Olympic National Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Olympic National Park |

|

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category II (National Park)

|

|

Cedar Creek and Abbey Island from Ruby Beach

|

|

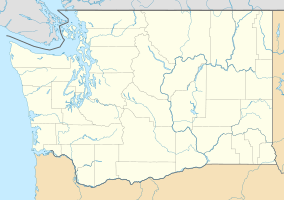

| Location | Jefferson, Clallam, Mason, and Grays Harbor counties, Washington, United States |

| Nearest city | Port Angeles |

| Area | 922,650 acres (3,733.8 km2) |

| Established | June 29, 1938 |

| Visitors | 2,432,972 (in 2022) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Olympic National Park |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Natural: vii, ix |

| Inscription | 1981 (5th Session) |

Olympic National Park is a special place in the United States! It's a national park found in the state of Washington, on a big piece of land called the Olympic Peninsula. This amazing park has four main areas: the Pacific coastline, high alpine mountains, a super wet temperate rainforest on the west side, and drier forests on the east side.

Inside the park, you'll find three different natural environments, called ecosystems. These include forests and meadows high up in the mountains, thick temperate forests, and the wild Pacific coast.

President Theodore Roosevelt first made this area a national monument in 1909. It was called Mount Olympus National Monument. Later, in 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the U.S. Congress changed it into a full national park.

Olympic National Park is so important that UNESCO named it an International Biosphere Reserve in 1976. Then, in 1981, it became a World Heritage Site. This means it's a place of special natural value to the whole world. In 1988, most of the park (about 1,370 square miles or 3,548 square kilometers) was made into the Olympic Wilderness. This wilderness area was later renamed the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness in 2017, honoring a former governor and senator who helped create it. It's the largest wilderness area in Washington state!

Contents

Why Was Olympic National Park Created?

Olympic National Park was created for several important reasons. Its main goal is to protect a huge wild area. This area has some of the best examples of old-growth forests in the entire United States. These forests are filled with giant Sitka Spruce, Western Hemlock, Coast Douglas-fir, and Western redcedar trees.

The park also protects large groups of native Roosevelt elk and other wild animals. It makes sure they have a safe place to live, especially in winter. Plus, the park helps people enjoy this beautiful mountain area. It has many glaciers and snowy peaks. It also includes the green forests around them and a lovely part of the Washington coast.

Exploring the Park's Natural History

The Rugged Coastline

The coastal part of Olympic National Park is a wild, sandy beach. It also has a strip of forest right next to it. This section is about 60 miles (97 km) long but only a few miles wide. Native communities, like the Hoh people and the Quileute people, live near the mouths of the Hoh River and Quileute River.

The beach has long, wild stretches that are 10 to 20 miles (16 to 32 km) long. Some beaches are mostly sand, while others are covered with heavy rocks and huge boulders. Walking here can be tricky because of thick bushes, slippery ground, changing tides, and misty rainforest weather. Even though it's easier to reach than the park's inner mountains, most people only go for short day hikes.

A popular part of the coast is the 9-mile (14 km) Ozette Loop. The park manages how many people visit this area to protect it. From the start of the trail at Ozette Lake, you walk about 3 miles (5 km) on a boardwalk through a ancient cedar swamp. When you reach the ocean, you walk another 3 miles along the beach. There are also trails on the headlands for when the tide is high. The Makah from Neah Bay have traditionally used this area. The last 3 miles of the loop also have a boardwalk, making it easier to explore.

Right next to the sand, there are thick groups of trees. This means you'll see large pieces of wood from fallen trees on the beach. The Hoh River, which is mostly untouched, brings a lot of natural wood and other debris north to the beaches. Even today, these piles of driftwood are a big part of the landscape. They show how the beach looked a long time ago. Sometimes, this driftwood comes from far away, like the Columbia River.

The smaller coastal part of the park is separate from the larger inland part. President Franklin D. Roosevelt originally wanted to connect them with a continuous strip of parkland.

The park is also known for its unique turbidites. These are rocks or sediments that travel into the ocean as suspended particles in water. Over time, they settle and compact, creating layers on the ocean floor. The park has very exposed turbidites with white calcite veins. The park also has special mélanges, which locals call 'smell rocks' because they have a strong petroleum smell. Mélanges are huge individual rocks, sometimes as big as a house, that are even shown on maps.

Mountains and Glaciers

In the middle of Olympic National Park, you'll find the Olympic Mountains. Their sides and ridges are covered with huge, ancient glaciers. These mountains were formed when the Juan De Fuca Plate pushed under another plate, causing the land to rise. The rocks here are a mix of basalt and ocean sediments.

The western part of the mountains is dominated by Mount Olympus, which is 7,965 feet (2,428 meters) tall. Mount Olympus gets a lot of snow. Because of this, it has more glaciers than any other non-volcanic mountain in the lower 48 United States, outside of the North Cascades. It has several glaciers, and the biggest one is Hoh Glacier, which is about 3.06 miles (4.93 km) long.

Looking east, the mountains become much drier. This is because the western mountains block the rain, creating a rain shadow. Here, you'll find many high peaks and rocky ridges. The tallest peak in this area is Mount Deception, at 7,788 feet (2,374 meters).

The Wet Temperate Rainforest

The western side of the park is covered by temperate rainforests. These include the Hoh Rainforest and Quinault Rainforest. They get over 12 feet (3.7 meters) of rain each year! This makes them one of the wettest places in the continental United States.

Unlike tropical rainforests and most other temperate rainforests, the ones in the Pacific Northwest are mostly made up of coniferous trees. These include Sitka Spruce, Western Hemlock, Coast Douglas-fir, and Western redcedar. Soft mosses cover the bark of these trees and even hang down from their branches like green, wet ribbons.

Valleys on the eastern side of the park also have important old-growth forests. However, the weather there is much drier. You won't find Sitka Spruce trees, and the trees are generally a bit smaller. The plants growing on the forest floor are also less dense and different. Just northeast of the park is a rainshadow area where it only rains about 17 inches (43 cm) a year.

Animals and Plants of the Park

Because the park is on an isolated peninsula and has a high mountain range separating it from the land to the south, many unique plants and animals have developed here. These are called endemic species, meaning they are found nowhere else. Examples include the Olympic Marmot, Piper's bellflower, and Flett's violet.

The park is also home to many species, like the Roosevelt elk, that only live along the Pacific Northwest coast. Scientists study these unique species to learn how plants and animals change over time. The park has many black bears and black-tailed deer. It also has a good number of cougars, about 150 of them.

Unfortunately, Mountain goats were accidentally brought into the park in the 1920s. They have caused a lot of damage to the native plants. The park service has plans to control the goat population. The park also has about 366,000 acres (1,481 square kilometers) of old-growth forests.

Forest fires are rare in the park's western rainforests. However, in the summer of 2015, a very dry spring and low snow from winter caused a rare rainforest fire.

- Ecological zones - glaciated mountains, subalpine forests and meadows, temperate rainforests, and coastline

-

The summit of Mount Olympus from the Blue Glacier

-

Subalpine fir in a meadow on Hurricane Ridge

Park Climate

The climate in Olympic National Park changes depending on where you are. The western part has a temperate oceanic climate, which means it's mild and wet. The eastern part has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate, with warm, dry summers.

| Climate data for Elwha Ranger Station, Washington, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1942–2017 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 64 (18) |

67 (19) |

70 (21) |

80 (27) |

87 (31) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

97 (36) |

91 (33) |

76 (24) |

70 (21) |

65 (18) |

97 (36) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 51.1 (10.6) |

51.9 (11.1) |

60.1 (15.6) |

70.6 (21.4) |

77.8 (25.4) |

82.6 (28.1) |

87.6 (30.9) |

87.0 (30.6) |

79.5 (26.4) |

67.1 (19.5) |

55.4 (13.0) |

49.8 (9.9) |

90.7 (32.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 41.1 (5.1) |

43.8 (6.6) |

49.7 (9.8) |

56.3 (13.5) |

63.4 (17.4) |

67.2 (19.6) |

73.6 (23.1) |

74.5 (23.6) |

68.1 (20.1) |

55.5 (13.1) |

45.6 (7.6) |

40.7 (4.8) |

56.6 (13.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.0 (2.8) |

38.3 (3.5) |

42.3 (5.7) |

47.1 (8.4) |

53.3 (11.8) |

57.2 (14.0) |

62.2 (16.8) |

63.0 (17.2) |

58.1 (14.5) |

48.5 (9.2) |

40.8 (4.9) |

36.7 (2.6) |

48.7 (9.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 32.8 (0.4) |

32.8 (0.4) |

34.9 (1.6) |

37.8 (3.2) |

43.2 (6.2) |

47.2 (8.4) |

50.7 (10.4) |

51.6 (10.9) |

48.0 (8.9) |

41.5 (5.3) |

36.1 (2.3) |

32.7 (0.4) |

40.8 (4.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 24.3 (−4.3) |

24.5 (−4.2) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

35.3 (1.8) |

40.4 (4.7) |

44.2 (6.8) |

44.9 (7.2) |

40.6 (4.8) |

32.6 (0.3) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 2 (−17) |

8 (−13) |

15 (−9) |

26 (−3) |

29 (−2) |

32 (0) |

31 (−1) |

36 (2) |

32 (0) |

21 (−6) |

10 (−12) |

8 (−13) |

2 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 8.87 (225) |

6.14 (156) |

6.94 (176) |

3.28 (83) |

1.91 (49) |

1.39 (35) |

0.74 (19) |

1.14 (29) |

1.63 (41) |

5.85 (149) |

10.06 (256) |

9.92 (252) |

57.87 (1,470) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.1 (0.25) |

2.0 (5.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.8 | 15.4 | 18.2 | 13.8 | 11.5 | 9.5 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 8.0 | 15.0 | 18.6 | 18.4 | 155.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Hoh Rainforest Visitor Center (elevation: 745 ft / 227 m), 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 44.7 (7.1) |

47.9 (8.8) |

51.4 (10.8) |

55.8 (13.2) |

61.8 (16.6) |

65.4 (18.6) |

70.8 (21.6) |

72.2 (22.3) |

67.4 (19.7) |

58.8 (14.9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

43.9 (6.6) |

57.5 (14.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 39.8 (4.3) |

41.2 (5.1) |

43.5 (6.4) |

46.8 (8.2) |

52.1 (11.2) |

56.1 (13.4) |

60.5 (15.8) |

61.3 (16.3) |

57.5 (14.2) |

50.8 (10.4) |

43.2 (6.2) |

38.8 (3.8) |

49.3 (9.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 34.8 (1.6) |

34.4 (1.3) |

35.6 (2.0) |

37.8 (3.2) |

42.4 (5.8) |

46.8 (8.2) |

50.1 (10.1) |

50.5 (10.3) |

47.6 (8.7) |

42.7 (5.9) |

37.6 (3.1) |

33.8 (1.0) |

41.2 (5.1) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 20.59 (523) |

14.45 (367) |

14.78 (375) |

10.60 (269) |

6.39 (162) |

4.68 (119) |

2.16 (55) |

2.76 (70) |

4.15 (105) |

13.11 (333) |

22.55 (573) |

19.07 (484) |

135.29 (3,436) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.1 | 76.0 | 76.8 | 74.1 | 71.9 | 73.9 | 68.8 | 69.9 | 69.0 | 74.2 | 83.0 | 83.1 | 75.5 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 35.7 (2.1) |

34.2 (1.2) |

36.7 (2.6) |

39.0 (3.9) |

43.3 (6.3) |

47.9 (8.8) |

50.2 (10.1) |

51.4 (10.8) |

47.4 (8.6) |

42.9 (6.1) |

38.4 (3.6) |

34.1 (1.2) |

41.8 (5.4) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group | |||||||||||||

Human History in the Park

Before European settlers arrived, Native Americans lived on the Olympic Peninsula. They used the land for fishing and hunting. However, new studies show that tribes used the mountain meadows much more than previously thought. Many Native American cultures in the Pacific Northwest were greatly affected by European diseases before settlers arrived. This means that what early explorers saw was a much smaller version of the native cultures. Today, many cultural sites and important artifacts have been found in the Olympic mountains.

When settlers started coming, the logging industry grew quickly in the Pacific Northwest. People began cutting down many trees in the late 1800s and early 1900s. But in the 1920s, people started to protest against logging. They saw how the hillsides were being completely cleared of trees. At the same time, more people became interested in the outdoors. With cars becoming popular, people could visit places like the Olympic Peninsula more easily.

The idea of making a national park here started with explorers like Lieutenant Joseph P. O'Neil and Judge James Wickersham in the 1890s. They met in the Olympic wilderness and decided to work together to protect the area. In 1897, President Grover Cleveland created the Olympic Forest Reserve, which became Olympic National Forest in 1907.

After attempts to protect the area more failed in the Washington State Legislature, President Theodore Roosevelt created Mount Olympus National Monument in 1909. His main goal was to protect the areas where Roosevelt elk herds gave birth and spent their summers.

People wanted even more protection for the area. So, in 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a bill creating the national park. The Civilian Conservation Corps built the park's headquarters in 1939. This building is now on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1953, the park grew by 47,753 acres (19,325 hectares). This addition included the Pacific coastline between the Queets and Hoh rivers, and parts of the Queets and Bogachiel valleys.

Even after it became a national park, some illegal logging continued. There are still discussions today about the valuable timber in the area. Logging still happens on the Olympic Peninsula, but not inside the park. The Olympic Wilderness, a special protected area, was created in 1988. It covers 877,000 acres (354,910 hectares) within Olympic National Park. In 2017, it was renamed the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness to honor Senator Daniel J. Evans, who helped create it. A plan to make the wilderness area even bigger in 2022 was not successful.

Animals of Olympic National Park

Many animals live in Olympic National Park! You might see chipmunks, squirrels, skunks, and six different kinds of bats. Other animals include weasels, coyotes, muskrats, fishers, river otters, beavers, red foxes, mountain goats, martens, bobcats, black bears, Canadian lynxes, moles, snowshoe hares, and shrews. The park also has a good number of cougars.

In the waters near the park, you might spot whales, dolphins, sea lions, seals, and sea otters. Many birds also fly in the park. These include Winter wrens, Canada jays, Hammond's flycatchers, Wilson's warblers, Blue Grouses, Pine siskins, ravens, and spotted owls. You might also see Red-breasted nuthatches, Golden-crowned kinglets, Chestnut-backed chickadees, Swainson's thrushes, Red crossbills, Hermit thrushes, Olive-sided flycatchers, bald eagles, Western tanagers, Northern pygmy owls, Townsend's warblers, Townsend's solitaires, Vaux's swifts, band-tailed pigeons, and evening grosbeaks.

Fun Things to Do in the Park

There are a few roads in Olympic National Park, but none go deep into the park's center. The park has many hiking trails. However, because the park is so big and wild, it usually takes more than a weekend to reach the high mountains in the middle. The rainforest views, with their wild plants and many shades of green, are worth the chance of rain. But July, August, and September often have long dry periods.

A unique thing to do in Olympic National Park is backpacking along the beach. The coastline in the park is long enough for trips that last several days. You can spend the whole day walking along the beach. While this sounds easier than climbing a mountain, you must be careful of the tide. In the narrowest parts of the beaches, high tide can reach the cliffs, blocking your way. You might need to climb over some rocky points using muddy, steep trails and fixed ropes.

In winter, the viewpoint called Hurricane Ridge offers many winter sports. The Hurricane Ridge Winter Sports Club runs a non-profit ski area. It offers ski lessons, rentals, and affordable lift tickets. This small ski area has two rope tows and one poma lift. A lot of backcountry terrain is available for skiers and snowboarders when Hurricane Ridge Road is open. Currently, the road is open Friday through Sunday, if the weather allows. A community group is working to open the road seven days a week in winter.

You can go rafting on both the Elwha and Hoh Rivers. Boating is popular on Ozette Lake, Lake Crescent, and Lake Quinault. Fishing is allowed in the Ozette River, Queets River (below Tshletshy Creek), Hoh River, Quinault River (below North Shore Quinault River Bridge), Quillayute River, and Dickey River. You don't need a fishing license to fish in the park. However, you are not allowed to fish for bull trout and Dolly Varden trout. If you catch them by accident, you must release them.

You can see amazing views of Olympic National Park from the Hurricane Ridge viewpoint. The road west from the Hurricane Ridge visitor center has picnic areas and trailheads. A paved trail called the Hurricane Hill trail is about 1.6 miles (2.6 km) long each way. It climbs about 700 feet (213 meters). It's common to find snow on the trails even in July. Several other dirt trails of different lengths and difficulty levels branch off the Hurricane Hill trail. The picnic areas are only open in the summer. They have restrooms, water, and paved access to picnic tables.

The Hurricane Ridge visitor center burned down on May 7, 2023. It was built in the 1950s and had a 3D map of the Olympics, a media center with nature documentaries, and a gift shop. There is no set date for when the center will be rebuilt. However, $80 million in federal money was set aside in late 2023 to rebuild the lodge and create a temporary visitor center.

Elwha River Restoration Project

The Elwha Ecosystem Restoration Project is one of the biggest projects to restore a natural environment in the history of the National Park Service. This project involved removing two dams from the Elwha River: the 210-foot (64-meter) Glines Canyon Dam and its reservoir, Lake Mills, and the 108-foot (33-meter) Elwha Dam and its reservoir, Lake Aldwell.

After the dams were removed, the park worked to replant trees and plants on the slopes and river bottoms. This helps stop erosion and speeds up the natural recovery of the area. The main goal of this project was to bring back anadromous fish, like Pacific Salmon and steelhead, to the Elwha River. For over 95 years, these fish could not reach the upper 65 miles (105 km) of river habitat because of the dams. The removal of the dams was finished in 2014.

See also

In Spanish: Parque nacional Olympic para niños

In Spanish: Parque nacional Olympic para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |