Maritime history of California facts for kids

The maritime history of California is all about how people have used ships and the Pacific Ocean along California's coast. This story can be split into different time periods. It starts with the Native American people, then moves to when Europeans first explored the area (1542-1769). After that came the Spanish colonial period (1769-1821), followed by the Mexican period (1821-1847), and finally, when California became a state of the United States (1847-today).

Throughout history, people in California have used many kinds of boats, from simple dugout canoes to large sailing ships and steamships. The ocean was also important for fishing, building ships, shipping goods during the California Gold Rush, creating busy ports, and even for naval ships and lighthouses.

Contents

- Native California's Amazing Boats

- Early European Explorers and Their Ships

- Spanish California's Maritime Life (1769-1821)

- Mexican California's Maritime Activities (1821-1846)

- U.S. California Naval Activity and the Gold Rush

- California Fisheries: Harvesting the Ocean

- California Naval Bases: Protecting the Coast

- California Shipbuilding: Building Ships for the Nation

- California Ports: Gateways to the World

- Ferry Service: Crossing the Waters

- Shipwrecks: Dangers at Sea

- Lighthouses: Guiding Ships Safely

- Images for kids

Native California's Amazing Boats

For thousands of years before Europeans arrived, Native American people lived along California's coast and on the Channel Islands. They were very skilled at building boats and using the ocean for travel, trade, and finding food.

Dugout Canoes: Boats from Trees

In northern California, near the huge redwood forests, some Native American tribes built big dugout canoes. They used these canoes for fishing, trading with other tribes, and even for fighting.

To make a dugout canoe, they would choose a large tree, often one that had already fallen. They used hand tools and fire to shape the log into a boat. They would start small fires on the wood, then put them out. This would char the wood, making it easier to scrape away with tools made from rock, shells, or animal horns. It took a lot of time and skill to make these canoes. A finished dugout canoe could weigh over 100 kilograms (220 pounds), so they were often just pulled up onto the beach. These strong canoes usually lasted for several years.

Tule Boats: Floating on Reeds

Native Americans also made boats from a plant called tule (also known as bulrushes). Tule grows in wet, marshy areas and has long, thin, green stems filled with spongy, airy tissue, which makes it float very well.

To build a tule boat, they would cut green tule and let it dry in the sun for a few days. Then, they would bundle the dried tule stalks together, often around a willow branch for extra strength. They could bend the bundles to create a raised front (prow) and back (stern) for the boat. These boats were usually about 3 to 4.5 meters (10 to 15 feet) long and could carry one to four people.

Tule boats could be built quickly, sometimes in less than a day by experienced builders. However, they didn't last very long, usually only a few weeks, before the tule would start to rot.

Many tribes around the San Francisco Bay area and in northern California used tule canoes. They were perfect for traveling in lakes, bays, and slow-moving rivers. People used them to get to their favorite spots for hunting ducks and geese, or for gathering salmon, acorns, seeds, berries, and shellfish like oysters. They also used them for fishing with nets, spears, or bone hooks.

Tomol Canoes: Sewn Plank Boats

Along the Santa Barbara Channel in Southern California, the Chumash people and Tongva people developed very advanced canoes called "tomols." These boats were so impressive that early European explorers were amazed by how strong and useful they were.

Tomols were built from planks of wood, often split from redwood or pine driftwood that washed ashore. The planks were shaped and then "sewn" together using strong fibers from the red milkweed plant. The gaps between the planks were sealed with a mixture of tar and pine pitch, like caulking. Building a tomol was a complex process, using over 20 pieces of shaped wood.

These canoes could carry 3 to 10 people and were propelled by oars. They were used for fishing and for trading between villages on the mainland and the Channel Islands. The Chumash and Tongva people were skilled fishermen, catching sardines and other fish with nets, harpoons, and bone hooks. They also traveled long distances, sometimes over 200 kilometers (130 miles), to trade for soapstone to make bowls and figures.

Early European Explorers and Their Ships

European explorers began to arrive in California in the 1500s, looking for new lands, riches, and a shorter route to Asia.

First Explorers: Cabrillo and Ulloa

In 1539, Francisco de Ulloa explored the Gulf of California, proving that Baja California was a peninsula, not an island. He sailed north along the west coast of Baja, but storms and illness forced his ships to turn back.

The first European to explore the coast of what is now California was Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542. Cabrillo was a skilled shipbuilder and explorer. He built three small sailing ships in Guatemala for his journey north: the San Salvador, the Victoria, and the San Miguel.

Cabrillo and his crew, a mix of Spanish and Native American sailors, set sail from Mexico in June 1542. The journey was slow and difficult due to strong winds and currents. After 103 days, they finally entered San Diego Bay in September 1542. They continued north, possibly reaching Point Reyes.

In November 1542, the fleet returned to Santa Catalina Island for winter repairs. Cabrillo was injured there and died in January 1543. His second-in-command, Bartolomé Ferrer, led the expedition back to Mexico. They didn't find any gold, advanced civilizations, or a shortcut to China, so Spain largely ignored California for over 200 years.

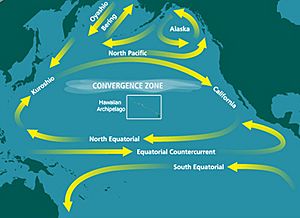

Manila Galleons and Trade Routes

In 1565, Spain started a very profitable trade route using large ships called Manila galleons. These ships carried silver from Mexico to the Philippines to trade for gold, silk, and spices from Asia.

The return trip was long and dangerous. Galleons would sail north from the Philippines to about 40 degrees latitude, then use the Westerlies winds to cross the Pacific. They would often arrive off the California coast near Cape Mendocino, then sail south to Acapulco, Mexico. This journey could take four to seven months.

These galleons were some of the largest ships of their time and carried valuable cargo. The Spanish Crown limited the number of ships, making the trade even more profitable. This trade continued for over 200 years, but the California coast was often foggy, and maps were poor, so ships usually stayed far offshore.

Drake and Other Explorers

The English explorer Francis Drake sailed along the California coast in 1579. He claimed the land for England, calling it "Nova Albion." His landing spot in Drakes Bay is now a National Historic Landmark.

Later, in 1587, another English explorer, Thomas Cavendish, captured a Manila galleon off Baja California. This led Spain to try and find a safe harbor in California for their galleons. However, in 1595, the galleon San Agustin was shipwrecked near Point Reyes during a storm. After this, Spain decided not to risk their valuable galleons for further exploration in California.

In 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno explored the California coastline from San Diego to Monterey Bay. He named San Diego Bay and held the first Christian church service in California there. He also made positive reports about Monterey Bay as a good place for ships to anchor. His basic maps were used by the Spanish for nearly 200 years.

Spanish California's Maritime Life (1769-1821)

By the mid-1700s, other European powers like Russia and Britain were showing interest in California. To prevent them from settling there, Spain decided to establish its own settlements in Alta California (present-day California) in 1769.

The Portolá Expedition

Spain planned a large expedition to settle Alta California, sending three ships by sea and two groups by land. Their goal was to meet at San Diego Bay. The sea journey was very difficult, with strong winds and many sailors getting sick with scurvy. Many died.

The land journeys were also tough, crossing dry and rugged terrain. When all the groups finally met in San Diego, only about half of the original 219 men had survived. Spain was trying to expand its empire with very little money or support.

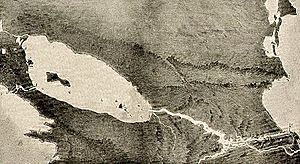

In July 1769, an expedition was sent to find Monterey, California. They didn't recognize Monterey Bay from old descriptions and traveled further north. On November 2, 1769, they discovered San Francisco Bay, one of the greatest natural harbors on the West Coast.

Life in the new Spanish settlements was hard, with food shortages and sickness. But in March 1770, a relief ship, the San Antonio, arrived with supplies, saving the settlement of Alta California.

Later, in 1775, Juan Bautista de Anza led a large group of soldiers, settlers, and friars from Mexico to the San Francisco Bay area. They brought horses and cattle, which became the start of the large ranches in California. This land route was later closed for over 40 years by Native American tribes, meaning most new settlers and supplies had to come by ship.

During this period, very few ships came to Alta California, averaging only about 2.5 ships per year. This was because Spain had strict rules against trading with foreign ships, and California had little to export.

Mexican California's Maritime Activities (1821-1846)

When Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the strict rules against foreign trade in California ended. California residents were eager to trade for new goods like glass, tools, and luxury items.

The Hide-and-Tallow Trade

California's main exports were cow hides (called California greenbacks), tallow (fat used for candles and soap), and cattle horns. These came from the large cattle ranches, or ranchos, where cattle roamed freely.

Ships from Boston, in the United States, were the main traders. They would sail about 17,000 to 18,000 miles (27,000-29,000 km) around Cape Horn to bring finished goods to California. The classic book Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana Jr. gives a good account of this trade.

From 1825 to 1848, the number of ships coming to California increased to about 25 per year. The main port for trade was Monterey, California, where customs duties (taxes on imported goods) were collected. These high taxes led to a lot of smuggling.

The United States had a strong seafaring tradition, especially in whaling. By the 1830s, the U.S. was the leading whaling nation, with many ships in the Pacific Ocean. These whaling ships often stopped in California or Hawaii for supplies.

The Mexican-American War and California

In 1846, the Mexican–American War began. The U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, with its sailing ships and Marines, played a key role in taking control of California.

On July 7, 1846, U.S. Marines and sailors landed in Monterey, California, the capital of Alta California, and captured the city without a fight. They raised the American flag. Soon after, other California towns like San Francisco, San Jose, San Diego, and Santa Barbara were also taken over peacefully.

A small revolt broke out in Los Angeles, but U.S. forces, including the newly formed "California Battalion" (made up of soldiers and volunteers), quickly re-occupied the city. The fighting in California ended in January 1847 with the Treaty of Cahuenga.

The California Gold Rush and Shipping

News of the California Gold Rush spread quickly after President James K. Polk officially announced it in December 1848. People from all over the world, especially young men, rushed to California hoping to find gold.

Many "forty-niners" (as they were called) traveled by sea. In 1849 alone, about 40,000 people came by sea. Hundreds of ships were abandoned in San Francisco Bay as their crews and passengers rushed to the gold fields.

Early maritime traffic brought passengers, food, lumber, and building supplies to California. Everything needed for daily life had to be imported from the East Coast or Europe. Sea transport was the only way to deliver large amounts of cargo.

San Francisco quickly became the main entry point for sea travelers and goods. Its population boomed, growing from about 200 people in 1846 to 36,000 by 1852.

Paddlewheel Steamers: The Fast Route

By 1849, shipping was changing from sail to steam power. Paddlewheel steamers, with large wheels on their sides or rear, became popular for faster travel.

The first paddle steamer to make a long ocean voyage was the SS Savannah in 1819. While it wasn't a commercial success at first, by 1848, steamships were regularly crossing the Atlantic.

In 1848, the U.S. Congress supported the Pacific Mail Steamship Company to set up regular mail, passenger, and cargo routes in the Pacific. The SS California, the first Pacific Mail paddle steamer, arrived in San Francisco in February 1849, packed with about 400 passengers.

The fastest way to California was by taking a paddle steamer to Panama, crossing the Isthmus of Panama by land, and then catching another steamer to California. This trip could take as little as 40 days, much faster than the 140-200 days it took by sailing ship around Cape Horn. Most of the gold found in California was shipped back East via this Panama route.

Sailing Ships: The Cheaper Way

Regular sailing ships were the cheapest and slowest way to travel. They were designed to carry large amounts of cargo with a small crew. Unless the cargo was needed quickly, sailing ships were used for almost all long-distance shipping.

Once in San Francisco, many crews would abandon their ships to join the Gold Rush. Ship owners often found little valuable cargo to ship back East, so ships sometimes returned empty, filled with rocks for balance. Many older ships were simply abandoned or sold cheaply. Some were even used as floating warehouses, stores, hotels, or prisons in San Francisco Bay.

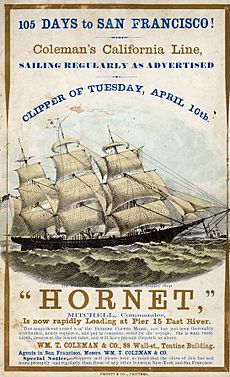

Clipper Ships: The Fastest Sails

Clipper ships, developed between 1840 and 1860, were some of the fastest sailing ships ever built. They had more sails and sleek hulls, sacrificing cargo space for speed. Clippers needed larger crews but could travel much faster than regular sailing ships.

Clippers averaged about 120 days for the 17,000-mile (27,000 km) trip between East Coast cities and San Francisco, about 80 days faster than conventional sailing ships. They often carried high-value cargo and a few passengers.

Routes to California

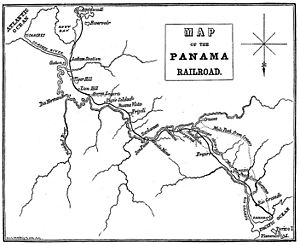

- Via Panama/Nicaragua/Mexico: This was the fastest route, taking 30-90 days. Travelers would take a steamer to the Caribbean side of Panama, cross the narrow land by dugout canoe and mule, then catch another steamer on the Pacific side to California. This route was risky due to disease and bandits. The Panama Railroad, completed in 1855, made the Panama route much easier and faster.

- Via Cape Horn: This all-sea route around the tip of South America was the cheapest but longest, taking about 200 days (over 6 months). It was the main route for shipping heavy or bulky goods. Passengers often faced sea-sickness, monotonous food, and long periods at sea. Ships would stop in ports like Rio de Janeiro or Valparaíso for fresh supplies.

- From China: News of the Gold Rush reached China by late 1848, leading to a steady flow of Chinese immigrants, mostly young men, to California. They often booked passage on American clipper ships or Pacific Mail Steamship Company vessels. Many planned to return to China after making enough money.

California Fisheries: Harvesting the Ocean

California has a long history of fishing, going back over 10,000 years with its Native American inhabitants.

Native American Fishing Methods

Native Americans in California were mostly hunter-gatherers, and fish and shellfish were a big part of their diet. They caught salmon and steelhead in rivers and streams using spears, harpoons, nets, traps, hooks, and even plant poisons to temporarily stun fish. They would smoke or sun-dry fish to store them for later.

The Chumash and Tongva people used their tomol canoes to fish in the ocean, catching sardines and other fish with nets. Along San Francisco Bay, Native Americans built huge shell mounds from millions of discarded oyster and shellfish shells, showing how important these foods were. Tule canoes were also used for fishing in the Bay Area's wetlands.

Modern Fisheries and Challenges

After the Gold Rush, many new immigrants, especially from Portugal and China, started fishing in California. Chinese fishermen, for example, used sampans to catch squid and abalone in Monterey Bay.

In the early 1900s, the sardine fishery grew rapidly. New technologies like the "lampra" net, which could scoop up large schools of fish, made fishing more efficient. Monterey became a major canning town, processing sardines for food and for "reduction" into fertilizer and animal feed. However, by the 1950s, sardine populations greatly decreased due to overfishing and changes in ocean temperature.

Today, fishing vessels use diesel engines for power and advanced techniques like different types of nets (seine, trawl, gillnet) and longline fishing. To keep fish fresh, they are stored in refrigerated holds or packed in ice.

Overfishing is a big problem for many fisheries worldwide. To protect fish populations, California has set up quotas, catch limits, and fishing seasons. The California Department of Fish and Game works to enforce these laws and manage fish hatcheries to help stock waters. The Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary is a protected area that helps preserve marine life.

California is home to important naval bases that have played a big role in U.S. history.

Mare Island, near Vallejo, California, became the first permanent U.S. naval base on the West Coast in 1854. It was chosen because it was safe from ocean storms. David Farragut, a famous naval officer, was its first commander.

For over a century, Mare Island Naval Shipyard built and repaired many types of ships, from battleships to submarines. During World War II, it specialized in building diesel-powered submarines, constructing 32 of them. After the war, it became a key site for building nuclear-powered submarines, building 27 more.

Mare Island Naval Shipyard closed in 1996, but its history as a major shipbuilding center is very important.

Naval Base San Diego was established in 1920 and is now the largest base of the United States Navy on the West Coast. It is home to a huge naval fleet, including supercarriers, and supports over 120 different naval commands. The base covers a large area of land and water, with many piers for ships.

California Shipbuilding: Building Ships for the Nation

California shipbuilders have been constructing and repairing ships since the mid-1850s. During both World War I and World War II, many shipyards were built in California to support the war effort, building ships from steel, wood, and even concrete.

Some of the major shipyards included:

- California Shipbuilding Corporation (Calship): Located in Los Angeles, Calship built 467 Liberty and Victory ships during World War II.

- Kaiser Richmond Shipyards: These four shipyards in Richmond, California, built more Liberty ships (747) than any other shipyard in the U.S. during World War II. They were known for building ships very quickly and efficiently.

- National Steel and Shipbuilding Company (NASSCO): Located in San Diego, NASSCO started as a small machine shop in 1905. Today, it is the largest new ship construction shipyard on the West Coast, building commercial cargo ships and auxiliary vessels for the U.S. Navy.

.

California Ports: Gateways to the World

California has many important ports along its coast, from small fishing harbors to huge container terminals. These ports are vital for trade, tourism, and military operations.

Some major ports include:

- Port of Long Beach and Port of Los Angeles: These are two of the busiest container ports in the United States, handling massive amounts of cargo.

- Port of Oakland: Another large container port in the San Francisco Bay Area.

- Port of San Diego: A major port for cruise ships, lumber, and automobiles, as well as home to a large naval base.

- Port of San Francisco: Historically important during the Gold Rush, it now handles cruise ships and general cargo.

These ports connect California to the rest of the world, bringing in goods and supporting many industries.

Ferry Service: Crossing the Waters

San Francisco Bay has had ferry services for over 150 years. While bridges reduced their importance, some passenger ferries still operate today for commuters and tourists. Ferries also connect San Diego to Coronado and serve Santa Catalina Island.

Shipwrecks: Dangers at Sea

California's rocky coastline, frequent fogs, and strong winds have always made shipping dangerous. Many ships have been wrecked along the coast.

One of the earliest recorded shipwrecks was the Spanish galleon San Augustin, which was driven ashore in 1595 in Drakes Bay.

The Honda Point disaster in 1923 was the largest peacetime loss of U.S. Navy ships. Seven destroyers ran aground at Honda Point due to a navigation error, and 23 men died.

California keeps a database of all known shipwrecks, including their locations and details. These wrecks are reminders of the challenges of sea travel.

Lighthouses: Guiding Ships Safely

Lighthouses are towers or buildings with bright, flashing lights that warn ships of dangers and help them navigate, especially at night or in fog. They mark dangerous coastlines, rocks, and harbor entrances.

In the 1850s, lighthouses used oil or kerosene lamps with special Fresnel lenses to focus the light. Clockwork mechanisms, powered by falling weights, rotated the lights. Lighthouse keepers, sometimes called "wickies," had to constantly trim wicks, refuel lamps, and keep the equipment clean.

The first lighthouses in California were built in the 1850s, after the Gold Rush greatly increased ship traffic. The lighthouse on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay was one of the first, operating by 1855. More than 45 lighthouses were eventually built along the California coast.

Today, most lighthouses are automated, using electricity or solar power. The United States Coast Guard maintains them and publishes a list of all aids to navigation. Despite modern electronic navigation, lighthouses remain important symbols of safety at sea.

Images for kids

-

A typical river paddle steamer from the 1850s.

-

The Cabrillo National Monument in San Diego, California

-

Trade winds used by the Manila galleons to get to and from Guam and the Philippines--the North Pacific Gyre

-

USS Cyane taking San Diego 1846

-

The Showboat Branson Belle on Table Rock Lake in Branson, Missouri, is a stern-wheeler showboat. It is run aground in this picture.

-

Britannia of 1840 (1150 GRT), the first Cunard liner built for the transatlantic service.

-

SS California (1848), the first paddle steamer to steam between Panama City and San Francisco--a Pacific Mail Steamship Company ship.

-

Colombian training ship ARC Gloria at sunset in Cartagena, Colombia

-

Aerial view of San Francisco Bay looking east from the Pacific.

-

Satellite view of Veracruz

-

Artist's conception of the proposed canal showing the San Juan River, Lake Nicaragua and the Caribbean Sea

-

Double-rigged shrimp trawler hauling in the nets

-

USS Tang off Mare Island in 1943.

-

Hospital ship Mercy leaving San Diego in May 2008.

-

Victory ship SS Red Oak Victory (AK-235), now a museum ship]].

-

SS John W. Brown is one of only two surviving operational Liberty ships.