Honda Point disaster facts for kids

Aerial view of the disaster area, showing all seven destroyers. Photographed from a plane assigned to USS Aroostook. The ships are Nicholas and S. P. Lee at the top left. Delphy, capsized and broken in the small cove at left; Young, capsized in left center; Chauncey, upright ahead of Young; Woodbury on the rocks in the right center; and Fuller on the rocks at right.

|

|

| Date | September 8, 1923 |

|---|---|

| Time | 21:05 local |

| Location | Honda (Pedernales) Point, near Lompoc, Santa Barbara County, California, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 34°36′11″N 120°38′43″W / 34.60306°N 120.64528°W |

| Casualties | |

| 23 dead | |

| Numerous injuries | |

The Honda Point disaster was the biggest loss of U.S. Navy ships during peacetime. On the evening of September 8, 1923, seven destroyers, traveling at 20 knots (37 km/h), crashed into rocks at Honda Point. This area is also known as Point Pedernales or Devil's Jaw. It's located a few miles from the northern side of the Santa Barbara Channel in California. Two other ships also hit the rocks but managed to get free. Sadly, twenty-three sailors died in this disaster.

Contents

Geography of Honda Point

The area around Honda Point is very dangerous for ships sailing along the central California coast. It has many rocky areas, which are known together as Woodbury Rocks. One of these rocks is even called Destroyer Rock on maps today. This tricky area, known as the Devil's Jaw, has been a hazard for ships since Spanish explorers first arrived in the 1500s. It is just north of the entrance to the Santa Barbara Channel, which was where the destroyers involved in the disaster were planning to go.

Honda Point today

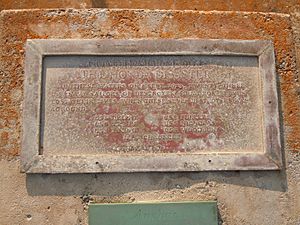

Honda Point, also called Point Pedernales, is on the coast at Vandenberg Air Force Base, near the city of Lompoc, California. There is a special plaque and a memorial there to remember the disaster. The memorial includes a ship's bell from the ship Chauncey. You can also see a propeller and a propeller shaft from the Delphy outside the Veterans' Memorial Building in Lompoc, California.

The Incident

On September 8, 1923, fourteen ships from Destroyer Squadron Eleven (DesRon 11) were sailing south. They were going from San Francisco Bay to San Diego Bay. Captain Watson was in charge, and his flag was on the USS Delphy. All these ships were Clemson-class destroyers, which means they were less than five years old.

At 9:00 PM, the ships turned east, aiming for the Santa Barbara Channel. The ships were using a method called dead reckoning to figure out their location. This means they estimated their position based on their speed and direction. At that time, radio navigation tools were new and not fully trusted.

The USS Delphy had a radio navigation receiver. However, its captain, Lieutenant Commander Donald T. Hunter, who was also the squadron's navigator, didn't trust the readings from it. He thought they were wrong. The ships also didn't use a fathometer to measure water depths. This would have required them to slow down.

The ships were practicing for wartime conditions, and Captain Watson wanted to reach San Diego quickly. So, they decided not to slow down. Even though there was heavy fog, Captain Watson ordered all ships to stay close together. He turned the ships too early, and the lead ship, Delphy, ran aground. Six other ships followed and sank. Two ships whose captains didn't follow the close-formation order survived, even though they also hit the rocks.

Earlier that same day, another ship, the mail steamship SS Cuba, also ran aground nearby. Some people thought these accidents in the Santa Barbara Channel were caused by unusual currents. These currents might have been due to the great Tokyo earthquake that happened the week before.

Ships Involved

The ships that were lost were:

- USS Delphy (DD-261): This was the lead ship. It hit the shore while going 20 knots (37 km/h). After hitting the rocks, it blew its siren, which helped warn other ships. Three of its crew members died.

- USS S. P. Lee (DD-310): This ship was a short distance behind. When it saw the Delphy stop suddenly, it turned left and also ran aground on the coast.

- USS Young (DD-312): This ship didn't turn. It ripped open its bottom on hidden rocks, and water rushed in, causing it to flip over onto its side. Twenty sailors died on this ship.

- USS Woodbury (DD-309): This ship turned right but hit a rock offshore.

- USS Nicholas (DD-311): This ship turned left and also hit a rock.

- USS Fuller (DD-297): This ship got stuck right next to the Woodbury.

- USS Chauncey (DD-296): This ship ran aground while trying to rescue sailors from the flipped-over Young.

Ships that had light damage:

- USS Farragut (DD-300): This ship ran aground but was able to get itself free and was not lost.

- USS Somers (DD-301): This ship had only minor damage.

The five ships that avoided the rocks were:

- USS Percival (DD-298)

- USS Kennedy (DD-306)

- USS Paul Hamilton (DD-307)

- USS Stoddert (DD-302)

- USS Thompson (DD-305)

Rescue Efforts

Right after the accident, rescue efforts began quickly. Local ranchers, who heard the noise from the disaster, set up breeches buoys. These are special ropes and seats that they lowered from the cliffs to the ships that had run aground. Nearby fishermen who saw what happened picked up crew members from the USS Fuller and USS Woodbury.

The surviving crew members from the flipped-over Young were able to climb to safety on the nearby USS Chauncey using a lifeline. The five destroyers from Destroyer Squadron Eleven that didn't run aground also helped. They picked up sailors who had fallen into the water and helped those stuck on the damaged ships.

After the disaster, the government didn't try to recover any of the wrecked ships at Honda Point. This was because the ships were too badly damaged. The wrecks and any equipment left on them were sold to a scrap dealer for a total of $1,035. The wrecked ships were still there in August 1929. You can even see them in film footage taken from the German airship Graf Zeppelin as it flew towards Los Angeles.

Court-Martial

A group of seven Navy officers held a special military trial, called a court-martial. They decided that the disaster was the fault of the fleet commander and the navigators on the lead ship. They also blamed the captain of each ship that ran aground. This is because a captain's main job is always to keep their own ship safe, even when sailing in a group. Eleven officers were put on trial for not doing their duty well enough. This was the largest group of officers ever court-martialed in the U.S. Navy's history.

The court-martial decided that the Honda Point Disaster happened because of "bad errors and faulty navigation" by Captain Watson. Watson lost some of his rank in line for promotion, and three other officers received warnings.

All the officers who were court-martialed were found not guilty.

Captain Watson was praised by his fellow officers and the government for taking full responsibility for the disaster. He could have tried to blame other things, but instead, he accepted all the responsibility himself.

Another investigation recommended that Commander Roper receive a special commendation. This was because he turned his division of ships away from danger, which saved them.

Captain Edward Howe Watson

Captain Edward H. Watson graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1895. He had served in the Spanish–American War, the Philippine Insurrection, and World War I. Watson was promoted to captain in 1917. He became the commodore of Destroyer Squadron Eleven (DesRon 11) in July 1922. This was his first time leading a whole unit of ships.

The fourteen Clemson-class destroyers of Destroyer Squadron Eleven were supposed to follow the lead ship, USS Delphy. They were sailing in a line from San Francisco Bay, through the Santa Barbara Channel, and then to San Diego. This was a twenty-four-hour training exercise. The lead ship was in charge of finding the way. As the Delphy sailed along the coast, it was hard to see because of poor visibility. So, the navigators had to use an old method called dead reckoning. They had to guess their position based on their speed and direction. The captain of the Delphy was also acting as the squadron's navigator. He overruled his ship's actual navigator, Lieutenant (junior grade) Lawrence Blodgett. The Delphy did have radio direction finding (RDF) equipment. This equipment picked up signals from a station at Point Arguello. However, RDF was new, and the captain thought the readings were not reliable. Based only on dead reckoning, Captain Watson ordered the fleet to turn east into the Santa Barbara Channel. But the Delphy was actually several miles northeast of where they thought they were. This mistake caused the ships to crash into Honda Point.

The Kennedy ship received radio signals that showed the correct positions of the Delphy and the Stoddert. This allowed the Kennedy to know exactly where the fleet was. When the Kennedy reached the turning point, Commander Walter G. Roper, who was in charge of Division 32 (which included Kennedy, Paul Hamilton, Stoddert, and Thompson) at the back of the line, ordered his ships to slow down and then stop. This action helped them avoid hitting the rocks.

Ocean Conditions

At his military trial, Lieutenant Commander Hunter, the navigator of the Delphy, spoke about the disaster. He said, "I think there is also a possibility that abnormal currents caused by the Japanese earthquake might have been another contributing cause." On September 1, 1923, just seven days before the disaster, a huge earthquake, the Great Kantō earthquake, happened in Japan. Very large waves and strong currents appeared off the coast of California and stayed for several days. Before Destroyer Squadron Eleven even reached Honda Point, other ships had problems navigating because of these unusual currents.

As the Destroyer Squadron Eleven began their journey down the California coast, they sailed through these large waves and currents. While the squadron was traveling, their guesses about speed and direction for dead reckoning were being affected. The navigators on the lead ship Delphy did not consider how the strong currents and big waves would change their calculations. Because of this, the entire squadron was off course. They were near the dangerous coastline of Honda Point instead of in the open ocean of the Santa Barbara Channel. Along with the darkness and thick fog, the waves and currents from the earthquake in Japan made it almost impossible for the Delphy to navigate accurately using dead reckoning. The geography of Honda Point, which is open to wind and waves, became a deadly place once the unusually strong waves and currents pushed the ships into the rocks.

Once the navigation mistake happened, the weather and ocean conditions sealed the squadron's fate. The weather around Honda Point during the disaster was windy and foggy. The area's geography also created strong counter-currents and waves that forced the ships into the rocks once they entered the area.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Desastre de Honda Point para niños

In Spanish: Desastre de Honda Point para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |