Pomo facts for kids

|

Pomo woman in traditional dress (2015).

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1770: 8,000 1851: 3,500–5,000 1910: 777–1,200 1990: 4,900 2010: 10,308 |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (California: Mendocino County, Sonoma Valley, Napa Valley, Lake County, Colusa County) | |

| Languages | |

| Pomoan languages, English | |

| Religion | |

| Kuksu, Bole Maru, traditional Pomo religion |

The Pomo are a group of Native American people who have lived in California for thousands of years. Their traditional lands in Northern California stretched from the Pacific Ocean to Clear Lake. This area included parts of Mendocino, Sonoma Valley, Napa, Lake, and Colusa counties.

The name Pomo comes from Pomo words that originally meant "those who live at red earth hole." This name was first used for a village in Potter Valley. It might have referred to the red magnesite used for making red beads, or to the reddish clay soil in the area. Over time, by 1877, the name "Pomo" grew to include all the people who spoke the Pomo language.

Contents

A Look Back: Pomo History

The Pomo people were not a single, unified group. Instead, they lived in many small communities or families. These groups were connected by their location, language, and shared cultural practices.

Life Before European Contact

Scientists believe the Pomo people have lived in California for a very long time. One idea suggests their ancestors moved to the Clear Lake area around 7000 BCE. Another idea places their early community in the Sonoma region. This area had rich natural resources, including redwood forests, valleys, and Clear Lake.

Around 4000 to 5000 BCE, some Pomo people moved to the Russian River Valley and areas near Ukiah. Their language then developed into different Pomoan languages.

Early Settlements and Tools

Archaeological discoveries show that Pomo women processed acorns using mortar and pestles. This important food practice might have started as early as 8500 years ago in the Clear Lake Basin. Early Pomo villages often used millstones for grinding seeds and nuts. These villages might have been temporary camps for hunting. They also used obsidian, a volcanic glass, for tools, though it was rare.

Sacred Sites and Discoveries

At Tolay Lake in southern Sonoma County, over a thousand ancient charmstones and many arrowheads have been found. This site was important to both Pomo and Coast Miwok people. It was a sacred place for ceremonies and healing.

In the Lake Sonoma area, researchers found evidence of human life from around 3280 BCE. This is the oldest known settlement in that valley. Later, during the "Dry Creek" Phase (500 BCE to 1300 CE), Pomo people settled more permanently. They started using bowls, mortars, and pestles, likely for pounding acorns. Trade also grew, with decorative beads, ornaments, and steatite (soapstone) objects being exchanged. The presence of soapstone, which came from far away Catalina Island, shows how large and complex Native California trade networks were.

The "Smith Phase" (1300 CE to mid-19th century) saw more advancements. Archery became a major tool for hunting. The making of shell beads, which were a form of currency, also continued to be very important.

Changes After European Contact

When Europeans first arrived, there were an estimated 8,000 to 21,000 Pomo people living in about 70 different groups. Their lives began to change with the arrival of Russians at Fort Ross (1812–1841) and Spanish missionaries and American settlers. The Pomo living near Fort Ross, known as the Kashaya, traded with the Russians.

Spanish missionaries caused great hardship for many southern Pomo people. Between 1821 and 1828, many were forced to leave their homes and work at missions like Mission San Rafael. This led to difficult living conditions and a significant loss of life. Some Pomo also went to Mission Sonoma.

New Arrivals and Hardships

In the Russian River Valley, a missionary also impacted the Makahmo Pomo people. Many Pomo left their homes to escape these changes. Some moved to more remote areas, gathering together for safety and support.

The Pomo people also suffered greatly from new diseases like cholera and smallpox brought by the newcomers. They had no natural protection against these illnesses, and many people died. A severe smallpox outbreak in 1837 caused many deaths in the Sonoma and Napa regions.

Standing Up for Their Rights

By 1850, American settlers began to move into Pomo lands. The US government sometimes forced Pomo people onto reservations to make way for these new settlers. Some Pomo found work on ranches, while others lived in temporary villages.

During this time, two settlers, Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone, treated many Pomo people very unfairly. They forced Pomo men and women to work in harsh conditions. The Pomo, tired of this mistreatment and seeking freedom, fought back, leading to the deaths of Kelsey and Stone.

In response, the US military sent soldiers to the area. This led to a tragic event in 1850 known as the Bloody Island Massacre. On an island in Clear Lake, soldiers killed between 60 and 100 Pomo people, mostly women and children.

Forced Moves and Resilience

Soon after the massacre, in 1851 and 1852, the US government created four reservations for the Pomo in California. Many Pomo were also forced to move during the "Marches to Round Valley" in 1856. White settlers, using force, demanded that Pomo people move to reservations. The reason given was to "protect their culture" by removing them from their ancestral lands.

Before European arrival, an estimated 3,000 Pomo lived around Clear Lake. After the many deaths from disease and conflicts, only about 400 Pomo remained. Despite these immense challenges, the Pomo people showed incredible strength and resilience.

From 1891 to 1935, artist Grace Hudson painted over 600 portraits, mostly of Pomo individuals living near Ukiah. Her paintings showed everyday Pomo life and helped preserve images of a culture that was rapidly changing.

Pomo Population and Languages

How Many Pomo People Are There Today?

In 1770, there were about 8,000 Pomo people. By 1851, the population was estimated to be between 3,500 and 5,000. The 1910 Census counted 1,200 Pomo. According to the 2010 United States Census, there are 10,308 Pomo people in the United States, with 8,578 living in California.

The Pomoan Languages

Pomo, also known as Pomoan, is a family of seven different languages. These languages are so distinct that speakers of one cannot easily understand speakers of another. They include Northern Pomo, Northeastern Pomo, Eastern Pomo, Southeastern Pomo, Central Pomo, Southern Pomo, and Kashaya.

After European-American settlement, the Pomoan languages became seriously endangered. Policies like the 1887 ban on teaching Native American languages sped up the shift to English. Today, about twelve Pomo language varieties are still spoken. Some, like xay tsnu spoken by the Elem Pomo, are being actively revived through community efforts.

Pomo Culture and Traditions

Pomo cultures are made up of many different groups that share a language family in Northern California. Originally, there were hundreds of independent Pomo communities.

Daily Life and Food

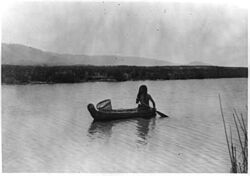

Like many other Native groups, the Pomo people relied on fishing, hunting, and gathering for their food. They ate salmon, wild greens, mushrooms, berries, grasshoppers, rabbits, rats, and squirrels. Acorns were the most important food in their diet. In Pomo communities, women typically gathered and prepared plant-based foods, while men were hunters and fishers.

Spiritual Beliefs and Ceremonies

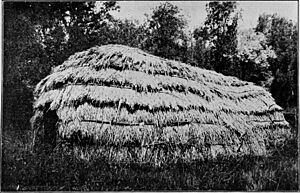

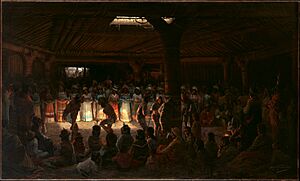

The Pomo people practiced shamanism, a spiritual tradition involving healers and the spirit world. One important form was the Kuksu religion, found in Central and Northern California. This religion included special dances, ceremonies, and an annual mourning ceremony. The Pomo believed in a spirit called Kuksu or Guksu, who lived in the south and came to heal illnesses. They also believed in spirits from six directions and Coyote as their ancestor and creator. Medicine men would dress up as Kuksu during ceremonies.

In 1872, the Ghost Dance was introduced to the Pomo and quickly spread. Later, the Bole Maru and Big Head cults also became part of Pomo spiritual practices. While some of these movements faded, Bole Maru continued to be practiced for many years.

Amazing Pomo Basket Weaving

Pomo baskets are famous around the world for their beauty, detailed techniques, fine weaving, and variety of shapes and uses. Pomo women made baskets for cooking, storing food, and religious ceremonies. Pomo men also made baskets for fishing traps, bird traps, and baby carriers.

The Art of Basket Making

Making these baskets required great skill and knowledge. Weavers had to collect and prepare materials like swamp canes, rye grass, willow shoots, and sedge roots. These materials were gathered throughout the seasons, then dried, cleaned, split, soaked, and sometimes dyed.

Pomo women often decorated baskets with the bright red feathers of the pileated woodpecker, making the surface smooth and colorful. They also added beads and pendants made from polished abalone shells. Some gift baskets took months or even years to create.

Weavers used three main techniques: plaiting, coiling, and twining. The designs woven into the baskets often had special cultural meanings. For example, the Dau, or "Spirit Door," was a small opening in the stitching. It was believed to allow good spirits to enter the basket and release other spirits.

Baskets in Daily Life and Trade

Baskets were essential for daily Pomo life. Babies were cradled in baskets. Acorns were harvested in large conical baskets. Food was stored, cooked, and served in baskets, some of which were even watertight. There were even large "baskets" used as boats to carry women across rivers.

After European contact, a market for authentic Pomo baskets grew from about 1876 to the 1930s. Pomo weavers like William Ralganal Benson and his wife, Mary Knight Benson, were among the first California Native Americans to support themselves by making and selling baskets.

This period was a turning point for the Pomo. Even though they had lost much of their land, basket weaving became a way to earn money and keep their traditions alive. Grandmothers and daughters taught others, helping to revive the art of basket weaving. The demand for these beautiful baskets grew across California.

In addition to baskets, the Pomo also made intricate jewelry from abalone and clamshells. These pieces were worn during celebrations and rituals, and given as gifts.

Basket Weaving Today

Pomo basket weaving is still highly valued today. It is appreciated by the Pomo people, art lovers, and museums. The Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, a tribe of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo, continue to honor this tradition.

One famous Pomo master weaver is Julia F. Parker. She learned from other master weavers like Lucy Telles and Elsie Allen. Julia has demonstrated her skills at museums and even presented her baskets to Queen Elizabeth II.

Weavers carefully gather materials like sedge root, willow shoots, and redbud shoots. They gather these materials with respect, seeing them as living things that offer themselves for something useful and beautiful. The process of dyeing some roots can take months.

Today, new Pomo baskets can sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars. Historical baskets can be worth much more. The time, skill, and rare materials needed to create these artistic pieces make them very valuable.

Pomo Communities Today

Federally Recognized Pomo Tribes

Today, many Pomo tribes are "federally recognized." This means they have a special relationship with the United States government. They are considered "domestic dependent nations," which gives them some self-governance within their states, including California.

Federally recognized Pomo tribes are located in Sonoma, Lake, and Mendocino counties. They include:

- Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians of the Big Valley Rancheria

- Cloverdale Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians of California

- Dry Creek Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Elem Indian Colony of Pomo Indians of the Sulphur Bank Rancheria

- Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria (a tribe of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo)

- Guidiville Rancheria of California

- Habematolel Pomo of Upper Lake

- Hopland Band of Pomo Indians of the Hopland Rancheria

- Kashia Band of Pomo Indians of the Stewarts Point Rancheria

- Koi Nation of the Lower Lake Rancheria

- Lytton Rancheria of California

- Manchester Band of Pomo Indians of the Manchester Rancheria

- Middletown Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Pinoleville Pomo Nation

- Potter Valley Tribe

- Redwood Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Robinson Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Round Valley Indian Tribes of the Round Valley Reservation (a confederation of several tribes, including Pomo)

- Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians of California

- Sherwood Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

Challenges and Restoring Rights

Many Pomo tribes were affected by the California Rancheria Termination Acts. During this time, some tribes lost their lands and their status as federally recognized tribes. This meant they also lost access to federal services. However, in 1983, a court decision in Hardwick v. United States helped restore the status of 17 California rancherias, including some Pomo tribes.

Historical Pomo Groups

The Pomo people were traditionally divided into several large groups, each speaking its own language. While these groups did not have one single government, they shared cultural traits and were recognized by those who lived among them:

- Kashia (Southwestern Pomo)

- Southern Pomo

- Central Pomo

- Northern Pomo

- Tceefoka (Northeastern or Salt Pomo)

- Eastern Pomo (Clear Lake Pomo), spoke Bahtssal

- Elem Pomo (Southeastern Pomo)

Here is a list of historical Pomo villages and tribes:

- Balló Kaì Pomo, "Oat Valley People" (Potter Valley, Mendocino County)

- Batemdikáyi

- Búldam Pomo (Rio Grande or Big River)

- Chawishek

- Choam Chadila Pomo (Capello)

- Chwachamajù

- Dápishul Pomo (Redwood Canyon)

- Eastern People (Clear Lake about Lakeport)

- Erío (mouth of Russian River)

- Erússi (Fort Ross)

- Gallinoméro (better Kainameah, Kianamaras or Licatiuts) (Russian River Valley below Cloverdale and in Dry Creek Valley)

- Gualála (better Ahkhawalalee) (northwest corner of Sonoma County)

- Kabinapek (western part of Clear Lake basin)

- Kaimé (above Healdsburg)

- Kai Pomo (between Eel River and South Fork)

- Kastel Pomo (between Eel River and South Fork)

- Kato Pomo, "Lake People" (Clear Lake)

- Komácho (Anderson and Rancheria Valleys)

- Kulá Kai Pomo (Sherwood Valley)

- Kulanapo (Clear Lake)

- Láma (Russian River Valley)

- Misálamag[-u]n or Musakak[-u]n (above Healdsburg)

- Mitoám Kai Pomo, "Wooded Valley People" (Little Lake)

- Poam Pomo

- Senel (Russian River Valley)

- Shódo Kaí Pomo (Coyote Valley)

- Síako (Russian River Valley)

- Sokóa (Russian River Valley)

- Yokáya (or Ukiah) Pomo, "Lower Valley People" (Ukiah City)

- Yusâl (or Kámalel) Pomo, "Ocean People" (on coast and along Usal Creek)

Famous Pomo People

- William Ralganal Benson (1862–1937)

- Mary Knight Benson (1877–1930)

- Elmer Busch (1890–1949)

- Laura Somersal (1892–1990), basket weaver

- Elsie Allen (1899–1990)

- Essie Pinola Parrish (1903–1979)

- Mabel McKay (1907–1993)

- Julia F. Parker (born 1928)

- Luwana Quitiquit (1941–2010), basket weaver who created a program to revive the craft

- Susan Billy (born 1951), basket weaver

- Chuck Billy (born 1962), singer of the metal band Testament

- Danielle Forward, software engineer and Indigenous activist

- Franklin Dollar, physicist

See Also

In Spanish: Pomo (etnia) para niños

In Spanish: Pomo (etnia) para niños

- Point Arena Rancheria Roundhouse, also known as "Manchester Rancheria Roundhouse", listed on the National Register of Historic Places

- Frog Woman Rock

- Lake Mendocino

- Santa Rosa Creek

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |