher mountain areas for the summer. Not all mule deer migrate, but some travel very long distances between their summer and winter homes. Researchers found one mule deer migration in Wyoming that was 150 miles long! Many U.S. states keep track of these deer migrations.

Mule deer migrate in the fall to escape harsh winter weather, especially deep snow that covers their food. In the spring, they follow the new plant growth northward. There's evidence that mule deer remember their migration paths and use the same ones year after year, even if food sources have changed. This shows how important these paths are for their survival.

Migration Risks

Mule deer face several dangers during their migrations, including climate change and human activities. Climate change can affect when plants grow, which might make old migration paths less useful for deer.

Human activities also impact mule deer. Things like taking natural resources (like oil and gas), building highways, putting up fences, and developing cities all hurt mule deer populations. These activities can damage their homes and break up their migration routes. For example, natural gas drilling can make deer avoid areas they used to migrate through. Highways can cause deer to get hit by cars, and they can also block deer from moving freely. Fences can also act as barriers, changing how deer move.

As cities grow, they replace deer habitats with houses and increase human activity. This has led to a decline in mule deer numbers, especially in places like Colorado, where the human population has grown a lot since 1980.

Protecting Mule Deer Migrations

Protecting Migration Paths

It's very important to protect the paths mule deer use for migration to keep their populations healthy. One thing everyone can do is help slow down climate change by using cleaner energy and reducing waste. Also, wildlife managers and researchers can study the risks mentioned above and take steps to lessen their impact on mule deer. These efforts will help not only deer but many other wildlife species too.

Highways

To help protect deer from getting hit on roads, special high fences with escape routes can be installed. These fences keep deer off the road, preventing accidents. For busy highways that cross migration routes, managers have built natural-looking overpasses and underpasses. These allow animals like mule deer to cross safely without going onto the road.

Natural Resource Extraction

To reduce the impact of drilling and mining, rules can be put in place about when active drilling and heavy traffic can happen. Careful planning can also protect important deer habitats. Barriers can be used to reduce noise, light, and activity at these sites.

Urban Development

Growing cities affect mule deer migrations and can even stop different groups of deer from mixing their genes. One clear solution is to avoid building houses in important mule deer habitats. However, some deer living near cities have gotten used to humans and found resources like food and water there. Instead of migrating through urban areas, some deer stay close to these developments to find food and avoid obstacles. Property owners can help by planting deer-resistant plants, using noise-makers to scare deer away, and most importantly, by not feeding deer.

Images for kids

-

Male Rocky Mountain mule deer (O. h. hemionus) in Zion National Park

-

Male O. h. hemionus near Leavenworth, Washington

-

Female Columbian black-tailed deer (O. h. columbianus) in Olympic National Park

See also

In Spanish: Ciervo mulo para niños

In Spanish: Ciervo mulo para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |