History of California before 1900 facts for kids

The story of California began about 13,000 years ago when the first Native Americans arrived. Later, in the 1500s, Spanish explorers started sailing along the coast. More European settlers came in the 1700s, building towns and missions.

California was part of New Spain (which later became Mexico) until 1848. After the Mexican–American War, it became part of the United States. In the same year, the California Gold Rush started, bringing many people to the area. California joined the U.S. as a free state in 1850. By the end of the 1800s, California was mostly farmland, with about 1.4 million people living there.

Contents

Native American Life in California

Scientists believe the first people came to the Americas from Asia about 16,500 years ago, crossing a land bridge. Some of the oldest signs of people in California are from about 13,000 years ago on Santa Rosa Island.

Many different Native American tribes and language groups lived in California. This made California one of the most diverse areas in North America for native cultures. Some of the tribes included the Chumash, Maidu, Miwok, Modoc, Mohave, Ohlone, Pomo, Serrano, Shasta, Tataviam, Tongva, Wintu, and Yurok.

These tribes learned to live in California's many different climates. Coastal tribes made trading beads from shells. Tribes in the Central Valley used fire to help edible plants grow, especially oak trees. They ground acorns into flour for food. Mountain tribes fished for salmon and hunted game. They also used obsidian (a volcanic rock) for tools and trade. Desert tribes learned to survive in harsh areas by using local plants and living near water. Native Americans also used controlled fires to manage forests and grasslands. This helped new plants grow and attracted animals for hunting.

When Europeans first arrived in the 1700s, about 300,000 Native Americans lived in California. This was about one-third of all native people in what is now the United States.

European Exploration (1530–1765)

From the early 1500s to the mid-1700s, explorers from Spain and England sailed along California's coast. But no European settlements were built yet. Spain was focused on its main colonies in Mexico and Peru. They believed all lands touching the Pacific Ocean belonged to them. The explorers saw hilly grasslands and wooded areas, but not many obvious resources or good ports.

Other European countries didn't pay much attention to California at first. It wasn't until the mid-1700s that Russian and British explorers and fur traders started setting up stations on the coast.

Early Spanish Voyages

Around 1530, stories spread about a land filled with gold, pearls, and gems. Hernán Cortés was interested in these tales. In 1535, he claimed the Baja California Peninsula for Spain.

In 1539, Francisco de Ulloa sailed to the mouth of the Colorado River and around the peninsula. His journey was the first time the name "California" was recorded. It came from a popular book about a fictional island called "California."

First European to Explore the Coast

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo is thought to be the first European to explore the California coast. He sailed for Spain. In 1542, he landed at San Diego Bay on September 28, claiming the land for Spain. He continued north, naming the channel islands. On October 8, he came ashore at San Pedro Bay (now the port of Los Angeles), which he called "bay of smoke" because of the many cooking fires of the native Chumash people. Cabrillo died during this trip, but his crew continued exploring as far north as what is now southern Oregon.

English Explorer Sir Francis Drake

In 1579, the English explorer Sir Francis Drake found a good harbor. He called the land "Nova Albion" and claimed it for England. This place is believed to be in Drakes Bay. No English settlements followed this claim.

Sebastián Vizcaíno's Detailed Maps

In 1602, the Spaniard Sebastián Vizcaíno explored California's coastline up to Monterey Bay. He made detailed maps of the coastal waters, which were used for almost 200 years. He also wrote glowing reports about Monterey as a good place for ships and settlements.

European Exploration (1765–1821)

Spanish ships trading with China likely stopped in California every year after 1680. By the late 1700s, wars between Britain and Spain were increasing. In 1762, Britain took over Manila in the Pacific and Havana in the Atlantic. This likely encouraged Spain to build military forts (presidios) in San Francisco and Monterey in 1769.

British explorers also became more active. In 1778, Captain James Cook mapped the coast from California to the Bering Strait. In 1786, French explorers led by Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse visited Monterey. They wrote about the Spanish missions, the land, and the people. More traders, whalers, and scientific groups visited in the following decades.

Spanish Colonization (1697–1821)

In 1697, Jesuit missionaries, with financial help, started expanding into California. Juan María de Salvatierra established the first permanent mission on the Baja California Peninsula. Spanish control slowly grew, with 30 missions eventually built in Baja California.

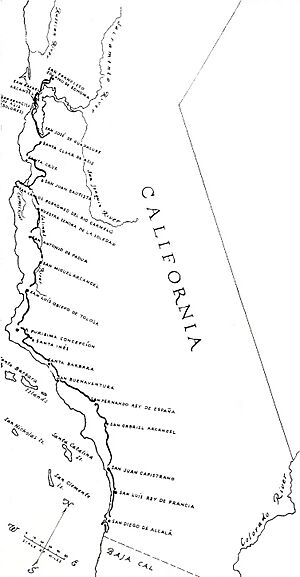

In the late 1700s, Spain began building settlements in what became Alta California (present-day California). They were worried about Russia and Britain expanding into the Pacific Northwest. Spain built Catholic missions, protected by soldiers, along the southern and central coast of California. These missions showed Spain's claim to the land. By 1823, 21 Spanish missions were built in Alta California.

By 1820, Spanish influence stretched from Loreto in the south to just north of the San Francisco Bay Area. This influence extended about 25 to 50 miles inland from the missions. Outside this area, about 200,000 to 250,000 Native Americans still lived traditional lives. In 1819, a treaty set the northern boundary of Spanish claims at the 42nd parallel, which is now the border between California and Oregon.

First Spanish Colonies in Alta California

Spain had missions and forts in New Spain since 1519. But settling northern New Spain was slow. Settlements in Loreto, Baja California Sur, began in 1697. However, it wasn't until 1765, when Russia started moving south from Alaska, that Spain decided to build more settlements further north.

Spain was busy with the aftermath of the Seven Years' War, so they put only a small effort into California. Franciscan Friars were sent to settle Alta California, protected by soldiers in the California missions. Between 1774 and 1791, Spain sent expeditions to explore and settle Alta California and the Pacific Northwest.

The Portolá Expedition

In 1768, José de Gálvez planned a large expedition to settle Alta California. Gaspar de Portolá volunteered to lead it.

The Portolá land expedition arrived at present-day San Diego on June 29, 1769. They set up the Presidio of San Diego, a military fort. Portolá and his group then headed north on July 14. They reached Los Angeles on August 2, Santa Monica on August 3, and Santa Barbara on August 19. They were looking for Monterey Bay but didn't recognize it when they reached it on October 1.

On October 31, Portolá's explorers became the first Europeans known to see San Francisco Bay. It's interesting because Spanish ships had sailed along this coast for almost 200 years without noticing the bay. The group returned to San Diego in 1770. Portolá became the first governor of Las Californias.

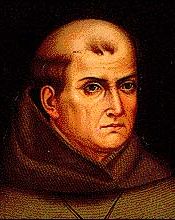

Junípero Serra and the Missions

Junípero Serra was a Franciscan friar from Majorca, Spain. He founded the first Spanish missions in Alta California. After the Jesuits were ordered to leave New Spain in 1768, Serra was put in charge of the missions.

Serra founded Mission San Diego de Alcalá in 1769. Later that year, he and Governor Portolá traveled north. They reached Monterey in 1770, where Serra founded the second Alta California mission, Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo.

Alta California Missions and Life There

The California missions were religious outposts built by Spanish Catholic groups (Dominicans, Jesuits, and Franciscans). Their goal was to teach Christianity to the local Native Americans. Most of the money for Spain's California program went to military forts to keep Britain and Russia out, not just to the missions. The main reason Spain occupied California was to claim the territory during imperial wars with Britain.

The missions brought European animals, fruits, vegetables, and farming methods to California. Many people believe Native Americans were forced to work at the missions. However, some historians suggest that the small number of Spaniards at each mission relied more on talking, offering things, and sometimes threatening force to control the thousands of Native Americans living near the missions. The missionaries and soldiers often had different ideas about California's future.

Most missions became very large, covering areas the size of modern counties. But the Spanish and Mexican staff was small, usually two Franciscans and six to eight soldiers. The number of Native Americans living at the missions grew over time. Native people built all the mission buildings under Franciscan guidance.

After 1810, the missions lost their funding because the Spanish Empire was collapsing. Native Americans at the missions were pressured to produce more goods. The missions then exported these goods through American and Mexican traders. After Mexico became independent in 1821, the use of unpaid Native American labor at missions to support Mexican forts became common.

The missions were one of three main ways Spain tried to control its colonies. The other two were the presidio (royal fort) and pueblo (town). None of the missions could fully support themselves and needed financial help.

When the Mexican War of Independence started in 1810, this support mostly disappeared. The missions and the Native Americans living there were left on their own. By 1827, the Mexican government ordered all Spanish-born people to leave Mexico. This greatly reduced the number of priests in California. Some missions were taken over by the Mexican government and sold. After California became a U.S. state, the U.S. Supreme Court returned some missions to the religious orders that owned them.

To make travel easier, the missions were built about 30 miles apart. This was about a day's ride on horseback along the 600-mile-long El Camino Real, or "the Royal Road." Today, it's also called the "King's Highway" or "California Mission Trail." Legend says the priests sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail to mark it with bright yellow flowers.

Four military forts, called presidios, were placed along the California coast. They protected the missions and other Spanish settlements. Many mission buildings still exist today or have been rebuilt. The highway and missions became a symbol of a peaceful past for many.

Ranchos and Their Role

The Spanish encouraged settlement by giving out large land grants called ranchos. On these ranchos, cattle and sheep were raised. After Mexico gained independence, the mission lands were divided into more ranchos. Cow hides and fat (tallow, used for candles and soap) were California's main exports until the mid-1800s.

The owners of these ranchos were called "Dons." The workers on the ranchos were mostly Native Americans, many of whom had lived at the missions and learned Spanish and how to ride horses. Some ranchos were even given directly to Native Americans.

Administrative Divisions

In 1773, a border was set between the missions in Baja California and Alta California. By 1804, because more Spanish-speaking people lived in Alta California, the province of Las Californias was divided into two separate areas: Baja California (Lower California) and Alta California (Upper California). Alta California's eastern borders were not clearly defined, so it included parts of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming.

Russian Presence in California

Part of Spain's reason for settling Alta California was to stop Russia and Britain from moving into their territory. In the early 1800s, Russian fur traders from Alaska explored down the West Coast, hunting for sea otter furs. In 1812, the Russian-American Company built a fortified trading post called Fort Ross near present-day Bodega Bay. This was about 60 miles north of San Francisco, on land claimed by Spain but not settled. The Russians stayed there until 1841.

In 1836, General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo established the Sonoma Barracks. This was part of Mexico's plan to stop Russian expansion into the area, just as the Sonoma Mission had been for the Spanish.

California Under Mexican Rule (1821–1846)

Changes Under Mexican Rule

Many changes happened in California during the early 1800s. By 1809, Spain was no longer truly governing California because their king was imprisoned. For the next 15 years, the colony relied on trade with Americans and other Spanish-Americans. Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. This officially began Mexican rule in California, though Mexico didn't fully control the area until 1825.

The Native American communities at the missions and the missionaries were key to California's economy between 1810 and 1825. Ranching and trade grew, while converting new Native Americans became less important.

Mexico's new government included Alta California and Baja California as territories. In 1823, Mexico became a republic. Alta California was not made a state because it had a small population. The 1824 Mexican Constitution called Alta California a "territory." Mexico didn't send a governor to California until 1825, when José María de Echeandía arrived. He began efforts to free Native Americans from the missions and allowed soldiers to get ranches where they used Native American labor. There was growing pressure to close the missions, which held much of the fertile land.

By 1829, many powerful missionaries had left. In 1827, Mexico passed a law ordering all Spanish-born people to leave the country. Many of the aging missionary priests were Spanish and felt pressured to go.

In 1831, wealthy citizens in Alta California asked Governor Manuel Victoria for democratic changes. They preferred the previous governor, Echeandía. They formed a small army, took over Los Angeles, and fought Victoria's army. Victoria was wounded and resigned. Echeandía became governor again until José Figueroa took over in 1833.

Next, in 1833, the Mexican Congress passed a law to secularize (take control of) the California missions. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to be affected in 1834. This law allowed the military to distribute the Native Americans' land among themselves. Some older Franciscans never left the missions.

In 1836, Mexico changed its government to be more centralized. Alta and Baja California were reunited into one California Department. But this change didn't have much effect in far-off Alta California. The capital remained Monterey, and local politics stayed the same.

In 1836, Nicolás Gutiérrez became interim governor, followed by Mariano Chico, who was unpopular. Gutiérrez took over again but was also unpopular. Local leaders Juan Bautista Alvarado and José Castro, with help from Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo and a group of Americans, started a revolt in November 1836. They forced Gutiérrez to give up power. The Americans wanted California to be independent, but Alvarado wanted it to remain part of Mexico, but with more self-rule.

In 1840, an American named Isaac Graham was accused of planning a revolt like the one in Texas. Alvarado told Vallejo, and in April, the Californian military arrested about 100 American and English immigrants. They were sent to San Blas to be deported. American and British diplomats helped get the remaining prisoners released. In 1841, Graham and 18 others returned to Monterey with new passports.

Also in 1841, U.S. leaders talked about "Manifest Destiny," the idea that the U.S. should expand across the continent. Californios (Spanish-speaking Californians) became worried about American intentions. Vallejo, Castro, and Alvarado asked Mexico to send more soldiers to control California.

In response, Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna sent General Manuel Micheltorena and 300 soldiers to California in 1842. Micheltorena was to become governor and military commander. In October, before he reached Monterey, American Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones mistakenly thought war had started between the U.S. and Mexico. He sailed into Monterey Bay and demanded the fort surrender. Alvarado reluctantly gave up. The next day, Jones realized his mistake.

Micheltorena eventually reached Monterey, but his troops, some of whom were unruly, caused problems. This led to rumors of a revolt. By 1844, Alvarado joined those who were unhappy. Micheltorena ordered his arrest, but it was short-lived because Micheltorena needed everyone to prepare for war against the U.S.

This plan backfired. On November 14, 1844, Californios led by Manuel Castro revolted against Mexican authority. José Castro and Alvarado led the troops. There was no actual fighting at first, and a truce was made. Micheltorena agreed to send away his unruly troops. But he broke the agreement, and fighting began. The rebels won the Battle of Providencia in February 1845, and Micheltorena and his troops left California.

Pío Pico became governor in Los Angeles, and José Castro became the military commander. Alvarado was elected to the Mexican Congress. Relations between northern Alta California (with more Americans) and southern Alta California (where Californios were stronger) became tense.

John C. Frémont arrived in Monterey in early 1846. Castro gathered his militia, with Alvarado as second-in-command, fearing foreign aggression. But Frémont went north to Oregon instead. The political situation in Mexico was unstable, and it seemed civil war might break out between northern and southern California.

By 1846, Alta California had fewer than 10,000 Spanish-speaking people. Most were Californios living on large ranchos. There were also about 1,300 American citizens and 500 Europeans, mostly traders. The number of adult men in both groups was about equal, but the Americans were newer arrivals.

Other Nationalities in California

The Russian-American Company built Fort Ross in 1812. It was their southernmost colony in North America, meant to supply their northern posts with food. The fort remained Russian until 1841.

During this time, American and British traders came to California looking for beaver furs. They used trails like the Siskiyou Trail and California Trail. These traders often arrived without Mexico's permission. They helped set the stage for the many people who would come during the California Gold Rush.

In 1840, Richard Henry Dana Jr. wrote about his experiences on a ship off California in the 1830s in his book Two Years Before the Mast.

A French explorer, Eugène Duflot de Mofras, wrote in 1840 that California would belong to any nation that sent a warship and 200 men. In 1841, General Vallejo worried that France was trying to take California. The German-Swiss John Sutter even threatened to raise the French flag over his settlement, New Helvetia, if he had problems with Mexicans.

American Interest and Immigrants

While some American traders and trappers lived in California since the 1830s, the first organized group of American immigrants to travel overland was the Bartleson–Bidwell Party in 1841. They traveled across the continent using the new California Trail. In 1844, Caleb Greenwood guided the first settlers to bring wagons over the Sierra Nevada mountains. In 1846, the Donner Party faced terrible hardships trying to enter California.

California Under American Rule (Beginning 1846)

Population Growth

The non-Native American population of California in 1840 was about 8,000. The Native American population is harder to know, but estimates range from 30,000 to 150,000 in 1840. By 1850, the population had grown to about 120,000, not counting Native Americans. There were very few women in California at this time, only about 10,000 in 1850.

By California's special 1852 State Census, the population had reached about 200,000. About 10% of these were women. Travel to California became easier and cheaper, especially after the Panama Railroad was completed in 1855. Many successful Californians sent for their wives and families to join them. The number of men and women in California didn't become equal until the 1950s.

Bear Flag Revolt and American Conquest

When the United States declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846, it took almost two months for the news to reach California. Hearing rumors of war, U.S. consul Thomas O. Larkin in Monterey tried to keep peace between Americans and the small Mexican military led by José Castro. American army captain John C. Frémont, with about 60 armed men, had entered California in December 1845. He was heading to Oregon when he heard war was likely.

On June 15, 1846, about 30 non-Mexican settlers, mostly Americans, revolted. They seized the small Mexican fort in Sonoma and captured Mexican general Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. They raised the "Bear Flag" over Sonoma. This "California Republic" lasted only one week. On June 23, the U.S. Army, led by Frémont, took over. Today's California state flag is based on this original Bear Flag and still says "California Republic."

Commodore John Drake Sloat, hearing of the war and revolt, ordered his navy to occupy Yerba Buena (now San Francisco) on July 7 and raise the American flag. On July 15, Sloat gave command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a more aggressive leader. Stockton put Frémont's forces under his command. Frémont's "California Battalion" grew to about 160 men with new American volunteers. On July 19, he entered Monterey with some of Stockton's sailors and marines. The official news of the Mexican–American War had arrived. American forces easily took control of northern California, including Monterey, San Francisco, Sonoma, and Sutter's Fort, within days.

In Southern California, Mexican General José Castro and Governor Pío Pico fled Los Angeles. When Stockton's forces entered Los Angeles without resistance on August 13, 1846, it seemed California was conquered easily. However, Stockton left too few soldiers (36 men) in Los Angeles. The Californios, led by José María Flores, forced the small American group to leave in late September.

Two hundred more soldiers were sent by Stockton, led by US Navy Captain William Mervine. But they were pushed back in the Battle of Dominguez Rancho in October 1846, near San Pedro, where 14 US Marines died. Meanwhile, General Stephen W. Kearny and about 100 soldiers finally reached California after a difficult march. On December 6, 1846, they fought the Battle of San Pasqual near San Diego, where 18 of Kearny's soldiers were killed. This was the largest number of American deaths in battle in California.

Stockton rescued Kearny's surrounded forces. With their combined strength, they moved north from San Diego. On January 8, they joined Frémont's northern force. With 660 American troops, they fought the Californios in the Battle of Río San Gabriel. The next day, January 9, 1847, they fought the Battle of La Mesa. Three days later, on January 12, 1847, the last large group of Californios surrendered. This marked the end of the war in California. On January 13, 1847, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed.

More American troops continued to arrive in California. All these troops were still in California when gold was discovered in January 1848.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, officially ended the Mexican–American War. In this treaty, the United States agreed to pay Mexico $18,250,000. Mexico formally gave California (and other northern territories) to the United States. The treaty also drew the first international border between the U.S. and Mexico. The border was slanted to include all of San Diego Bay in California, as it was a valuable natural harbor.

The California Gold Rush

In January 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in the Sierra Nevada foothills, about 40 miles east of Sacramento. This started the California Gold Rush, which had the biggest impact on California's population growth.

Miners and merchants settled in towns along what is now Highway 49. New settlements also appeared along the Siskiyou Trail as gold was found in other parts of California. San Francisco Bay was the closest deep-water port, so San Francisco became a center for bankers who helped fund gold exploration.

The Gold Rush brought people from all over the world to California. By 1855, about 300,000 "Forty-Niners" had arrived from every continent. Many left soon after, some rich, most not. The Native American population dropped sharply in the decade after gold was discovered.

Becoming a State: 1849–1850

From 1847 to 1849, the U.S. military governed California. Local governments were run by alcaldes (mayors), some of whom were Americans. Bennett C. Riley, the last military governor, called a meeting in Monterey in September 1849 to create a state constitution. The 48 delegates were mostly American settlers who had arrived before 1846. Eight were Californios. They all agreed to outlaw slavery. They set up a state government that operated for 10 months before California officially became a state on September 9, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850. After Monterey, the state capital moved to San Jose, then Vallejo, then Benicia, until Sacramento was chosen in 1854.

Californios and people from the Southern U.S. in rural Southern California tried three times in the 1850s to create a separate state or territory. The last attempt in 1859, the Pico Act, was passed by the California State Legislature and approved by voters. But the political conflicts leading to the Civil War in 1860 stopped the proposal from being voted on in Washington, D.C.

California During the Civil War

California played a small role in the American Civil War because it was so far away. Some settlers supported the Confederacy, but they were not allowed to organize, and their newspapers were shut down. Powerful business leaders controlled California's politics through their control of mines, shipping, and money. They controlled the state through the new Republican Party. Most men who volunteered as soldiers stayed in the West to guard places, keep order, or fight Native Americans. About 2,350 men in the California Column marched east in 1862 to remove Confederates from Arizona and New Mexico. They then spent most of the war fighting Native Americans in that area.

Labor and Workers' Rights

California Senator David C. Broderick once said that there was no place where labor was "so honored and so well rewarded" as in California. Early immigrants brought many skills, and some came from places where workers were already organizing. California's labor movements began in San Francisco, which was the only large city in California for decades and a center for unions in the West.

Because San Francisco was somewhat isolated, skilled workers could demand better conditions than workers on the East Coast. Printers tried to organize in 1850, teamsters in 1851, bakers and bricklayers in 1852, and carpenters and blacksmiths in 1853. These efforts led to better pay and working conditions and started the long process of creating state labor laws. Between 1850 and 1870, laws were made for paying wages, protecting workers' pay, and establishing the eight-hour workday.

It was said that in the late 1800s, more workers in San Francisco had an eight-hour workday than in any other American city. In 1864, a strike by molders and boilermakers happened because employers threatened fines for anyone who met the strikers' demands. The San Francisco Trades Union sent people to meet a boatload of strikebreakers (people hired to replace striking workers) and convinced them to join the union instead.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, California continued to grow quickly. Small, independent miners were largely replaced by large mining companies. Railroads began to be built, and both railroad and mining companies hired many workers. A major event was the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. This made travel from Chicago to San Francisco take only six days by train, compared to six months by ship. The railroad brought many new workers, ending the time when California labor had special protections. For decades after, labor groups opposed Chinese immigrant workers, and politicians pushed for laws against Chinese people.

Laws were passed in 1852 to make it illegal to bring in enslaved people or "contract" laborers (workers forced into long-term contracts).

The first statewide labor organization was the Mechanics' State Council. It fought for the eight-hour workday against employers who wanted a ten-hour day. By 1872, Chinese workers made up half of all factory workers in San Francisco and were paid much less than white workers. "The Chinese Must Go!" was a popular slogan of Denis Kearney, a labor leader in San Francisco. He led groups that attacked Chinese people and their businesses.

Seamen on the West Coast tried to organize unions twice but failed. In 1875, the Seaman's Protective Association was formed to fight for higher wages and better conditions on ships. This effort was supported by Henry George, editor of the San Francisco Post. Laws were proposed to stop brutal ship captains and require that two-thirds of sailors be Americans. Andrew Furuseth and the Sailors' Union of the Pacific continued this fight for many years.

Labor Politics and Anti-Immigrant Feelings

Thousands of Chinese men came to California to work as laborers, hired by industries for low wages. Over time, conflicts in the gold fields and cities led to unfair treatment of Chinese laborers. During a long economic downturn after the transcontinental railroad was finished, white workers blamed Chinese laborers. Many Chinese were forced out of the mines. Some returned to China, while others moved to Chinatown in San Francisco and other cities, where they were safer from attacks.

From 1850 to 1900, anti-Chinese feelings led to many laws being passed. Many of these laws stayed in effect until the mid-1900s. A clear example was the new state constitution in 1879. Because of strong efforts by the anti-Chinese Workingmen's Party, led by Denis Kearney, a new rule was added. Article XIX, Section 4, said that companies could not hire Chinese "coolies" (a disrespectful term for Chinese laborers). It also gave cities and counties the power to expel Chinese people or limit where they could live. This law was removed in 1952.

The 1879 constitutional meeting also asked Congress for strict immigration limits. This led to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which stopped Chinese laborers from coming to the U.S. The U.S. Supreme Court supported this law in 1889. It was not removed by Congress until 1943. Similar feelings led to the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 with Japan, where Japan agreed to limit emigration to the United States. California also passed an Alien Land Act that prevented people from Asia from owning land. Since it was hard for people born in Asia to become U.S. citizens until the 1960s, their American-born children, who were citizens, held the land titles. This law was overturned by the California Supreme Court in 1952.

In 1886, a Chinese laundry owner challenged a San Francisco law that was clearly designed to put Chinese laundries out of business. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor. This ruling helped create the foundation for modern equal protection laws, which ensure everyone is treated fairly under the law. Even with strict limits on Asian immigration, tensions between unskilled workers and wealthy landowners continued through the Great Depression.

The Rise of Railroads

The "Big Four" were famous railroad leaders who built the Central Pacific Railroad. This railroad formed the western part of the first transcontinental railroad in the United States. They were Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker. Building America's transcontinental rail lines connected California permanently to the rest of the country. The huge transportation systems that grew from these railroads greatly helped California's social, political, and economic growth.

The Big Four controlled California's economy and politics in the 1880s and 1890s. Collis Potter Huntington became one of the most disliked men in California. He was accused of greed and corruption. However, Huntington defended himself, saying his actions helped California more than they helped him.

Later Developments

In 1898, the League of California Cities was founded. This group aimed to fight corruption in city governments, help cities with issues like electricity, and speak for cities to the state government.

Images for kids

-

General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo reviewing his troops in Sonoma, 1846.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |